September 2018

Yesterday I got the Kindle version of a book I read a few years ago, The Sixth Extinction: an Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert. It made a very strong impression on me when I first read it and many bits of information I gathered from it stayed with me over the years since the first read. Recent research I’ve done on the Sixth Mass Extinction (hereafter SME for short) brought me back into contact with Kolbert’s work and I was delighted to find a Kindle version of her book. Without a moment’s hesitation I punched the button and voila, there it suddenly was on my device, just like magic. Would that it were possible to deal so easily with the environmental problems Kolbert describes.

Yesterday I got the Kindle version of a book I read a few years ago, The Sixth Extinction: an Unnatural History by Elizabeth Kolbert. It made a very strong impression on me when I first read it and many bits of information I gathered from it stayed with me over the years since the first read. Recent research I’ve done on the Sixth Mass Extinction (hereafter SME for short) brought me back into contact with Kolbert’s work and I was delighted to find a Kindle version of her book. Without a moment’s hesitation I punched the button and voila, there it suddenly was on my device, just like magic. Would that it were possible to deal so easily with the environmental problems Kolbert describes.

Kolbert won the Pulitzer Prize for her book, which is as much of a recommendation as anyone needs, I suppose. It’s an easy read, she’s the Garrison Keillor of the Bad News Brigade, making the hair-raising circumstances she reports seem only half as bad by the calm and chatty presentation. Anybody who wins the Pulitzer Prize of course hits the lecture circuit, so you can find several talks and interviews featuring Kobert on YouTube. She gets two thumbs up from me for making the complex and alarming phenomenon she reports easy to absorb and understand. Reading scientific articles on the subject gives information, true, but often the perspective is so specialized that the attempt to formulate a Big Picture from what you read fails either because you have too many gaps between the puzzle pieces or because the information is so technical you get sidetracked doing lateral research just to understand what’s going on. Books like Kolbert’s are a boon to people like me — people intensely interested in environmental reality but without a hard-core science background to get you into the Science Club. And it is a club, it seems, with all the rules and protocols (mostly tacit) you’d expect from a gentleman’s club in London. Kolbert’s job as intermediary between the Club and the Great Unwashed is crucial for getting information out in general circulation. The widest possible circulation is the only hope we have of motivating for change. The Science Club guys (it has very few gals, if the truth be told) don’t have the means to stop the mayhem, all they can do is try to figure out what’s going on and why. Doing something about it has to happen in some other quarter where people also usually lack a science background. Kudos to Kolbert for getting the word out in a way that makes good sense to everybody.

A couple months ago I wrote a post on the personal experience of living with the knowledge that we humans are messing up the biosphere, most likely already to the point of no return. It’s easy to set that knowledge aside in the course of daily life with all the things that that life requires — grocery shopping, cooking, cleaning, laundry and all the rest of it. Most people never rise above the level of daily life to engage the Big Picture of Planetary life. It’s never been the habit of human beings in general to do so, we’re creatures of the moment par excellence, always have been and it looks like we always will be. Due to some quirk in my consciousness I’ve always been a Big Picture person — my bad luck. Since entering the final phase of my life as a retiree I’m officially superfluous to the march of humanity with only the grave as my goal. Being in this state makes the Big Picture even more important to me as I try to dovetail my individual Big Picture with the Big Picture of the Planet that has sustained me over the course of my lifetime. Hence my recent research on the SME. Hence my re-read of Kolbert’s fine book on the subject. Hence this post.

There’s now a large body of information on the SME, now also called the Anthropocene Extinction Event because we anthros are the ones being naughty. A particularly interesting set of information is available on the website of populationmatters.org (here). There’s a downloadable PDF brochure you can grab, as well. Why not tuck in inside your Christmas cards this year? 🙂 I could go on forever listing links to scientific and popular articles describing the SME, but you know how to Google as well as I do and your taste for scientific literature probably differs from mine, so I’ll leave you to it and allow you to chart your own path of discovery. I’ll just discuss some of the information gleaned from Kolbert’s book and then move on to the personal dimensions of the issue.

