October 2019

With a base in Merida you have any number of easy day trips available to sites in the vicinity. That’s the reason I based myself in Merida for the first five days of my two-week trip to the Yucatan Peninsula. I had wheels the whole trip so I was free to go in any direction I chose. After going north to Dzibilchaltun I decided on a lark it was time to go south, and so south I went to Sotuta de Peon and Mayapan. Sotuta de Peon figures in a program I saw on YouTube, an installment of “Las Once Mas” produced by Canal Once and hosted by Miguel Conde (in Spanish, of course). Each program shows 11 of the most interesting sites of a particular Mexican state identified by survey of inhabitants of that state. I watched the program on Yucatan more than once, noting carefully both the sites and all the information the host conveyed. Sotuta de Peon figures in the program’s list of sites but Mayapan does not. For the tip about Mayapan I have the website “The Mayan Ruins Website” (here) to thank. It so happens that Mayapan lies within easy reach of Sotuta, so it made all the sense in the world to combine the two places into a day trip. Sotuta de Peon is only 32 km from Merida and Mayapan only 42 km. With a car it’s child’s play. I shudder to think what the trip would be like using public transportation — so let’s not think about it. Some things are better left unexamined.

With a base in Merida you have any number of easy day trips available to sites in the vicinity. That’s the reason I based myself in Merida for the first five days of my two-week trip to the Yucatan Peninsula. I had wheels the whole trip so I was free to go in any direction I chose. After going north to Dzibilchaltun I decided on a lark it was time to go south, and so south I went to Sotuta de Peon and Mayapan. Sotuta de Peon figures in a program I saw on YouTube, an installment of “Las Once Mas” produced by Canal Once and hosted by Miguel Conde (in Spanish, of course). Each program shows 11 of the most interesting sites of a particular Mexican state identified by survey of inhabitants of that state. I watched the program on Yucatan more than once, noting carefully both the sites and all the information the host conveyed. Sotuta de Peon figures in the program’s list of sites but Mayapan does not. For the tip about Mayapan I have the website “The Mayan Ruins Website” (here) to thank. It so happens that Mayapan lies within easy reach of Sotuta, so it made all the sense in the world to combine the two places into a day trip. Sotuta de Peon is only 32 km from Merida and Mayapan only 42 km. With a car it’s child’s play. I shudder to think what the trip would be like using public transportation — so let’s not think about it. Some things are better left unexamined.

SOTUTA DE PEON

Sotuta de Peon (organizational website here) is an astonishing presence in its landscape. In its heyday it was a working sisal (“henequen” in Spanish) plantation with industrial-scale operations. It has been developed as a combination historical site and resort. If you want to explore what the old sisal plantations were like and how the sisal industry operated, there are tours available at Sotuta de Peon that will give you clear insight into both the history and processes of the industry. If you want a resort stay out in the countryside in a beautifully organized and impeccably maintained park-like setting, then that option is available, as well. You can take either one or combine them as you like. I engaged the hacienda on different terms: as a simple observer who came to have Yucatecan food in the restaurant, which receives excellent reviews from various sources. I was free to wander round the public areas and did exactly that after lunch. When I left the place I felt I had had an opportunity to get a good sense of its history and its life without taking the organized tour out into the fields and to the buildings where sisal is still processed as part of the historical tour.

I must say that the approach to the hacienda left me a bit nonplussed. There’s a town of Sotuta of which the hacienda is ostensibly an appendage. The reality of the situation, however, is that the town is no more than two mean streets giving the impression of a place that’s recently suffered some major misfortune without any disaster relief having shown up yet. It barely qualifies as a village and what village there is presents a face from which one is likely to look askance in distress. You pass through it quickly to the hacienda and thence into a completely different world, different from the village by entire orders of magnitude. I checked my impression of the town on the way out after the visit to the hacienda and found that no, indeed, I hadn’t imagined it in any state other than the one it in fact inhabits. More’s the pity. I’d have been only too happy to be proven wrong.

