May 2018

Miagao Facade

There it is in all its glory, the UNESCO World Heritage Site church in Miagao. For those of you not in the know, Miagao is a small town 47 km (29 miles) west of Iloilo city on the island of Panay. Miagao is the only historical church in all the Philippines outside Luzon to carry the UNESCO site designation, so it is arguably and justifiably a Big Deal.

Miagao Buttress Tower

I’ve been to Miagao many times since I moved to Iloilo. My initial viewing took place during the week of my first visit in 2017; it was on the to-do list since I had researched the historical churches of Panay fairly extensively before my visit, hoping that the historical architecture of Panay would prove as much of a wow-factor as it seemed to me likely to do. If you’re a tourist and only on Panay for a few days to see some sights before you go off to do something else, like bake on a beach somewhere, then by all means Miagao should be on your bucket list and yes, Bridget, you will get a wow, no doubt about it. It definitely has the wow-factor going for it on first viewing.

Molo Church, Iloilo (St. Anne)

If like me, however, you live nearby and can go see it anytime you like, then your relationship with the building changes. I would at this point certainly not engage the old phrase, “familiarity breeds contempt,” but I’ll admit that the wow-factor diminishes fairly quickly with repeated visits. That may well depend on where you come from originally. For anyone from Europe or who has travelled extensively in Europe, where large and architecturally splendiferous churches are a dime a dozen, the interest of Miagao will decidedly be contextual in the local environment. The church cannot hope to compete with the likes of the cathedral at Chartres, for example. It’s impressive when one considers when it was built and who built it, out in the boondocks of Southeast Asia, very far away from anything similar architecturally speaking, with craftsmen on hand who likely knew much more about Chinese temples than they did about classical Greek architectural orders. But Chartres it ain’t, there’s no getting around that fact. It can’t even compete architecturally with at least one of the churches in Iloilo, the church in Molo (St. Anne’s, built in the 19th century), which has fine proportions in the facade and towers and transmits rather more direct an impression of the European original than does any of the four “Earthquake Baroque” churches singled out by the UNESCO heritage designation. The Molo Church also has a proper Spanish-style plaza in front of it. Mind you, it doesn’t give you the impression of being in Valladolid, but tracing things back visually to the Spanish point of origin is not a difficult task.

Miagao Facade Detail

Being one of those types who has a penchant for European architecture and has indeed bashed about Europe a fair amount looking at churches, I find my experience of the Miagao church becoming something like a visit to the mirror gallery at the fun fair. On first impression the European foundations of it stand out quite clearly, despite the unusual towers at the corners designed to provide structural reinforcement against earthquakes, which in this jumpy tectonic region have proven to be the bane of more than one ecclesiastical edifice. The facade is “exuberant,” perhaps that’s a good word, and upon first glance perhaps puts one in mind of Spanish or even Sicilian baroque with the fanciful piling of design elements atop each other. But clearly, we are not in Spain or Sicily, for you will search Valladolid or the Val di Noto in vain for palm trees or bananas on your churches. The more I see the Miagao church now, the more Asian it seems to me. It’s not so much a transplant in the sense that the Molo Church is, it’s much more a mutation of the original item.

The church was completed in 1797, at the tail end of the 18th century. When one considers the state of development Panay Island must have had at that point in time, it seems miraculous the Miagao church was built at all. That is the wow-factor in the whole business, to my present mind. A few Augustinian friars showed up on the scene and in predictable colonial fashion set about building something they knew from home with a workforce who had never seen anything of the sort and could only follow instructions. There is no historical information available about the craftsmen who did the actual work of construction, nor do we know from whose hand the architectural plan came. All is shrouded in anonymity. The UNESCO description mentions only “Chinese and Philippine craftsmen.” Given that Philippine craftsmen were not wont to work in stone, one suspects the bulk of the impetus came from the Chinese quarter, not the Filipino.

