February 2019

The reputation of Rebecca West has trailed off drastically since her death in 1983. In her prime she was considered a very Big Deal, justifiably so. Having read many of her works dating from all periods of her active life as a writer, it’s clear to me that she was one of England’s textual powerhouses over her entire career. Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, her account of travel in the former Yugoslavia and the work most often considered her masterpiece, is an astonishing production. But the young Rebecca West is equally astonishing.

She wrote masterpieces of another sort when she was just a young thing under the age of 25. As a journalist working for suffragist or socialist newspapers she let fly commentary, literary critique and the equivalent of investigative reporting that leaves the objects of her contemplation in the dissected state one might expect to find on the floor of an abbatoir. There’s no putting Humpty Dumpty together again after Miss West has finished taking him apart, you can be sure on that account. It goes far beyond what could be called a dog worrying a bone. It’s more a case of a pit bull getting hold of a cat.

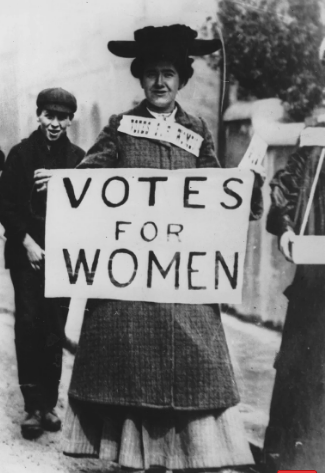

Editor Jane Marcus has done us all a great favor by collecting work written by the youthful West and publishing it in the book The Young Rebecca: The Writings of Rebecca West 1911–1917, available both in print and in Kindle format. It was published in 1989 and I had the good fortune to come across it not long after it appeared. It’s been my constant companion ever since. West herself commented in Black Lamb and Grey Falcon that most of her work had appeared as isolated pieces in newspapers and magazines. As far as bulk goes that’s doubtless the case, although her books are many and hardly secondary to her work as a journalist. Until the publication of The Young Rebecca, however, there was no easy access to her earliest work, written between the ages of 19 and 25 when England was in the throes of the Suffragist movement. Those were heady days for a young woman of sharp mind and fierce mettle and West more than rose to the challenge of her times. She exploded onto the literary horizon like a supernova. The pieces collected in The Young Rebecca show that early brilliance very clearly.

As I sit here at my desk in 2019 buried under the linguistic detritus of the modern world, my mind boggles in the attempt to understand how it was possible for a young woman of 20 with no more than a spotty education in a girl’s school in Edinburgh to write the following:

Barricaded from the fastidious craftsman behind the solid Tottenham-Court-Road workmanship of her mental furniture, Mrs Humphry Ward has been able to preach her gospel unappreciated by revolutionaries. This is a pity. Because Mrs Ward reveals to us the psychology of the clergyman class — the class which throughout the Victorian era peopled the Church and the univerisities to the exclusion of any other. With the single exception of the scientist group, they have sent no message of inspiration to this generation. … But it helps us to understand the House of Commons if we can grasp their point of view: and that is most lucidly and naively shown in the works of Mrs Humphrey Ward.

Even her deficiencies are of value to the student. For instance, at first sight it seems merely a very damning proof of the worthlessness of Mrs Ward’s writing that she should have written her two most pretentious works, Robert Elsmere and The Case of Richard Meynell, about a national movement which could not exist, but a movement which she describes as sweeping over the country and turning the hearts of Englishmen to flame. This modernist movement, which aimed at regulating the Church of England’s doctrine and ritual according to the conclusions of historical research upon the life of Christ, is alien from, not only the Englishman, but the human mind. Jesus of Nazareth sits in a chamber of every man’s brain, immovable, immutable, however credited or discredited. The idea of Christ is the only inheritance that the rich have not stolen from the poor. It is now a great national interest (not a faith), and as such is treated with respect, and as securely protected from ‘modernising’ as the tragedy of Hamlet. And although Mrs Ward has been ‘turning her trained intellect’ (to quote her publisher) on the universe for nigh on sixty years, that has not struck her. She regards the Englishman as going to church with the same watchful eye of possible improvements as when he attends the sanitary committee of the borough council. She does not understand that the Englishman, having discovered something that, whether true or not, is glorious to the human soul, is not going to tamper with it. This misunderstanding is so typical of her class. For, see how in the House of Commons the respectable always try, by encouraging mean thrift, to rob the poor of their improvidence, which, uncomfortable as it is in its results, is nevertheless their one means of protest against their conditions.

