March 2020

In the interests of transparency I must confess that I’ve avoided 19th and 20th century opera literature like the plague over the course of my lifetime to the point that my negligence could be said to have moved into the precincts of prejudice. In the past few weeks, however, I’ve attempted to reassess the literature for the sake of a few voices whose brilliance and accomplishment demand admiration regardless what music they sing. I’m thinking about Lucia Popp primarily, but there are a few others who fall into that category — Rita Streich is one and Agnes Baltsa is another. So what I’ve done is focus on one bel canto aria that every coloratura soprano and her dog sings: “Una voce poco fa” from Il Barbiere di Siviglia by Rossini.

In the interests of transparency I must confess that I’ve avoided 19th and 20th century opera literature like the plague over the course of my lifetime to the point that my negligence could be said to have moved into the precincts of prejudice. In the past few weeks, however, I’ve attempted to reassess the literature for the sake of a few voices whose brilliance and accomplishment demand admiration regardless what music they sing. I’m thinking about Lucia Popp primarily, but there are a few others who fall into that category — Rita Streich is one and Agnes Baltsa is another. So what I’ve done is focus on one bel canto aria that every coloratura soprano and her dog sings: “Una voce poco fa” from Il Barbiere di Siviglia by Rossini.

It was only after doing research on the aria that the title for the post came to me — since we’re back once again in Wench Land. Why things must always be about wenches and their wags passeth understanding, but there it is. I pretend I don’t understand Italian when I listen to opera because the stories are so bloody stupid they make me wanna puke on my shoes. The only way to get through things is to put the cognitive equivalent of soundproofing for Italian into your ear canals. Usually the diction gets lost in the vocal acrobatics anyway, so it’s not very hard to do. Thank goodness, otherwise I’d find myself thinking, “WTF?? Are you SERIOUS???” So yes, we’ve got another strumpet on our hands and she’s carrying on like a trumpet, belting it out like a brass band. I laughed out loud when I came across a recording of trumpeter Maurice Andre playing the aria on his golden horn. What’s sauce for the strumpet is obviously sauce for the trumpet, so the evidence proves. The irony was too delicious not to savor.

I was dumbfounded to discover that the aria is a cavatina. Say “cavatina” and I immediately think of something slow and fairly quiet with the emphasis on lush melody, not on vocal acrobatics. Just goes to show how little I know. Subsequent research revealed that the cavatina, like most things in life, is more complicated than it appears at first inspection. Here’s the skinny from the Wikipedia page on the beast (here):

Cavatina (Italian diminutive of cavata, the producing of tone from an instrument, plural cavatine) is a musical term, originally meaning a short song of simple character, without a second strain or any repetition of the air. It is now frequently applied to any simple, melodious air, as distinguished from brilliant arias or recitatives, many of which are part of a larger movement or scena in oratorio or opera.

One famous cavatina is the 5th movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in B-flat major, Opus 130. “Ecco, ridente in cielo” from Gioachino Rossini’s opera Il Barbiere di Siviglia, “Porgi amor” and “Se vuol ballare” from Mozart’s The Marriage of Figaro are also well-known cavatinas.

…

In opera, the term has been described as:

a musical form appearing in operas and occasionally in cantatas and instrumental music….In opera the cavatina is an aria, generally of brilliant character, sung in one or two sections without repeats. It developed in the mid-18th century, coincident with the decline of the previously favoured da capo aria (in which the musical form is ABA, with the repeated A section given improvised variations). Examples occur in the operas of Mozart, Weber, and Rossini. In 19th-century bel canto operas of Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi the term came to refer to a principal singer’s opening aria, whether in one movement or paired with a contrasting cabaletta.

No wonder I was confused. In fact, I think I still am … But I see now that my sense of the word is decidedly 18th century. I never got the bel canto memo on the cavatina form, sorry to report, but I’ve updated myself and we’re now on the right page to discuss Rossini’s warhorse of an aria. Let’s not put it off a moment longer. 🙂

Do you realize it’s in E major? Go figure. What’s the matter with C or D major? But I’m going off on one of my rants, the kind that starts when I see 19th century piano music with five or six flats in the key signature. Coming from the Baroque as I do, that many flats or sharps just means that you’re being willfully difficult or that you smoked some kind of controlled substance before you put pen to paper. There’s no reason on God’s green earth for more than three sharps or flats in a key signature, even if you feel like pushing the boat out. With Signor Rossini, however, we are both in the bel canto and in the 19th century so I’ll stifle myself about the key signature. It could be worse, as folk made abundantly clear some few decades after Rossini’s day (yeah, we’re lookin’ at YOU, Mr. Chopin …). Research revealed that it’s often transposed to F major so the soprano can go even higher into the stratosphere with the vocal fireworks. Hey, if you can wangle a chance to pop out an F6, that primo money note, why not? Go for it! It pays the bills, babes, and don’t you forget it. You think you’re gonna pay off that condo on the Viennese Ringstrasse staying in chest register? Think again, bucko.

