September 2019

A look at the listings under the menu rubric Culture and Arts might lead you to think I’m obsessed with music of the Baroque period. BINGO! I’ve been a devotee since my teens and the force of the attraction hasn’t abated in the slightest over the course of my lifetime. If, on the other hand, you held me at gunpoint and commanded me to name five operas by Verdi, I’d likely not live to tell the tale. This intense interest in the Baroque has led me over the course of my adult lifetime to explore as many of its nooks and crannies as possible.

A look at the listings under the menu rubric Culture and Arts might lead you to think I’m obsessed with music of the Baroque period. BINGO! I’ve been a devotee since my teens and the force of the attraction hasn’t abated in the slightest over the course of my lifetime. If, on the other hand, you held me at gunpoint and commanded me to name five operas by Verdi, I’d likely not live to tell the tale. This intense interest in the Baroque has led me over the course of my adult lifetime to explore as many of its nooks and crannies as possible.

The purpose of this post is to highlight some unsung superstars of the Early Baroque, a portion of the Baroque period that has my special affection. As a performer I’ve worked mostly in the High Baroque period because that’s where the meat and potatoes is for the instruments I play (Baroque flute and harpsichord). I’ve certainly delved into the repertoire of the Early Baroque as a performer, as well — with regard to the keyboard literature, at any rate — but it’s as a listener that I’m most au courant with the magnificent music the Early Baroque has to offer. So this post is my shout out to those composers who deserve more attention. The music they composed is so lovely it deserves every ear that turns its way.

The big names of the period are easy to rattle off: the Gabrielis, Girolamo Frescobaldi, Claudio Monteverdi (definitely superstar status there), Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber (who has made quite a splash in recordings over the last twenty years), Francesco Cavalli (Mr. OperasRUs), Heinrich Schütz, Louis Couperin (a Big Deal if you’re into keyboard music) — I needn’t multiply examples. They stand out in the canon because of their importance in music history rather than just because they wrote great stuff. Monteverdi was the great champion of the seconda pratica (info here), which turned Renaissance music-making on its ear with an emphasis on tone painting and expressivity. A respected composer from the mid-16th century would likely think Monteverdi had gone off his meds. I’m as much a fan of the Renaissance way of doing things as the next guy — I’m a great admirer of prima pratica (info here) with its counterpoint as solid as houses, its strict rules for voice leading and all the rest of it. But the new way, especially Monteverdi’s stile concitato (= “agitated style” — info here) has so much excitement and interest it’s irresistible. I still go back to the greats of the Renaissance tradition like Palestrina and Orlando de Lasso, but my heart inclines natively to the Baroque — equally to the Early Baroque as to the High Baroque I know so well as a performer. There are such wonders to be found among the composers of the 17th century that to have lived without their music in my life would have made it much the poorer. I feel lucky that Early Baroque music got caught up in the Baroque revival of the 20th century and yielded so many fine recordings.

The composers I’ve chosen to highlight in this post deserve to have superstar status in my opinion, but for one reason or another they remain on the sidelines of musical awareness save for a small coterie of devotees. I’ve chosen ten composers to bring to attention in the hope that they’ll enrich your own musical experience as they’ve done mine. I harbor special fondness for each of them because of the many years of musical companionship they’ve brought me. When you find something wonderful you want to share it — so let me get busy and do just that. This time I’m getting serious and following alphabetical order, woohoo. I don’t want anybody calling me a slouch when it comes to getting my musicological ducks in a row. We have standards to maintain, after all, don’t we. Of course we do. 🙂

![]()

Johann Rudolph Ahle (German, 1625-1673)

The German Wikipedia page on Ahle (here) has much better biographical information than the English one, so let me use the former rather than the latter and do a spot of translation:

Ahle stammte aus einer Kaufmannsfamilie. Seine Schulzeit absolvierte er in Mühlhausen und Göttingen und studierte schließlich an der Philosophischen Fakultät in Erfurt. Dort amtierte er ab 1646 als Kantor an der Andreaskirche. Nach seiner Rückkehr nach Mühlhausen im Jahre 1649 arbeitete er zunächst als freier Musiker, bis er 1654 zum Organisten an der Hauptkirche Divi Blasii bestellt wurde. Er bekleidete ab 1655 als Mitglied des Stadtrates zahlreiche städtische Ämter und wurde in seinem Todesjahr zum Bürgermeister der Freien Reichsstadt gewählt. Nach seiner Rückkehr nach Mühlhausen 1649 heiratete Ahle im Jahre 1650 Anna Maria Wölfer. Ihr 1650 geborener Sohn Johann Georg Ahle machte sich ebenfalls als Komponist und Organist einen Namen und war wie sein Vater auch dichterisch tätig. Er trat nach seinem Tod dessen Nachfolge als Organist an der Kirche Divi Blasii an.