I’d hardly expect that kind of utterance from a 20-year-old today. What I’d look for these days is something on the order of, “WTF?.” Quite a difference a century makes, don’t you find?

Language reflects thought, so not only is the language astonishing but so is the conceptual range. It should be said that Mrs. Humphrey Ward (Mary Augusta Ward, info here) was in her own literary context a Big Deal. West’s dismissal of her in this piece from 1911 was bold in the extreme because Mrs. Ward was revered as one of the Victorian literary greats. But she was against votes for women and founded the Women’s National Anti-Suffrage League. West wrote her piece for The Freewoman, a Suffragist newspaper. Small wonder there’s no question of their seeing eye to eye, and small wonder that West savages Mrs Ward like the pit bull getting hold of a cat that I mentioned. West works her dismemberment skillfully, however, meeting Mrs. Ward on her own ground and cutting with the incisors of historical and social analysis. It’s certainly possible to disagree with West’s points but they can’t legitimately be dismissed out of hand. West has done her homework and prepared her arguments too carefully for anyone to do that without looking a fool.

I’ve come to assume that biographies of English people will leave my hair standing on end. After watching a few episodes of the UK version of “Who Do You Think You Are?” I gave up because the life stories uncovered were just too depressing — civil servants with drinking problems who subsequently go rogue, families thrown into Victorian workhouses where half the children die, tenant farmers burned out of their houses in order to clear land for sheep — I just couldn’t take it anymore. West has a background cut from similar cloth, with a feckless father who abandoned the family when Rebecca was eight years old, after which the family struggled on in Edinburgh, her mother’s birthplace. Things moved forward by the skin of the teeth until Rebecca began her paid work as a journalist. I know relatively little of her early biography, but it’s enough, I don’t need to know more.

Her life story after making a name for herself as a young woman hasn’t been a subject of great interest to me, although I’ve occasionally been tempted to read one of the biographies currently in print. The bits and bobs I know about her later life lead me to suspect I’d find my eyes rolling back in my head with the only reward for my efforts a cleft between the highest estimation of the writer and confusion or distress about the human being. I’d rather not go there, to be honest. I much prefer to stick with West the author, leaving all the muddles and befuddlements of her personal life (and there are many) well out of view.

It stands to reason as West became an established figure in the literary firmament of her day that her writing changed. While she never hesitated to speak as she found, she mollified the expression of her opinions and insights after she hit the big time. Fair enough. When you reach a particular position in the literary establishment there are expectations to meet and a public image to maintain in exchange for cash and kudos. In West’s case, however, the change involved a certain amount of posturing, which I suspect stems from the gap between the public and private persons she was. From the Wikipedia page on West (here) comes this astonishing revelation:

In 1930, at the age of 37, she married a banker, Henry Maxwell Andrews, and they remained nominally together, despite one public affair just before his death in 1968. West’s writing brought her considerable wealth, and by 1940 she owned a Rolls-Royce and a grand country estate, Ibstone House, in the Chiltern Hills of southern England. During World War II, West housed Yugoslav refugees in the spare rooms of her blacked-out manor, and she used the grounds as a small dairy farm and vegetable plot, agricultural pursuits that continued long after the war had ended.

West’s husband was largely responsible for the stately pile, a Regency number near High Wycombe in Buckinghamshire where West lived for almost 30 years until her husband died in 1968, after which she sold up and decamped to London. It’s quite the spread:

By the point she became mistress of Ibstone House there were obviously appearances to be kept up, however radical her opinions. Gone were the days of the free-spirited young woman knowing her own mind and facing the world with only her rapier wit and her courage girding her loins.

