April 2020

The Renaissance is a thing of many splendors. This post focuses on Renaissance composers whose works have come to mean something special to me over the course of my lifetime of involvement with music. When I think about the world of Renaissance music I see that my awareness of it in the early part of my life was skewed both by the limitations of the canon — no, Bridget, Palestrina wasn’t the only game in town — and the paucity of recordings of music across the full range of Renaissance repertoire. The canon has seen its boundaries broken down over the past few decades and the number of recordings has increased dramatically, circumstances that have brought to eye and ear a much fuller and truer picture of musical life in the period. My collection has had full benefit from that change and I own recordings that I’d definitely put into the bag I have at the ready if the house catches fire and I need to grab my valuables and run. This post is my shoutout for some of the Renaissance composers whose works have become important companions of my days. Some names may be familiar but some, I think, will not be, which is a pity. So here we go, let’s get started.

The Renaissance is a thing of many splendors. This post focuses on Renaissance composers whose works have come to mean something special to me over the course of my lifetime of involvement with music. When I think about the world of Renaissance music I see that my awareness of it in the early part of my life was skewed both by the limitations of the canon — no, Bridget, Palestrina wasn’t the only game in town — and the paucity of recordings of music across the full range of Renaissance repertoire. The canon has seen its boundaries broken down over the past few decades and the number of recordings has increased dramatically, circumstances that have brought to eye and ear a much fuller and truer picture of musical life in the period. My collection has had full benefit from that change and I own recordings that I’d definitely put into the bag I have at the ready if the house catches fire and I need to grab my valuables and run. This post is my shoutout for some of the Renaissance composers whose works have become important companions of my days. Some names may be familiar but some, I think, will not be, which is a pity. So here we go, let’s get started.

![]()

Anonymous

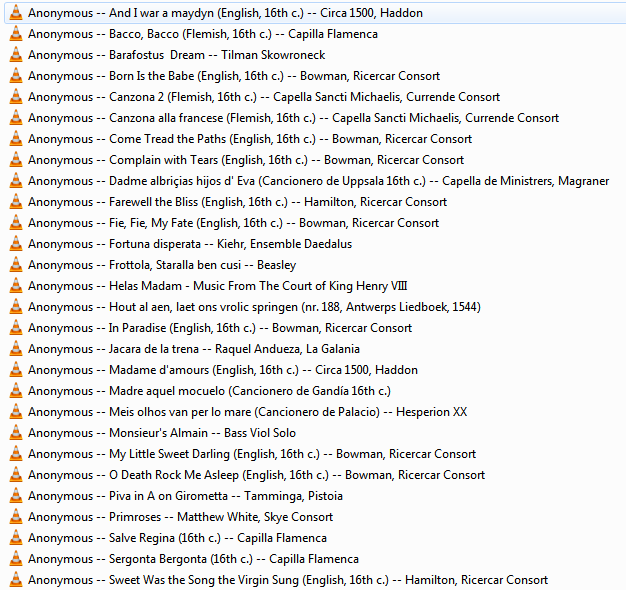

The first thing that sprang to my attention when I went over my list of recordings from the Renaissance is how much Anonymous is represented. The cultural change that led to the disappearance of Anonymous in the Baroque period is worthy of a dissertation by some doctoral student of music history, don’t you think? I’m reminded of what Virginia Woolf said in A Room of One’s Own about “Anon” in regard to literature:

… Indeed, I would venture to guess that Anon, who wrote so many poems without signing them, was often a woman. It was a woman Edward Fitzgerald, I think, suggested who made the ballads and the folk-songs, crooning them to her children, beguiling her spinning with them, or the length of the winter’s night.

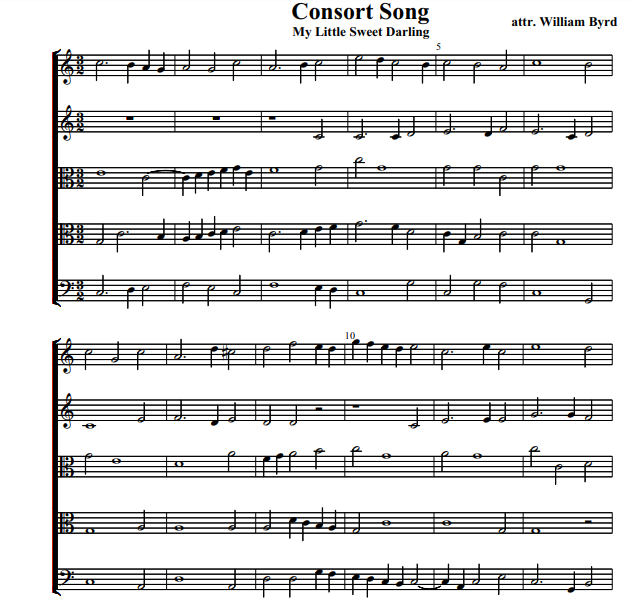

It wouldn’t surprise me to learn that musical compositions from “Anonymous” also include works by women. But whatever the case may be, Anonymous has some very fine works to his or her credit. One of my favorites for the past twenty-odd years is the consort song “My Little Sweet Darling.” It has been attributed to William Byrd but that attribution has no legs to stand on. I’m sticking with Anonymous as the composer. It’s a composition more than worthy of Byrd, who as we all know was a magnificent composer, but isn’t it fun to think about the composer being someone whose first name is Margaret or Joan instead of William? Since it’s a Supermom song I like to think it could well have been written by a woman.

