November 2019

Following hard on the heels of the last post on Labna comes this one on Sayil, just a few kilometers down the road from Labna. Though they are a stone’s throw from each other on the ground, they’re completely different and if you’re in the area both sites should be on your bucket list. Don’t think for a moment that if you’ve seen one Mayan archeological site you’ve seen them all, not even if they’re only a few kilometers apart. Labna and Sayil are as different as chalk and cheese and I’m very glad I devoted ample time to each site. Each provided its own set of experiences and pleasures. With Labna handled in the last post it’s time to turn our attention to Sayil. Let’s get going.

Following hard on the heels of the last post on Labna comes this one on Sayil, just a few kilometers down the road from Labna. Though they are a stone’s throw from each other on the ground, they’re completely different and if you’re in the area both sites should be on your bucket list. Don’t think for a moment that if you’ve seen one Mayan archeological site you’ve seen them all, not even if they’re only a few kilometers apart. Labna and Sayil are as different as chalk and cheese and I’m very glad I devoted ample time to each site. Each provided its own set of experiences and pleasures. With Labna handled in the last post it’s time to turn our attention to Sayil. Let’s get going.

From my go-to site for Mayan ruins, themayanruinswebsite.com, comes this information on Sayil:

Sayil is a Classic Maya site (600-900 A.D), that reached its greatest extent in the 9th-10th century. It was part of a group of sites that stretched along the base of the Puuc Hills and shared in the same time frame and architectural style. They include Kabah, Labna, Uxmal and Oxkintok, though a few of these have a much earlier history.

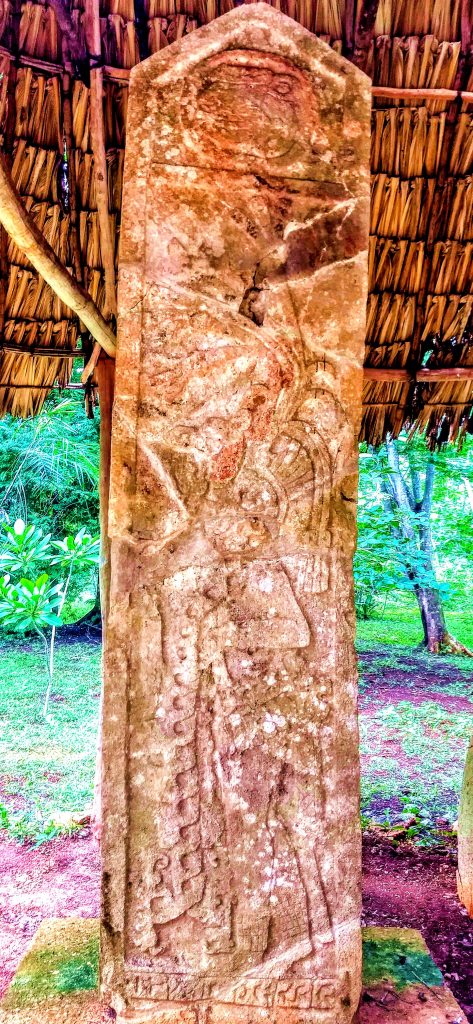

While a few stelae have been recovered at the site, none have been able to provide definitive information on its rulers, though one provides a date of 810 A.D.. Artifacts recovered from the site reveal a strong trade relationship with the Peten region in Guatemala. The site, along with most of the other associated Puuc sites, was abandoned around 1000 A.D.

Sayil was rediscovered by those intrepid explorers John Lloyd Stevens and Fredrick Catherwood in the 1840’s. Exploration, excavation and restoration work has been carried out for most of the past century, with the University of New Mexico undertaking extensive investigations in the 1980’s-90’s.

From the Wikipedia page on the site comes this additional information:

Sayil first was settled circa AD 800, in the Late Classic Period, possibly by small Chontal warrior groups.[7] The city reached its greatest extent c. 900, when it covered an area of approximately 5 km² and had a population of perhaps 10,000 in the city itself with an additional 5,000–7,000 living in the surrounding area.[1]

At the height of the city’s occupation, the population reached the limits of the agricultural carrying capacity of the land, with crops grown in gardens and fields among the residential complexes and irrigated from artificial cisterns built to store water from the seasonal rains, and more distant fields in neighbouring valleys, probably were cultivated. Additional agricultural produce probably was supplied from nearby satellite sites.