In the early writing there is no posturing. There’s only the firebrand journalist facing life in the Edwardian era as a young woman finding her way in the world, all the while putting that world under the microscope and then the scalpel. In my opinion the authorial voice West found in the first phase of her life forms the basis for everything that followed. Without that firebrand youth she’d never have written the works later considered to be her masterpieces, works that deserve the appellation without any shadow of doubt.

The citation I gave above is from the article in The Freewoman entitled, “The Gospel According to Mrs. Humprey Ward.” The Young Rebecca also includes the complete essays West wrote for The Clarion, a socialist newpaper published in England between 1891 and 1934. Robert Blatchford was editor during West’s time on the paper and he found West’s pieces both trenchant and hilarious. And so they are, as we see in a piece entitled “The Mildness of Militancy” about the indefatigable suffrage leader Emmeline Pankhurst and her Women’s Union vandalizing public assets, which was their wont when provoked:

When the Speaker gave his malicious ruling on the Franchise Bill and the corrupt House of Commons accepted it, it was plain that whatever Mrs Pankhurst desired in the way of vengeance would come to pass. Woman suffrage had been strangled by the fat hands of fools and knaves, and it is not the temper of Mrs Pankhurst or her followers to be gentle with fools and knaves. If it had been her will that Mr Asquith should ascend to heaven by the aid of dynamite, many women would have been delighted to arrange the dynamite. I should have been very sorry if they had done so. I dislike the duty imposed on me by the suffrage movement of constantly writing about this least remarkable Yorkshireman who ever lived. But I should dislike still more writing about his corpse. For then I should have to show a decent respect for the dead.

But just as there is no limit to Mrs Pankhurst’s power to command violence, so there is no limit to her clemency. We ought to be grateful to the WSPU for setting an example of good temper and forebearance at a difficult time. It speaks worlds for the benevolence and sanity of the suffrage movement that, stung as it is by treachery, it should punish the country for its disgraceful toleration of Parliament’s villany by such mild disciplinary measures as have been used during the past week. Some of them were of debatable wisdom, it is true. One wonders why active young women should destroy beautiful flowers when the Albert Memorial still stands in Kensington Gardens and there is gunpowder in the land. And the cutting of telegraph wires gives an opportunity for the nepotism characteristic of the Government. Very probably we shall find on the opening of Parliament that all the unemployed members of the Samuels’ and Isaacs’ families (to say nothing of Mr Lloyd George’s private secretaries) have been appointed at salaries of from £800 to £2,000 a year to sit beside telegraph poles, and see that nothing happens. But other forms of militancy could excite no sane person’s serious disapproval. Certainly the destruction of golf greens seems an inadequate revenge on the sluggish nation, but it is one way of approaching people who have entrenched themselves behind petty preoccupations. I love going to music-halls; but if the angels of God coming down to put the hosts of Belial to the sword should by accident knock out the skylight of the Palace, I should not lose my temper. I should feel grateful to them for drawing my attention to the event (particularly it was a really good fight). And similarly the destruction of golf greens is a crude way of calling golfers to higher things.

Exciting times for a young woman with the wit and the pen of the young Rebecca West. She wrote that piece in 1913 at the age of 21. As a means of assessing her progression as an author, let’s have a look now at a paragraph from her masterpiece, Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, published in 1941:

Marmont would have spent all his life in paternal service of Dalmatia had his been the will that determined this phase of history. But he could achieve less and less as time went on, and when he resigned in 1811 the commerce of the country was in ruins, the law courts were paralysed by corruption, the people were stripped to the skin by tax-collectors, and there was no sort of civil liberty. For he was only Marmont, a good and just and sensible man whom no one would call great. But none denied the greatness of Napoleon, who was neither good, nor just, nor sensible.

The later text has the same sharp focus and the same sense of impulsion but its irony is tempered and West’s tongue is not lodged permanently in her cheek. She’s having a good romp in the piece about Pankhurst and the WSPU while at the same time delivering trenchant, indeed mordant criticism of the nation as a pack of sluggards and dimwits. I can imagine Blatchford handing the news of the WSPU actions to West and saying, “Work your magic.” As the voice describing Balkan history she’s still personal but at more of an authorial remove. Her narrative persona has retreated slightly but still shows itself on center stage. We’re still dealing with Rebecca West, no longer young and quite the firebrand she was, but all the same still Rebecca West.