[Ahle came from a merchant family. His school years were spent in Mühlhausen and Göttingen and he studied philosophy at Erfurt. In 1646 he took a position there as Kantor of the Andreaskirche. After his return to Mühlhausen in 1649 he worked first as a freelance musician, then in 1655 took the position of organist at the main church, St. Blasius. From 1655 onwards he held several offices as a member of the city council and was elected mayor of the town in the year of his death. After his return to Mühlhausen in 1649 he married Anna Maria Wölfer in 1650. Their son Johann Georg Ahle, born in 1650, also made a name for himself as a composer and organist and was active in the field of poetry, like his father. After his father’s death he took up the post of organist at St. Blasius.]

From the English page (here) comes this useful bit of information:

Much of his compositional output consists of sacred choral and vocal works, instrumental music, and organ music. He is best known for motets and sacred concertos (most of them in German, some in Latin) contained in Neu-gepflanzte Thüringische Lust-Garten, in welchem… Neue Geistliche Musicalische Gewaechse mit 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10 und mehr Stimmen auf unterschiedliche Arten mit und ohne Instrument … versetzet (1657–65). He is also known for hymn melodies, of which three remain in the Evangelical Hymn Book.

In point of fact Ahle was very productive and published a great deal during his lifetime. The negligible number of recordings of his works belies the stature he had in his own period as well as the respect given him by modern musicology — he has his own volume in Denkmäler deutscher Tonkunst (aka DDT, Folge 1, Band 5), which says a lot. You don’t get your own volume in DDT unless you’ve got something on the ball. The only recording I find available is the selfsame one I own: selections from Neu-gepflanzte Thüringische Lust-Garten performed by the Bach Collegium Japan under the direction of Maasaki Suzuki with Concerto Palatino contributing the instrumental parts. It’s an excellent recording featuring Japanese countertenor Joshikazu Mera. The CD is available through ArkivMusic (webpage here). It has some stunning sacred concerted motets like Zwingt die Saiten in Chitara and Jesu dulcis memoria.

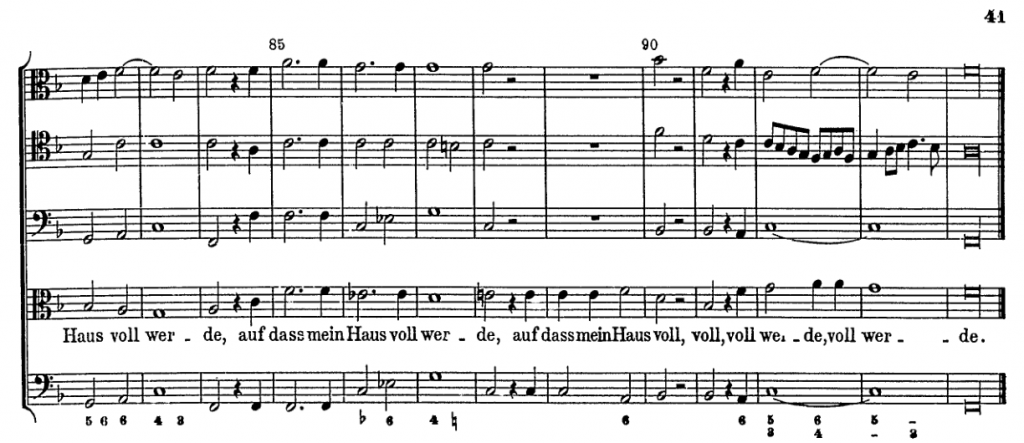

A special place in my own affections goes to the concerted motet Gehe auf die Landstrassen, on the text of Luke 14:23, in the King James Version thus:

And the lord said unto the servant, Go out into the highways and hedges, and compel them to come in, that my house may be filled.