Our obsession with attribution is a thing of relatively recent date, as Bruce Haynes, the well known Baroque oboist, explains in his book The End of Early Music: a Period Performer’s History of Music for the Twenty-First Century:

The true Canonic musical experience requires knowing who wrote the piece one is hearing, knowing when they lived, and knowing where they fit in the hierarchy of the Pantheon. For his dissertation, John Spitzer traced the histories of works attributed to great composers that were later proved spurious; they disappeared from the repertoire when they lost their pedigrees. Spitzer observed how, when in 1964 they were re-ascribed to Hofstetter, Haydn’s Opus 3 string quartets began to disappear from the repertoire. The same phenomenon occurs in painting and literature.

The label, it seems, is more important than the product. This is disgraceful, but I have to say that for myself, and I believe most musicians, a true appreciation of a piece is not possible until its composer is known. Spitzer writes of how this influences our perception of the work’s identity and qualities. As he says, “changing the name amounts to altering the work itself.” Think of the discomfort we feel when turning on the radio in the middle of a piece and impatiently waiting for the end, to identify the composer and performers! … As Spitzer observes, knowing its authorship satisfies our need to put art into its historical context (since it is no longer in one). It also contributes to our sense of a piece’s identity, since each performance is a little different (and in some cases so different as to render the music unrecognizable).

Musicology was invented in the Romantic period, and its first activity was the production of countless biographies and collected-works of numerous artist-composers. This was natural, since the dominant paradigm in Romantic music was the hero/composer and the “masterpiece.” But it gave the Romantics an unholy obsession with attributing works, and who influenced whom.

There’s relatively little of Anon in the Baroque period — the development of the new style was centered on places of renown with people who were about the business of making a name for themselves. Music publication had also entered a more robust stage of development and nobody put “Anonymous” on their collection of sonatas or madrigals, the name is front and center and followed by a dedication that gives all manner of information about how the music came to be and its relevance to the Great Person to whom it’s dedicated. The Renaissance by contrast has lots by Anon, as you can see from a partial listing of tracks in my collection:

As for particulars, let’s take that consort song I mentioned, “My Little Sweet Darling,” as an example. In the score available on the IMSLP site one finds an attribution to William Byrd. The webpage for the score announces that the attribution is uncertain. Indeed it is, uncertain enough to be wholly absent from mention in Musica Britannica. Here’s the first bit of it, which shows the sophistication of the writing:

The track in my collection has Bowman singing the vocal line (the second staff in the score) with the Ricercar Consort providing the accompanying viol consort. I know this piece as a performer, as well, because I’ve played it in performance, treble viol on the top line. It’s an enormously lovely piece of music, the part writing so beautifully woven together and the melody so sweet it pulls your heartstrings. I knew it only as by Anon until I came across the IMSLP score with the tentative attribution to Byrd. As I said, the music is certainly worthy of Byrd’s name, magnificent composer that he was, but it’s beautiful no matter who wrote it and I don’t feel the need to know the composer’s name, particularly if it involves a spurious attribution. Anonymous is just fine with me. You can hear Bowman’s performance on YouTube here. There’s a performance by Hesperion XX with soprano Monserrat Figueras also on YouTube, with exceptionally lovely viol parts (as one would expect from Jordi Savall), available here.

So let’s have a shoutout for Anonymous, who wrote some wonderful stuff and deserves a warm round of applause. My experience of Renaissance music would be much the poorer without Anon’s contributions, so let’s give credit where credit is due for some great music. As Shakespeare said, a rose by any other name etc. etc. Right?

![]()

John Coprario (English, 1570?-1626)

Let’s get the bio up first since Mr. Coprario is hardly a household name. There’s a good one on the HOASM website (here):

English composer. Born John Cooper but had begun to use the Italianate surname by 1601. Cooper served at the English court from 1605 to 1626 as lutenist, gamba player and composer, and taught the future King Charles I and also Henry and William Lawes. In the service of Queen Anne from 1605, by 1608 he was also in the private service of Sir Robert Cecil, 1st Earl of Salisbury. Through 1612 he taught Prince Henry (d. 1613). In 1616-17 he traveled in Europe. In service of Prince Charles (Charles I) 1618-25. Composer in Ordinary through his death in 1626.

There is no concrete evidence that he before 1604 visited Italy and adopted the name Giovanni Coperario, which he kept after returning home; the story nonetheless persists. Almost all of his works are secular, but he was in distinguished company in appearing in Leighton’s 1613 The Teares or Lamentacions of a Sorrowfull Soule. He published two books of lute songs (Funeral Teares and Songs of Mourning) and was a prolific composer of fantasias, some ninety in from three to six parts being extant, suites for consort, some Italian villanellas, and a treatise Rules how to compose, written before 1617, a practical manual with original musical examples. His fantasias for viols show the progress of idiomatic instrumental writing, but more important are his four consort suites, both for their novel medium of one or two violins with bass viol and organ (although the music for the organ is merely a reduction of that allotted to the other three instruments), and for their development of the concept of the suite: each consists of a Fancy, an Almane, and a Galliard.