The astonishing thing for me is how consistent the two citations are in authorial register with a distance of 20 years between them. That similarity is all the more astonishing when one considers that the early text was written as a piece of journalism for a newspaper under pressure of a weekly deadline. The citation from Black Lamb and Grey Falcon is the result of a project extending over multiple years, with ample time for West to shape her language in whatever way she thought best for the massive work in progress. The personality behind the words was strong enough to guide them into similar states of expression even across a distance of two decades.

In the matter of authorial register, then, we’re before a phenomenon of extraordinary uniformity over an entire career. West apparently emerged full-grown from the brow of Athena when she picked up a pen to begin writing as a journalist at the ripe age of 18. By the age of 25 she had garnered from no less than George Bernard Shaw acknowledgement that “Rebecca West could handle a pen as brilliantly as ever I could and much more savagely.” To see just how West went about things when she flicked open her stiletto and thrust it in just below the rib cage, let’s look at an excerpt from “Another Book Which Ought Not To Have Been Written,” a review from November, 1913 of The Fraud of Feminism by Belfort Bax:

There is a journalistic curse of Eve. The woman who writes is always given anti-feminist books to review. Thus to earn my keep I have read the fluffy yet resistant matter of Dr Saleeby, and consequently felt as though I had swallowed a feather-bed. I have watched Dr Lionel Tayler’s interminable sentences crawl along like a centipede gone lame in every other foot. I have been enveloped in the fog-like featureless gloom of Sir Almoth Wright. And now I have to diagnose the obstinate case of Mr Belfort Bax, whose fever against women has burst out for the hundredth time in The Fraud of Feminism, which Mr Grant Richards is offering to England for half-a-crown. It is written in ‘the hope that honest, straightforward men who have been bitten by feminist wiles’ — probably a misprint for wives — ‘will take a pause and reconsider their position,’ and it is one of the most distressing books I have yet endured. It is like answering a call on the telephone and hearing no words but distant shrieks and groans and thuds. Woman is doing something dreadful: what is one can’t, from Mr Bax’s disordered sentences rent by intractable commas, quite make out. Like Bishop Welldon, Mr. Bax considers woman a physical failure. It has never broken upon their minds that in valuing a machine one should consider its efficiency rather than its mass or weight. Probably if one went often enough to the British Museum one would find Mr Bax and the Bishop kneeling side by side in silent adoration before the thighbone of a mammoth. Inflamed with pride by the knowledge that their sex holds the record for Indian-club swinging, they term women the weaker vessel. I do not know how they account for their presence among us except by the successful physical efforts of an endless chain of weaker vessels all well up to their job.

Ouch. Too late to staunch the flow of blood now, that stiletto is in there good. In the remainder of the review West methodically demolishes Bax’s arguments, leaving him at the end as one would expect to find a cat got hold of by a pit bull. Serves him right, too, for publishing such twaddle.

It’s important to remember that this is journalism, albeit a book review. In West’s reviews of works of fiction she continues in the same vein with similar results. Having herself published a successful novel in 1918 — The Return of the Soldier — it could be said that West earned the right to critique the work of other novelists. She was certainly hired to do so by a great many newspapers and magazines. But the question remains open whether or not she achieved legitimacy as a literary critic. Some think she didn’t, as Stefan Collini points out in an article from 2008 in The Guardian (here) comparing her critical approach to that of Virginia Woolf, who also wrote both as a journalist and as a novelist:

Although West was 10 years younger than Woolf, the style of her criticism seems closer to the summative, post-prandial manner favoured by the “literary uncles” than to Woolf’s teasing pointillisme. West’s essays rarely contain much quotation or extended analysis of particular passages, of the kind that Eliot and Empson, and later the New Critics, were to make fashionable. Instead, there is broad-brush literary portraiture accompanied by a would-be winning mixture of whimsicality and slash-and-burn destruction. The writing is intensely metaphorical, leaving even her better insights looking a little too self-conscious and showy. In criticising one of Bennett’s books, for example, she writes that it contains “an antithesis between a society woman and a prostitute, which is as wooden and made for a purpose as a clothes-horse”. In complaining about the brute salience of sadness and death in Thomas Hardy’s poetry, she writes: “Really, the thing is prodigious. One of Mr Hardy’s ancestors must have married a weeping willow.” This studied pertness and the echo of a Wildean drawing-room epigram require too much collusive indulgence from the reader: we may remember the phrase, but we learn nothing about Hardy.