Ahle won me over from the beginning because his music has a special heartfelt quality I find particularly touching. Gehe auf die Landstrassen communicates that heartfelt sense in its fullness. The only available recording of it I know is the one by the Ricercar Consort with the ravishing voice of countertenor Henri Ledroit. You can listen to it on YouTube here. Structurally it follows a pattern Ahle found easy to hand since it occurs in many of this compositions. A chordal section begins the work and is followed by a section of more rapid passagework. The sustained sense of things from the beginning underpins the melismatic passagework, which brings a fine sense of interest to the stately harmonic proceedings. Ahle’s harmonies are where the heartfelt sense comes through most clearly, I think. After much lovely busyness in both the instrumental and vocal lines of Gehe aus, Ahle ends the motet with a chordal section harking back to the one at the beginning, changing from major to minor in a rhythm that seems to catch its breath before ending in the major with a gesture of openness and ease:

Whatever you can find of Ahle’s work is more than worth a careful listen. He’s definitely at the top of my list for the German Early Baroque.

![]()

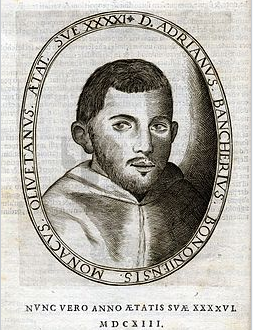

Adriano Banchieri (Italian, 1568-1634)

Dear old Banchieri, what a character. And a priest into the bargain. He’s proof of the fact that not all priests are like Savanarola — dour and concerned only with fire and brimstone. Banchieri is after a good time and plenty of it.

The English and Italian Wikipedia pages on him appear to be roughly equivalent with regard to biographical information so I’m spared the trouble of translation and you can get the dope straight from the horse’s mouth (webpage here):

He was born and died in Bologna (then in the Papal States). In 1587 he became a monk of the Benedictine order, taking his vows in 1590, and changing his name to Adriano (from Tommaso). One of his teachers at the monastery was Gioseffo Guami, who had a strong influence on his style.

Like Orazio Vecchi he was interested in converting the madrigal to dramatic purposes. Specifically, he was one of the developers of a form called “madrigal comedy” — unstaged but dramatic collections of madrigals which, when sung consecutively, told a story. Formerly, madrigal comedy was considered to be one of the important precursors to opera, but most music scholars now see it as a separate development, part of a general interest in Italy at the time in creating musico-dramatic forms. In addition, he was an important composer of canzonettas, a lighter and hugely popular alternative to the madrigal in the late 16th century. Banchieri disapproved of the monodists with all their revolutionary harmonic tendencies, about which he expressed himself vigorously in his Moderna Practica Musicale (1613), while systematizing the legitimate use of the monodic art of figured bass.

To listen to his madrigals you’d think he was a party hearty. The madrigal comedy Barca di Venetia per Padova from 1605 is as close to a musical version of a Groucho Marx film as you can get. Hilarious. But he also buckled down and wrote serious church music, so credit is due him for musical versatility. I expect the ecclesiastical compositions were the way he kept himself out of hot water with the Monsignor after publishing bumptious musical comedies in Venetian dialect.

