October 2019

What, you may ask, is a cenote? Since it’s an object of primary interest to us in this post, allow me to explain.

What, you may ask, is a cenote? Since it’s an object of primary interest to us in this post, allow me to explain.

Here’s the dope from the Wikipedia page (here):

Cenotes are surface connections to subterranean water bodies. While the best-known cenotes are large open water pools measuring tens of meters in diameter, such as those at Chichén Itzá in Mexico, the greatest number of cenotes are smaller sheltered sites and do not necessarily have any surface exposed water. There are over 6000 different cenotes in the Yucatán Peninsula in Mexico alone.

The term cenote has also been used to describe similar karst features in other countries such as Cuba and Australia, in addition to the more generic term of sinkholes.

Cenote water is often very clear, as the water comes from rain water filtering slowly through the ground, and therefore contains very little suspended particulate matter. The groundwater flow rate within a cenote may be very slow. In many cases, cenotes are areas where sections of cave roof have collapsed revealing an underlying cave system, and the water flow rates may be much faster: up to 10 kilometers (6 mi) per day.

Cenotes around the world attract cavern and cave divers who have documented extensive flooded cave systems through them, some of which have been explored for lengths of 340 km (210 mi) or more.

The word itself is from the Yucatecan Maya word ts’onot, used for any site at which groundwater is available.

There are thousands of cenotes in the Yucatan Peninsula. For the Mayans they were sacred sites as well as sources of fresh water. Important Mayan sites such as Chichen Itza included cenotes within the boundaries of the city. So naturally having some contact with cenotes had inevitably to form part of my experience during my two-week trip through the Yucatan. I saw my first cenote at Dzibilchaltun, where the water is at ground level. After a couple days sightseeing in Merida I did a Google search on cenotes in the Merida area and came up with an intriguing site describing the Cenote de San Ignacio. I asked the person at the hotel front desk, a native of Merida, if he’d ever heard of it. To my great surprise he hadn’t. Many cenotes are in out-of-the-way places difficult of access and without any facilities. The Cenote de San Ignacio is right off the main highway to Campeche and is set up as a recreational site with a full-on restaurant. The presence of creature comforts decided me then and there to make it the cenote of choice for a visit.

The Cenote is in the small town of Chocholá, a very manageable 40km south of Merida. The fact that it sits right off Federal Highway 180 — the main route to Campeche — makes it all the more appealing. There’s no question of bumping and grinding down a dirt road for 10km to reach a cenote that has empty beer bottles spread around its edges. I have no idea who developed the Cenote but my hat is off to them for a fantastic job of it. The organizational website (here) is one of the best websites I’ve encountered for a tourist spot in Yucatan. It even includes pages in English, which is a rarity and clearly aimed at appealing to an international crowd.

When you drive into Chocholá there’s no huge billboard announcing the Cenote. I found it easily because of the map on the website, but it’s an unassuming presence in the town, which looks exactly like any other Mexican town of its size. Even the entrance to the Cenote is unremarkable. Once you go through the entryway and enter the facility, however, it becomes immediately clear that this place is special.

I don’t have a lot of pics from the Cenote, but there’s a good gallery on the organizational website so I’ll throw out mine and steer your attention to those on the Cenote’s website for more visuals:

I’m not a water baby and had no intention of swimming in the cenote, which is of course all the rage when you go to one. My bead was on the restaurant (exactly as it was at Sotuta de Peon) which features a wide array of Yucatecan cuisine. The facility is not very large but it’s quite pleasant. As you see in the pics there are several palapa huts for dining and hanging out. There’s a swimming pool, as well, which seemed as popular with swimmers as the cenote itself. It was a hot day when I went — as are all days in Yucatan in September, to be honest — but the shade of the huts rendered the sun a much milder manifestation and the breeze kept things cooled off another few degrees so I was comfortable the whole time I was there.

As Wikipedia mentions, not all cenotes have a window above them: “… smaller sheltered sites and do not necessarily have any surface exposed water.” As you can see in the last two pics the Cenote de San Ignacio is one of the underground ones. The stairwell down to the cenote had a decidedly Plutonian look to it but I plucked up my bravery and descended. It was stuffy and humid. There were lightbulbs (bare, of course) strategically placed around the site to illuminate the cenote, which would otherwise be in pitch darkness because it’s subterranean. There were a few families cavorting in the shallow water, but after the drive from Merida it only took about five minutes down below for my stomach to urge me back into the daylight, headed for the restaurant. That’s where the real fun began.