Kolbert’s information is especially alarming because of the rapidity of the phenomena she describes and the advanced state of degradation already apparent in some ecosystems. Ocean acidification and its effects grabbed my attention most acutely when I first read her book — I knew nothing about it earlier, to my infinite shame, although I doubt I’m alone in that lack. When one considers that coral reefs in most places throughout the world are already 50% kaputt, the eyebrows have nowhere to go but up. Experts in marine biology expect the coup de grâce for ocean corals to come before the year 2100. Time for a citation from Kolbert, from the chapter entitled “The Sea Around Us”:

Since the start of the industrial revolution, humans have burned through enough fossil fuels — coal, oil and natural gas — to add some 365 billion tons of carbon to the atmosphere. Deforestation has contributed another 180 billion tons. Each year, we throw up another nine billion tons or so, an amount that’s been increasing by as much as six percent annually. As a result of all this, the concentration of carbon dioxide in the air today — a little over four hundred parts per million — is higher than at any other point in the last eight hundred thousand years. Quite probably it is higher than at any point in the last several million years. If current trends continue, CO2 concentrations will top five hundred parts per million, roughly double the levels they were in preindustrial days, by 2050. It is expected that such an increase will produce an eventual average global temperature rise of between three and a half and seven degrees Fahrenheit, and this will, in turn, trigger a variety of world-altering events, including the disappearance of most remaining glaciers, the inundation of low-lying islands and coastal cities, and the melting of the Arctic ice cap. But this is only half the story.

Ocean covers seventy percent of the earth’s surface, and everywhere that water and air come into contact there’s an exchange. Gases from the atmosphere get absorbed by the ocean and gasses dissolved in the ocean are released into the atmosphere. When the two are in equilibrium, roughly the same quantities are being dissolved as are being released. Change the atmosphere’s composition, as we have done, and the exchange becomes lopsided: more carbon dioxide enters the water than comes back out. In this way, humans are constantly adding CO2 to the seas, much as the vents do, but from above rather than below and on a global scale. This year alone the oceans will absorb two and a half billion tons of carbon, and next year it is expected they will absorb another two and a half billion tons. Every day, every American in effect pumps seven pouns of carbon into the sea.

Thanks to all this extra CO2, the pH of the ocean’s surface waters has already dropped from an average of around 8.2 to an average of around 8.1. Like the Richter scale, the pH scale is logarithmic, so even such a small numerical difference represents a very large real-world change. A decline of .1 means that the oceans are now thirty percent more acidic than they were in 1800. Assuming that humans continue to burn fossil fuels, the oceans will continue to absorb carbon dioxide and will become increasingly acidified. Under what’s known as a “business as usual” emissions scenario, surface ocean pH will fall to 8.0 by the middle of this century, and it will drop to 7.8 by the century’s end. At that point, the oceans will be 150 percent more acidic than they were at the start of the industrial revolution.

This process isn’t something we think about as we go about our daily lives, although the process of daily life is what causes the problem in the first place. That means my daily life and yours too, toots, let’s be crystal clear on that point. Just by living our daily lives we deposit carbon into the oceans every day. If you live in the United States it’s calculated to be about seven pounds a day. Seven times 365 equals 2,555 pounds, which is a bit more than 1.25 tons. The population of the United States is currently 325.7 million. Annually, then, Americans pump just under half a billion tons of carbon into the Planet’s oceans. The United States is only one country in the world — granted, we’re hard-core consumoholics, but even so, we’re only just one drop in the global bucket.