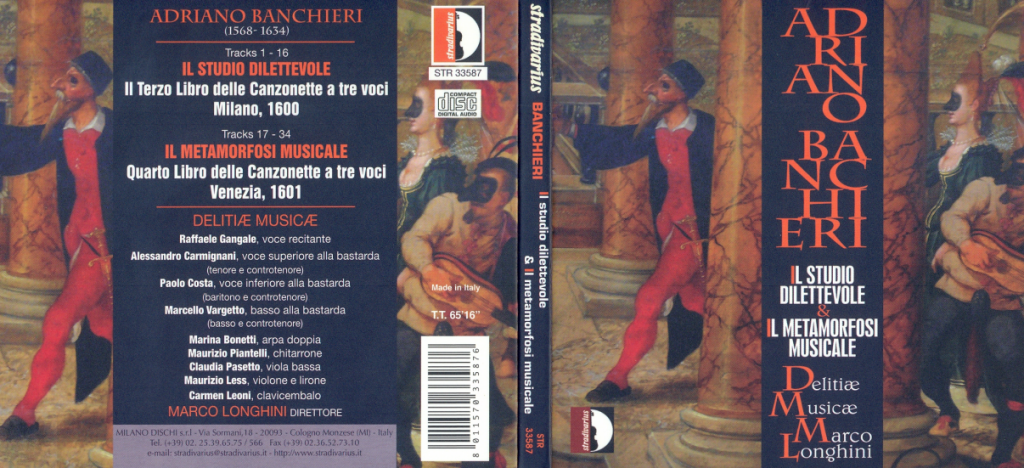

Many recordings of Banchieri’s music are available, both of ecclesiastical music and of the fun stuff. The fun stuff I own is on a recording of Il Studio dilettevole and Metamorfosi by the group Delitiae Musicae directed by Marco Longhini:

The serious stuff I have is on two recordings. The first is the Vespro per la Madonna performed by Gruppo Polifonico Francesco Corradini directed by Fabio Lombardo. The second is a recording of Vezzo di perle musicali, op. 23, sacred motets for soprano(s), released on the Tactus label. You’ll find much more on Amazon — Banchieri may not have reached superstar status but word is obviously out that he’s a good time.

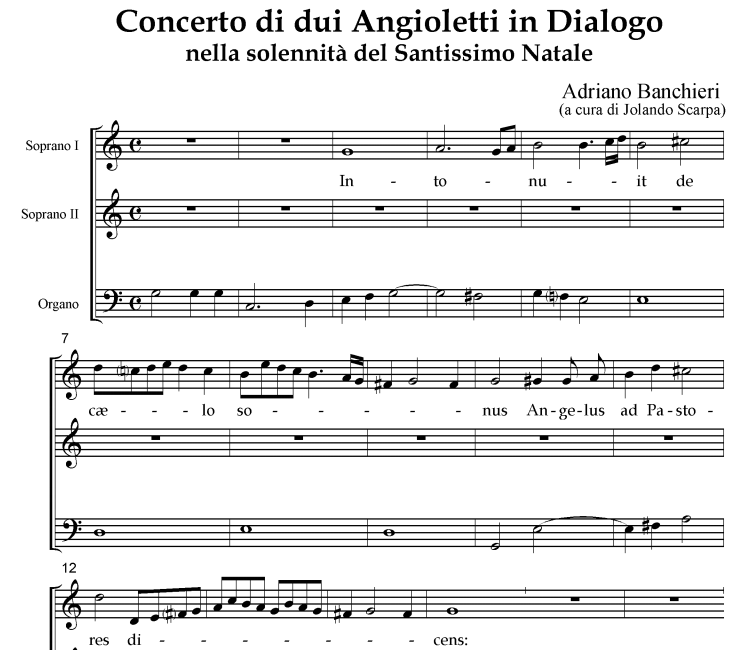

His nature shows best in the madrigals, truth be told. I’ve listen carefully to the ecclesiastical works and come to the conclusion that his heart just wasn’t in it. There can be no doubt that his heart was front and center in the madrigal comedies. They sparkle with inventiveness and slapstick humor. I can easily imagine him sitting at a table in the monastery by candlelight as he writes out his score, giggling while he writes, then dropping the pen while he goes into a belly laugh at the silliness he’s putting down on paper. That’s the real Banchieri. When he writes church music he has the air of an adolescent altar boy trying to stay on task and not look at the girls in the first row of pews. Strain is evident in the minimalist scoring and the (paltry) interaction between music and text. A good case in point is Concerto di due angioletti in dialogo (yes, you read right, two little angels) from the Vezzo di perle musicali. He can’t manage to get more than two bars underway before resorting to a cadence:

But never mind, it’s the madrigals he left us that rocket him to superstar status. You can find a good sampling of his music on YouTube and recordings are a-plenty on Amazon. Go crazy (just like he did LOL).