His ‘A maske’, set by Giles Farnaby, is to be found in the Fitzwilliam Virginal Book.

Useful Link: Richard Charteris [Author “John Coprario (Cooper), c. 1575-1626: A Study and Complete Critical Edition of His Instrumental Music” (diss., Univ. of Canterbury, New Zealand, 1976). Id., A Thematic Catalogue of the Music of John Coprario with a Biographical Introduction (New York, 1977)]

Quite the spate of name-dropping: Charles I, Queen Anne, Sir Robert Cecil, ooh la la. Fortunately Coprario died before things went off the rails with Charles I and ended up in that spot of bother outside the Banqueting House in 1649 (we can appropriately pinch a phrase from the Red Queen: off with his head!). It’s also worth mentioning that his pupil William Lawes became one of the finest composers of instrumental music in the following generation. He didn’t share his teacher’s good luck with regard to avoiding spots of bother, however. He got thrown into the thick of the Civil War and as his Wikipedia page reveals, “he was ‘casually shot’ by a Parliamentarian in the rout of the Royalists at Rowton Heath, near Chester, on 24 September 1645.” As I always say, it never pays to mix business and politics …

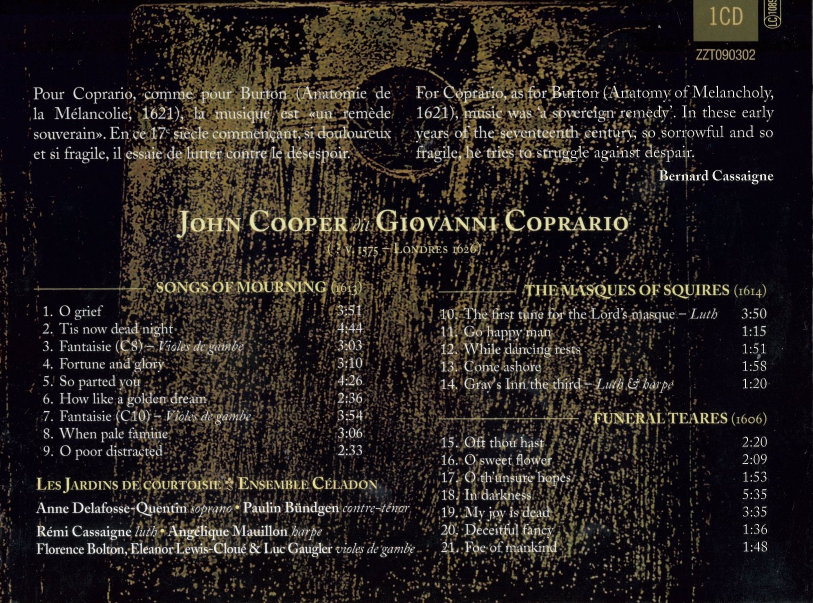

I only own one recording of music by Coprario but it’s one I’d definitely have in my ready bag to grab if the house catches on fire. Bearing the title Funeral Teares it contains pieces from that collection of songs published in 1606 together with music from The Masques of Squires (1614) and Songs of Mourning (1613). The songs are exquisite pieces of vocal writing. The vocalists on the recording are excellent — countertenor Paulin Bündgen (French, despite the Teutonic-looking last name) and soprano Anne Delafosse-Quentin. They are avid practitioners of historic performance practice including the use of English pronunciation ostensibly of the period, which works some obfuscation on one’s attempt to understand the texts when sung. Here are recto and verso of the cover:

The first time I heard one of the pieces — it was “How Like a Golden Dream” from Songs of Mourning (in the performance the word “how” sounds like the name Hugh) — I was gobsmacked. I knew right then and there I had found another companion of days and so it has been these past several years. You know a peak experience when you have one, it’s not rocket science.

The songs of Funeral Teares are for two voices and those of Songs of Mourning are for solo voice. It’s a testament to Coprario’s finesse as a musician and composer that the differences between the solo and two-part songs are very telling. The writing for solo voice is arresting because of its balance between the melodic and the declamatory. In other words, the music fits the natural rhythm of the text to perfection. In the hands of inventive and sensitive performers like Ensemble Celadon and Les Jardins de Courtoisie the results are revelatory. It’s like you can hear the song take breaths between speaking the lines, just as a person would do. Fantastic.