Sayil began to decline c. 950 and the city was abandoned by c, AD 1000, a pattern of rapid growth and decline that probably was typical of the Puuc region.

Archaeologists have surveyed 2.4 km² of the site, revealing an average structural density of 220 structures/km². Population estimates have been produced based on a count of structures, giving a result of 8,000–10,000 spread over an area of approximately 3.5 km². Population estimates based on a count of subterranean storage chambers known as chultuns produce a figure of 5,000–10,000. Both estimates refer to the maximum population in the Terminal Classic.[10]

Political, economic, social, and religious leadership at Sayil appears to have been distinct and relatively decentralised. Economic rank has been analysed based on architectural scale, while political leadership was determined on the basis of the distribution of so-called altars, tall cylindrical stone features with elite associations. The distribution of religious leadership was determined by the distribution of ceramic incense vessels and social leadership by the presence of rare ceramics obtained via intercommunity social alliances.

Smaller sites around Sayil, such as Sodzil, Xcavil de Yaxche, and Xkanabi, may have been tributary communities.

Since Sayil is only 5km from Labna on the way back to Uxmal, it figured as the second site of the day I spent doing the Ruta Puuc. The point I made above about the two sites being very different hits you as you enter the Sayil site. It’s more developed and there’s a stela standing near the entrance hut. Unfortunately it’s so eroded you can barely make out the figures, so it’s a bit disappointing, but still, a stela is a stela, so let us not cavil:

Since it’s unlikely that I’ll ever see the more impressive stelae at Copan before I kick the bucket, I took my luck for good seeing this stela at Sayil. At least I can now say I’ve been in the presence of such a creature, and that’s worth something to anybody who cares about Mayan art as I do.

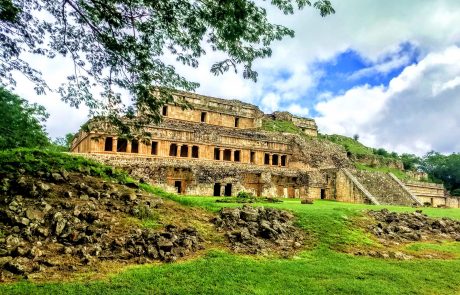

The main difference between Labna and Sayil is openness and the lack of it. Labna stands out in the open exposed before God and everybody. Sayil is exactly the opposite. You wander through the forest on (often muddy) paths to reach various groupings of buildings. There is only one place where a broad vista greets the eye, and that place is the Palace. Since the open ground around the Palace is specific to that building it struck me as the Mayan equivalent of an English country house — say, Chatsworth. There the Palace sits, the largest building of any I saw at Sayil, with a lovely green open space around it keeping the encircling jungle at bay. That impression overwhelmed me as I caught sight of the building through the branches and leaves of a kapok tree growing on the path leading to it. In my mind I flipped from Sayil sunk in the jungles of the Yucatan to Sayil-on-Thames, the seat of the Dukes of Something-or-Other (maybe Ek Poop Balam or something equally outlandish), sat here in the middle of nowhere to remind us of the checkered history of the landed aristocracy, since as we all know the dukedom went extinct and the stories about the last inhabitants of the ducal seat leave one in no doubt about the wages of aristocratic decline. Here are the pics:

As you can see it’s quite a handsome spot and the kapok tree embellishes the basic item quite effectively as you approach it. I have several pictures of the kapok trees (Ceiba pentandra, called “ceiba” in Spanish) you pass as you move along the paths through the site. They were new to me on my arrival in the Yucatan and we quickly became BFFs. The first pic gives the kapok tree its own due, but the second pic shows just how much of a run for their money it gives to the oaks of Chatsworth. I can’t imagine a prettier picture of an English country house than the view of the Sayil Palace through the kapok filigree as it shows in the second pic.

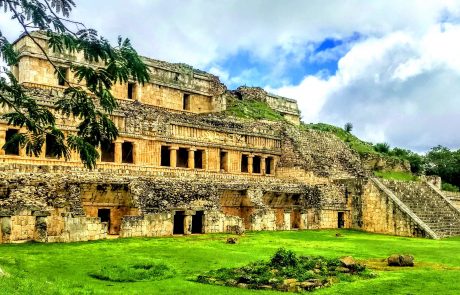

As for the Palace itself, it’s by far the most impressive building of the entire site and rivals — indeed, one may say surpasses — anything to be seen at Labna, including the famous arch. The thing that astonished me initially about the Sayil Palace is its size — it’s HUGE. Maybe not as huge as the Temple of the Magician at Uxmal, but hey, this isn’t Uxmal, it’s Sayil, stuck out in the middle of nowhere. So after indulging my romantic notion of Sayil-on-Thames with its extinct dukes I snapped back to reality and started to take in the structure and detail of the Palace. Here are some pics to get us going:

This structure — calling it a “palace” is perhaps no more than a flight of fancy, it could as well have been the Court House or the Mall of the Mayas — has no parallel at Labna. The buildings at Labna are much more horizontal than vertical and the decorative schemes are not so elaborate. It’s interesting to me to speculate about the causes of these differences. Sayil is closer to Uxmal, true, but only by 5km, which is not much. Could there have perhaps been dynastic or ruling family associations between the folks at Sayil and those at Uxmal? Who knows. Something was going on, clearly, because the differences between Labna and Sayil are too great to be simply a matter of chance. Since I’m a know-nothing tourist and free to confabulate my own origin myths, I’m going to stick with the idea I had about the Dukes of Ek Poop Balam. 🙂

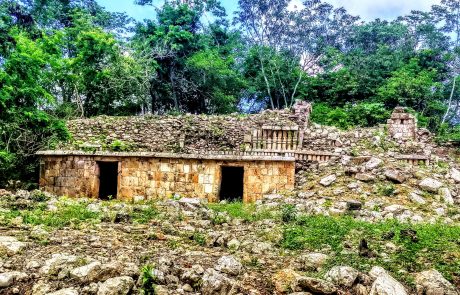

The excavated area at Sayil is much larger than the area of Labna, but I say that keenly aware that most of any Mayan site you visit still lies buried under the jungle floor. Perhaps there’s just been more clearing away at Sayil. Whatever the case, there’s a lot of walking to be done at Sayil, unlike Labna where there are only two architectural groups separated by a tiny bit of sacbe. At Sayil you have to walk through the forest to see the various groups. To be perfectly transparent, none of the building groups holds a candle to the Palace. It was lovely to walk through the forest and look at the plants, but if I had been pitched on the edge of my seat expecting to see buildings as impressive as the Palace at the other portions of the site, I’d have been deeply disappointed. Fortunately such was not my expectation. I didn’t know what I’d find. The major fun for me after seeing the Palace was walking through the forest and looking at the trees and plants. It’s lovely to get up close and personal with the natural environment in a way you can only do by being on foot in the middle of it. So let me put up the pics of the rest of the walk here:

The first and second pics show how lovely the forest is with its tall and handsome trees. After walking through such loveliness it was a bit anticlamactic to come across another example of the cockscomb building found at Labna. Call me picky but it seems an unimaginative approach to architecture. Just saying. Anyhoo, you needn’t stay with it long — I certainly didn’t — before continuing on the pathway to the next group of structures.

What I found at the last group I visited seemed to sum up the reality element with great force. When you look at the Palace at Sayil in all its Chatsworth elegance, it’s easy to forget that when it was found it was buried in jungle detritus and took years of work to achieve its present state of restoration. The last pic in the group shows what things probably looked like at the Palace before all that work had been done. What can this lump of masonry buried in the jungle have once been? What can it have looked like when it was brand new? We’ll never know the true story, I think, since there’s nothing to go by as far as the historical record goes. That’s the big difference between places like Sayil and places like Chatsworth, which has a proper archive with all kinds of things archeologists and art historians find titillating. e.g. architectural drawings, letters, account books and the like. None of that at Sayil, of course. I’m always amazed that the archeologists do as good a job as they do putting these heaps of stones back on top of one another in a way that yields a building that looks quite authentic to me.

A final word on Sayil having to do with the ornamental scheme. On one of the friezes on the Palace is a depiction of the “Diving God,” or the “Descending God” as it’s sometimes called. The figure occurs in only four Mayan sites, all of them in the Yucatan Peninsula: Tulum, Chichen Itza, Sayil and Coba. Here’s a pic of the figure at Sayil:

It brings new meaning to the phrase, “bottoms up.” Debra Sandidge has an excellent article on the deity here. I don’t know why going about upside down has anything to do with bees, but there it is. The gods move in mysterious ways.

I give Sayil an 8 out 10. If you forget about any of the structures other than the Palace and just enjoy the forest walks, then it’s a 10 out of 10. So by all means, if you’re near the Ruta Puuc take a sidetrip to see both Labna and Sayil. You’ll be glad you did.