![]()

Antonio Bertali (Italian, 1605-1669)

AllMusic outshines Wikipedia as a source of biographical information (webpage here):

Antonio Bertali was a hugely influential composer and violin virtuoso whose modern reputation pales in comparison to the fame he achieved in his own lifetime. He was born in Verona in 1605 where he later gained his early musical training at the Cathedral under Stefano Bernardi. In 1662 Bernardi accepted an appointment with the Bishop of Breslau (Wroclaw) and it is often assumed that this Habsburg connection led to Bertali’s appointment in Vienna in 1624. He must have impressed in his early years there, in 1631 he was given the important commission of composing a cantata, Donna Real, for the marriage of the future Emperor Ferdinand III to the Spanish Infanta Anna Maria. He composed numerous other works for special occasions and received several accolades, including being referred to as valaroso nel violino by Giovanni Bertoli in 1645. Following the death of Giovanni Valentini in 1649, Bertali succeeded him as Kapellmeister of the imperial court. During this time Bertali devoted a great deal of attention to promoting Italian opera at the Habsburg capital — to which he made a substantial contribution.

Bertali often composed in a lavish and virtuosic style, featuring highly varied instrumental and vocal textures. The vast number of his manuscript compositions mentioned in the inventory of the Emperor’s private collection (Distinta specificatione) has been lost. Pavel Vejvanovksy, the Moravian Kapellmeister to the Bishop of Olomouc, copied a great number of Bertali’s compositions, and, rather surprisingly, many of these still await scholarly attention and revival.

As his education and background suggest, it is north Italian influences that are most apparent in Bertali’s music. In his vocal music, the influences of Monteverdi and Cavalli are seldom far beneath the surface as is the influence on his instrumental music of his predecessor at Vienna, Valentini. In some works, such as the impressive Vidi Lucirferum and a Salve Regina in G minor, Bertali combines elements of the stylo antico with more modern Italian operatic trends.

As with many other composers of the Baroque period modern recordings skew our perception of the composer by presenting only one facet of his oeuvre. Recordings of Bertali’s oeuvre focus almost entirely on instrumental music — which is stunning, to be sure — but we have little opportunity to know Bertali as a vocal composer. What a pity. Given how good his instrumental music is, I expect he delivered fantastic results in the vocal department, as well.

The instrumental music is thoroughly northern Italian and extremely inventive. Bertali has the gift of writing sophisticated music that speaks very clearly and powerfully emotionally. It’s a different sense than the heartfelt quality of Ahle but equally impressive — he doesn’t hold the emotional cards close to his chest and wow you with his technical brilliance, the brilliance serves the feeling of the piece. That emotional forthrightness is why I consider Bertali a superstar of the Early Baroque, since the period was all about expressing feeling and setting aside the technical conventions that ruled the roost during the Renaissance.

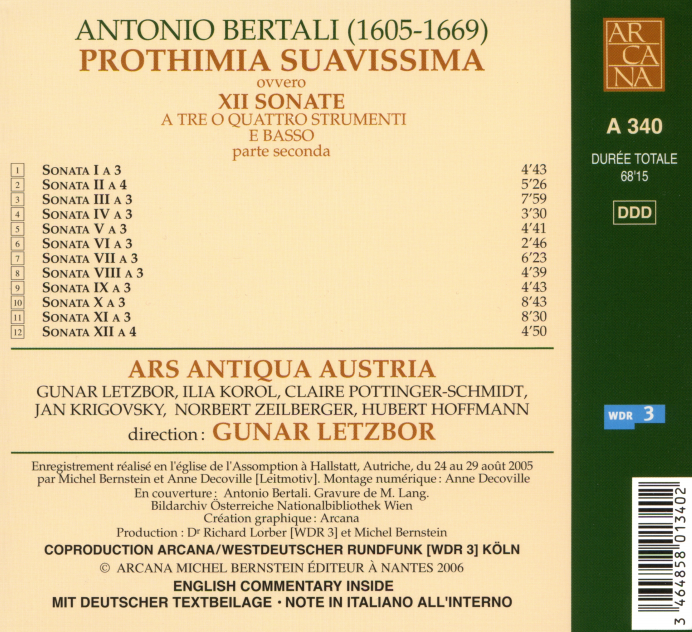

My favorite recording of Bertali’s music is the one of Prothimia suavissima done by Ars Antiqua Austria under Gunar Letzbor. Here’s the CD verso:

Each of the pieces is a world unto itself, as different from the others as chalk from cheese. In the notes to a recording of Biber’s Fidicinium sacro-profanum the venerable René Clemencic commented that in each of the sonatas Biber managed in a few minutes to put forth as much variety of feeling as a Romantic composer did in a symphony. Bertali comes a close second in my opinion. His emotional range is large and he pulls all the stops. His structural refinement brings the thrill of excellence to the connoisseur but even if you’re not up on your stretti or your counterpoint you get the full emotional effect. That’s the main point for Signor Bertali.

