April 2020

It’s worthwhile to consider the fact that power need not necessarily corrupt. It can actually lead to quite other and more laudable expressions of human beingness such as the urge to compose music. This post is an appreciation of eight rulers whose musical gifts were apparent regardless what their political legacy might be. The list includes both men and women, I’m happy to report. If the musical legacy they left was all we had of them that would be more than enough to qualify them for a tip of the historical hat. As we will see, some were more successful in the world of Realpolitik than others, but musically they all deserve our recognition and in some cases our unbridled admiration. I’ll work through the list in historical order from earliest to most recent. I’ve limited myself to rulers who lived through the Classical period. As is always my standard practice I’ll discuss (with one notable exception) only composers whose music I have in my own collection. Here we go, beginning at the beginning.

It’s worthwhile to consider the fact that power need not necessarily corrupt. It can actually lead to quite other and more laudable expressions of human beingness such as the urge to compose music. This post is an appreciation of eight rulers whose musical gifts were apparent regardless what their political legacy might be. The list includes both men and women, I’m happy to report. If the musical legacy they left was all we had of them that would be more than enough to qualify them for a tip of the historical hat. As we will see, some were more successful in the world of Realpolitik than others, but musically they all deserve our recognition and in some cases our unbridled admiration. I’ll work through the list in historical order from earliest to most recent. I’ve limited myself to rulers who lived through the Classical period. As is always my standard practice I’ll discuss (with one notable exception) only composers whose music I have in my own collection. Here we go, beginning at the beginning.

![]()

Henry VIII, King of England (1491-1547)

Quite apart from having a way with the ladies — in a manner of speaking 🙂 — Henry was a musician of acknowledged accomplishment. For our purposes we may blithely (and with a sigh of relief) set aside all the other things for which the monarch is known. In that regard I think less of wives hitting the chopping block than I think about the dissolution of the monasteries — hundreds of years of art and architecture lost forever due to the recalcitrance of a single female reproductive tract. Better that we should leave the sociopolitical and the biological aside and just focus on music, don’t you find?

David Skinner in an article entitled “The Musical Life of Henry VIII” (here) gives us an excellent overview of the monarch’s musical accomplishments and predilections:

But what of Henry’s own music-making? It is well known that he was a competent player of a variety of keyboard, string, and wind instruments and there is even an image of him playing his harp in the so-called Henry VIII Psalter. According to Sir Peter Carew, a Gentleman of Henry’s Privy Chamber, the king was also ‘much delighted to sing’. We learn, too, from the chronicler Edward Halle that Henry was an accomplished composer, having set at least two masses in five parts which ‘were song oftentimes in hys chapel, and afterwardes in diverse other places’. The main testament to his compositional skill, however, is the so-called Henry VIII Manuscript, which contains 109 songs and instrumental pieces by composers attached to the court as well as some by foreign musicians. No fewer than 33 of the compositions, nearly a third of the entire collection, are ascribed to ‘the kyng h.viii’.