The facts are clear and to my mind, at least, incontrovertible. The excess carbon dioxide is indeed being produced by human beings, it is indeed entering the atmosphere, and once in the atmosphere it will inevitably be absorbed by the oceans with the result of a change in pH level. Observations made near Ischia in Italy at the site of a volcanic vent emitting pure CO2 into the ocean show that when the water reaches a pH of 7.8, marine organisms that produce their exoskeletons through calcification become unable to perform that process. It becomes chemically impossible for their physiology to produce calcium carbonate. So they disappear, i.e. become extinct. Pay close attention to the timeframe mentioned: the pH level that will effectively make calcifying organisms unable to survive anywhere in the world’s oceans is only 7.8, which will likely occur before the year 2100. Calcifying organisms are a big group, including molluscs, foraminifera, coccolithophores, crustaceans, echinoderms and corals. The molluscs include oysters and clams, so you can kiss your chowder days goodbye in the not-too-distant future. I never liked oysters, anyway, so I’m not bothered about them LOL.

That all of this mayhem will come to pass before the year of our Lord 2100 leaves my hair standing on end. Mind you, I’ll be dead long before 2100. I’m not sitting here in agonies about my descendants — I don’t have any kids so there are no grandkids, the biological buck stops with me. If I did have progeny my hair would likely start falling out after standing on end. What kind of world will people now in their infancy face when they become my age? One shudders to think. The complacency we continue to show in our daily lives, submerged in our quotidian Business As Usual as we are, is guaranteed to bring the environmental house down around our ears. It’s actually more like fiddling while Rome burns, to draw on another analogy perhaps more appropriate to the urgency of the situation. For people now in their 20’s who make the (IMHO) ill-advised decision to reproduce, it’s conceivable that their grandkids may know the oceans only as watery dead space, not the magical environment teeming with life we oldies have known throughout our lives.

How do you stop what Kolbert calls a “business as usual” emissions scenario by the year 2100? Let’s do the math: that’s 82 years from now. We have in fact far less time than that to stop pumping billions of tons of carbon into the atmosphere, things are starting to go seriously off the rails already. Is there any effective agency at work to bring about the rapid change necessary to put the kibosh to that reality?

The phrase that should be on our lips is “Paris Accord.” Oh dear. From February of this year we have an article by Brady Dennis and Chris Mooney in The Washington Post with news that’s less than joyful. The title is: “Countries made only modest climate-change promises in Paris. They’re falling short anyway.” (full article here). The upshot is grim:

Global emissions of carbon dioxide are rising again after several years of remaining flat. The United States, under President Trump, is planning to withdraw from the Paris Accord and is expected to see emissions increase by 1.8 percent this year, after a three-year string of declines. Other countries, too, are showing signs they might fail to live up to the pledges they made in Paris …

The reasons vary. Brazil has struggled to rein in deforestation, which fuels greenhouse gas emissions. In Turkey, Indonesia and other countries with growing economies, new coal plants are being planned to meet the demand for electricity. In the United States, the federal government has scaled back its support for clean energy and ramped up support for fossil fuels.

There’s still time for the world to set itself on a more sustainable track; many countries have until 2030 to meet their initial targets. But when policymakers from around the world gather at a key U.N. climate meeting in Poland later this year, countries will be forced to reckon with the difference between how much they say they want to limit the warming of the planet and how little they actually are doing to make that happen.

I may be accused of cynicism, but I never expected that the signatories would hold to the agreement terms. My momma didn’t raise no dummies and I have two good eyes, thank you very much. The momentum of our carbon-based civilization stemming from the way we live our lives is a juggernaut. It would take well beyond 2100 to shift entirely over to a different energy basis. And as the article points out, the President of the United States plans to ditch the entire enterprise. Hmm, wonder what the upshot of all that might be …

Just kidding — it’s perfectly clear what the upshot will be: dead oceans. You know, I know that the world’s nations are not going to curb carbon emissions in any major way before 2050, that evidence is clear beyond any question of doubt both from the track record and from a look at daily life as we live it. People have to get around and the internal combustion engine is still all we have to accomplish that job. After reading some of Kolbert’s book yesterday I needed to go the supermarket on my motorbike. I sat stuck behind a jeepney belching huge clouds of black diesel smoke until I found an opening in the next lane and got out from behind it. Jeepneys in the Philippines aren’t going to be replaced magically by some smokeless, low-carbon footprint vehicle. This is a developing country, nobody gives a rip if the jeepneys emit clouds of black smoke, 90% of them do it and the passengers just want to get from Point A to Point B as cheaply as possible. The reality of Americans in their Buicks on their freeways is just a variation on the same theme. The track record of the Paris Accord shows that a change in technology to eliminate carbon emissions exceeds the grasp even of those countries committed to its achievement. The result: the oceans (among other things) are toast. Kiss those coral reefs goodbye, kids.

