February 2019

In my young days I toyed with the idea of becoming a professional musician. It didn’t take long before I realized that was a bad idea if I wanted to make a living because I was an outlier in the musical scene, not somebody with a posh office in the downtown business district. I studied early music and specialized in the harpsichord. Since the majority of people I encountered in the USA at that time had no idea what a harpsichord even was, it didn’t bode well for becoming rich and famous on the fast track. I decided that discretion was the better part of valor and turned my hand to something else to make sure that ends met on a regular basis. The desire to make music continued, however, and has never left me. How could it be otherwise? I’m a musician through and through, although it’s now been a good many years since I played ensemble music or performed publicly. Even if I never again play another note I’ll still consider myself a musician. That’s just how it works when you’re to that manor born.

In my young days I toyed with the idea of becoming a professional musician. It didn’t take long before I realized that was a bad idea if I wanted to make a living because I was an outlier in the musical scene, not somebody with a posh office in the downtown business district. I studied early music and specialized in the harpsichord. Since the majority of people I encountered in the USA at that time had no idea what a harpsichord even was, it didn’t bode well for becoming rich and famous on the fast track. I decided that discretion was the better part of valor and turned my hand to something else to make sure that ends met on a regular basis. The desire to make music continued, however, and has never left me. How could it be otherwise? I’m a musician through and through, although it’s now been a good many years since I played ensemble music or performed publicly. Even if I never again play another note I’ll still consider myself a musician. That’s just how it works when you’re to that manor born.

To do early music in the United States you have to be near a population center that has other folks with the same interest. Out in the sticks you’re on your own, there’s no way around that fact. When I was in my mid-40’s I got so sick of living in big cities that I decided to abandon them once and for all. With that decision early music ensemble playing went largely out the window. I knew it would, but oh well … you pays your money and you takes your chances. I’d had my fill of amateur groups by that point, anyway. Yes, there’s a story to tell, and tell it I shall. Spendors and miseries of the amateur musician, where to begin …

I started out in the sticks, in point of fact, not in the urban thick of things. Where I grew up interest in classical music from any century at all was completely anomalous. But I was for some unaccountable reason predisposed. I remember very clearly when I discovered Baroque music. I was about twelve and heard at school a recording of the first movement of the second Brandenburg Concerto by You Know Who. It’s a great piece and I still love it, although I hardly listen to Bach. Its effect on me was electrifying. I remember thinking to myself, “That’s my kind of music.” And so it has been for nigh on 50 years now. My devotion to music composed before 1800 has remained as constant as the daily rising and setting of the sun. It will last until death do us part, I’m sure.

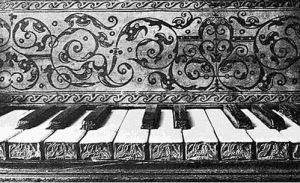

As a teenager I built both a clavichord and a virginals from Zuckermann kits (info here). Such excitement! I’d have loved to build the big French double kit but I didn’t have the moolah. I stumbled my way through the early keyboard literature — including Scarlatti sonatas, which shows just how musically foolhardy I was — to the point that when my grandmother visited she begged that I cease and desist LOL. Can’t say I blame her, if I heard myself now I’d likely do the same. In those days there were great budget record labels like Nonesuch that allowed me to discover all sorts of wonderful Baroque gems. An example of recordings I loved particularly is one of the Symphoniae  Sacrae (op. 6) by Heinrich Schütz, especially “Fili mi Absalom” for bass solo with a choir of trombones. Fantastic stuff — with music like that I felt no need for Puccini. Organ music was at the top of my favorite list and I remember fondly a boxed set of Buxtehude’s complete works played by Walter Kraft on the (modern) organ in Buxtehude’s own Marienkirche in Lübeck. A special favorite I discovered later was a recording of the complete organ works of Brahms played by Kurt Rapf on the organ of the Ursulinenkloster in Vienna. To this day I’ve never heard a better recording of those works, especially the eleven chorale preludes of op. 122. What a pity the recording is unavailable now except as an LP through Ebay — and who has a turntable these days except extremophile retro types? I ditched my LPs long years ago. Here’s a pic of the organ:

Sacrae (op. 6) by Heinrich Schütz, especially “Fili mi Absalom” for bass solo with a choir of trombones. Fantastic stuff — with music like that I felt no need for Puccini. Organ music was at the top of my favorite list and I remember fondly a boxed set of Buxtehude’s complete works played by Walter Kraft on the (modern) organ in Buxtehude’s own Marienkirche in Lübeck. A special favorite I discovered later was a recording of the complete organ works of Brahms played by Kurt Rapf on the organ of the Ursulinenkloster in Vienna. To this day I’ve never heard a better recording of those works, especially the eleven chorale preludes of op. 122. What a pity the recording is unavailable now except as an LP through Ebay — and who has a turntable these days except extremophile retro types? I ditched my LPs long years ago. Here’s a pic of the organ:

As a rube from the sticks I had no idea what being a professional musician really involved. I knew professional musicians played music all the time but I was ignorant about the social reality of professional musicianship, especially as it’s conducted in the United States. It’s a tough row to hoe, as anyone in the know will confirm, and I quickly found out that I utterly lacked the desire to engage its social aspects — the schmoozing with wealthy and often tone-deaf patrons, the competition and self-promotion, in short: all the non-musical things necessary to make a music career work. So I ditched the idea of becoming a career musician and went into something else geared to make me a living without driving me completely crazy. I did pretty well as far as making a living goes, but the jury’s still out on the crazy part. 🙂

So off I went at a tender age into my uncertain musical future shunted forevermore into the Mirkwood of amateur musicianship. I had good company, as I discovered over the years. The comedian Phyllis Diller (I’m dating myself here, I know, but I’m well past the expiration date anyhoo) shocked the public by revealing herself to be a pianist of professional-level accomplishment. I remember seeing her on a talk show — Merv Griffin? Phil Donahue? it escapes me at the moment — where she yukked it up and then sat down at a grand piano and whipped off to perfection one of Mendelssohn’s Lieder ohne Worte. There’s an excellent article (here) on the role pianism played in her career. She could have become the female Victor Borge but steered clear of that gig, choosing to stick just to comedy. Hugh Laurie, who’s now a household name both in the UK and in the USA, is another celebrity with a musical secret — he’s a fine jazz musician with two albums to his credit (an article from The Telegraph is here). Whoda thunkit.

The number of people who actually make a decent living doing early music is miniscule. When I look at the recordings I have I see the names of the same European ensembles and soloists over and over again. If only a handful of people can make a go of it in Europe, then you can reduce that number by about 75% for the USA. I have yet to come across any celebrity who gets outed as a harpsichorist, gambist or Baroque flautist. Early music is still a minority presence in the scheme of things even at the best of times.

In my younger days the early music scene in the USA was still in its infancy. Even in large cities there was very little going on in the way of early music performance at the professional level. Amateur connections were also few and far between and almost always involved instrumentalists, I never met any singers interested primarily in literature before 1800. So as an amateur one took one’s chances with whatever folk were available. As you can imagine, that road was not without its potholes.

I should say at this juncture that I studied performance practice to the point that I could perform at professional level but never got the academic credentials to go with the performance studies. My music theory is weak, that must be said, although my music history is robust and I can read musicology scholarship in five languages. It’s easier to reach that stage of development in early music because it has much less of what I call the “Ascended Master Syndrome.” If you intend to make a splash as a concert pianist, violinist or conductor you have to study with an Ascended Master so you, too, can ascend Parnassus and get the big bucks. Without that Grade A seal of approval you’ll get nowhere. In my younger days the early music scene was still too new to have much of that going on, although it was beginning.

I should say at this juncture that I studied performance practice to the point that I could perform at professional level but never got the academic credentials to go with the performance studies. My music theory is weak, that must be said, although my music history is robust and I can read musicology scholarship in five languages. It’s easier to reach that stage of development in early music because it has much less of what I call the “Ascended Master Syndrome.” If you intend to make a splash as a concert pianist, violinist or conductor you have to study with an Ascended Master so you, too, can ascend Parnassus and get the big bucks. Without that Grade A seal of approval you’ll get nowhere. In my younger days the early music scene was still too new to have much of that going on, although it was beginning.

For harpsichordists of the historical performance practice ilk the Ascended Master was Gustav Leonhardt. Alan Curtis, an American, was another name, more ascended on the U.S. side of the Atlantic than on the European side, however. My harpsichord teacher had studied with both people, but he was stuck out in the Pacific Northwest so there was small chance he would himself ascend to such exalted ranks. The only Americans I know who approached that level ended up getting academic positions in Europe, from which base they entered the European scene and did their best to deflect awareness from their American origins. I suspect that these days the Ascended Master Syndrome is full-blown in early music, as well — it seems to be the way humans like to organize things, more’s the pity. It never made much sense to me. Only the music mattered.