I think that’s a fair assessment. If West’s reviews are taken strictly as journalism, which in fact they are, then it’s all good. You don’t expect a review in a newspaper to be like an essay written by a scholar of literature for inclusion in an academic monograph. Seen in that light, West’s literary reviews are insightful and amusing, and part of the fun with any review she wrote is having her dish the dirt, which nobody does better. If you want careful and probing analysis of authorial technique, go to Woolf instead. She beats West hands down in that department.

Of the novels West wrote I can speak from personal experience as a reader. They’re dreadful. The one from 1918 is the best, in my opinion, but would still have been better written as a journalistic essay. Her major work as a novelist, the “semi-autobiographical” Aubrey Trilogy, saw only the first novel of the trilogy completed, The Fountain Overflows. The remaining two novels remained unfinished at West’s death and were published posthumously after being cobbled together by editors. One is tempted in the case of these novels to pilfer West’s own title for her review of Bax’s book: “Another Book Which Ought Not To Have Been Written.” I ploughed my way dutifully through the first volume but repeatedly thought as I read, “You should just have written an autobiography, it would have suited your style so much better.” I did attempt to read the second and third volumes out of curiosity but they stuck in my craw and I started to feel the sick rise, so I stopped.

The Birds Fall Down is the last novel published by West and the only other one of hers I’ve read all the way through. It was for me another instance of astonishment at her choice of subject, a world of Russian émigré aristocrats and political assassinations, based ostensibly in part on the story of Yevno Azef, a Russian double agent who died in 1916. He was a thoroughly disgusting creature who deserved to be forgotten as quickly and as permanently as possible. The plot of West’s novel lurches from one improbability to the next and the dialogue is disfigured by enormously long discourses on Russian history and politics that should have been removed from the book and done as separate essays — pieces of journalism perhaps? — because they have no place in a novel. In other words, the novel fails for precisely the reason that got West into trouble with critics regarding Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, where she puts carefully constructed, elaborate expositions on art, history and politics into the mouths of people who are supposedly having an off-the-cuff conversation, which strains the reader’s credulity well beyond the breaking point.

At the end of the day, then, it seems safe to say that West was a journalist first and foremost. Journalists often write very fine books of nonfiction, one sees that all the time even now, so West’s major accomplishments in that vein make perfect sense for her trajectory as an author. Her mind ranges over the entire course of human history and nothing is beyond her willingness to investigate and analyze. When she takes on a particular subject she doesn’t stop until it’s exhaustively mapped out in her understanding. For that reason Black Lamb and Grey Falcon runs to some 1,200 pages and provides deep insight into things ranging from the history of Byzantine art to the female English eccentrics of the Victorian era who travelled the Balkan countries. It’s all there, woven into a tapestry with the greatest care and craft.

That said, West’s language was formed in the cauldron of the newsroom as the young journalist she was, as were her rapier wit and her ability to coin a memorable phrase. Those things were her stock-in-trade as a budding journalist and they never left her. The line of sight from the early journalism to the monumental nonfiction works of later years is easy to trace. On the other hand her fiction seems to involve an almost separate authorial persona and agenda, one that perhaps reflects the muddle and disjointedness of her private life. Two authors for the price of one, as it were — but I’ll take just the journalist, thanks very much.