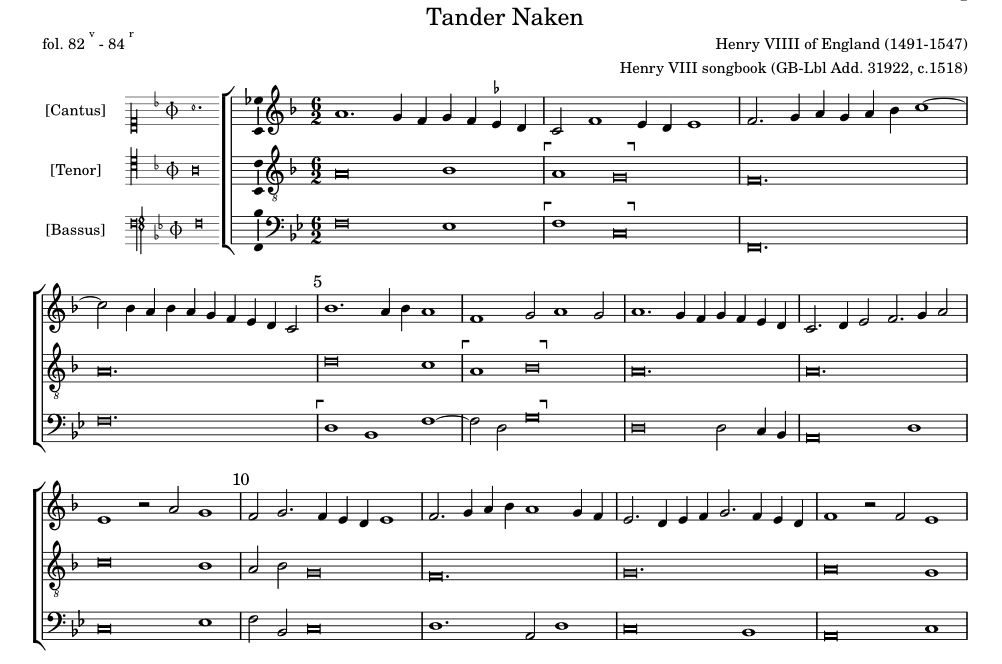

Music scholars often bash Henry’s compositions. True, several are weak: open chords, parallel fifths and other schoolboy errors abound. But all of his surviving works would have been composed when he was in his early twenties, teens or even earlier. If only those five-part Mass settings had survived, we would then have some measure of Henry as a serious composer. One can imagine that he gained advice from composers and musicians attached to his chapel and court, but these early errors seem to show that much of what survives is the king’s own. Of the 13 untexted works, Tandernaken is arguably his most accomplished, but there are other gems.

Most famous in the collection, Pastyme with good companye is similar to Though some saith in which he proclaims ‘I hurt no man, I do no wrong; I love true where I did marry.’ Other compositions, such as Adieu madame and O my heart, seem, meanwhile, to have been conjured from the depths of Henry’s emotions and vividly reveal a young king in love. Now this is good stuff. In celebration of 500 years since Henry came to the throne, perhaps it is time to give his musical side another chance, remembering that without Henry’s actions (good or bad) England’s musical heritage would most likely be different to that which we enjoy today.

Not a bad showing for a Renaissance monarch who had plenty of other things on his plate. It’s understandable that music should have occupied him especially in his youth, since the work of statecraft (and reproduction) absorbed the bulk of his attention in later years. The piece mentioned in Skinner’s article as his most accomplished, an instrumental setting of the tune Tandernaken, performed by the Folger Consort, can be heard on YouTube here. Here’s the first few bars of the score:

It must be said that for someone who as a teenager composed five-part mass settings (if the rumors are true) a three-part setting of a dance tune can’t have been particularly challenging. It’s pleasant but Tielman Susato or Michael Praetorius needn’t worry about losing gigs to the competition. One is reminded in this particular instance of musical monarchy of Dr. Johnson’s comment about dogs who dance on their hind legs — one is astonished to see it done at all. So hats off to old Henry for his musical contribution to Western civilization. Would that it were ample enough to make up for all those destroyed monasteries …

![]()

Moritz, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel (German, 1572-1632)

He has his own Wikipedia page (here) from which comes this info:

English strolling players (‘Die Englische Comoedianten’) were frequent visitors to, and performers in, towns and cities in Germany and other European countries, including Kassel, during the 16th and 17th centuries. Landgraf Moritz (to use his German nomenclature) was a great supporter of the performing arts and even built the first permanent theatre in Germany, named the Ottoneum, in 1605. This building still exists today but as a Natural History Museum.

Maurice’s actions (though not necessarily the Ottoneum) ruined Hesse-Kassel financially. In 1627 he abdicated in favour of his son William V. Five years later he died in Eschwege. He was not only a serious musician but an expert composer (a Pavane of his, for the lute, has several times been recorded by both lutenists and guitarists). The leading musical figures whom he supported included Heinrich Schütz and John Dowland.

The support he gave Schütz was to send him to Italy to study with Giovanni Gabrieli. Just think for a moment how different music history of the early Baroque would be if that had never happened. So Moritz should be given due credit for bringing Italian seconda prattica to northern Europe since Schütz was chief among its primary vehicles of transport. Let’s have a warm round of applause for Landgraf Moritz on that account, shall we?

Recordings of Moritz’s compositions are not easy to come by. The pavane mentioned in the citation above is available in YouTube here. There’s also an imposing six-part Intrada available here. Just for kicks you can compare Moritz’s composition with those of William Brade, one of the English “strolling players” mentioned in the citation. It’s easy to see who influenced whom.

![]()

Paul I, Prince Esterházy of Galántha (Hungarian, 1635-1713)

The name of Esterházy is so associated in our minds with Haydn that it may well come as a shock to more than me that the principal proponent of the House at a date well before Haydn was himself a fine composer. His political and military accomplishments were also quite impressive as was the indefatigable nature of his loins, since he had 26 children by two wives, a reproductive legacy that seems exclamatory in the extreme. The quality of his humanity may be judged from the report of this act given in his Wikipedia page (here):

In 1671, he rescued some 3,000 Jews who had been expelled by Leopold I, Holy Roman Emperor from Vienna. This led to their resettlement as tenant farmers and the founding of the Seven Municipalities (German: Siebengemeinden) on Esterházy lands throughout Burgenland.