The public areas include the chapel, the restaurant with its enormous lawn space and the environs of the main house. Here are some pics to give an idea:

Lunch was the first order of business so let me describe the restaurant. I travelled with a friend from Merida and we were the only guests at the time. The restaurant is open-air and there was a lovely breeze blowing on what was a typically hot day. It was blissfully quiet and I thought to myself, “This is going to be a lovely lunch.” Shortly thereafter the speakers started emitting mariachi music at a volume that made conversation an effort. It’s part of the culture, I know, but it’s part of my culture not to be assaulted by loud music every time I sit down at a table to eat something. I said nothing but wished I were hearing the breeze rather than somebody wail on about lost love. The food was superb. I had panuchos with cochinita pibil, which is roasted pork with spices done in a traditional Mayan way by pit-roasting. Delicious. If you ever find yourself with an opportunity to visit the hacienda and sisal production means nothing to you, go for the food. You’ll be glad you did.

Back in the day sisal was called “green gold” because of the enormous wealth it produced for plantation owners in the Yucatan Peninsula. The haciendas often operated as their own towns, with a chapel and medical facilities and stores, something like the company towns we know from American history. The “big house” as it would be called on an American plantation is an impressive but not palatial building, quite modest in its ornamentation. The grounds surrounding it are lovely and there’s a whimsical frog fountain in the front garden I found particularly amusing. The main residence now serves as a hotel accessible only by guests, so I only have pics of the outside.

Then there’s the chapel, which as hacienda chapels go is quite a handsome specimen, I think. The exterior looks freshly painted so it appears as tidy as the rest of the compound and the interior has obviously been modernized to some degree since I don’t think the cross-shaped window can be original. It’s a lovely little building.

It’s clear that a lot of money has gone into the development of the facility and a goodly amount obviously goes into maintenance. It would be a good resort stay if a person wanted to get away from the urban areas and spend some time in the countryside. I’m glad I found it in the Canal Once program and glad I went. It’s certainly worth the trip.

MAYAPAN

This Mayan archeological site is not on the tourist hotspot list so a visit doesn’t involve hordes of tourists like you find at Chichen Itza. The Mayan Ruins Website gives this excellent description (webpage here):

Mayapan is a Post Classic Period (950-1500 A.D) site that lasted until the 15th century, when it was destroyed and abandoned through internal strife. Continuing excavations appear to be pushing the date of founding further back. There is ceramic evidence of earlier underlying settlement. In many aspects it mimics the architecture at Chichen Itza, the earlier, great Maya site in central Yucatan. It was a shared capital between the two major cultural groups of the time period, the Xiu and the Cocom.

Despite the fact that the city was wracked by civil war in the end, it was a vibrant cultural and economic power. Long distance traders and foreign ideas were welcomed into the city. There is evidence of Aztec influence in some of the mural paintings. It has even been suggested that the Aztec had their eye on the city as a future vassal state. The city had a cosmopolitan atmosphere and an expanded world view.

And from the Wikipedia page on the site (here):

Mayapan became the primary city in a group of allies that included much of the northern Yucatán, and trade partners that extended directly to Honduras, Belize, and the Caribbean island of Cozumel, and indirectly to Mexico. Though Mayapan was ruled by a council, the Jalach winik and the aj k’in (the highest ruler, and the high priest) dominated the political sphere. Below the two primary officials were many other officials with varying responsibilities. The range of classes went from the nobility, down to slaves, with intermediary classes in between. The social climate of Mayapan was made complicated by the antagonistic relationship between the factions of nobles, which were often arranged by kinship (Pugh 2009; Milbrath 2003). In 1441, Ah Xupan of the powerful noble family of Xiu became resentful of the political machinations of the Cocom rulers and organized a revolt. As a result, all of the Cocom family, except one who was away in Honduras conducting trade, were killed, Mayapan was sacked, burned, and abandoned, all the larger cities went into decline, and Yucatán devolved into warring city-states.

