November 2019

The Ruta Puuc — “the Puuc route” in plain English — was a fuzzy concept in my mind until I was actually on the ground in the Puuc region, at which point all was revealed. So let me clear it up for you if there’s any doubt in your mind. The Puuc region is an area in the northeast of the Yucatan Peninsula. It’s crammed full of Mayan ruins, including Uxmal, one of the major archeological sites of the Peninsula. Puuc is also the name of a specific architectural style developed in that area. Here’s the skinny from the Wikipedia page on the region (here):

The Ruta Puuc — “the Puuc route” in plain English — was a fuzzy concept in my mind until I was actually on the ground in the Puuc region, at which point all was revealed. So let me clear it up for you if there’s any doubt in your mind. The Puuc region is an area in the northeast of the Yucatan Peninsula. It’s crammed full of Mayan ruins, including Uxmal, one of the major archeological sites of the Peninsula. Puuc is also the name of a specific architectural style developed in that area. Here’s the skinny from the Wikipedia page on the region (here):

Puuc is the name of either a region in the Mexican state of Yucatán or a Maya architectural style prevalent in that region. The word “puuc” is derived from the Maya term for “hill”. Since the Yucatán is relatively flat, this term was extended to encompass the large karstic range of hills in the southern portion of the state, hence, the terms Puuc region or Puuc hills. The Puuc hills extend into northern Campeche and western Quintana Roo.

The term Puuc is also used to designate the architectural style of ancient Maya sites located within the Puuc hills, hence, the term Puuc architecture. This architectural style began at the end of the Late Classic period but experienced its greatest extent during the Terminal Classic period.

Just to be clear about where the region lies, here’s a map:

Everywhere you see a triangle in the map there’s a Mayan ruin. The orthography doesn’t indicate relative size, however — Uxmal is the Big Deal in the region, so it should have letters twice the size of any other site. Be that as it may, you can see from the number of triangles that there are Mayan ruins all over the place. That’s one of the attractions of the area. It’s certainly what drew me there.

The Puuc hills are exactly that — geological prominences that take on far more significance as hills than they otherwise would if they were not exceptions to the rule of land as flat as the proverbial pancake over most of the Yucatan Peninsula. I grew up with mountains and have always loved mountainous landscapes with an affection differently pitched than any attachments I may form to flatlands. When I drove from Merida (flat as a pancake) down to the Puuc region to begin my explorations of the Mayan sites I came at last to the hills — real hills! — and nearly stopped the car just to gawk at them. Contour in the landscape! Wow! How cool is that! I was immediately a fan and the Puuc region is my favorite of any area I visited during my two-week trip, even without the Mayan sites, which are also top-notch.

The “Ruta Puuc” is a tourism term that I thought originally in my ignorance applied to all the Mayan sites in the region. Wrong. It applies to four sites south of Uxmal — one along the main highway (No. 261) and three along another highway that branches off 261 south of Kabah. From the Wikitravel site on the Ruta Puuc (here) comes this handy list:

Mayan archaeological sites on the Ruta Puuc

- Uxmal – important Mayan spiritual center, it features the Pyramid of the Magician

- Kabah

- Sayil

- Labna – famed for its entrance arch, its Palace of Columns, and for an obelisk (Stele 9) that is believed to be a huge phallic symbol

- X’lapak

- Loltún – a system of underground caves (cenotes) in which one can see evidence of Mayan ceremonial practices

I’ll fess up right at the beginning — I didn’t go to Kabah, which is right on the main highway. I spent so much time — and destroyed one pair of shoes — going through Labna and Sayil that I contented myself with seeing of Kabah what’s visible from the parking lot on the highway. Although I was tempted to go see the “Codz Poop” just to snigger at the name, the morning grass drenched with dew and the fact that I had only one pair of shoes left to last me through the rest of the trip made me think twice and choose to view things from the sidelines. Neither did I go to X’lapak, which seemed after the massively interesting time spent at Labna and Sayil bound to induce anticlimax. Besides, it’s nice to leave something unseen to give yourself an excuse for going back at some point in the future, right? I didn’t go to Loltun because I’d done the cenote thing and I’m not a spelunker. I like the sky above me and the sun shining, thank you very much. All these evasions turned out to be strategic, however, because both Labna and Sayil are astonishing sites providing such unique experiences that I easily spent all the time I had going through them. I don’t regret for a single moment having devoted all my time to them. The investment returned more than ample gain from both the aesthetic and experiential points of view. So, let’s begin at the beginning: Labna.