Another concept that needs to be stretched to the breaking point is the notion of being “through-composed.” After listening to several recordings of the aria and noticing the enormous variety on evidence with regard to tempi and coloratura improv, I decided I’d better have a look at the score to see what Rossini put down on paper. A piano reduction does the trick quite well, no need for the full orchestra score. Well, a quick glance over the business to hand on the page showed me there’s a good reason things seem to go in fits and starts.

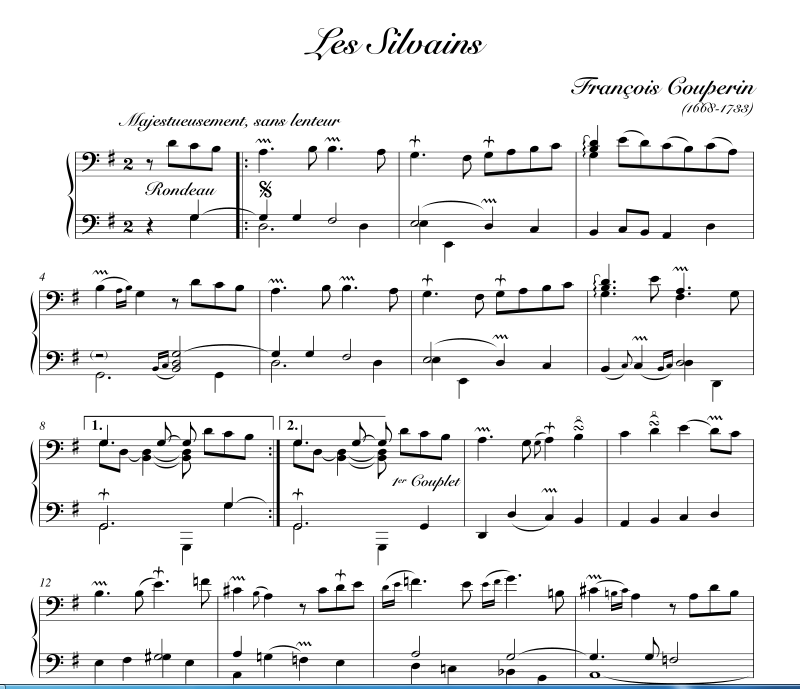

For someone steeped in 18th century French keyboard music the experience of a Rossini score is almost psychedelic. An 18th century French keyboard composer — Couperin, for example — will tell you exactly what he wants done and when he wants it done as one sees clearly in something like, say, Les Silvains from Book 1 of the Pièces de clavecin. If you do any improvising mommy will spank. It’s that simple. Every ornamentation sign over every note is accounted for in Couperin’s table of explanations about just how to render the signs. So there will be no wanton jumps up to F6 just for the sake of showing off your chops, thank you very much. Where do you think we are, anyway, in a trailer park???

It’s clear that Rossini’s approach to things couldn’t be more different. As I listened to recordings of the aria it became clear to me that in the case of some the piece failed to hold together as anything that could reasonably be called “through-composed.” There were snippets of melody — quite nice melody, truth be told — and then the proceedings would grind to a halt while the soprano went all coloratura on us. That goes far, far beyond anything I’d be willing to call rubato — which in Italian means “robbed,” since you steal a bit of time from the notes you’re bending. Some performances of our warhorse aria are so chopped up they become comprehensible only as showcases for vocal bravura. The musical flow is subject to such continual interruption you can’t follow a melody beyond a few bars before it’s time for the soprano to go nuts once again and lose whatever thread of a tune you had between your fingers. Harumph.