So in the interests of full disclosure I state for the record that I’ve never been given a light sabre by some musicological Yoda. Since I’m not a professional that means I’m an amateur — those are the two categories available. The term “amateur” in current usage has a negative semantic envelope, unfortunately. I’ve never applied it to myself. I studied too long and too intensively to be considered an amateur in the sense the word usually has in general parlance. But inevitably, the way society organizes life comes to bear on how one is perceived. Without a light sabre emblazoned with my master’s name I couldn’t possibly expect to be taken seriously as a musical Jedi by anybody who has one. That’s just how it works, whether you have the chops to play the good stuff or not. Not my idea, but there it is. Nobody said life has to make sense, right?

Finding myself thus relegated to Amateur Land, I made the rounds as one does. I wouldn’t dream of putting either you or myself through a blow-by-blow recounting of what I experienced. The best approach is probably to classify the experiences by type, since they fell into patterns, as does most human experience. Let me describe the context types I encountered and see if they ring any bells.

![]()

The Soccer Mom Recorder Group

If you’re in the amateur early music scene, sooner rather than later you’ll come across this kind of group. The people in it are most often soccer moms on the upper end of the middle-class spectrum. There might well be a few academics in the mix, too — maybe a physics professor with a penchant for playing music once in a while. They all play recorders and usually have nice instruments because the spouse probably pulls down six figures. Moeck instruments (info here) are the standard, unless you have somebody with tons of money or excessive pretensions who buys a von Heune (here) or the like, but that’s fairly rare. Almost always it’s Moeck because they’re the standard item in the marketplace for somebody who isn’t going after a spendy professional instrument.

If you’re in the amateur early music scene, sooner rather than later you’ll come across this kind of group. The people in it are most often soccer moms on the upper end of the middle-class spectrum. There might well be a few academics in the mix, too — maybe a physics professor with a penchant for playing music once in a while. They all play recorders and usually have nice instruments because the spouse probably pulls down six figures. Moeck instruments (info here) are the standard, unless you have somebody with tons of money or excessive pretensions who buys a von Heune (here) or the like, but that’s fairly rare. Almost always it’s Moeck because they’re the standard item in the marketplace for somebody who isn’t going after a spendy professional instrument.

The group will usually meet once a month during the school year and of course it’s the perfect occasion for a dessert buffet after the music-making. Summers are for the kiddies, so the group is usually either on hold or meets irregularly during the months school is out. As for the music-making, well … if you play once a month and aren’t very good to begin with, it takes no great powers of insight to predict that there will be few eruptions of genius. This category of amateur group was the first type I ditched because I simply couldn’t stand it anymore. Plowing through some arrangement for recorders of a Renaissance vocal motet with stops every three bars because Janice lost her place again … oh dear, I’d rather have a root canal. So it wasn’t long before I decided that even if the dessert buffet was fabulous (and it usually was) the pain of the music-making made it not worth the trouble. I can get cheesecake elsewhere, thanks very much.

The College Student Group

There are colleges everywhere and if you’re an amateur who plays an unusual instrument — at the time I was on the scene Baroque flute and viola da gamba qualified as such — then occasionally you can be offered the opportunity to do some playing with college students. I always accepted such opportunities with an open mind and was always happy to share what I knew about Baroque performance practice. Was the music-making good? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. It’s a variable feast and requires low expectations with a lot of patience. I remember being brought onboard to do a couple of the Bach sonatas for violin and obbligato harpsichord (BWV 1014-1019), met with the violinist a couple times to work out the basic approach and then set about working up the harpsichord part. A month later I contacted the student because I hadn’t heard from her in a while and she replied nonchalantly oh gee, I decided not to do those, thanks for checking. I was appalled by the lack of consideration but when you’re dealing with students nothing should cause surprise. So I just said ok, thanks for letting me know and rang off. My approach to working with students changed at that point to ensembles only, because an ensemble is usually part of a program overseen by a faculty member. I was never again dumped summarily on the roadside. I only had one gig as continuo harpsichordist for an orchestral group. The experience was massively unsatisfying due to the dictatorial role of the conductor (a faculty member), which is Business As Usual for orchestral groups, really. I swore I’d never do it again — and I didn’t. Tell me not to use arpeggiated chords in a continuo part? Are you SERIOUS?? Forget that, bud. But putting aside such potholes in the amateur musical expressway things went fairly well and I’d say college groups offer one of the better ways amateurs can engage in playing the music they love.