It was Paul I who transformed the Esterházy family seat from a medieval castle into a Baroque palace. It’s an exquisite piece of Baroque architecture, as you can see in these pics:

Small wonder Haydn chose to serve at the Esterhazy Court for nearly 30 years. He couldn’t have done better as far as real estate goes — and after all, even famous composers need digs, right?

Paul I was a man of many talents and accomplishments, such that it would be difficult to rank them in order of importance. As a composer he certainly doesn’t figure at the top of the list among the renowned composers of his day — unsurprising when one considers that his day included the likes of Biber, Schmelzer, Bertali and others of equally stellar stature. That said, Paul I deserves the credit due him as a composer. Had he figured in history only as a musician rather than a competent ruler he would still deserve a place in the annals as a minor but interesting composer of the period.

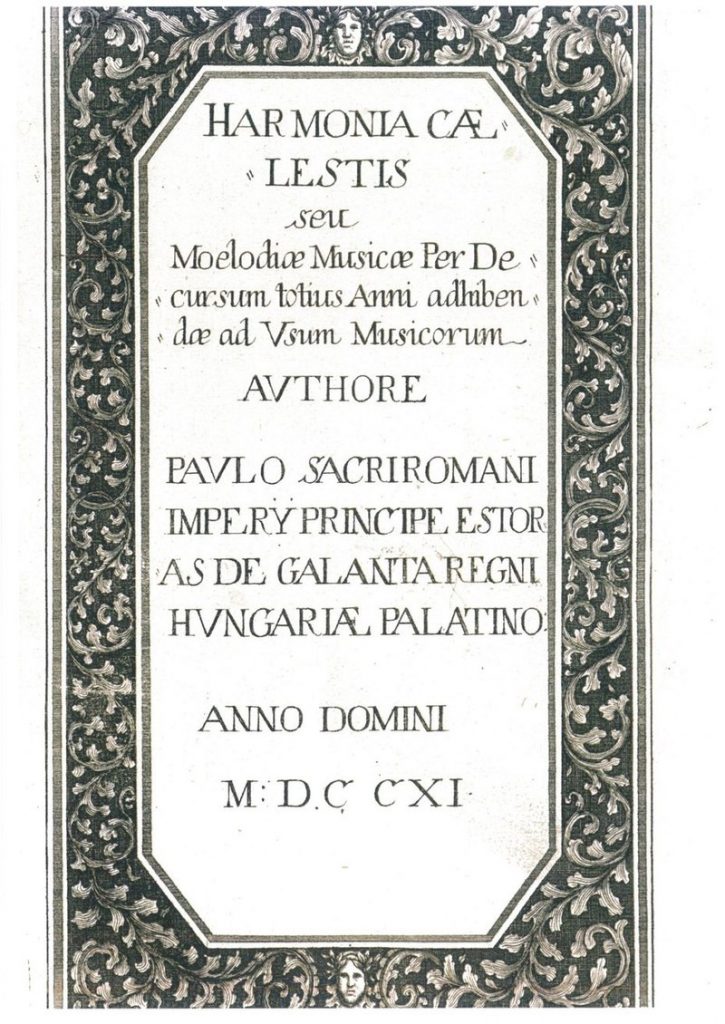

His main claim to fame is the collection of 55 cantatas entitled Harmonia Caelestis:

There it is set forth before you: Palatine Prince of the Holy Roman Empire. He’s the Real Deal. The best recording of works from the collection IMHO was done by Capella Savaria under the direction of Pál Németh, with the fine soprano Mária Zádori in the list of vocalists. There are several excerpts from the recording available on YouTube and it’s still available on Amazon. About the music itself let me just say this: after listening to it I find it easy to understand why Paul I rescued 3,000 Jews after expulsion from Vienna. Have a listen yourself and see what you think.

![]()

Joseph I, Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire (Austrian, 1678-1711)

This fellow is the ne plus ultra of musical monarchy — an Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire. The next step up the ladder is The Almighty Himself. Just ask the Hapsburgs, they’ll sort you out on that point. The word “Habsburg” will elicit various responses in various people. For some it will recall the glory of empire, the stunning wealth and its manifestations to be seen throughout the Habsburg lands. For others it will bring into the nostrils the stench of empire as it rotted away over centuries and sank ever lower in its competence and relevance to the lives of the people who lived under its yoke. Rebecca West counts among the latter. In the epilogue of her monumental work Black Lamb and Grey Falcon she comments on the Habsburgs while discussing the problematics of empire throughout human history:

This family, from the unlucky day in 1273 when the College of Electors chose Rudolf of Habsburg to be King of the Romans, on account of his mediocrity, until the abdication of Charles II, in 1918, produced no genius, only two rulers of ability in Charles V and Maria Theresa, countless dullards, and not a few imbeciles and lunatics.