Fortunately there are lots of recordings of Bertali’s music on the market. There’s also a good selection on YouTube, including some vocal compositions such as La Strage degli’innocenti, an oratorio. Introduce yourself to Signor Bertali if you haven’t already met him, you’ll find him a most accommodating fellow and boy, does he the have the goods to deliver.

![]()

Samuel Capricornus (Czech/Bohemian, 1628-1665)

I’d be more than happy to call Capricornus a Czech composer, but the reality of the Bohemian Lands in his day was hardly cut-and-dried ethnically and linguistically as is currently the case in the Czech Republic. German was the official language of that part of the Habsburg Empire and there were German-speaking people all over the place. Capricornus was not an ethnic Czech, he was a German who happened to be from Bohemia, where there were Czech people (mostly peasants if the truth be told). So he’s really a German composer and soon enough in his career he landed in Germany where he made his name as a musician. Here’s the skinny from his Wikipedia page (here):

… born Samuel Friedrich Bockshorn (21 December 1628, in Žerčice near Mladá Boleslav – 10 November 1665, in Stuttgart).

Capricornus’ father was a Protestant minister, who fled with his family for fear of the Counter-Reformation to Bratislava in the former Kingdom of Hungary. After completing high school in Sopron, he studied languages and theology in Silesia before becoming a musician at the imperial court in Vienna. Here, he became acquainted with the music of Giovanni Valentini and Antonio Bertali. After a short stay in Reutlingen he worked for two years as a private music teacher in Bratislava and then from 1651 to 1657 he was active as a music director in various churches and as a music teacher at a high school there.

In May 1657 he became Kapellmeister in Stuttgart and soon became engaged in a bitter dispute with the organist of the collegiate church, Philipp Friedrich Böddecker, who had himself coveted the position, and his brother David, a cornetto player. Already in September 1657, David Böddecker had complained about a “high and difficult piece” which he had been asked to play by Capricornus and that he also had to play the “Quart-Zink” (a small, high pitched cornetto) and sing, which were not part of his job requirements. In his defense against these allegations, Capricornus complained about the unruliness, and the “gluttony and drunkenness” of the musicians in the kapell, also saying the cornetto players played their instruments like a cow horn.

Capricornus remained in this post until his death in 1665.

Oops. Temper, temper …

However irascible a figure Capricornus may have been, I gladly set that aside for the sake of his exquisite music. If Ahle’s strong suit is his heartfelt quality, Capricornus takes heartfelt to the level of serious intensity. This is music that will work you over good and leave you feeling changed after the hearing of it. I haven’t listened to any music by Capricornus for months but I only need to think of the solo motet Jesu nostra redemptio to feel the tightness build in my solar plexus. It has a gorgeous introduction and intermedia for solo viola da gamba, then in comes the soprano with an amazing vocal line including gorgia and all manner of plaintive melodiousness. Stunning stuff. I can’t recommend it too highly.

The German Wikipedia page on Capricornus (here) has important information missing in the English page, so let me pull that info in:

Capricornus war ein produktiver Komponist, er schuf Werke nahezu aller Gattungen und gilt als einer der Hauptvertreter des begleiteten Liedes in seiner Zeit. Außerdem trug er in der Übergangszeit zwischen Heinrich Schütz und Johann Sebastian Bach zur Entwicklung des geistlichen Konzerts und der Kantate bei. Seine Werke waren schon zu Lebzeiten als Drucke, sowie als Handschriften weit verbreitet.

[Capricornus was a productive composer, he composed works in nearly all forms and represents one of the major figures of accompanied song in his period. In addition, he contributed to the development of the sacred concerto and cantata forms in the transitional period between Heinrich Schütz and Johann Sebastian Bach. His works were widely distributed as published music and in manuscript even during his lifetime.]

From the liner notes of the sole recording I own of his music comes the news that he sent some of his works to Heinrich Schütz and asked his opinion. Schütz responded positively and encouraged Capricornus to keep writing what he considered very good music. Coming from the likes of Schütz that’s a kudo with a capital K.