Looking at Rossini’s score leads me to believe that if a conductor (and a coloratura soprano) decided to go the bravura route and leave the melody bit in the dust, the composer would likely say, “Whatever.” He’s built enough gaps into the score to allow the soprano to go crazy with the acrobatics. From a harmonic standpoint there’s a good bit of sitting on one’s haunches — hunkering down on a dominant, for example, until Miss Thang finishes her warbling. But it doesn’t have to be that way. If you keep things moving along then it all hangs together melodically perfectly well. That point becomes evident when you compare Rossini’s original notation to the manic fioritura notated in smaller notes on the two staves above Rossini’s original in the example below. When I see the hoopla the fioritura charts out I think, “Looks like it’s time for one of your tablets, dear heart …” Rossini did not put fermatas over the orchestra parts on the first beat of the measures, which leads me to believe it wasn’t his plan to have the soprano spend five minutes going batsh*t over the other two beats of each measure. But hey, it happens. Give ’em an inch etc. etc.

Part of the impetus to explore this literature came, as I mentioned, from my glowing admiration for the Slovak soprano Lucia Popp (info here). I came across a recording on YouTube (here) of a performance she did of the Rossini aria on a German television show (that looks regrettably like a Teutonic analogue of The Lawrence Welk Show, but let’s not think about that, OK? 🙂 ). I’ve always thought her rendition of the Mozart aria “Der Hölle Rache kocht in meinem Herzen” (aka the “Queen of the Night Aria”) from The Magic Flute to be among the very best on the books. After digging around in the YouTube bin a bit more I found a recording of her performance of Richard Strauss’s Vier Letzte Lieder (= Four Last Songs). I have the recording made by Gundula Janowitz in my collection and have always considered that the go-to version, but Popp’s rendition is fully the equal of Janowitz’s, a fact which didn’t surprise me at all as I listened to it. Popp’s voice is as smooth as spun silk but has depth and power in all registers, just like Janowitz’s. There’s a wistfulness and sense of reserve in Popp’s musical beingness that suits the Hesse poems used in the Vier Letzte Lieder even better than the more stentorian quality Janowitz has.

So I decided to take Popp’s recording of the Rossini aria as my baseline and go crazy listening to all the performances of it I could find. If you search “una voce poco fa” on YouTube you’ll be presented with a colossal embarrassment of riches. As I said, every coloratura soprano and her dog has done the thing. As my research continued I realized that things could become very complicated, indeed. The term “coloratura soprano” has all kinds of subcategories I knew absolutely nothing about. What, for example, might a soprano acuto sfogato be? On first showing the phrase looks to me like something you might find in the wing of an airplane and want not to lose after taking off from the runway. As in: kathunk. OMG we just lost the left acuto sfogato!! We’re all gonna DIE!!!

The bel canto literature attracts coloratura sopranos and mezzo-sopranos like picnics attract ants and you can find them gathered around it like gazelles at a watering hole. It doesn’t seem to matter what their respective fach might be — lyric coloratura, soprano spinto, soprano acuto sfogato, they all show up at the Rossini bar and slap down their cash on karaoke night. As I explored recordings of the aria it became clear to me that the nature of the soprano had a great deal to do with the choice of approach to the performance. Popp’s televised performance, for example, is a concert setting, not from a staged opera, so she stands elegantly clad and sings with her usual poise and grace. She was a lyric soprano among the best but her reputation in the first part of her career was earned for her coloratura capabilities, especially in the role of the Queen of the Night. Her performance of the Rossini aria has its high notes but they don’t disfigure the musical proceedings to the point of making the melody hard to follow. All is ease and elegance with Popp.

But that’s not the way everyone does it. I found the following explanation (full text here) helpful in sorting things out concerning what kind of soprano could be expected to go crazy and warble the melody to smithereens:

The Acuto Sfogato

By Nicholas E. Limansky & John Carroll

One of opera’s great universal attractions is the ability of the human ear to be thrilled by the trained human voice at its highest frequencies — in other words, high notes. The highest of the high is the realm of the coloratura soprano, and for this reason they are controversial — either fanatically beloved or condescendingly disparaged. High F has always been considered the Holy Grail of high notes for sopranos. A documentary made about the young German coloratura soprano Eva Lind was titled in all seriousness: “The Search for the High F”. It is the highest note required in a role that is in the standard repertoire: the Queen of the Night in Mozart’s Die Zauberflote. There are a total of five staccato high Fs in her two arias. Of course, it is always judicious to note that in Mozart’s day the standard pitch was about a 1/2 step lower than it is now (over the years violinists have slowly raised it in order to provide a more brilliant sound to their instruments, much to the chagrin of vocalists of all fachs, so the Queen of the Night’s high Fs in Mozart’s day would be equivalent to our present day high Es. Even more confusing, the concert pitch in Europe is slightly higher than it is in America.) Some legendary coloratura sopranos didn’t have a reliable high F — Maria Callas, Joan Sutherland, and Beverly Sills to name just three superstars of the mid-20th Century. “How high is high F?” Sills ponders in her autobiography, “VERY high”. Sills felt her batting average for the Queen of the Night, a role she didn’t like but sang internationally for a few years, was four out of five, and she considered that pretty good. For a while there was a pointless debate as to whether Maria Callas sang a high F in public (Rossini’s Armida). An examination of the score of Armida, however, proves that the ensemble being discussed was composed in the key of E not F- major. Dame Joan Sutherland’s Fs were extremely rare — she took them for an indisposed Naida Labay in Der Schauspieldirektor at Glyndebourne — and recorded high F just once– in her early studio rendition of “O zittre nicht” (again, the Queen of the Night). When she sang the role on stage at Covent Garden, the two arias were lowered. Even mezzo sopranos obviously consider this an important note as witness comments made by dramatic mezzo Dolora Zajick in Opera News that she has a working range to the high F. High F has become some sort of be-all and end-all. We are going to concentrate on sopranos who were able to not only sing high F, but notes above it in “altissimo” (commonly referred to as in alt.). The term “in alt.” refers to the octave above the treble staff from the G just on top of it to the F a seventh higher — the high G over that high F is altissimo. The voice type known as the soprano acuto sfogato, translated loosely as “extreme without constraints,” is the voice that has an extension into the altissimo area. Some pedagogues refer to these extreme high notes as the female falsetto, whistle notes, pipe-tones or the third octave. Emma Calve learned a secret technique from the castrato Mustafa that she called her “fourth voice” (although this only took her to the E in alt). It seems most probable that this was basically a version of a “humming” technique that has also been used by such artists as Lily Pons and Yma Sumac. Even if produced by a healthy, legitimate technique, the cultivation of altissimo notes can throw a singer’s registers out of balance so that the lower vocal compass becomes weak and often fullness of tone in the middle voice is also sacrificed. Generally, therefore, the acuto sfogati are confined to the soprano leggiero repertoire and only a few are capable of effectively singing lyric and soubrette roles. But it is a price many women have paid (or will pay) as there was a time when a soprano could build a career dazzling the public with these money notes. What causes such unusual voices? Many believe that these extra top notes are left over from the pre-adolescent female child’s voice before the vocal cords lengthen during puberty. This would account for the often child-like, or “little girl” timbre some of these singers exhibit in their middle and lower registers. Conversely, some, such as Natalie Dessay, have apparently no differentiation in sound between the lower and top registers. Even with this non-lengthening of the vocal cords, much cultivation and careful training is necessary to perfect altissimo emission and technique. Having such notes does not automatically guarantee their use in public. (Many sopranos can sing high G, A or B above high C while practicing but that does not mean they would exhibit such notes in public.) In truth, the acuto sfogato voice type has all but disappeared in modern times. This is partially due to the ever increasing size of performance halls and orchestras. Only large voices can project over all those instruments in our cavernous opera houses, so student voices are developed for size over agility and range; even small coloratura voices are encouraged to fatten up their sound. This has led to (or coincided with) a waning of the public’s taste for bravura showpieces that were the specialty of the high coloratura soprano. Another reason for recent decline of the acuto sfogato is the “come scritto” movement that treats a composer’s score as a sacred text and demands it be sung only as written. With a few significant exceptions, most extreme high notes were not written by composers into their scores. Even so, because a composer did not write a high note into the vocal line does not mean that he didn’t want or expect one there; certain baroque, classical and bel canto arias have a performance traditions that allow for and even encourage such departures. Most of these traditions stem from the time the works were being performed with the composer still alive and assuredly aware of what was being done to his score. But in the academic come scritto ethic, any interpolated high note or embellishment is condemned not just as bad taste but as profoundly disrespectful. Critical distaste for extravagant altissimo wonders is not strictly a modern occurrence. In 1851, Henry Chorley wrote about these highest soprani: “The feat, when it is done, is worth little and it may be counterfeited by adroit trickery. If the feat, however, be not elegantly mastered, the effect is more than worthless — one to recall the pain of a surgical operation, howsoever it may strike the vulgar with surprise.”