The restaurant is a large, open-air building fitted with a typical Maya roof — timber structure covered with palm leaves. Here’s a look into the rafters:

Curiously enough such roofs are spendy things to build — according to information I had from one local informant. They’re labor intensive and cost much more than a conventional modern roof. From my perspective as a customer I thought the expense well worth it, since sitting in an open air building with a roof like the ones the Mayas themselves made added a nice feel to the place.

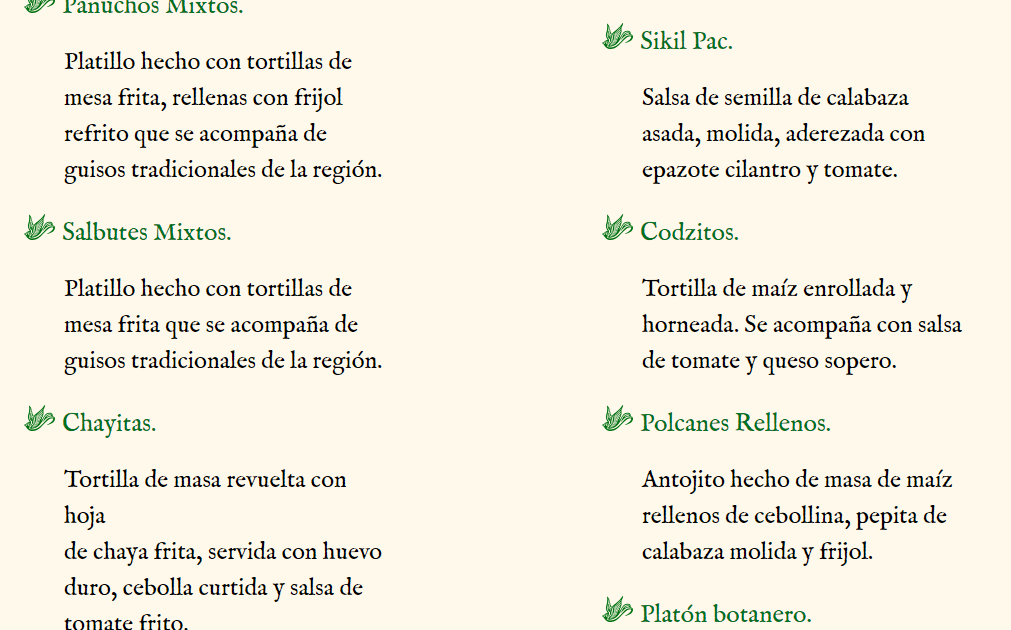

But the food was what drew me because I’d gone through the menu on the organizational website. Here’s what I found for “entradas” (entrees):

Even if you speak Spanish the names of the dishes may well be unfamiliar since we’re not in the world of tacos, enchiladas or burritos that we know from the Tex-Mex cuisine common in the States. Yucatecan food is quite different and some of the names of dishes are Mayan, not Spanish. So let’s have a closer look at the dishes in the screenshot and see what’s up.

Panuchos have their own Wikipedia page so let me quote:

Panucho is a Mexican food specialty from the Yucatán made with a refried tortilla that is stuffed with refried black beans and topped with chopped cabbage, pulled chicken or turkey, tomato, pickled red onion, avocado, and pickled jalapeño pepper.

I would add that panuchos can also be topped with pit-roasted pork called cochinita pibil which is a major taste treat.

Sikil pac is obviously Mayan, not Spanish. It’s Mayan guacamole, made with pumpkin seeds instead of avocado. It’s an accompaniment just like guacamole and you’ll usually find a blob of it on the plate along with whatever else you’ve ordered. It’s an unusual and pleasant flavor that I grew to like a lot during my two weeks in the Yucatan. Pumpkin seeds are called pepitas in Spanish, but I’ve never come across the dish called by a recognizable Spanish name such as salsa de pepitas so just remember the Mayan name and you’re golden.

Salbutes are the Mayan answer to tostadas. Here’s a description from their Wikipedia page:

A salbut is a puffed deep fried tortilla that is topped with lettuce, sliced avocado, pulled chicken or turkey, tomato and pickled red onion. Salbutes originate from the Yucatán peninsula and are a staple in Belize.

Codzitos are one dish I never tried during my trip, not for lack of interest on my part but because they weren’t easy to come by and there were too many other things to try when I was at a restaurant that offered them. Here’s the skinny on them from tasteatlas.com:

Codzitos is a Yucatecan dish consisting of fried tortilla rolls. The name of the dish is derived from the Mayan word koots (codz), meaning to roll. In order to prepare it, stale tortillas are stuffed with shredded meat (usually pork or chicken) and cheese, then fried.