What about land species? Well, there’s an interesting Wikipedia page (here) on species rendered extinct by human agency. The list only contains 109 species, so that’s far from the whole story. At the website of Mother Nature Network there’s an article about SME (here) entitled “6 things to know about Earth’s 6th mass extinction.” The evidence of species loss shows extinction happening now at a rate over 100 times what has been calculated to be an average background rate. Since about 99% of all the species that have ever existed on the Planet are now extinct, that may sound like no big deal. But it is a big deal because it’s happening so rapidly. Extinctions that occur in the normal course of evolution take thousands or millions of years to occur, unless of course they result from a catastrophic event like the impact of the nine-mile-wide asteroid that did in the dinosaurs. The rate of extinction events in our age is unnatural by the Planet’s own standard. And it’s becoming faster with the passage of time, not slower. Here’s another fact: we really have no idea how many species currently exist on the Planet. Without that critical piece of information there’s no way we can accurately gauge extinction rates. We are indeed the charging bull but not in a china shop, we’re in a huge china factory. We’re one rampaging species among millions going circumspectly about their own business. It’s already looking at this stage like the madness in Pamplona. Not good.

Faster means more discernible by human beings, since the timescale of our biology is ridiculously short by comparison with the Planet’s. When things operated entirely under the Planet’s management, the timescale of extinction events was so long that no discernible trace of it could have been visible to humans — excluding, as I mentioned, external catastrophes like the Chicxulub asteroid plowing into the Planet and doing in 75% of extant species (dinosaurs included) at the end of the Cretaceous period. As one scientist put it, if you were a triceratops in Alberta you had about two minutes after impact before you were vaporized. That qualifies as discernible in my book. But the processes in the other four mass extinctions were not so sudden. The mother of all mass extinctions, the Permian Great Dying that occurred 252 million years ago and eliminated an estimated 96% of extant species, was a much more drawn-out affair. We humans are currently precipitating the fastest non-impact extinction event in the Planet’s history. You’d think the evidence that we’re cooking our own goose in the process would slow us down a bit, but no, Business As Usual rules the day and on we merrily go along our carbon-emitting paths. There’s no stopping us, our momentum as a global collective is too great. Fossil fuels still run the world and will continue to do so until the general degradation of the biosphere puts a stop to us. The hand of restraint will not be human, that’s already become quite clear.

As I’ve gone through Kolbert’s book this time there’s a major difference. When I read it now, I have coming to mind scenes from the movie “Soylent Green.” From the Wikipedia page on the film (here) comes this information:

Soylent Green is a 1973 American post-apocalyptic science fiction thriller film directed by Richard Fleischer and starring Charlton Heston and Leigh Taylor-Young. Edward G. Robinson appears in his final film. Loosely based on the 1966 science fiction novel Make Room! Make Room! by Harry Harrison, it combines both police procedural and science fiction genres; the investigation into the murder of a wealthy businessman and a dystopian future of dying oceans and year-round humidity due to the greenhouse effect, resulting in suffering from pollution, poverty, overpopulation, euthanasia and depleted resources.

The scene from the film that comes forcefully to my mind is when the character Sol, played by Edward G. Robinson, decides he’s had enough of dystopian living and goes to the euthanization facility (video clip here). After he drinks the concoction that will dispatch him, he relaxes and is treated to a succession of images from nature — flowers, animals, beautiful landscapes. He dies contented remembering the world that disappeared as a result of human destruction of the biosphere.