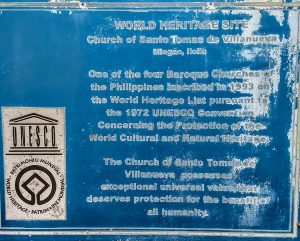

Miagao UNESCO Sign

I no longer think of the church in Miagao as something separate from the town. That shift changes one’s perception of the building considerably. It is, after all, a working parish church in addition to being a historical monument. The local people think of it primarily as a working church, their church, the historical element being incidental, really. Life goes on all round it in typical Filipino fashion; it makes very little difference that the church sitting across the street from the town plaza has been singled out by UNESCO for special distinction. The state of the UNESCO notice sign tells that tale quite effectively — it has definitely seen better days and could use replacement. But I expect if one asked when that might happen, one would inevitably hear that well-worn Filipino stock phrase, “We don’t have budget for that.”

Miagao Public Market

Beach at Miagao

The town itself is quite lively and when I go out to Miagao on my motorbike the town is the destination, not just the church. Miagao’s public market is a source of endless fascination. It’s HUGE for a town of its size and chock-a-block full of things of all description. Great fun for a wander that can easily take up half the day. The beach is just a short walk down the street from the church and affords a lovely view of the mountains in neighboring Antique. I also look forward to lunch at the Cafe de Hablon, a charming little place right across the street from the church, with waitstaff who are without doubt the most eager and accommodating of any restaurant I’ve ever patronized in the Philippines. And then, of course, there is the fact that Miagao sits on the edge of the Central Panay Range of mountains. The vistas from the streets as you move about here and there are delightful, with peaks looming in the distance, and from Miagao they appear to be within touching distance, unlike in Iloilo, where they are a presence on the distant horizon only.

After becoming acquainted with the historical churches in southern Panay — for there are others in Guimbal, Tigbauan, Alimodian, and of course the historic churches in Iloilo City itself (the Molo Church and the Cathedral of St. Elizabeth in Jaro) — I found that they didn’t convey to me a clear and immediate sense of the Spanish colonial past, which I had hoped would be the case. They’re certainly extremely interesting historically, but architecturally speaking they are more astonishing than they are reminiscent of European architecture. No Spanish or Italian architect with a reputation good enough to have been given a commission for something similar in Spain or Italy would devise a facade like the one the Miagao church sports. The Miagao facade is clearly the result of people who have no clue about European architecture going for broke and doing something as fancy as they can manage according to whatever drawings they’ve been handed. And it’s all good, to be perfectly honest. If what you’re after is strict adherence to Palladian proportions or a classic example of the Baroque style of a particular school, then you need to go to Europe, not to Panay Island. I loved living in Europe because everywhere I turned I found buildings from a variety of historical periods, even in small out-of-the-way places you’d expect to have nothing. There’s nothing like that in the Spanish colonial lands of the Philippines. The Miagao church sits in the town as an anomaly, not as a member of a historical architectural ensemble.

Miagao Church Doorway

Miagao Window Detail

When I go to Miagao now I still visit the church when the day is fine and the light is good to study the architectural detail. The wow factor is gone, yes, but the fine work to be found on the windows and doors is lovely and worthy of repeated attention. There is also some fine ironwork on the windows, a trait shared with others of the historical churches of Panay, especially Alimodian. For me, as well, it’s always amusing to see what things are growing out of the stonework, where you’ll find a fine assortment of ferns poking out from the corners and many-colored mosses growing here and there. I remember finding grass growing on the roof of the Cathedral in Ventimiglia, Italy when I passed through there and had a stomp about the old town. Seeing such a thing after living in Germany for two years, my reaction was at first disbelief, then rapid dismissal. “Well, if they can’t even be bothered to keep the grass from growing out the roof of their cathedrals, I need know nothing more about these Italians …” That sort of thing. In Miagao, however, it’s perfectly fine. Of course there will be ferns growing out of the side of the church, duuuh. They grow everywhere here. So it’s all in good order in Miagao and has its own charm to add to the prospect.

There’s something cozy about finding a Big Deal architectural monument changing fairly quickly into “oh yes, the Miagao church, lovely thing isn’t it.” If you see it as a tourist it delivers on its UNESCO promise, I think — it certainly did for me, and I’m not an easy customer by any stretch of the imagination. I’m fine now with seeing it as a familiar and welcome landmark when when I come into town from Iloilo. No need to be wowed, just a “howdy do” and a bit of a look-see does the trick. It’s enough to know it’s there, as it has been for centuries and, one hopes, will be for many more to come.

Miagao Church Side View