OK, Rebecca, now tell us how you really feel. 🙂 As a counterpoint I offer this information about Joseph I from the habsburger.net site (here):

Even in his appearance Joseph was not a typical Habsburg: he had escaped inheriting the classic features that occurred frequently in the dynastic bloodline, most notably the prognathic jaw accompanied by the fleshy ‘Habsburg lip’. Contemporary accounts describe the crown prince as unusually handsome. His personality also differed markedly from his forebears: Joseph had a far more self-assured, cosmopolitan demeanour than his deeply religious or even bigoted predecessors, who effaced their personalities behind their imperial office.

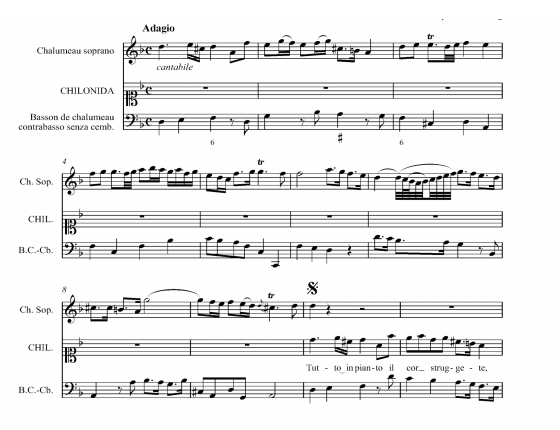

Since we’re dealing with music we may exempt ourselves from judgment about Joseph’s political acumen and accomplishments. I do that happily because his music is fantastic, as anybody with any sense can tell from listening to his aria “Tutto in pianto il cor struggete” (1709) in an excellent performance by the Capricornus Ensemble of Basel available on YouTube here. Not only is it very good music, it’s cutting edge because it uses as the solo instrumental voice the chalumeau, an early clarinet that was just becoming fashionable at the time. Elizabeth Crawford wrote a PhD thesis for her degree at Florida State University entitled The Chalumeau in Eighteenth-Century Vienna: Works for Soprano and Soprano Chalumeau (pdf here). Luckily it contains an incipit of Joseph’s aria:

Thanks, Elizabeth, just the ticket!

The musical Joseph has become completely lost among the doings of the Emperor — it’s very hard to find scores of his music or detailed information about his compositional activity. The compositional structure is that Baroque favorite, the aria da capo. Apparently Joseph composed a number of Italian arias of the same type that were inserted as intermezzi in operas put on by composers of the Court — including Giovanni Bononcini, said to have had the greatest musical influence on the Emperor. The musical meaningfulness of Joseph’s arias should give them the same rank as the works of Jan Dismas Zelenka, with whose music they share a number of characteristics. In fact, if you passed off Joseph’s aria to me as one by Zelenka I’d probably fall for it. It’s that good — and trust me, Zelenka is to me as a god among composers, so that’s saying something. If you want to compare the two I suggest using Zelenka’s duetto “Santo amor, que tanto peni” from Gesu al Calvario (available on YouTube here), which likewise uses a solo chalumeau. Mind you, Joseph apparently has a few bumps along the way that would raise professional eyebrows, but hey, what’s a couple of parallel octaves among friends, especially if you’re Emperor of the Holy Roman Empire? We don’t want to commit lèse-majesté, now, do we. Of course not. Perish the thought. 🙂

![]()

Unico Wilhelm Rijksgraaf van Wassenaer Obdam (Dutch, 1692-1766)

Let’s start with some information from Van Wassenaer’s Dutch Wikipage (here) to set the scene:

De bestuurder Van Wassenaer was muzikaal zeer getalenteerd, maar liep daarmee niet te koop, omdat dat in zijn aristocratisch milieu niet als een bijzonder passende bezigheid werd beschouwd. Daardoor werd het mogelijk dat door hem geschreven stukken aan anderen werden toegeschreven. Hij was componist van de Concerti Armonici die hij schreef tussen 1725 en 1740. Deze concerten werden gepubliceerd in 1740 door de Italiaanse violist Carlo Ricciotti (1681–1756), aan wie de concerten aanvankelijk werden toegeschreven. Van Wassenaer is daarom ook wel “the mystery composer” genoemd.

De Poolse componist François [Franciszek] Lessel (1780?-1835) schreef de concerten ten onrechte toe aan Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. De stijl van de concerten is namelijk Italiaans, volgens Romeinse traditie geschreven met vier vioolpartijen en elk bestaat uit vier delen in plaats van de Venetiaanse drie delen, wat destijds gebruikelijker was; ze zijn vergelijkbaar met het werk van Pietro Locatelli. In 1979 werd een handschrift gevonden van de zes concerten in de archieven van Kasteel Twickel, met het opschrift Concerti Armonici. Hoewel er geen muziekhandschrift van Van Wassenaer zelf werd gevonden, bevat het de gedrukte partituur met een handgeschreven inleiding van Van Wassenaer, luidend: “Partition de mes concerts gravez par le Sr. Ricciotti” (partituur van mijn concerten, gedrukt door Dhr. Ricciotti). Onderzoek van de musicoloog Albert Dunning heeft vervolgens op overtuigende wijze aangetoond dat de Concerti Armonici van de hand van Van Wassenaer zijn.