Quite germane to our topic, don’t you find? No wonder that scene pops into my mind when I read that the seas will become acid sinks within the next 82 years and by 2100 the global population is projected to be 11.2 billion — there’s an excellent article on that projection here. No wonder I look at my own position in life — unlikely to last more than another 20 years — and realize that the shortness of my remaining term is a blessing. I’ll be dead before the worst comes. I won’t have to see the physical destruction of the Planet I’ve loved so dearly throughout my lifetime. I won’t need to see images of flowers and beautiful landscapes on a screen when I’m on my deathbed, my consciousness is already filled with them from a lifetime of engaging such loveliness in my own experience.

Another book I’ve been re-reading in the past few days is When Life Nearly Died by Michael J. Benton. It’s about the Permian mass extinction, the most severe of the mass extinctions in the fossil record. Reading Kolbert’s book at the same time as I’ve been going back over Benton’s brings a new perspective to me concerning the SME we’re busy precipitating. The causes of the Permian Great Dying are still in that fuzzy area science inhabits when it works off sketchy data and hypothesizes right and left to fill in the gaps. For the general reader like me this leads to the awareness that we really don’t know very much about a lot of things despite Science, which we moderns take as our Delphic oracle. You may well be Distinguished Professor of This or That but at the end of the day you’re dependent on the fossil record, which doesn’t give you much of the Big Picture that far in the past. So you end up cobbling together what little evidence there is with the glue of hypotheses. The result: what you spout sounds good but isn’t really all that solid with regard to facts. And we of the Great Unwashed want facts, of course — hypothesis holds little interest for us because we’re not academics who need to come up with something in order to keep pumping out publications in order to keep a job. Just the facts, ma’am, that’s all we plebes are after.

The geological evidence of the Permian-Triassic extinction is, however, ample enough to make certain that something very drastic happened resulting in massive loss of species across the boards. Estimates of die-off range from 76% to a whopping 96% of extant species. When we consider that level of extinction in comparison to the SME, it seems unlikely that we humans will manage to bring about an equivalent level of destruction. We’ll certainly mess things up royally, we’ve already managed to do that, but our reach does not yet extend to the ability to kill off 96% of all species on the Planet, unless something new and even more deadly than carbon enters our repertoire of chemical meddling agents. We’re not the hardiest or most adaptable species on the Planet by a long shot, so it seems to me that we’ll do ourselves in well before we manage to kill off 96% of living species. Now there’s a happy thought. 🙂

Back to the oceans and Kolbert’s information. It seems certain now that the scleractinian corals that build the ocean reefs we see in our cable TV programs will be toast long before the year 2100. They’re not the first reef builders in history, however. Before the Permian mass extinction rugose and tabulate corals did the work of reef building, and from the evidence in the fossil record they did a bang-up job of it. Apparently the Planet finds it appealing to have reefs in oceans– they’re a great place for a party, an aquatic equivalent of the bar in “Star Wars,” so why not? That particular lifeform keeps emerging throughout the evolutionary trajectory on the Planet. The scleractinian corals took over the job when the rugose and tabulate corals bit the dust in the Permian Great Dying — before that point they’d been a decidedly minority presence. Nothing daunted, they took up the task with enthusiasm and we see the results in things like the Great Barrier Reef (which is about 50% dead already, by the way) and those lovely island reefs and atolls in the South Pacific that seem to us Paradise itself, where we would gladly idle away our existence for a while if only we had the time and the money.

When push comes to shove, then, it’s unlikely that we’ll toast Planetary life to the degree that it can’t restart itself as it did after the Permain Great Dying. If Planetary life can recover from that massive depletion to achieve the extraordinary diversity we witness today, then the future of life with a capital L seems secure despite our depredations. Life will bounce back from the blows we deal it in some way or other after we finally manage to kill ourselves off in the process of doing in many of our companion species.