There are colleges everywhere and if you’re an amateur who plays an unusual instrument — at the time I was on the scene Baroque flute and viola da gamba qualified as such — then occasionally you can be offered the opportunity to do some playing with college students. I always accepted such opportunities with an open mind and was always happy to share what I knew about Baroque performance practice. Was the music-making good? Sometimes yes, sometimes no. It’s a variable feast and requires low expectations with a lot of patience. I remember being brought onboard to do a couple of the Bach sonatas for violin and obbligato harpsichord (BWV 1014-1019), met with the violinist a couple times to work out the basic approach and then set about working up the harpsichord part. A month later I contacted the student because I hadn’t heard from her in a while and she replied nonchalantly oh gee, I decided not to do those, thanks for checking. I was appalled by the lack of consideration but when you’re dealing with students nothing should cause surprise. So I just said ok, thanks for letting me know and rang off. My approach to working with students changed at that point to ensembles only, because an ensemble is usually part of a program overseen by a faculty member. I was never again dumped summarily on the roadside. I only had one gig as continuo harpsichordist for an orchestral group. The experience was massively unsatisfying due to the dictatorial role of the conductor (a faculty member), which is Business As Usual for orchestral groups, really. I swore I’d never do it again — and I didn’t. Tell me not to use arpeggiated chords in a continuo part? Are you SERIOUS?? Forget that, bud. But putting aside such potholes in the amateur musical expressway things went fairly well and I’d say college groups offer one of the better ways amateurs can engage in playing the music they love.

The Frustrated Professional Group

This type of group can be extremely dicey. It can very good but it can also be a disaster. I’ve experienced both ends of the spectrum.

This type of group can be extremely dicey. It can very good but it can also be a disaster. I’ve experienced both ends of the spectrum.

By “frustrated professional” I mean someone who’s actually done the full roster of academic and performance studies, got the degree(s) and then for some reason (e.g. aversion to poverty LOL) did not take up music professionally. I wasn’t in that category because, as I said, I never completed the academic coursework to get the music degree, I just studied with private teachers to become a competent performer and carried on with my own musicological studies. These frustrated professionals for one reason or another ended up selling real estate or becoming bank loan officers or some such thing — after all, you gotta make a living, right? Whether playing with such people turned out to be good or disastrous depended entirely on how the people in question had come to terms with their life choice. It’s like wine — sometimes you get a great vintage, sometimes you get vinegar.

If people had come to comfortable terms with their decision they could be quite good fun and usually played very well because they’d studied seriously. If, however, the move away from a professional life in music was a derailment of some sort, then things could get gnarly very quickly. The gnarliness could manifest in all sorts of ways. Some of these types would take on themselves the role of ensemble director quite without any request from the group to assume that responsibility — after all they were professionals but just not working as such. The rest of us, of course, were lowly amateurs by comparison. Another variation on the theme I observed was a frantic attempt by one thwarted musicologist to stage an evening of German music from the early Baroque — concerted motets, in which I was one of the gambists — with people who had no idea what they were doing and would have been hard pressed to pull off a program of folksongs sung in tune. The results were disastrous and I swore then and there I would ply those troubled waters no more.

Retired people in the professional cateory aren’t frustrated and they’re the best bet, to be honest. I played with one retired clarinet professor whose retirement exiled him to Amateur Land like the rest of us Lumpengesindel. He played recorder for the Baroque music group I was in and he was fantastic. It was a joy to work with him and we did a couple public concerts that garnered great appreciation from the audience. That’s the best possible outcome from this particular scenario. I wish it had been more frequent in my experience.

Slumdogging With the Pros

In a couple instances after I left big cities behind me I ended up in smaller cities with a few music professionals interested in early music. Word somehow got out — as it does in smaller places — that I was trained as a harpsichordist and also played both Baroque flute and viola da gamba and had my own instruments. It’s unusual to find a Baroque flautist or a gambist in most smaller cities in the USA, so in a couple places where I lived I was actually recruited by local professionals (academics, of course) to participate not only in performance but also in teaching. The teaching was informal, to be sure, on the order of structured show and tell. I’d bring in my viola da gamba and show it to the class, give a little spiel and then play a piece or two. Most students had never seen the instrument in the flesh before and for some it was a point of interest, but early music was not a big deal for the majority.