[… Van Wassenaer was musically gifted but made no show of it since in his aristocratic milieu such a thing was not considered a desirable trait. That circumstance opened the possibility of his works being attributed to other composers. He was the author of the Concerti Armonici, which he wrote between 1725 and 1740. These concertos were published in 1740 by the Italian violinist Carlo Ricciotti (1681–1756), to whom the concerti were at first attributed. Van Wassenaer is rightly known as “the mystery composer.”

The Polish composer François [Franceszek] Lessel (1780?-1835) wrongly attributed the concerti to Giovanni Battista Pergolesi. The style of the concertos is clearly Italian, follows Roman tradition with its writing for four string parts in four movements rather than the more common three of Venetian practice; they are similar to the works of Pietro Locatelli. In 1797 a manuscript of the concertos came to light in the archives of Castle Twickel with the title Concerti Armonici. Although no original manuscript by Van Wassanaer himself has been found, the printed work [at Castle Twickel] has a notation by Van Wassenaer saying “The score of my concerti engraved by Sr. Ricciotti.” Research by the musicologist Albert Dunning has shown convincingly that the Concerti Armonici are from the hand of Van Wassenaer.]

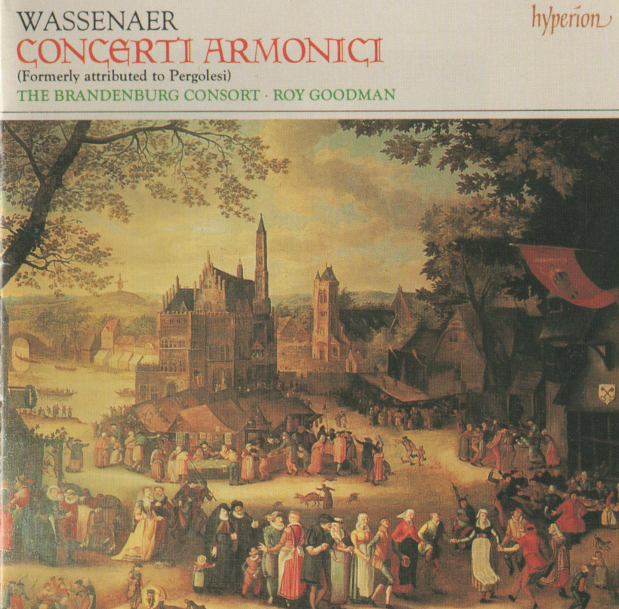

If someone mistakenly attributes your composition to Pergolesi and a musicologist suggests that your works are similar to those of Pietro Locatelli, then you’ve made the grade, babes. Oh yes indeedy. So we need discuss no further the quality of Van Wassenaer’s compositions. Nor do we need to detail the highways and byways he trod as a composer — he was Italianate to the point of being identifiable as belonging to the Roman tradition rather than the Venetian. From the English Wikipedia page on Van Wassenaer (here) comes this little chestnut:

Concerto Armonico No. 2 in B flat Major (Allegro moderato) was among the works that formed the basis for Igor Stravinsky’s Pulcinella, Tarantella, based on works considered at the time to be by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi.

If you can pull the wool over the eyes of Igor Stravinsky I’d say you’ve rather more feathers in your cap than you need, wouldn’t you say?

The recording of the Concerti armonici in my collection was done by The Brandenburg Consort led by Ray Goodman. Here’s the cover:

“Formerly attributed to Pergolesi” — why that particular point was deemed necessary for the cover escapes my understanding. Let’s give over and just stick to the facts: these are concerti by Unico Wilhelm, a Rijksgraaf of the Holy Roman Empire, and they’re good on their own merit regardless to whom they may have been attributed in the past. Seems fair, doesn’t it? Credit where credit is due, isn’t that how the saying goes?

![]()

Maria Antonia, Princess of Bavaria, Elector of Saxony (German, 1724-1780)

I wrote about Maria Antonia in the post “Women Composers Before 1800” so I’m revisiting territory already covered, but the Duchess is interesting enough that I needn’t repeat myself. I’ll add information, a task easy enough considering the ample accomplishments of the woman.