As I said, I’ll be dead before the worst of that process happens. When it finally does come it won’t be a pretty picture and I’m glad I’ll be gone. I’d only like to have a peek at the final act to see the dénoûment, because I think that would be very satisfying. That wish may sound grim, but if one considers the matter it makes perfect sense. Human beings have so long considered themselves the measure of all things that it would be good to see Planetary facts set our ideological misconceptions straight. We are most decidedly not the measure of all things. We are one species among millions of other species. We’re not permanent any more than any other species is permanent — let us recall that 99% of the species that have existed on the Planet are now extinct. What makes us think we’re exempt from those statistical odds? A bit too much self-importance, that’s what. The Planet will show that fault up for what it is with the passage of enough time, no doubt.

It’s galling to think of all the loveliness from this particular round of evolution on the Planet going to the dogs for the likes of what we humans have produced. Our stellar exemplars are so few and far between. For every Chartres Cathedral there are miles upon miles of squalid shacks along dirt roads in other parts of the world. For every e=MC2 there are countless lives lived in ignorance, poverty and squalor. The Planet is never any of those disagreeable things we are — ignorant, squalid, poor. It has a temper you don’t want to mess with, granted — especially where two tectonic plates meet — and it inhabits an extravagantly accident-prone universe where asteroids nine miles wide packing the destructive force of 10 billion Hiroshima bombs can appear out of the blue and seriously disrupt your evolutionary trajectory. But life always bounces back and whatever shows up in the next go-round is always a class act.

At the end of her book Kolbert says this:

Wouldn’t it be better, practically and ethically, to focus on what can be done and is being done to save species, rather than to speculate gloomily about a future in which the biosphere is reduced to little plastic vials? The director of a conservation group in Alaska once put it to me this way: “People have to have hope. I have to have hope. It’s what keeps up going.” …

I couldn’t disagree more. We shouldn’t have hope if the facts make it meaningless. I have no trouble living without hope if it fits the reality of the situation. If humanity in general were better at facing facts rather than grasping after ideological straws, maybe we wouldn’t have precipitated what is currently underway — a mass extinction event. The facts are the only thing that matters. Hope is useless both as a guide and as a corrective.

But here’s something hopeful: all evidence indicates that human beings are an evolutionary dead-end. We don’t have the intelligence or skill to prevent our own undoing. What happens to a species like that? Well, duuuh, it goes extinct. The results of the experiment of Homo sapiens sapiens — never was a scientific name more pregnant with irony or more arrogantly assigned — show incontrovertibly that self-aware consciousness is a bad idea, a very bad idea, unless the creatures who have it are able to make consciousness ascendant over their own biology. Evidence of the fact that we’ve never achieved that state is all around us in the animal lives being led all over the Planet by members of the Homo genus — the mindless reproduction, the wanton destruction of habitat for human use and all the rest of the sorry business we precipitate in the modern world. Our consciousness is so narrow and so instrumental in a mammalian way that it can’t even reach the level of encompassing the reality of collective humanity, to say nothing of the position of humanity as one species on a world with millions of species. We can’t even figure out how to play nicely with each other, let alone how to play nicely with our companion species. So what use is this big brain of ours, anyway?

What place, I ask you, does hope have in that scenario? There’s only one hope: a deus ex machina. And machinas are in very short supply these days, toots. In about 30 years they’ll be impossible to lay hands on at all — permanently out of stock. It’s been donkey’s years since I saw a proper deus come out of a machina anyway, so the best course of action seems to prepare oneself to kiss it all goodbye.