In a couple instances after I left big cities behind me I ended up in smaller cities with a few music professionals interested in early music. Word somehow got out — as it does in smaller places — that I was trained as a harpsichordist and also played both Baroque flute and viola da gamba and had my own instruments. It’s unusual to find a Baroque flautist or a gambist in most smaller cities in the USA, so in a couple places where I lived I was actually recruited by local professionals (academics, of course) to participate not only in performance but also in teaching. The teaching was informal, to be sure, on the order of structured show and tell. I’d bring in my viola da gamba and show it to the class, give a little spiel and then play a piece or two. Most students had never seen the instrument in the flesh before and for some it was a point of interest, but early music was not a big deal for the majority.

In one instance I was asked to participate in a faculty concert — my job was playing continuo viol since there wasn’t anybody else within a 150 mile radius capable of doing it. Continuo is usually not too difficult, you don’t have to be able to grab double and triple stops like you do in the French solo literature, so I brought it off with a fair degree of aplomb. One point for the home team.

What I discovered in the course of that activity, however, was that I’d made the best possible decision not to go into music professionally. The second you put yourself into that category all kinds of untoward social pressures begin to mix into the musical business at hand because you’re vested in a professional hierarchy and must maintain your position in it for the sake of your livelihood. Those pressures come out in all sorts of ways that an amateur like myself picks up on right away. I felt like an anthropologist doing field observations on a group from some lost quarter of Amazonia. I watched them do the professional minuet with each other and observed carefully in what ways their treatment of me differed. After we had played a bit and they saw that I was indeed well up to the job, things became very curious. I got the impression that it didn’t entirely suit some of them that I played as well as I did. Obviously I was threatening the professional/amateur boundary in some way I hadn’t really thought much about. As usual, I was just interested in doing the music.

The upshot was that they talked shop among themselves, in which I obviously couldn’t participate. Whoopee do. Once they’d got that out of their system we got down to playing the music and I stopped thinking about it, but it kept coming back to the point that eventually I got tired of it. And to be perfectly frank, their playing often wasn’t particularly inspired since they had standard conservatory training, not specialized training in Baroque performance practice. They lacked imagination and weren’t very proficient in ornamentation. It was fun doing the music, however, so whenever they called me up to do something I agreed, until I finally moved away from the town. I’ve remained glad to this day that I never went into music professionally. My relationship to music has been all the better for it, I’m quite convinced of that, because it’s been completely free from the social hoopla involved with being a professional.

Performing Solo

Since my primary instrument is harpsichord I’m fortunate to have the option of doing solo stuff if I want to. As I moved to smaller places that was often the only option available with regard to public performance. It’s been a long time since I was up in front of an audience plonking away, but I did it as a denizen of some smaller cities and towns I’ve lived in since I could advertise “Have Harpsichord, Will Travel.” Some people took me up on the offer but never for cash — it was all for art for art’s sake. 🙂

Since my primary instrument is harpsichord I’m fortunate to have the option of doing solo stuff if I want to. As I moved to smaller places that was often the only option available with regard to public performance. It’s been a long time since I was up in front of an audience plonking away, but I did it as a denizen of some smaller cities and towns I’ve lived in since I could advertise “Have Harpsichord, Will Travel.” Some people took me up on the offer but never for cash — it was all for art for art’s sake. 🙂

For one performance on a Sunday afternoon in a handsome Episcopalian church I did a program of English Renaissance music — works from The Fitzwilliam Virginal Book and My Ladye Nevell’s Booke. It went down a treat, although I’m sure for many of the audience it was the first time in their lives they’d heard that kind of music so they had no idea whether my playing was good or bad. Another program I had great fun putting together included French Baroque music with works for both harpsichord and Baroque flute. Since as a solo performer you’re free to come up with your own ideas, you can be as creative as you like. As long as somebody’s willing to listen, it’s all good. I enjoyed that freedom and the opportunity to trot out literature I loved that I knew would be unfamiliar to the audience. As long as you have your own instrument(s) and can tote them around, you’re limited only by the willingness of people to sit and listen while you do your thing. Just don’t be surprised after you give a few concerts if you get asked to play for weddings and funerals. It’s gonna happen, trust me on that one, Bridget. 🙂

What Does It All Mean?

Good question. I still ask myself that when I come across programs from concerts I’ve played. I was dead serious about music from a very early age and have remained that way over the course of my entire life. I’m sure it won’t stop until I achieve the grave. As I watch videos these days on YouTube of early music performances, I see what a delight it must be to have that activity as the cornerstone of one’s lifework. If the world were different, choosing a career as a young person would have been a no-brainer. Music has always been my chief passion and I would have engaged it as a profession without hesitation. There were good reasons I didn’t do things that way and I’m content in my golden years that I chose well from a practical standpoint. I kept up my involvement with music to the greatest degree I could, steered clear of things that didn’t serve my musical purposes and had some fun along the way.