Archaeological evidence indicates that at least the ceremonial center was burned at the end of the occupation. Excavation has revealed burnt roof beams in several of the major buildings in the site center.

The site of Mayapan was abandoned sometime in the 15th century. There has been some dispute over when the actual abandonment took place. However, written records state that the site was abandoned in A.D. 1441. There appear to be several contributing factors to the abandonment of Mayapan. Around A.D. 1420 a riot was started by the Xius against the Cocom which culminated in the death of nearly all (if not in fact all) of the Cocom lineage. Pestilence may have been involved in the subsequent abandonment of the site by the remaining Xiu inhabitants. There were several sources of evidence to support this interpretation. Evidence of burned wood was found inside of structure Y-45a as well as burned roofing material on many of the other structures that was dated to around the time of the collapse in K’atun 8 Ahua (roughly A.D. 1441–1461). A mass grave in the main plaza, and bodies in a burial shaft covered in ash were dated to around the collapse and showed signs of violence, some of the bodies still had large flint knives in their chests or pelvises, suggesting ritualized sacrifice. Smashed vessels litter the floors of the Y-45a complex that date to around A.D. 1270–1400, prior to the documented collapse of Mayapan. A vessel bearing the glyph K’atun 8 Ahua was found on the floor of this complex. From this they have posited that the complex was abandoned finally when the city fell (Lope 2006; Milbrath 2003). After A.D. 1461 there is little evidence of altars and burial cists being constructed after 1461, suggesting that the site had been abandoned by this point (Lope 2006). Very little evidence has been found to support later usage of Mayapan. Copal from an altar was found in the Templo Redondo compound that may suggest later pilgrimages to the Castillo de Kukulkan. However, these samples date to the industrial era and may not be valid, so any assumptions based on this evidence would also not be valid (Lope 2006:168).

The time-worn myth about the Mayans being peaceable folk who looked at the stars and spent their time calculating dates using their immensely complex calendar system is dashed to bits by the archeological evidence, as the Wikipedia excerpt makes clear. Before arriving in Mexico I read Carlos Pallan’s excellent Breve historia de los mayas which details some of the tribal wars between various Mayan states like Tikal and Calakmul. They were perhaps a few notches below the bellicosity of the Aztecs but only a bit. War figured into their Business As Usual on a scale that must have disrupted the social fabric and exacerbated their tenuous relationship with the natural environment.

Having never before been in the Yucatan Peninsula I had no lived experience of the natural environment. On my first visit to a Mayan site in Dzibilchaltun I immediately became aware of how poor the soil is. The entire Yucatan Peninsula is karst country, pure limestone, and the soil sits on top of the rock in a thin layer that must have been hell to cultivate. No wonder collapses occurred more than once in the history of Mayan civilization. Slash and burn agriculture in such an ecosystem is a time bomb waiting to explode. Increase the number of people past a certain point and you’ve got Malthus on top of you like a ton of bricks. My astonishment grew with every site I visited at how the Mayans had managed to create what they did. Some areas of the Peninsula — e.g. the Puuc region — lack cenotes and rely for fresh water only on rainfall. Yet the Mayans built major conurbations in such places and carried their civilization to a high point of development. Amazing. Hats off to them for being clever enough to figure out how to do that with such meager resources at their disposal.

The day I visited Mayapan there were no more than six people at the site. When I arrived I was the only one, the others came only later. So for a good hour at least I had the site entirely to myself. I’ll give you the gallery of pics first and then comment on the buildings.