Dame Rebecca West (Cicily Isabel Andrews (née Fairfield))

by Walter Bird

bromide print on card mount, 14 February 1964

NPG x165793 © National Portrait Gallery, London

What about the quality of her consciousness? Did her authorial persona develop over the course of her career? Did she somehow become more Westian with age or go through a process of change like many authors do? I think the answer is no, she didn’t. The journalistic Swiss Army knife she had when she started at the age of 18 remained at her fingertips for her entire life. I’d be happy to have half the number of blades in mine West had in hers. If we look only at the fiction West wrote, it’s equally hard to see any development at all. The reason is not far to seek: West wrote novels but was not a novelist, not in the sense that Virginia Woolf or E. M. Forster were novelists. For Woolf and Forster the novel constituted the primary vehicle into which their development as writers and as individuals was channelled. For West novels were a sideline. Her main work was nonfiction. Black Lamb and Grey Falcon proves that point when compared to any of the novels West wrote. It towers like the Empire State Building over the fiction in accomplishment and importance. As for the journalistic oeuvre, I myself don’t see any marked trajectory of development, but I don’t think there was any need for one. If you get kudos from the likes of George Bernard Shaw at the age of 25, you’re well advised just to keep doing what you’re doing. It looks to me like West did exactly that.

In Black Lamb and Grey Falcon, as I mentioned above, West gives a synopsis of her career that puts a fine point on the matter. While in Vienna on the return trip from Yugoslavia West was interviewed by a university student of literature, a young woman, who had decided to write her thesis on West’s works. West’s reaction was as follows:

I was naturally appalled. I explained that I was a writer wholly unsuitable for her purpose: that the bulk of my writing was scattered through American and English periodicals; that I had never used my writing to make a continuous disclosure of my own personality to others, but to discover for my own edification what I knew about various subjects which I found to be important to me; and that in consequence I had written a novel about London to find out why I loved it, a life of St. Augustine to find out why every phrase I read of his sounds in my ears like the sentence of my doom and the doom of my age, and a novel about rich people to find out why they seemed to me as dangerous as wild boars and pythons, and that consideration of these might severally play a part in theses on London or St. Augustine or the rich, but could not fuse to make a picture of me as a writer, since the interstices were too wide.

Fair enough, and straight from the horse’s mouth. On the basis of my own reading of West’s works, however, I would offer the following point in objection. In 1912, when West was 20 years old, she published in The Freewoman a review of a play by Harley Granville-Barker (info here). It’s a good review, quite thorough, at the end of which comes a statement that hit me like a bolt of lightning when I first read it:

… Perhaps if Barker returned to the manner of Ann Leete, in which he speaks with a vivid dramatic idiom he has since obscured by echoes of Shaw and the Fabian Society, he might suggest some other way to freedom. As it is, he has given us a strong hatred, the best lamp to bear in our hands as we go over the dark places in life, cutting away the dead things men tell us to revere.

” … cutting away the dead things men tell us to revere.” It would be astonishing enough had West produced that phrase when she was in her maturity, but for something of the sort to come from the pen of a 20-year-old boggles my mind. In that phrase I find West’s entire authorial agenda, which I think can be traced through the long years of her career. She remained to the end of her days the pit bull chasing after the humbug that clutters up life in order to cut it away and reveal the naked truth. That authorial intent forms the thread that binds her nonfiction works together, in my opinion. The interstices may be wide between the genres in which she wrote, that point I concede, but when I go to read West’s nonfiction work I always find the same person operating on that same agenda, regardless of the topic that happens to be under her knife.

Only in her early work does one find the root of that trajectory, I think. And to be perfectly honest, it’s to the early work I return most often because West’s star shines there most brightly. The world was new to her, her mind was at its sharpest, social structures were cut and dried and it was easy to identify the cats to chase — opponents of votes for women, for example, or the fuddy-duddies of the Victorian and Edwardian literary establishment. The early work shows West in continuous Ninja mode, a linguistic Charlie’s Angel doing backflips off high walls to land directly in front of her foes and deliver the stiletto thrust that will take them out. In modern parlance: cowabunga, dude.

So all hats off to the young Rebecca West. We’ll not see the like of her anytime soon. What a pity, we could use some pit bulls of her ilk these days. At our distance of a century, however, we can appreciate her bark even though we can’t any longer count on her to bite the bad guys. The bad guys should feel lucky, because if the young Rebecca West were still with us the fur would be flying in every direction.