To tee things off I’ll provide some useful information from themayanruinswebsite.com, my go-to source for info on individual Mayan archeological sites:

Labna is a stunning, small Classic Maya site (600-900 A.D). It features pure Puuc style architecture such as colonnettes and mosaic designs. There was a reduction of population during the Post Classic(900-1200 A.D.), though some construction was undertaken. The site was abandoned around 1200 A.D.

The site was rediscovered by those intrepid explorers John Lloyd Stevens and Fredrick Catherwood in the 1840’s. Edward Thompson, American Counsel in Merida, conducted the first excavations at the end of the 19th century. Exploration, excavation and restoration work continues to this day.

I agree 100% with the word “stunning” in the first sentence. And I point out the last sentence: “… restoration work continues to this day.” There’s ample evidence of that fact, something I’ll point out in the pics.

I arrived at Labna from my hotel in Uxmal at opening time, about 9AM. I was the only visitor — something I hardly expected but welcomed with delight after dashing about Uxmal the day before skirting my way past the tour groups. Even more delightful is the ability to get right up to the buildings, something not possible at Uxmal. Once past the entrance and in sight of the first group of buildings I left the gravel path and crossed the grass to it. My feet were immediately soaked, since heavy dew collects on the ground during the night in the Puuc region. The pair of shoes I was wearing became the sacrifice I offered to Chaac :-). They certainly didn’t survive the experience, so I hope he was happy.

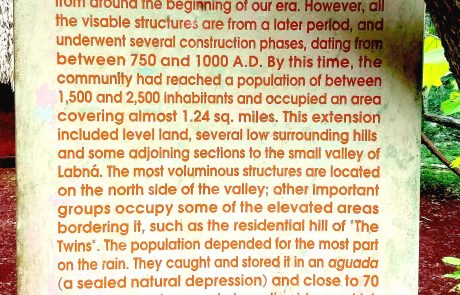

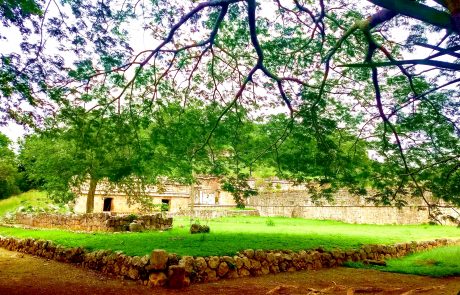

To the pics, at long last — here’s the first group:

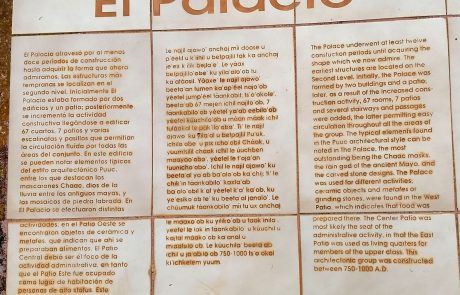

Yes, shiver your timbers, thar’s English near them thar buildings. How convenient for the monolingual and a gesture of kindness to visitors in this remote part of the Yucatan who might find English easier to handle than Spanish or Mayan, the languages of the other two blurbs. It’s good information and I was glad to have it. The pics I took as I wended my way toward the buildings — the “Palace” group in fact — show the predominance of the natural environment over the architectural one. When one reads books about Mayan sites they usually appear free and clear, like cakes put tidily on a cake platter and served up to our attention. In reality there is dense forest — jungle, actually — all round and when the Mayans abandoned their cities the vegetation made quick work of disappearing the works from the hand of man. The sites one visits have of course had the jungle scraped off them so you can see what’s there, but let it never be forgotten that the jungle makes the rules, not the human beings who build things to their own purposes and glory. The jungle rules the roost at the end of the day. Always has, always will.

It was instructive to me to view Labna after seeing Uxmal. Uxmal’s buildings are quite sophisticated and show a high degree of architectural prowess and imagination. With both Labna and Sayil we are in a different league, a bit farther down the pecking order. There’s absolutely nothing wrong with that — we can’t all be Einsteins or Michelangelos. Coming as I do from a rural backwater where the production of something as interesting and elaborate as the buildings at Labna would be well beyond the reach of local talent, I didn’t in the least feel I was slumming after having been Uptown at Uxmal. Not a bit of it. The builders of Labna knew a thing or two and had more than a splash of talent. Let’s have a look at the Palace group up close and see what we can see:

Obviously we’ve gone OCD on the Chaac thing, again — that’s to be expected given the territory. At least there’s some variation in the form of the Chaac mask, so I suppose we should count ourselves lucky. It could be like one of Andy Warhol’s Campbell’s soup paintings, so let me not cavil. The proportions of the masks are pleasing to me — they convey strength and severity as they were meant to do, I think. They also offer a pleasing symmetry of elements, axial symmetry being very much in the saddle here. Just as at Uxmal there are pig-snouted Chaacs as well, which has either a meaning or a practical purpose that completely escapes me. Since I found the prospect of trying to Google “Chaac pig snouts” in Spanish too daunting without strong drink, I decided to leave well enough alone. Somewhere in the literature is the perfect explanation of why some Chaac masks have pig snouts. May the information gods reward you richly should you hanker after such knowledge.

The ornamental groups leave me a bit befuddled as well as a bit bemused. Since I was raised on European ornament from the Renaissance and Baroque periods, I’m quite flexible when it comes to ornamental syntax. I find late Baroque/Rococo swirls completely charming and would never in a million years dream of imposing strict axial harmony on them. That being said, I also realize that European ornament accomplishes a very different ornamental agenda than what we see here in the Labna pics — so it seems to me. The two pics showing the ornamental panels leave me at a complete loss how to explain either the elements or their organization. When I stood in front of them looking intently at them, after a few moments I said to myself, “Well, it’s probably just whatever felt right that day, so I probably shouldn’t have an aneurism trying to figure it out.”

I stand by that assessment. The elements and their arrangement obviously show some concern for imposing pattern and symmetry on the pictorial space they enclose. But why those particular elements in that particular arrangement? No clue. It seems completely aleatory to me. I have no objection to that state of affairs, none whatever. It represents an artistic freedom I can appreciate to the full. Maybe one day it will dawn on me what it’s supposed to mean, if it’s supposed to mean something in particular.

From the Palace group you move on a sacbe (white road) to the group of structure with the famous arch and the “Mirador” stuck up on its little hill. Here are some pics of the proceedings:

The first two pics gave me a lived sense of what a sacbe (white road) is. It’s essentially a low platform that makes a road between one place and another. It involves the use of blocks and rubble fill, just like wall construction uses. When you consider that some of the sacbeob are some 60km in length, the incredible amount of work and material required becomes crystal clear. It’s something like building an Egyptian pyramid all strung out over a length rather than piled up to point. Duly impressed by that on which I trod, I headed over on the sacbe toward the Arch group, where the famous free-standing arch of Labna is found. You see it in the subsequent pics in all its glory. I was duly impressed by it as I stood before it, but in the evening after seeing it and sharing some pics with a friend of mine I wrote, “They probably got the idea for it from the Marble Arch at Hyde Park, but obviously they’re not very good with round things.” LOL. Reading instructs me that the Labna arch represents a high point of Mayan arch architecture, of which another example is to be seen at Uxmal near the Nunnery Quadrangle. I’d give the olive crown to the architects at Labna in the arch competition, to be honest. It’s really very well done and the ornamentation has the arch at Uxmal beat six ways to Sunday. And boy, let’s hear it for strict axial symmetry in the decoration of the frieze at the top.

The next to last pic shows the “Mirador” (which means “viewpoint”) building silhouetted against the (grey, dingy) sky. I didn’t bother to climb up the debris slope to get a close look. The cockscomb grille on the front struck me as absurd as the topknot in the woman’s hairdo known as a “pompadour.” It has shafts of wood sticking out the front which gives it a base utilitarian look, as though it were meant to serve as a place to hang out the wash. In all of the reading I did I never came across any explanation for the function of the structure. Let’s allow it to repose in the mystery that surrounds it and keep moving. Here’s a pic of the front from as close as I could get without climbing up the scree slope:

Go figure …

I called attention to one of the lines in the English-language blurb shown at the beginning of the post. “… restoration work is still ongoing.” Or something to that effect. Well, on your way from the Palace group to the Arch group you see plain evidence of the state of things as they must have been before any restoration/reconstruction was done. Here’s the pic:

With a little imagination one can picture it in its original state, standing square and tidy against the backdrop of the jungle. Seeing this jumble of stones that once was a perfect building brought home to me the incredible amount and difficulty of the work involved in restoration/reconstruction. So to all of those archeological types who have sweated and grunted lifting stones to put them back where once they stood, hats off! Without your fine work we’d all be much the poorer for missing out on what the Mayans accomplished.

After spending a few hours with the buildings at Labna I scooted down the road about 10km to visit the very interesting site of Sayil. So stay tuned, that other shoe will drop in the next post.