Once again we’re pretty high up on the totem pole since Maria Antonia’s title throughout her lifetime was “Her Serene Highness.” Not exactly something you’re used to saying to somebody when you head down to Safeway to get milk, is it. Born in Munich as Maria Antonia Walpurgis Symphorosa von Bayern (quite a mouthful), her father was Karl Albrecht of the House of Wittelsbach, at the time of her birth Prince-Elector (Kurfürst) of Bavaria but later Holy Roman Emperor under the name Charles VII from 1742 until his death in 1746. Her mother was the Austrian archduchess Maria Amalia, daughter of Emperor Joseph I and his wife Wilhelmine Amalia von Braunschweig-Lüneburg. We’ve dealt with Maria Antonia’s gramps up above, which leads one to consider that music might well have been in the family, since Joseph I was himself so good a composer.

She was the beneficiary of an excellent education, something not necessarily a given if one happened to be female in the 18th century, even if one happened to be a princess. But Maria Antonia had an ace in the hole, as her German Wikipedia page (here) explains:

Als älteste und damit unter den europäischen Fürsten für eine Heirat begehrte Tochter des Paares war sie von Anfang an von politischer Bedeutung und genoss eine standesgemäße Erziehung, zu der auch Malerei, Poesie sowie das Erlernen von Instrumenten gehörte.

[As the eldest daughter of her parents and consequently considered the most desirable marriage prospect by European princes, she was from the beginning of political importance and enjoyed an upbringing corresponding to her station, in which figured painting, poetry and the playing of instruments.]

In the post on women composers I suggested that Maria Antonia deserved the moniker “Supermom” due to her producing nine children and acting for five years as regent for her son, Friedrich Augustus, who became king in 1768. But she’s also up for the “Captain of Industry” badge because — for reasons which only puzzle me tbh — she founded a textile fabric in 1763 and a brewery (!) in 1766. Go figure. I suppose it involved nothing more than money and a signature, but all the same, Her Serene Highness owning a brewery?? Never a dull moment with these poshos, is there …

The musical milieu in which Maria Antonia did her thing was posh in the extreme. When she was just a young thing she had instruction in composition from none other than Nicola Porpora, one of the great Neapolitan opera composers. After her marriage and her move to the Court at Dresden she hobnobbed with the likes of Johann Adolph Hasse, an opera composer who had spent many years in Italy before being convinced by the offer of an astronomical salary to become Kapellmeister at the Dresden Court — although he still spent much of his time in Italy carrying on his business there. His fame at the time could be compared to that of Michael Jackson in ours. Personally I think he was a twat because of what happened at the Dresden Court to Jan Dismas Zelenka, but that’s another story. Maria Antonia studied with Hasse (of course) and the bel canto style for which Hasse was famous influenced her own style considerably.

This list of her works comes from the German Wikipedia page:

Ein ausführliches Quellen- und Werkverzeichnis (handschriftliche und gedruckte Noten und Texte) enthält Christine Fischers Buch Instrumentierte Visionen der Macht. Maria Antonia Walpurgis’ Werke als Bühne politischer Selbstinszenierung (2007).

- Opern:

- Il trionfo della fedeltá (unter Assistenz von Hasse und Metastasio), Uraufführung im Sommer 1754 in Dresden. Textdruck. Notendruck (3 Bände) Breitkopf, Leipzig 1754

- Talestri, regina delle Amazzoni auf ein eigenes Libretto, Uraufführung am 6. Februar 1760 oder 1763 in Nymphenburg. Textdruck. Notendruck (3 Bände) Breitkopf, Leipzig 1765. Das Libretto wurde auch von anderen Komponisten wie Giovanni Battista Ferrandini (möglicherweise um 1760), Johann Gottfried Schwanberger (1764) und Domenico Fischietti (1773) vertont.[3]

- Sonstige Werke:

- Text für das Oratorium La conversione di S. Agostino von Hasse, 1750. Eine deutsche Fassung als Sprechdrama mit dem Namen Der bekehrte Augustinus erschien 1753 und 1766 in der Geistlichen Schaubühne des Ulmer Augustiners Peter Obladen.[4]

- weitere Texte für Kantaten von Hasse, Manna und Ristori

- musikalische Beiträge zu zahlreichen Arien, Pastoralen, Intermezzi, Meditationen und Motetten

- Briefwechsel mit Friedrich dem Großen

The main bits are of course the two operas, Il trionfo della fedeltá and the one that gets the most press, Talestri, regina delle Amazzoni, for which she composed not only the music but the libretto, as well. The recording of it I own is by the Batzdorfer Hofkapelle in a live performance. I don’t find it on Amazon but you can hear excerpts on YouTube. It’s a full-on bel canto affair, no doubt about it — something of which her teacher Hasse must have been proud. All that and still time to carry on a correspondance with Frederick the Great, goodness me …