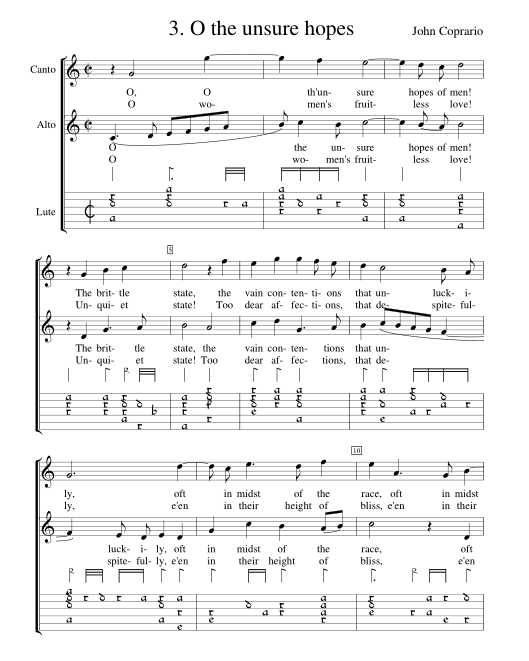

The two-part songs are wonders of melodic and rhythmic invention. One of the techniques Coprario uses to particularly good effect is an octave jump that brings the lower voice (sung by Bündgen) abruptly and surprisingly into close harmony with the upper voice, usually at a cadence point. I find the effect haunting and lovely, like the hoot of an owl coming from the forest in the nighttime. I should add that Coprario wrote the works as lute songs but the performance on the recording adds harp and viols to the mix to wonderful effect. Let’s have a look at one of my favorite pieces, “O th’unsure hopes of men” from Funeral Teares:

The first thing that jumps to my attention is the difference in tessitura. The soprano voice stays fairly high and the alto (countertenor, in the case of the recording) moves about athletically from low to high tessitura. From a rhythmic standpoint the two voices are offset save at the cadence points, which makes each phrase between cadences tense because there’s a lot to listen to in both voices. I had to reschool myself as I listened repeatedly to this song, focusing first on the soprano and then on the alto before listening to them in combination. The writing is all about playing the voices off each other to create texture and the focus on the declamatory one finds in Songs of Mourning goes completely missing. The text is wrenched into position to fit the rhythmic interplay, with some words given such short shrift that it becomes difficult to understand them when sung. But it’s all good IMHO since the music is what matters. I never tire of following the interplay of the two voices. The rhythmic complexity of the interrelation between the two continually fascinates me.

Unsurprisingly there’s not a lot of Coprario recordings on the market. The recording by Ensemble Celadon is still available on Amazon. What’s available of Coprario’s music on YouTube is poor pickings, if you ask me — certainly nothing up to the high standard set by the recording done by Bündgen and Delafosse-Quentin. Jordi Savall has done a recording of Coprario’s consort music, which is superb as is usually the case with his recordings, but it’s not the songs. So there’s only one go-to for the songs and that’s the recording I’ve discussed here. This is a case for pounding on the drum of quality over quantity if ever there was one. Have a listen and I think you’ll find that you, too, have had a peak experience.

![]()

Michael East (English, ca. 1580-1648)

Since East is definitely not a household name here’s some biographical info from his Wikipedia page (here):

In 1601, East wrote a madrigal that was accepted by Thomas Morley for publication in his collection The Triumphs of Oriana. In 1606, he received a Bachelor of Music degree from the University of Cambridge and in 1609 he joined the choir of Ely Cathedral, initially as a lay clerk. By 1618 he was employed by Lichfield Cathedral, where he worked as a choirmaster, probably until 1644, when the Civil War brought an end to sung services. Elias Ashmole was a chorister at Lichfield, and later recalled that “Mr Michael East … was my tutor for song and Mr Henry Hinde, organist of the Cathedral … taught me on the virginals and organ”.

East’s exact date of death is not known, but he died at Lichfield. His will was written on 7 January 1648 and proved on 9 May 1648. It mentions his wife Dorothy, daughter Mary Hamersly, and a son and grandson both named Michael.

The madrigal of East’s included in Morley’s compilation The Triumphs of Oriana, obviously for Queen Elizabeth, is “Hence Stars! Too Dim of Light.” You can hear it on YouTube here in a performance by The Sarum Consort.

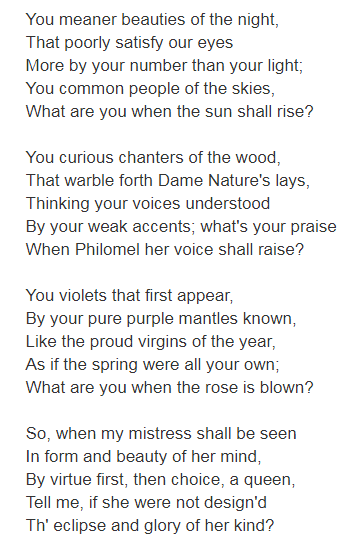

I became acquainted with Michael East through his music for viols when I was involved in consort playing. His duos for two bass viols are fantastic and great fun to play. It was only years later that I came across one of his songs, “You Meaner Beauties of the Night,” in a performance by the inimitable Emma Kirkby, who has, I think, reached Guinness-book status for the number of things she’s recorded over the years of her career. I recently came across a more recent performance on YouTube (here) by the ensemble I Ciarlatani with soprano Kerstin Bruns taking the lead. Her voice is lovely and the viol consort accompanying her does an even better job than Anthony Rooley’s group in Kirkby’s performance. The poem is a concoction of Sir Henry Wotton, who was quite a character (info here) and counted among his friends both John Donne and Izaak Walton (of The Compleat Angler fame). I never paid much attention to the text until I researched it for this post and read the poem carefully. I’m embarrassed by my reaction to the words, so vastly different from my response to East’s music. It strikes me as yet another of those Elizabethan ditties that read on close inspection like dodgy pick-up lines in a bar — an extremely elevated version of “hey gorgeous, where have you been all my life?” Here’s the text:

If we confine our imaginations to nymphs and shepherds and such things it’s fine, less so if we picture to ourselves bawdy lads and wenches down the pub carrying on as I’m sure Elizabethans were wont to do.