There’s an interesting documentary on Joan Sutherland called Joan Sutherland, the Reluctant Prima Donna (available on YouTube here) that chronicles her breakthrough in the bel canto literature with Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor. She started a trend and soon sopranos all over the place were trilling and doing staccato arpeggios and whatnot. Eventually the acuto sfogato found its way back into the scheme of things in such works. If we take Lucia Popp as our lyric coloratura baseline, then at the acuto sfogato end of things we must take the incomparable Ingeborg Hallstein as our touchpoint. Her performance of Rossini’s aria is available on YouTube here, with the title “Ingeborg Hallstein dances her Rosina up in the Stratosphere.” Trust me, they’re not just whistling Dixie on that point.

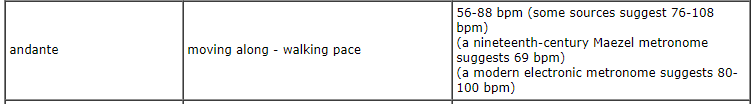

What are the differences between the renditions by Popp and Hallstein? First and foremost is tempo. Rossini’s tempo indication is andante — which means “walking” in Italian. Just how fast or slow is andante supposed to be? Here’s one indication (website here):

Popp’s rendition is what I’d call a true andante — strolling along as she does, even with the fioritura into the bargain, the sense of movement in the melodic line is never lost. The orchestral writing is such that any big slowdowns in the vocal part to go nuts with the fioritura makes the orchestra sound like it’s starting back up from a dead stop if the gaps are too wide between entries. In some recordings I heard it wouldn’t surprise me to learn that a poker game had started up in the second violins — they probably post the first flautist to keep an eye on things so they know when it’s time to put down the cards and pick up the instruments again. There’s never that sense in Popp’s rendition of the orchestral proceedings grinding to a dead halt. In other words, the fioritura — the vocal fireworks — never becomes the main focus. The melody remains the center of attention. After all, it’s an aria in an opera, not a sheet of vocal exercises for learning how to become a coloratura diva.

Then we come to Hallstein’s version. Had I been streetwise in matters operatic I’d have seen the musical red flags go up with the first bar of the orchestral introduction because the tempo is as slow as molasses in January. But I was still an acuto sfogato virgin when I first heard Hallstein’s performance, thus I was led unsuspecting like a lamb to the fioritura slaughter. Mind you, the woman nails it, and how. Nobody can complain about the vocal performance from the standpoint of brilliance. Hallstein is IMHO at the top of the acuto sfogato heap. And she’s no dummy. She has lots of recordings available on YouTube so you can hear her in all kinds of roles. She tweets as easily as birds in spring, sailing effortlessly up into the stratosphere, always hitting the bullseye. But she was also quite good at singing Lieder and you can’t do that if you’re a bird-brain. She earned her spurs in a number of different roles, including a Musetta in La bohème done early in her career where she’s definitely a strumpet with a trumpet and 100% the kind of girl mothers rightly warn their sons about.

I suppose when you have high-range chops like Hallstein’s it’s a foregone conclusion that when you come to the bel canto literature you’re going for the fioritura fireworks. Knowing what I know now, when I hear the opening bars of the orchestra in Hallstein’s version of Rossini’s aria I take the cue to settle back and wait for the fireworks to start. That’s the whole point. There’s no use trying to follow the melody or to fit the harmonic progression into a recognizable pattern. You’re there to witness an astonishing feat of vocal acrobatics, not to follow a melody, mate. And that’s exactly what happens — we are astonished by the incomparable vocal display. If, however, you try to hum the melody to yourself after the aria ends you’ll immediately falter and say to yourself, “How does that go again??”