Like Dzibilchaltun, Mayapan doesn’t convey to the modern observer the scale of Mayan conurbations. I didn’t get that full story until I went to Uxmal where it became crystal clear that Mayan sites were indeed cities in the true sense of the word. Some of them were BIG cities. Mayapan was the last major Mayan capital on the Yucatan Peninsula and was also a big city, I think, but that fact doesn’t strike one from looking at what’s available for viewing today. Most of the city still lies unexcavated. If it were all brought back magically to the state it was in before its collapse and abandonment, I expect it would be quite impressive. As it is it’s impressive enough with its two pyramids and the observatory. It took my fancy because it’s the first site at which I saw sculpture, since there isn’t any at Dzibilchaltun.

As for a worthwhile description of the buildings on view, I can do no better than refer you to the excellent discussion at The Mayan Ruins Website (Mayapan page here). What you see in the pics are the two major pyramids, both reminiscent of the one at Chichen Itza. Equally hat tipping to Chichen Itza is the round structure reminiscent of the observatory at Chichen Itza. I went inside this one and found that the interior is almost entirely taken up by masonry, so it can’t have been an observatory. I don’t think archeologists have quite figured out what purpose it served. In any case, it looks better from the outside than from the inside, that much I can vouch for.

The panaorama shots give some impression of the scope of the site. In terms of surface area it’s smaller than Dzibilchaltun although it has far more and far more elaborate structures on display. I’d like very much to see the scope of the area where buildings have been found. Most Mayan sites open for visitation show less than 20% of the buildings associated with the historical site, so we gain a false impression of the site’s full extent by limiting our attention only to those buildings that have undergone excavation. Like Dzibilchaltun, Mayapan doesn’t fire the imagination to conjure up the life that went on there. It seems designed to be museum-like, mute, unevocative of the busy life that doubtless went on there as a major capital of the Mayan world. I found the site lovely, to be sure, but it seemed like an open-air museum rather than a tantalizing remnant of a disappeared world.

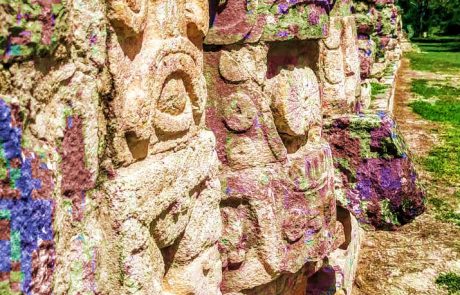

As I mentioned, Mayapan has some sculpture on display, so let me give you those pics:

As for the iconography, I’m no expert so I can only offer the bits and bobs I know. The two square-faced masks are the Mayan god of rain, Chaac. He was a very Big Deal in the Mayan world, not difficult to understand if you consider how vitally important rain was to folks living in the Yucatan Peninsula. Rain was the lifeblood of Yucatec Mayan civilization because it grew their crops, there are no rivers or streams or lakes on the Peninsula, only cenotes, which aren’t distributed with particular care for human convenience as sources of fresh water for domestic or agricultural use. Rain was the kingpin and Chaac was the guy you needed to keep happy. He shows up so often in Mayan sites on the Peninsula that I began in Uxmal to cackle the name like a chicken, “Chaac Chaac Chaac …” I doubt he was amused but I wasn’t struck by lightning so he’s obviously willing to turn a deaf ear to blasphemy from ignorant foreigners. 🙂

I have no idea who the homunculus in the third pic is, but he looks grumpy. In point of fact, all the faces in Mayan sculpture look grumpy. Obviously the Mayans never had a Raphael and there were apparently a lot of bad hair days. After a few visits to Mayan sites with lots of figures I began to look at Chaac and think, “A spoonful of sugar …” These foreigners, really …

I enjoyed the Mayapan site a lot because it allows you to get up close and personal with the buildings, which isn’t always possible at the more developed sites like Chichen Itza and Uxmal. I ran around at complete liberty to see whatever I wanted in whatever degree of detail took my fancy, so I come away from the experience with a sense of fondness for Mayapan from that close enounter. It’s well worth the visit and if you’re in the Merida area with the right kind of transportation it should definitely find its way onto your bucket list.