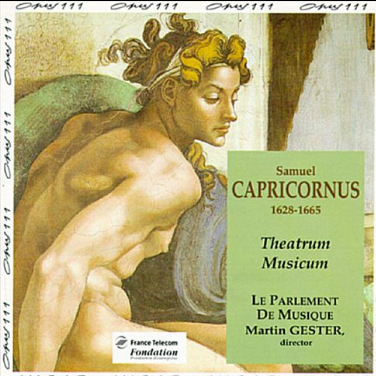

The recording I have is of works from Theatrum musicum (published in Würzburg in 1669) performed by Le Parlement de Musique under the direction of Martin Gester. It’s no longer in print, but happily there are other recordings available in the marketplace, as the ArkivMusik webpage reveals (here).

The Latin texts Capricornus sets to music are worth special comment. I made an MP3 rip of the CD I own and I don’t have the liner notes with me as I wander about the world, but I’ve read the Latin texts closely and recognize their unusual and special character. They’re not from the Bible. Some commentators speculate that Capricornus wrote them himself. They’re devotional outpourings worthy of Teresa of Avila — i.e. intense. To understand the text as it’s sung is crucial in the works of Capricornus because few composers bond music and text so tightly together as he does. The result is gobsmacking and emotionally compelling in a way I find rare among composers of any period. Capricornus deserves superstar status on that basis alone, but he was a consummately gifted composer and ticks all the other boxes a composer should tick.

Why he hasn’t been raised to rockstar status I have no idea. It passeth understanding. All I can do is urge you, nay, implore you, to get your hands on some of his music and listen carefully. It only takes one hearing for the superstar status to become abundantly clear. Capricornus will become one of your steady musical dates, I’m sure. He’s been one of mine since I first heard his music 15 years ago. Go for it.

![]()

Cristofaro Caresana (Italian, 1640-1709)

The Neapolitan School of the Italian Baroque was in its day a Big Deal. If you hit it big in Naples, especially as an opera composer, you had it made in the shade. Those days are long gone, of course, and nobody these days associates Naples with excellence in musical culture. Back in Caresana’s day, however, Naples was ruled by the Spanish and formed a cultural center of major importance. That’s why hitting it big in Naples was a Big Deal.

Biographical information is slim pickings. Here’s the scoop from Caresana’s Wikipedia page (here):

Born in Venice, his precise birthday is not known. After studying under Pietro Andrea Ziani (uncle of Marc’Antonio Ziani) in Venice, he moved to Naples late in his teens, where he joined the theatre company of Febi Armonici which produced early examples of melodrama. Later, in 1667, he became an organist and singer in the Chapel Royal and director of the Neapolitan Conservatorio di Sant’Onofrio a Porta Capuana, one of the famed orphanage-music schools of Naples, until 1690. In 1699 he succeeded Francesco Provenzale as Master of the Treasury of San Gennaro. He wrote music for a number of other Neapolitan institutions until his death in Naples in 1709. Amongst others, the Spanish guitarist and composer Gaspar Sanz studied music theory under his tutelage.

He is remembered for his cantatas, especially for the nativity season as well as instrumental interludes sometimes featuring spatially separated ensembles. His music continues to be played and recorded to the present day and stands as a testament to the quality of this Neapolitan baroque composer.

Please note the last paragraph. I cite it as corroboration for my qualification of Caresana as an Early Baroque Superstar. I’m not the only one who thinks so, obviously. On the other hand, we have the supercilious and irritating opinion of Jonathan Freeman-Attwood in Gramophone (webpage here) as a perfect example of the musicological prejudice that has kept Caresana from recognition as the stellar composer he is. Mr. Freeman-Attwood’s assessment of the situation is, in a word, twaddle:

However persuasively packaged, and despite everything we know about Opus 111’s distinctive product, Caresana’s cantatas are hardly big-time baroque. But he who cocks a snook too hastily forgoes something of a treat. Antonio Florio’s exotic-sounding group, Cappella della Pieta de’Turchini (Turchini means turquoise which was the colour of the tunics of one of Naples’s leading conservatoires at the time) are just the fillip for those who need constant reminding that the musical world revolved more around seventeenth-century Naples than it did the majority of centres who patronized the great composers. This is of course the problem with so much of this underrated and glorious century: not enough Monteverdis, Charpentiers, Buxtehudes or Purcells. Instead, encyclopaedias of ‘worthy’ representatives from forgotten musical meccas who gently guide us through the uncomfortable terrain of hybrid genres, not-quite-established forms and mesmerizing vocal peaks and troughs – and eventually (phew) towards Corelli a few miles up the road.