While doing background research for this post I came across an article by Janet Horvath, an American cellist who was first cello of the Minnesota Orchestra for 32 years. I found one of her articles (available here) with the intriguing title “The Magic of Amateur Musicians.” How could I not click on that link? It’s so rare for us amateurs to get kudos from a pro that I couldn’t resist. From her experience of serving as a faculty member at an amateur musicians’ conference come these thoughts:

… Each year for the last sixty years, hundreds of avid chamber music aficionados from far and wide have gathered for intensive chamber music playing at the Chamber Music Conference and Composer’s Forum of the East in Bennington, Vermont. These are amateur musicians, many of whom are quite accomplished players, who ultimately chose other careers and whose great passion in life is to make music.

Not a moment is wasted. They eagerly race from building to building and room to room, instruments in hand, choosing from the vast library of chamber music on hand arranged alphabetically, in large Tupperware containers spread across a huge hallway organized by size and instrumentation of the group—virtually everything for two to 10 players. The musicians read music from morning until night with nary a breath taken …

I was totally unprepared for what I encountered. The Bennington attendees’ vast knowledge of the literature was humbling, as they had played through much of the music time after time, year after year. They could pontificate about the composers and argue the finer points of interpretation, having availed themselves of every opportunity to compare various recordings.

Some of the players were quite accomplished and some not. But even so, there was only one rule: once the piece was started no one stopped for any stragglers or errors— no apologies accepted or needed. I couldn’t help being caught up in their sweeping joy of music making and after a few days I too was able to let go of my inhibitions about playing “unprepared.” I bit my tongue if I missed a note, stifling the “sorry” I might have uttered out of force of habit. (We professionals are always sorry if we make even the tiniest of errors.) I was able to savor the wonderful music, the collegiality and the friendships that ensued. Sight-reading music, volumes of it, was fun, revelatory.

There we have the lowdown from a pro about just how fun we amateurs can be. I’m astonished to learn that we’re “magical,” but hey, I’ll take it. She reports on what in early music circles would likely be called a “conclave.” We early music types don’t have “conferences,” we have “workshops” or “conclaves.” They’re usually heady affairs that happen once a year, obviously only those people with enough moolah go and there are always a few pros invited to serve as faculty members in order to lend a didactic element to the proceedings. Finding an early music gathering in the States of the sort Horvath describes was no easy job for long years. These days there are more of them, which is good news. They’re not cheap, however. You can expect a week-long workshop to set you back around $2K. That’s one way to keep out some of the riff-raff, but unfortunately riff-raff doesn’t include soccer moms with their Moeck recorders LOL.

My timing was bad as an amateur in the area of early music, that’s the verdict at this stage of my life. Had I been born 30 years later I’d have had a much more ample range of options available. Because I chose to move away from big cities, my choices inevitably became even more limited, but I’m not sorry I made that change. I have delights of a different order to remember because of it — long walks in lovely countryside, for example. The trade off was worth it, no doubt on that account.

I seem to rail all too often against the categories people continually stuff life into to no good effect. Life could so easily be organized differently. Musical life could be organized so that both professionals and non-professionals have easy access to all the resources available. It wouldn’t be that difficult to have a cultural branch of the Parks Department, for example, that uses municipal funds to put on programs of music instruction and performance for students and amateurs with the equivalent of workshop faculty onboard to organize and teach. But that’s just crazy talk, I know. Me and my looney ideas …

Online availability of musical resources has been without doubt the biggest new boon to amateurs like me. The Petrucci Music Library (IMSLP, here), to give one example, is a fantastic resources I use all the time and actively support. With such resources now only a click away, someone like me who’s serious about music but stuck out in the boondocks is no longer cut off from getting hands on the good stuff. Two thumbs up for that change. It breaks down the domain boundaries between professional and non-professional in a way I find very encouraging. In my rural backwater I can pull up and read some dissertation from a central European university on some obscure Baroque composer as easily as anybody in academia can. In my young days you had to be in academia yourself to accomplish such a feat. That change deserves the name “progress” in the best sense of the word.

It’s been a good run in Amateur Land, I can’t complain too bitterly. For the remainder of my natural lifetime I’ll continue to tickle ivories, toot, and strum. Never say die, right? So onward we go and damn the torpedoes. See you at a workshop sometime. 🙂