November 2019

If you do due diligence in your travel planning for a jaunt around the Yucatan Peninsula, you’ll come across Izamal as one of the biggies. It’s known as the “Yellow City” because most of the buildings are painted in the same shade of yellow. This isn’t something that dates back very far, however. It was a response to the visit by the Pope in 1993. There’s some scuttlebutt afoot that it also has something to do with Izamal being in Mayan times a pilgrimage place for worship of the sun god. That bit of news and a quarter will get you half a cup of coffee, but there it is.

If you do due diligence in your travel planning for a jaunt around the Yucatan Peninsula, you’ll come across Izamal as one of the biggies. It’s known as the “Yellow City” because most of the buildings are painted in the same shade of yellow. This isn’t something that dates back very far, however. It was a response to the visit by the Pope in 1993. There’s some scuttlebutt afoot that it also has something to do with Izamal being in Mayan times a pilgrimage place for worship of the sun god. That bit of news and a quarter will get you half a cup of coffee, but there it is.

The website Earth Trippers in its posting entitled “The Magic of Izamal, Mexico’s Yellow City” (here) gives us the skinny:

In 1993, they announced that Pope John Paul II would visit Izamal that August. He would perform a mass as part of his tour of Mexico. The town knew it had to spruce up the place.

Someone had the brilliant marketing idea to paint all the houses, including the convent, the same color. Why yellow? The sun, the corn, and then of course the Vatican flag – it has a big band of bright yellow on the left side.

Well, the papal visit now lies nearly 20 years in the past and the yellowness of Izamal has a less luminous glow to it than it no doubt did in 1993.

The Wikipedia page on Izamal informs us about the city’s historical aspect:

After the Spanish conquest of Yucatán in the 16th century a Spanish colonial city was founded atop the existing Maya one; however it was decided that it would take a prohibitively large amount of work to level these two huge structures and so the Spanish contented themselves with placing a small Christian temple atop the great pyramid and building a large Franciscan Monastery atop the acropolis. It was named after San Antonio de Padua. Completed in 1561, the open atrium of the Monastery is still today second in size only to that at the Vatican. Most of the cut stone from the Pre-Columbian city was reused to build the Spanish churches, monastery, and surrounding buildings.

Izamal was the first chair of the Bishops of Yucatán before they were moved to Mérida. The fourth Bishop of Yucatán, Diego de Landa lived here.

There is no mention that Diego de Landa is the bishop infamous for burning hundreds of Mayan codexes. In other words, he belongs in the same class as Torquemada of Inquisition fame. He represents a destructive and culturally toxic form of humanity still very much with us, as we see with regrettable regularity as we follow the news emanating from Washington, D.C. Why the Wikipedia article neglects to mention the facts I can’t say. Obstruction of justice? Executive privilege? Who knows. If you want the whole sordid story you can find it here. That de Landa thought the better of it later and cobbled together what he hoped would be a substitute for the hundreds of volumes he consigned to the flames fails to improve my opinion of him. He destroyed irreplaceable cultural artefacts. Bugger him and everyone like him, be they Catholic bishops or Nazis throwing books onto bonfires.

Izamal is a petit place, nothing grandiose about it, which is one of the reasons I chose to spend a couple days there. When I drove into town and wended my way through the streets to the hotel I saw that once you’ve seen one historical Mexican town, you’ve basically seen them all, no matter what color they are. Streets lined with houses of a single storey with a door in the middle are a basic item, the urban equivalent of socks or underwear. Just as you wouldn’t think of leaving the house without your underwear on, so no town in Mexico will be without its streets lined with single-storey houses with a door in the middle. They just gotta be there, people need someplace to live. And if you’ve got a basic pattern from your colonial overlords who completely lack imagination and simply want to reproduce what they know from the Old Country, you wind up with this:

All well and good. The hotel I chose turned out to be the most fortunate choice possible because it sits on the edge of town with a view out over some relatively open countryside. The sight of green always lifts my heart and I feel I know Izamal even more because I’ve seen its natural setting in addition to its architectural sights. The major complaint I have with the Spanish approach to town planning is that it effectively eliminates the presence of Nature. Look at the above photo. In a place where things grow so luxuriously that you can fairly see them increase in size while you stand there gawking at them, does it make sense to reduce the landscape to stucco, stone and asphalt? I think not. Call me a landscape revanchist if you will, but that’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

So, our Yellow City has both significant colonial and Mayan elements. Izamal before becoming a colonial bishopric was an important Mayan center. Calling once again on my go-to info source for Mayan sites, themayanruinswebsite.com, I quote this info on Izamal:

Izamal’s settlement reaches back to the Middle Pre-Classic (700-250 B.C.), and most of its construction was accomplished during its heyday in the Late Pre-Classic through the Early Classic (300 B.C.-600 A.D.). It began a slow decline after this though it did experience a small spurt of activity in the Terminal Classic (900-1100 A.D). It is thought that at this time Izamal came under the influence of Chichen Itza. Izamal continued to be a pilgrimage destination into the Spanish Colonial Period.

Izamal was first mentioned in the Spanish chronicles, but the first full report was done by those intrepid explorers John Lloyd Stephens and Frederick Catherwood in the 1840’s. Catherwood, a gifted artist, drew a portrait of the famous face of the Sun god, Kinich Ahau, that once adorned the side of a structure. It has since disappeared and this drawing remains our only record. Unfortunately, much of the site has been quarried for building materials over the centuries, while other parts have been completely built over. There is ongoing excavation and restoration projects throughout the site.

The Spanish invaders recognized the importance of the ruins to the indigenous Maya and erected a massive religious complex known as the Convent of San Antonio de Padua within its ceremonial center in 1549 A.D. This Catholic religious site was visited by Pope John Paul II in 1993, and has since become a modern pilgrimage site for Mexican Catholics.

Robbing Peter to pay Paul in the architectural dimension, it appears — some might call it “vandalism,” but let’s be generous and call it “repurposing.” Shall we? Good. On we go then to the pics.

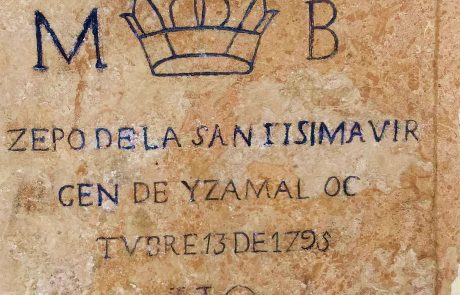

There’s only one main sightseeing gig in town on the colonial side of the ledger: the Convento de San Antonio de Padua. The pic sequence above takes the Convent as its focus. To be perfectly honest, it looks better from a distance than close up IMHO. From a distance and framed in a filigree of leaves it has both charm and a certain grandeur. Up close it becomes — to put it blankly — sinister. The architecture is graceless and crude. Looking through the passageways made me feel that I was in a prison compound, not a convent. The church has some admirable woodcarving on display and the altar is impressive in a modest sort of way, but the overall impression the convent gives is sinister and gave me major creeps. As I looked at the large but hamfisted structure I thought of all the cruelty that undoubtedly took place in that space over the centuries. It’s also rather decrepit at this juncture. The enormous plaza in front of the convent, touted to be the second largest in the world after that of the Vatican, looks like a vacant lot. After about 15 minutes I just wanted out of the place. On the way back to the main square I walked past a part of the plaza that sported the lovely wildflowers you see in the last pic. For my part I’d be quite happy if that was the only thing I’d seen there.

I went to Izamal after spending four days in the Puuc region seeing Uxmal and the Ruta Puuc sites (Labna and Sayil primarily). The Mayan ruins on offer in Izamal can’t compare either in scope or quality. There is a pyramid in Izamal, but it’s truly a ruin and I didn’t feel the need to see it with visions of the Governor’s Palace at Uxmal still dancing in my head. So let me just throw out the pics and let you draw your own conclusions:

Yeah, I know. Kapok trees again. Somebody’s got an obsession … Well, if I see some stone blocks piled on top of each other standing right beside a lovely large tree with a broad, leafy canopy, I’ll pick the tree 10 times out of 10. My bad. If you get tingles up the spine from the sight of the stone blocks, rock on. It takes all kinds, right?