Good on ya, Your Serene Highness! Let’s hear it for SuperPrincess! You nailed it, babes. 🙂

![]()

Anna Amalia von Braunschweig-Wolfenbüttel, Duchess of Sachsen-Weimar und Eisenach (German, 1739-1807)

(The portrait is, by the way, by Angelika Kauffmann, the renowned Swiss painter who worked in London for many years and became one of only two female members of the Royal Academy.) I have something of a soft spot for Anna Amalia because I lived in Wolfenbüttel for two years and know its history well. Since Wolfenbüttel suffered no damage during World War II I expect many of the historic buildings I saw were at one time before Maria Amalia’s eyes, as well. The Ducal Palace in Wolfenbüttel is a pokey thing, truth be told, so she probably thought when she arrived in Weimar after her marriage that the move was upmarket, not the reverse.

She outdid Maria Antonia with regard to regency: she was Regent for her son Karl August from 1759 to 1775, a total of 16 years. Scant wonder that once shot of the responsibility of statecraft Anna Amalia wanted nothing more than to follow her aesthetic predilections. And she had good company, as the English Wikipedia page (here) makes clear through some strategic name-dropping:

As a patron of art and literature she drew many of the most eminent men in Germany to Weimar, including Johann Gottfried Herder, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Friedrich Schiller and Abel Seyler’s theatrical company. When Anna Amalia succeeded in engaging the Seyler Company, this was “an extremely fortunate coup. The Seyler Company was the best theatre company in Germany at that time.”[2]Amalia von Helvig was also later to be a part of her court. She hired Christoph Martin Wieland, a poet and translator of William Shakespeare, to educate her son. She also established the Duchess Anna Amalia Library, which is now home to some 1,000,000 volumes. The duchess was honoured in Goethe’s work under the title Zum Andenken der Fürstin Anna-Amalia.

Anna Amalia was a notable composer. Among her significant works is a symphony for two oboes, two flutes, two violins, and double bass (1765), a tripartite oratorio (1768), an opera called Erwin und Elmire (1776), based on a text by Goethe, and a divertimento for piano, clarinet, viola, and violoncello (around 1780).

Her search for personal artistic satisfaction led to the extreme step of moving to Italy for two years, as the German Wikipedia page (here) tells us:

Die wichtigsten Künste für Anna Amalias persönliche Kunstliebhaberei und die Geselligkeit ihres Hofes waren aber Musik und Musiktheater. Die Herzogin bedauerte, dass Weimar hierin gegenüber den künstlerischen Zentren des Reichs relativ abgekoppelt war. Diese fehlende persönliche Erfahrung suchte sie vor allem in Italien aufzuholen. Die Jahre 1788 bis 1790 verbrachte sie in Rom und Neapel, was für eine verwitwete protestantische Fürstin sehr ungewöhnlich war. Dort erfreute sich Anna Amalia an Natur, Künsten und Sehenswürdigkeiten, führte eine musikalische Académie (Salon) und genoss eine geheime Freundschaft zu Giuseppe Capecelatro, dem Erzbischof von Tarent.

[The most important arts for Anna Amalia personally and for the company of her court were music and musical theater. The Duchess regretted the fact that Weimar in regard to those arts was relatively marginalized in comparison to the cultural centers of the Empire. She attempted to compensate for that lack of personal experience by going to Italy. She spent the years from 1788 to 1790 in Rome and Naples, a very unusual thing to do for a widowed, Protestant princess. In Italy Anna Amalia took pleasure in Nature, the arts and sightseeing, led a musical salon and enjoyed a secret friendship with Giuseppe Capecelatro, the Archbishop of Tarento.]

You see from this information that Anna Amalia was a woman of spirit who knew her own mind. Once her state duties were absolved by the accession of her son to the throne she became the kind of woman we associate with the Paris salons. It was all about intellect, music and literature. Kudos to her for hightailing it out of futzy old Weimar to Italy for a couple years — I’d have done the same myself. The soft spot I have for her stems not only from her being a Wolfenbüttlerin but also from being a person I think it would have been wondrous fun to know. Imagine the discussions that took place among her and her friends. They must have been fascinating. And just think, nobody on their phone playing Angry Birds while you’re trying to carry on a conversation. 🙂

I own a performance of Anna Amalia’s opera Erwin and Ermine and it’s great. She was a good composer and deserves a high five. There are excerpts of the opera available on YouTube. I’d suggest you also have a listen to a performance of the Allegro from the Divertimento for Piano, Clarinet, Viola and Cello (available here). Very cheerful and quite the jaunty tune, I must say. Doff of the hat to the Duchess!