Originally, codzitos were invented as a way to use up leftover tortillas. When served, this appetizer is traditionally topped with homemade tomato salsa, and it can be garnished with grated cheese and cilantro.

Chayitas require a bit more explanation because the defining ingredient, chaya, is a Yucatecan thing not common elsewhere in Mexico. I was completely unfamiliar with it and first encountered it as deep fried thingeys on a plate of Yucatecan traditional foods. It’s kind of like Japanese seaweed in texture. Personally I don’t find it a wow moment, but hey, you go with the flow. Here’s some info from the website alinteriordelestado.com:

La planta conocida comúnmente como Chaya, es endémica de la Península de Yucatán. El grupo mesoamericano maya le llamaba chay, su nomenclatura científica es Cnidoscolus aconitifolius. Y desde entonces ha sido elemento sustancial de la dieta del habitante de esta tierra, y día con día investigaciones de rigurosidad científica le aducen propiedades medicinales importantes que abonan a su importancia, aconsejable en la ingesta diaria.

Esta simpática planta, cuya creencia popular reza que sólo provoca comezón al tacto a quien no pertenece a la raza maya, puede figurar en el desayuno, en el almuerzo o en la cena; en el desayuno, se puede preparar con huevo, en una comida formal es protagonista de empanadas, tamales y también sus hojas pueden ponérsele al tradicional Puchero. También se puede disfrutar en una mitigante agua fresca, con limón.

[The plant commonly known as “chaya” is endemic to the Yucatan Peninsula. The Mayans called it “chay” and its botanical name is Cnidoscolus aconitifolius. It’s long been an important regional footstuff and scientific investigations continually discover new medicinal properties that recommend it as a daily menu item.

This useful plant, which in popular belief only causes skin irritation when touched by non-Mayans, can be used for breakfast, lunch or dinner; for breakfast it can be prepared with eggs, in a formal dinner it can figure in empanadas, tamales or in traditional puchero. It can also be used in a fresh juice drink with lime.]

Polcanes are tasty tidbits on the order of tostadas. Here’s the word once again from alinteriordelestado.com:

El popular “polcán” está hecho de masa de maíz y relleno de cebollina, pepita de calabaza molida e “ibes” (un frijol blanco particular de nuestra región), está combinación de ingredientes del relleno se le conoce como “toksel”. Por cierto, “Polcan” proviene de la lengua maya, “Pol” que significa cabeza y “can” serpiente, y crea el nombre “polcán” cabeza de serpiente.

[The popular “polcan” is made with corn masa filled with onion, ground pumpkin seed and “ibes” (a whilte bean special to our region), this combination of ingredients as a filling is called “toksel.” To be sure, “polcan” comes from the Mayan language. “Pol” means “head” and “can” snake, which gives the name “polcan,” snakehead.]

I suppose if you’re Mayan the idea of eating snakeheads has its place in the scheme of things. I’m good with thinking of them as a Mayan variation of tostadas. 🙂

To the list above I’ll add one more common Yucatecan dish: papadzules. I had them several times and like them a lot. They’re corn tortillas filled with chopped hardboiled eggs and covered in a sauce made with ground pumpkin seeds. Yummy!

At the bottom of the menu screenshot you see the name “Platon botanero.” It’s a platter made up of different Yucatecan specialties, so let’s take a closer look:

When I came across this option it took about 2 seconds to decide that was the thing for me. And oh boy was it a good choice. Here’s a pic of what came out of the kitchen:

And yes, it tasted as good as it looks. 🙂

There’s one other thing I’ll mention about Yucatecan food. It’s a calorie fiesta as well as a party for your taste buds. After two weeks of chowing down on such delectable things as you see in the pic above I headed home with the firm resolution to eat nothing but salad for two weeks so that my middle could regain is previously svelte proportions. I did no scientific calculations concerning how much my waistline increased after each meal of Yucatecan delicacies, but the cumulative effect was noticeable after two weeks. So just be aware, it’s not a slimming diet by any stretch of the imagination.

I’m still amazed that my friend from Merida had never heard of the Cenote de San Ignacio. If ever you happen to find yourself in Merida and want a lovely day trip heading south, I’d recommend putting the Cenote on your bucket list. The drive is pleasant and you can easily while away a morning, an afternoon or an entire day at the Cenote. I’m here to sing its praises and encourage more expat tourists to discover its charms. Two thumbs up!