As for East’s consort song there’s no question that it’s top-drawer and as lovely as can be. I can’t find the score for it, sorry to report, or I’d show you the goods. Suffice it to say that it’s structurally sophisticated with a viol consort introduction, a section for solo soprano voice with a lovely, soaring line and a three-part setting (SAT from what I can tell) of the last line of each strophe. Let’s keep our fingers crossed that East is one of the fine composers who gets caught up in the same trend that brought us the recording of Coprario’s music.

![]()

Gaspar Fernandes (Portuguese, 1566-1629)

If Fernandes were alive today I’m convinced he’d be one of the top EDM DJs on the Ibiza circuit and fabulously wealthy as a result. He’s a hard act to follow when it comes to sheer inventiveness and creativity. His music fairly erupts off the page. The first time I heard it on a recording by the instrumental group Piffaro I could hardly believe my ears. And his life is as surprising as his music as his Wikipedia page (here) reveals:

Gaspar Fernandes (sometimes written Gaspar Fernández, the Spanish version of his name) (1566–1629) was a Portuguese-Mexican composer and organist active in the cathedrals of Santiago de Guatemala (present-day Antigua Guatemala) and Puebla de los Ángeles, New Spain (present-day Mexico).

Most scholars agree that the Gaspar Fernandes listed as a singer in the cathedral of Évora, Portugal, is the same person as the Gaspar Fernández who was hired on 16 July 1599 as organist and organ tuner of the cathedral of Santiago de Guatemala. In 1606, Fernandes was approached by the dignitaries of the cathedral of Puebla, inviting him to become the successor of his recently deceased friend Pedro Bermúdez as chapel master. He left Santiago de Guatemala on 12 July 1606, and began his tenure in Puebla on 15 September. He remained there until his death in 1629. …

During his Puebla tenure, rather than focusing on the composition of Latin liturgical music, he contributed a sizable amount of vernacular villancicos for matins. This part of his output shows great variety in the handling of texts, which are in Spanish but also in pseudo-African and Amerindian dialects and occasionally Portuguese. One of these villancicos, “Xicochi,” is notable for its use of Nahuatl, the language of the indigenous Nahua people. The music departs from 16th century counterpoint and reflects the new baroque search for textual expression. The main collection of these villancicos is extant in the Oaxaca Codex, and has been studied, edited, and published by Robert Stevenson and especially by Aurelio Tello.

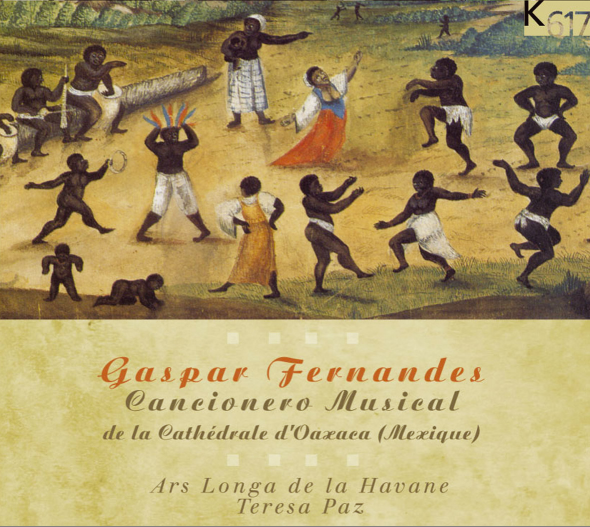

It’s a recording of villancicos that I have in my collection, from the Cancionero Musical de Oaxaca edited in modern edition by Aurelio Tello as mentioned in the citation. The performance is by Ars Longa, a group from Havana, Cuba directed by Teresa Paz. Here’s the cover:

The Cancionero is one of the most important collections of music from New Spain, as this info from the website musicaantigua.com (here) describes:

Un cantor, Gabriel Ruiz de Morga, llevó consigo a Oaxaca, hacia 1653, un cuaderno que contiene 300 composiciones polifónicas escritas a mano (el Cancionero Musical de Gaspar Fernandes), la mayor parte de ellas firmadas por Gaspar Fernandes.

No sé sabe uso tuvo este cuaderno en los años y siglos siguientes, pero resistió los embates del tiempo, los saqueos, los descuidos humanos y llegó, más o menos completo, al siglo XX.