![]()

Frederick the Great, King of Prussia (German, 1712-1786)

I know it’s not nice to say but he looks like somebody’s great-uncle who’s been hitting the bottle pretty hard across the years. To give the guy a break, he had a hard life — and it shows.

We’ve all heard about the musical proclivities of Frederick the Great — those of us who have had much truck with music from the Baroque period, in any case. It’s common knowledge that he played the flute, had Johann Joachim Quantz as his teacher, gathered a coterie of famous musicians around him at his Court, including C.P.E. Bach. We’ve all heard the story of Old Bach’s visit to Potsdam and the genesis of the Goldberg Variations. What’s left to tell?

It’s probably best to let the hand of silence slip before my mouth before I go any further. I’m not a fan of Old Fritz’s music tbh. Some of the descriptive words that come to mind are stodgy, formulaic, uninspired, predictable … you get the drift. The thing that interests me most about this particular musical monarch is the bevy of geniuses he collected for his musical court. Here’s a good listing from an article on the Deutsche Welle website (here) entitled “Komponist und Bach-Fan: Friedrich II.”:

Bald nach seinem Regierungsantritt ließ Friedrich II. die Staatsoper Unter den Linden in Berlin bauen und holte einige prominente Musiker an den Hof: seinen einstigen Flötenlehrer Johann Joachim Quantz sowie Carl Heinrich Graun, die Brüder Franz und Georg Anton Benda und Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. Die Residenzen Berlin und Potsdam wurden damit Zentren des deutschen Musiklebens.

[Soon after his accession to the throne Frederick had the Staatsoper Unter den Linden built and brought to his Court some prominent musicians: his former flute teacher Johann Joachim Quantz as well as Carl Heinrich Graun, the brothers Franz and Georg Anton Benda and Carl Philipp Emanuel Bach. The residences in Berlin and Potsdam thus became centers of German musical life.]

I own recordings of works by all the composers named. I own not a single recording of music by Frederick himself. The reputations of C.P.E. Bach, Carl Heinrich Graun and his brother Johann Gottlieb (one of the best composers of instrumental music of the 18th century IMHO) and the Benda brothers are secure and require no comment. You can find an embarrassment of riches for listening on YouTube for all of them.

Frederick’s accomplishments extend into the domains of literature, as well — one thinks of his famous correspondance with Voltaire and the latter’s visits to Potsdam that ended up on such a sour note. But let’s be clear: Frederick was first and foremost a king. That his musical inclinations were native stands beyond question, but the way in which he manifested them is 100% royal: my way or the highway. The geniuses he collected around him weren’t treated as geniuses, they were treated as soldiers to be deployed in whatever strategy suited His Majesty’s musical battle plan. The same happened in the literary domain with Voltaire, who got tired of it and finally left as Joshua Figueroa explains in an article on the website of KMFA89.5 (here):

For a time, Voltaire and Frederick’s relationship in Potsdam was mutually beneficial. Through Frederick’s public admiration, Voltaire was given a status few other philosophers of the era had. Likewise, Voltaire helped spread the word of Frederick’s flattering image as a philosopher-king.

Unfortunately, Potsdam just wasn’t big enough for the two of them. While Voltaire enjoyed the praise and luxuries that came with being a member of the king’s court, at the end of the day his job was mostly just to proofread and even rewrite Frederick’s awful attempts at French poetry. That and have dinner with him. This mundane way of life suited Voltaire for awhile since it gave him a lot of time to work on his own writings, but eventually it was just too limiting for him. In speaking candidly about his proofreading position, Voltaire said “Will he never get tired of sending me his dirty linen to wash?”

The stories are rife about Frederick’s court musicians bending tempos to match those of the King as he failed to keep steady time playing his way through a composition. Given the vast chasm in both accomplishment and sensibility between Frederick and the musicans he employed it’s no wonder many of them ended up leaving. Who’d want to put up with that tiresome business?

I don’t listen to Frederick’s music but I do thank him for giving genius a job. The composers associated with his Court are among the best of the century. As the supporter of that genius Frederick gets a high five from me.

![]()

And there we have our tour of musical monarchs and other rulers who wrote music. If you asked me to pick my favorite I’d have to say it’s Joseph I — that aria “Tutto in pianto il cor struggete” is a tune I can’t get out of my head after I listen to it. But the two Marias wrote great stuff, too, and I’d be sorry to leave them off the “best of” list. As for being an all-round great guy in addition to a good ruler and composer, Paul I Esterhazy would take the cake, I think. But each of the rulers has his or her strong points, so let’s give everybody a prize, shall we?

I’m grateful to these rulers for redeeming political power — all too often sullied with barbarity — with the healing balm of music. May their works remind us all that not every ruler is insensible to the notion that power and art can be powerful partners each of the other. Vivat rex, vivat princeps and vivat musica!