Excuse me while I wretch uncontrollably for a few minutes … … … OK, back in the saddle. I’m not even going to dignify Mr. Freeman-Attwood’s utterances with commentary. Let’s move on, there’s a bad smell where we’re standing.

The group mentioned above, Cappella della Pieta de’ Turchini directed by Antonio Florio, has been instrumental in recording music from the heyday of the Neapolitan Baroque and the recordings I own are performed by the Cappella. They do wonderful things with Caresana’s music.

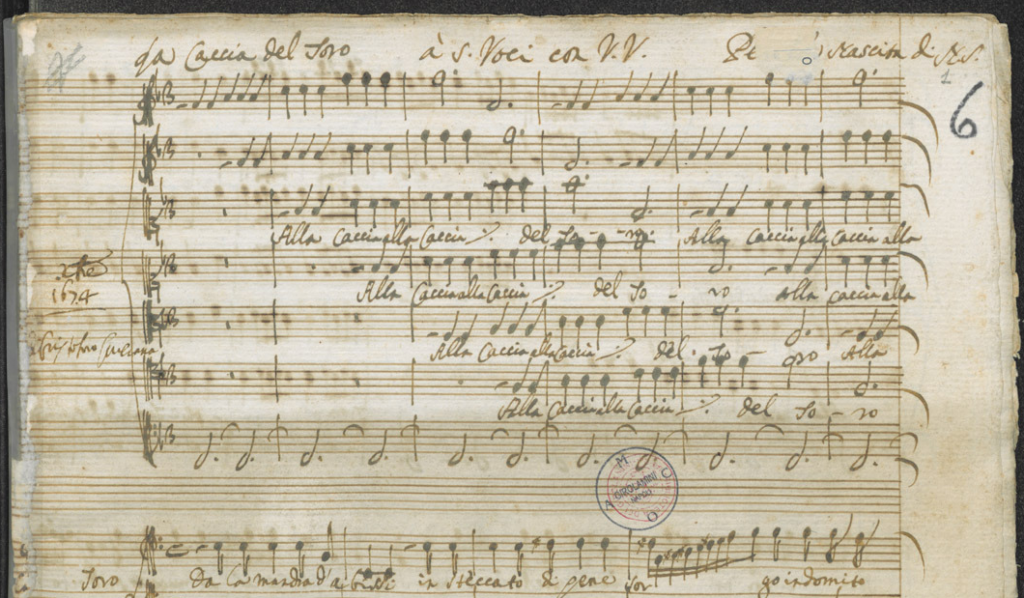

I’m the proud owner of two of Florio’s recordings featuring Caresana: L’Adoratione de’ Maggi and Per La Nascita Del Verbo, the latter of which features some brilliant Christmas cantatas. The most astonishing of the pieces in my opinion is La Caccia del toro, a dramatic cantata that has as much going on in it as a Verdi opera. Here’s a look at the first page of the manuscript:

They get up to all sorts over the cantata’s course, never a dull moment. It’s dramatic vocal writing at its best.

There are precious few recordings of Caresana’s music in the marketplace. He often gets packaged in anthology with other composers of the Neapolitan School, e.g. Francesco Provenzale (who’s always a good listen, too, by the way). You’re far better off going to YouTube for some sampling, where you’ll find some recordings by Florio. Don’t miss the performance of Tarantella available for your listening pleasure here. The tenor, Pino de Vittorio, is quite a character and features in many of Florio’s recording of Caresana’s tongue-in-cheek secular cantatas. Both the music and performance won’t fail to impress, I’m sure.

![]()

Thus we come to the half-way point of our journey. There are five more composers to go, but I’ve gone on long enough for the time being so I’ll be back soon with the rest of the story. In the meantime, happy listening to the five superstars we’ve covered this time. You’ll have more than enough to fill those ears until I get the second half ready to hit the road. Enjoy!