En el Archivo Musical de la Catedral de Oaxaca se encontró la colección íntegra del Cancionero Musical de Gaspar Fernandes con más de 300 canticos religiosos populares, en su mayoría escritos en español y Náhuatl.

La gran incidencia de villancicos con la indicación de portugués podría confirmar el origen de Gaspar Fernández, especialmente por el correcto empleo del idioma.

También indica Fernández composiciones en biscayno, en negro o en indio, según en lo que estén escritos los textos.

Muchos están designados como negro, negrito, guineo o negrilla, y son muestra de la importancia que tuvo la cultura africana en América a principios del s. XVII.

[A singer, Gabriel Ruiz de Morga, took with him in 1653 to Oaxaca a notebook containing 300 polyphonic compositions in manuscript … the majority of which are signed by Gaspar Fernandes. We don’t know what happened in the following years and centuries, but the notebook managed to escape the ravages of time, conflict and human neglect to arrive at the 20th century more or less complete. In the Musical Archives of Oaxaca Cathedral the collection was found with its more than 300 religious popular songs, written for the greater part in Spanish and Nahuatl. The predominance of villancicos with the indication “Portuguese” confirms their origin from the pen of Gaspar Fernandez, especially since the language is used correctly. Fernandez also indicates composition in Basque and “negro” o “Indian” according to the language of the text. Many texts are indicated as “negro, negrito, guineo or negrilla,” a testament to the importance of African culture in America at the beginning of the 17th century.]

I checked Amazon to see if the Ars Longa recording is available and the answer is no, unfortunately. To steer you to some music by Fernandes I have recourse yet again to YouTube, where there are some very good tracks, especially those from the recording entitle Folias Criollas by Hesperion XX with Jordi Savall. If you poke around you’ll find others, including some a cappella ones that show the rhythmic explosiveness of Fernandes’ music especially well. He was a Renaissance rocker, there’s no two ways about it. Have a listen and see if you don’t find your toes tapping — I bet you will. 🙂

![]()

Tobias Hume (English, c. 1569-1645)

To anyone who has by predilection delved into the literature for viola da gamba, Hume will be a known quantity. His works for the instrument count among the most important in the literature from any period, not only from the Renaissance period. But if you’re not an aficionado of viol music Hume may well be an unfamiliar name. The most important thing is to become familiar with his music, which is superb. As for his biography, it’s a dodgy business and may well leave your eyebrows higher at the end than they were at the beginning. The best bio on Hume I’ve found is on the HOASM website (here) which does us the favor of reproducing Hume’s preface to the reader from his collection Musicall Humours of 1605, to wit:

I Doe not studie Eloquence, or profess Musicke, although I doe love Sence, and affect Harmony: my Profession being, as my Education hath beene, Armes, the onely effeminate part of me, hath beene Musicke; which in mee hath beene alwayes Generous, because never Mercenarie. To prayse Musicke, were to say, the Sunne is bright. To extoll my selfe, would name my labors vaine glorious. Onely this, my studies are far from servile imitations, I robbe no others inventions, I take no Italian Note to an English dittie, or filch fragments of Songs to stuffe out my volumes. There are mine own Phansies expressed by my proper Genius, which if thou dost dislike, let me see thine, Carpere vel noli nostra, vel ede tua, Now to use a modest shortnes, and a briefe expression of my selffe to all noble spirites, thus, My title expresseth my Bookes Contents, which (if my Hopes faile me not) shall not deceive their expectation, in whose approvement the crowne of my labors resteth. And from henceforth, the stateful instrument Gambo Violl shall with ease yeelde full various and as devicefull Musicke as the Lute. For here I protest the Trinitie of Musicke, parts, Passion and Division, to be as gracefully united in the Gambo Violl, as in the most received Instrument that is, which here with a Souldiers Resolution, I give up to the acceptance of at noble dispositions.

He was a military mercenary for the greater part of his life and fell on hard times in his later years, being admitted in 1629 to the London Charterhouse (a kind of military old-folks home) where he died in 1645. Before achieving his end he apparently went a bit dotty, as described in his Wikipedia page (here):

His mind seems to have given way, for in July 1642 he published a rambling True Petition of Colonel Hume to Parliament offering either to defeat the rebels in Ireland with a hundred ‘instruments of war,’ or, if furnished with a complete navy, to bring the king within three months twenty millions of money. He styles himself ‘colonel,’ but the rank was probably of his own invention, for in the entry of his death, which took place at Charterhouse on Wednesday, 16 April 1645, he is still called Captain Hume.

Goodness sakes. Never a dull moment. It’s all a crashing pity because his music should have secured him a position among the musical establishment of the day on the basis of its merits, but musical merit was less important than position in the cultural hierarchy and connection to the aristocratic ranks who supported musical life as part of their dominance over the political and economic life of the country. So there was no place for an ex-military mercenary who happened to write excellent music for the viol. The early music revival has rehabilitated Hume and given him his rightful place in the musical scheme of things. I hope Hume looks down from on high (assuming that’s where he ended up) with a sense of vindication. He deserved better during his lifetime.