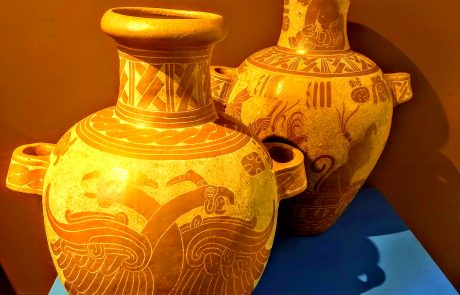

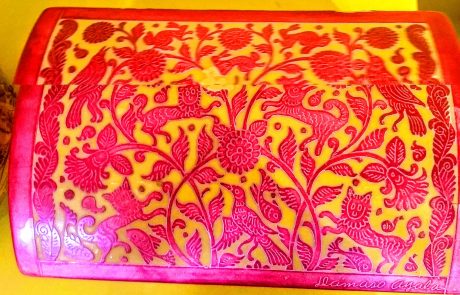

My research on Izamal failed to turn up something I’d have been very sorry to miss: the Centro Cultural y Artesanal de Izamal (The Izamal Cultural and Handicraft Museum). I came across it as I walked around the area of the main town square and immediately realized I’d be a fool not to check it out. It goes well beyond collecting local handicrafts — it’s actually a contemporary art gallery. It’s a lovely facility and the collection it has is fantastic. I’ll let the pics do the talking:

The artists represented come from all over Mexico, not just from Izamal. Given the enormous range of media represented, I think it must count as one of the better collections of its kind in the region. So dear reader, if you find yourself in Izamal pressed for time and forced to choose between rambling through the Convento de San Antonio de Padua or spending time in the Museum, choose the latter. The things you see in the latter will stick in your mind much longer than images of the former, I do believe. That certainly proved to be the case for me.

Izamal was my swan song for the two-week sojourn I had in the Yucatan. I spent another two days in the region, in Valladolid, which I thought would serve me as a base for trips to see Ek Balam and perhaps even Chichen Itza. But after nearly two weeks of hard-core touristing I was spent, especially because of the climate, which sucks the energy out of you like a shop vac with a turbo motor on it. I contented myself in Valladolid with staying in the green haven of my hotel, which turned out to be as lucky a choice as the one in Izamal was. One drive through the downtown of Valladolid was enough to put me off the idea of repeating the experience — traffic was a snarl, people were running back and forth across the streets, and I didn’t want to tempt the Fates to see if my auto insurance was all it was cracked up to be. I was perfectly happy playing quietly in my room at the hotel, sorting through pics and organizing my thoughts for these posts on the trip. After a few days pleasantly spent in that occupation it was time to jump back into the trusty Chevy and head to the airport in Cancun for the trip back to the USA.

Izamal was a good end point, actually. It brought the colonial past back into focus for me after spending nearly two weeks in the pre-Hispanic world. Say what you will, the Mayan sites on the Yucatan peninsula represent a world that is remote enough from us now to be mythical. We know so little about the civilization, really, compared to what we know about the Conquista and the colonial period. My time in Izamal showed me that I’d done exactly the right thing to concentrate on the Mayan side of things and give short shrift to the colonial element. The Mayan architecture I saw was astonishing and wonderful. The colonial architecture I saw was little more than a reminder that the Conquista happened and bad things ensued thereafter. But the Museum collection in Izamal showed me how the life of Mexican people is a rich composite of all those things — the indigenous, the Spanish, the colonial, the modern Latin American — and I’m glad I ended my trip with that baseline brought squarely to my attention.

So all in all the trip was a great success. If I were writing a travel guide I’d recommend the Yucatan as one of the treasure regions of Mexico. It’s that good. I’ll hold the memories made during my travels there in fond remembrance.