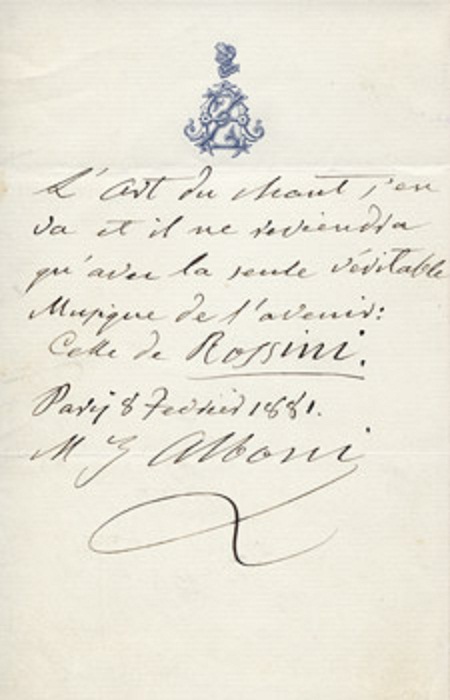

What would things have been like in Rossini’s own day? A quick look at his biography shows that sopranos consistently occupied his attentions — off the opera stage as well as on it. He apparently had affairs with two coloratura sopranos before he finally settled down and married one, Isabella Colbran, in 1822 — six years after writing Il Barbiere di Siviglia. She was a Big Deal and sang Rossini’s works to better effect than anybody, so said Rossini himself. Here’s a tidbit from her Wikipedia page (here):

Descriptions of Colbran’s voice characterise the timbre as “sweet, mellow” with a rich middle register. Rossini’s music for her suggests perfect mastery of trills, half-trills, staccato, legato, ascending and descending scales, and octave leaps. Her vocal range extended from F-sharp below the staff to E above, with a high F sometimes available.

Obviously not an acuto sfogato like Hallstein — much more in the Popp vein. But when one considers the matter it becomes clear that the coloratura soprano of the early Classical era replaced the castrato of the 18th century as the showstopper soprano voice. Since it apparently became bad form to emasculate young boys so they would retain their soprano voices into adulthood, women had to jump into the gap and take over the job. If you were staging operas in the 18th or early 19th centuries, the showstopper voice was a must-have — just think of the Italian castrati, their immense fame and the fabulous wealth they gained in their careers. Castrati were all about fioritura, so it’s only logical to assume that the role of the showstopper coloratura soprano in Rossini’s day was similar. That would militate for the Hallstein approach rather than the Popp agenda.

For someone like myself who stands entirely outside the taste for operatic literature of the 19th and 20th centuries, the Hallstein approach is one element that held me at arm’s length from the repertoire. If you consider the usual objections to operatic singing by the uninitated and unenlightened — that it’s caterwauling, in essence — the reasons are not far to seek. Such objections are usually to music coming from later Grand Opera repertoire but if the bel canto repertoire were substituted the objections would remain although the specific complaints might change. One of the most common objections to Baroque music I hear is, “There’s no melody and it doesn’t have a beat.” Which means it doesn’t have something you can sing along with or wiggle about to on a dance floor. The objections to bel canto literature would be much the same, I think — no melody and no beat. The melody gets lost in the fioritura and the beat goes missing due to the grinding halts made so the soprano can go nuts. It’s sort of like going for a walk with somebody who’s gone off their meds: lots of stops while crazy stuff happens.

As I mentioned, I’d listen to Lucia Popp no matter what she’s singing because of the beauty and humanity of her voice. She communicates a beingness when she sings, not just a melody, as great writers do with their words, and that’s what keeps me at her feet in admiration. As for the bel canto literature, it’s clear it has lost forever whatever special position in the musical firmament it had in its own heyday. It now gets slotted into something like Wagner-lite if it’s glum (e.g. Lucia di Lammermoor), ersatz operetta if it’s cheery (e.g. La fille du régiment), or it simply becomes the Vocal Olympics. Historically speaking I suspect the Vocal Olympics slot is closest to the reality of the early 19th century. If that was indeed the case, then I’d have spent none of my hard-earned cash on opera tickets, just as I have purchased zero — count ’em, ZERO — recordings of bel canto operas for my collection.

The main takeaway from my exploration of the bel canto coloratura literature is great admiration for the accomplishment of the women who sing it. Ingeborg Hallstein, for example, is flat-out amazing. We are justly gobsmacked when such a voice enters our ears. Likewise, when Lucia Popp sings, humanity somehow makes more sense than it did before. That’s a gift I always receive from her with deep gratitude.

As for bel canto warblings in and of themselves, well … it’s art, isn’t it, so inevitably we end up back at de gustibus non est disputandem, or chacun à son goût, which is to say: to each his own. If somebody gets all tingly up and down the spine when hearing bel canto coloratura arias, then dadgummit, go for it.

It’s all good. 🙂