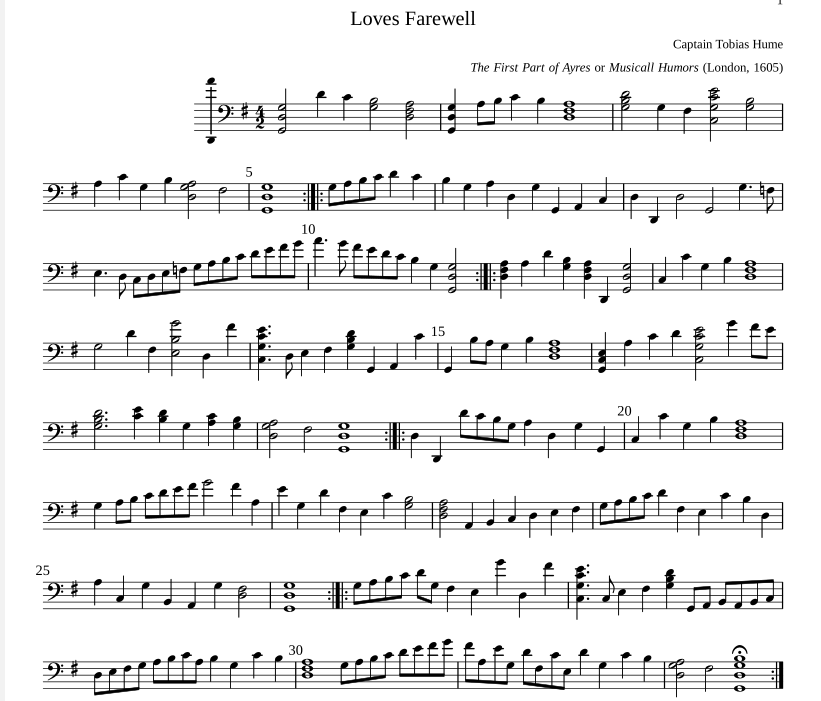

Hume wrote two collections during his lifetime, the Musicall Humours of 1605 mentioned above and Captaine Humes Poeticall Musicke published in 1607. The first collection is for solo viol, the second primarily for two bass viols but in essence it’s ensemble music, including songs such as the famous “Tobacco.” The solo works combine a focus on melody with the use of harmonic elements (achieved by the use of double stops and arpeggiation) to create a music I would describe as “wistful.” Lovely, but haunting in a way with a faint edge of melancholy. Maybe it’s just me … A favorite piece of mine entitled “Loves Farewell” serves as a good example of being cheery and wistful at the same time:

I own four recordings of works by Hume. One is exclusively of solo works from Musicall Humours performed by the inimitable Jordi Savall. As you’d expect from Mr. Gamba the playing is superb, I suspect in part because of a certain affinity of temperament between Savall and the composer. Somehow I can easily imagine them together down the pub locked in deep discussion of matters musical. I wager they’d seem two peas in a pod in that regard, although Savall would probably draw the line at proposing wacky military schemes to national legislative bodies. The recording is still available on Amazon and you can hear several tracks from it on YouTube, lucky you.

The other three recordings are either entirely from the second collection, Captaine Hume’s Poeticall Musicke, or a mix of works from both collections. Among my favorite performers on the viol is the duo Les Voix Humaines consisting of gambists Susie Napper and Margaret Little. Their major claim to fame is a recording of the complete works for two bass viols by the Sieur de Ste Colombe, which I own and heartily recommend. They have recorded the Poeticall Musicke in the spirit Hume intended, sticking primarily to two bass viols supported by a lute on occasion, but not much more. Hesperion XX has done a recording of the Poeticall Musicke using a full ensemble — winds, strings, the works — which brings a very different and sonically sumptuous version of the collection to ear. I consider them so different from each other they both seem worth having, each on its own merits. I also have a recording of works from both collections directed by Nima ben David, the Israeli gambist who has become a fixture on the early music scene. The (very good) countertenor Damien Guillon and tenor Bruno Boterf do the singing when it comes time to render the songs from Poeticall Musicke. Sonically speaking I find ben David’s rendering of solo works from Musicall Humours the best because it gives the instrument space to speak into a reverberative room. Savall’s recording of the solo works is at much closer range, so that you can almost hear the bow scrape against the strings. The viol’s sonority benefits from a bit of reverb, in my opinion (speaking as a player, not only as a listener), so I welcomed the ben David recording with that envelope of reverberation adding depth and resonance to the sound.

I’ve checked Amazon and all these recordings are still available there, mirabile dictu. YouTube also has plenty of Hume’s music on offer, including a full version of Savall’s recording of Musicall Humours, ooh la la. I feel I have the best of the lot in my collection already so I’ve not been tempted to add more, although I could be persuaded should I come across one that appeals either by reason of performer or performance approach. So go nuts and listen to them all, you’ll find yourself a friend of Hume in short order, I warrant.

![]()

Gerhardus Scronx (Belgian, fl. early 17th century)

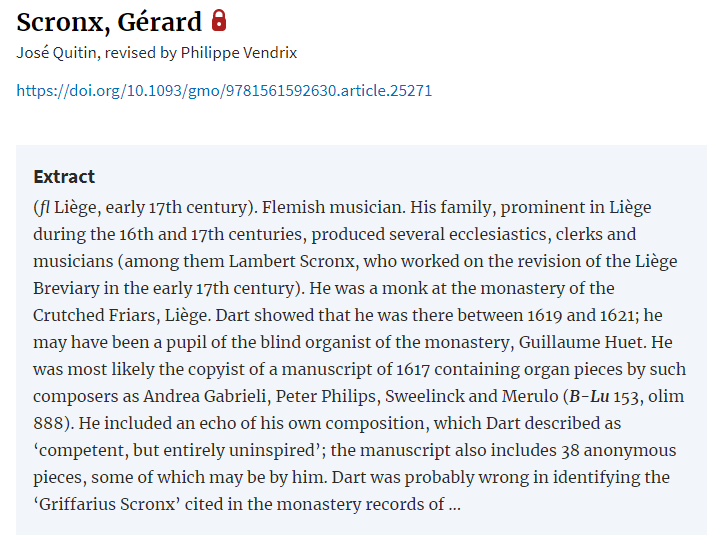

Scronx remains almost without biographical detail. I’ve only found one thing worthy of transmission, to wit:

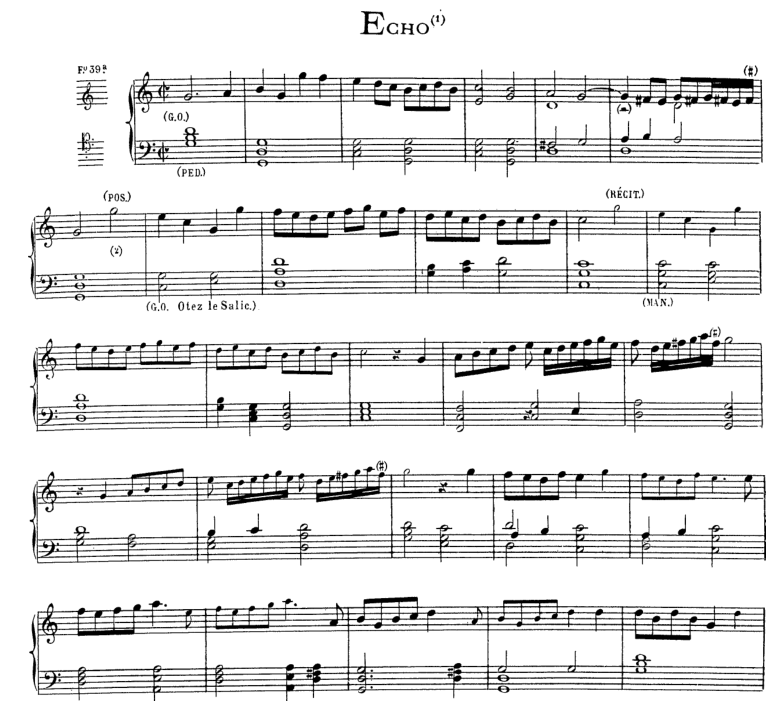

It’s an excerpt from the entry for Scronx from the online Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Only two works by Scronx are in the repertoire, both echo fantasies in the Netherlandish style, one in F major and the other in G major. Despite Thurston Dart’s dismissive assessment thereof as “competent but entirely uninspired” they continue to be recorded by organists of all ilks, which disproves the dishing they get from Dart, wouldn’t you say? I find both the works entirely lovely and listen to them regularly, especially the one in G major in a performance by Liuwe Tamminga on a wonderful organ by Willem Hermans in Pistoia, Italy, which you can access on YouTube here. I have the score of the G major piece, here’s a bit of it so you can see what’s up:

The fact that both works by Scronx were edited by Alexandre Guilmant for inclusion in his series Archives des Maîtres de l’orgue also gives the finger to Dart’s snarky comment. While it’s true we’re not talking about a double fugue by Max Reger, isn’t there room in the world for some simple, tuneful and heartwarming music for the organ? Isn’t that perhaps why the works by Scronx have been recorded so many times by so many different organists? There’s obviously some reason Scronx keeps turning up on recordings and concert programs. So let’s give credit where credit is due and do a shoutout for the obscure Scronx, whose pieces are a delight. Besides, it’s fun just to say his name while trying to keep a straight face. 🙂

![]()

Thus ends our list of shoutout composers from the Renaissance. Bless their hearts, every one. There are many others worthy of being shouted out ( or outshouted?) but I’ll leave the list as it is in order to comply with the requirements of propriety regarding the length of blog posts. If I were to compare the time I spend with various period of music to rooms in a house, I’d have to admit that the Renaissance is not the room with the TV in it. That’s definitely the Baroque. But the Renaissance Room is comfortable, rather like a study with nice pictures on the wall and an espresso machine in the corner with the wet bar. I have much more to discover in it, so when things build up expect another list of shoutouts for fantastic composers from the Renaissance, since it only makes sense to sing the praises of excellent composers. And I’m 100% on Hume’s page, since “I Doe not studie Eloquence, or profess Musicke, although I doe love Sence.” Amen to that.