I just took a break for a couple hours and went out for a ride on my motorbike. It’s hard work getting 7 pounds a day of carbon into the oceans by riding a 150cc motorbike for a couple hours, so I’ll have to run the AC on high all afternoon and figure out something else to make sure I get in my carbon quota as the environmentally profligate American I am. If only I had a full-sized pickup with a big V-8, life would be so much easier … Anyhoo, it’s a lovely day here on Panay Island and the sunshine on the landscape did me good. There’s a country road going between two towns north of the city that I travel fairly often because it has great views over the countryside and to the mountains in the distance. The nearby landscape is predominantly rice fields. They stand in several different states at this point in the year — some already harvested and down to the dirt once again, some with the plants showing full heads of grain bent over and swaying in the breeze, some recently replanted and showing what looks like the fuzz on a baby’s head, only it’s bright green — neon green, in fact. I’ve never seen so intense a color in any plant where I come from. I enjoyed the views especially because I’ve been cooped up in the apartment the past few days with a visitor who isn’t very pitched on going out on the motorbike. I’ve found out that Filipino backsides have way less stamina than my own aging derriere. I can easily go on a three hour drive and be fine with a couple stops to air the backside. After half an hour the Filipinos I’ve had as passengers are already pissing and moaning about it being “too far.” Jeez mekness, kids these days LOL.

There is of course human habitation all along the way, that’s unavoidable. Would that it were otherwise … The road along most of its length is lined with bamboo huts, the dwelling of choice among the rural poor here in the Philippines. There are lots of stray dogs (at least they seem strays to me, they may be house pets on starvation rations for all I know), there are people ambling back and forth across the road apparently unconcerned with gauging how quick their gait needs to be to get them out of the way of traffic, and no doubt to these people all seems right with the world. It’s all they know, it’s what their lives are. Business As Usual.

Are these people concerned about ocean acidification? Do any of them have a notion that we as a species are precipitating a mass extinction event that threatens the survival of our own species as well? Of course not. Don’t be silly. They’re thinking about what to make for dinner, or about the family emergency that erupted a few days ago that nobody has any money to handle, or the wedding they need to go to next week or some such thing. Ocean acidification and mass extinction have no place in the proceedings. In effect, they do not exist in those daily lives. They do, however, exist for the Planet on which we live.

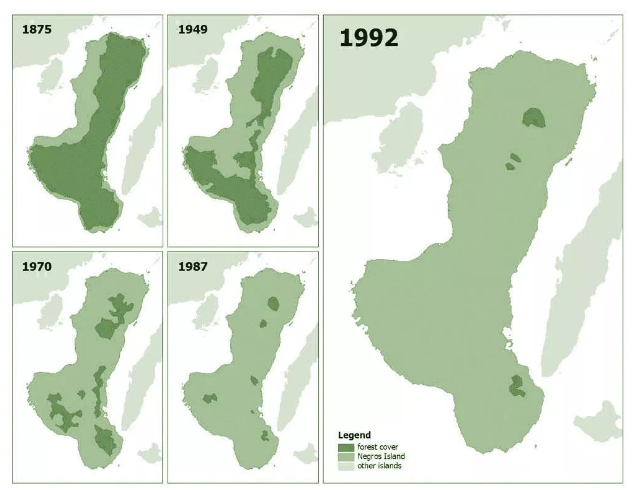

A look at human depredation to land-based environments is worthwhile, as well, if oceanography seems too arcane. Let’s use Negros Island (two islands away to the East) as an example so I don’t step on any local toes. From the website experiencenegros.com comes this handy set of maps showing the loss of forest cover on the island over time:

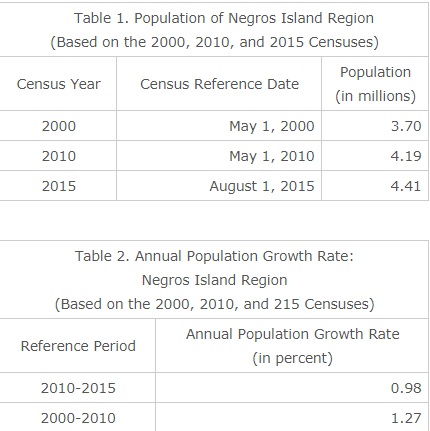

Here’s the census data on population increase (webpage here):

What place, I ask you, does hope have in this scenario? Clearly, we’re back at the deus ex machina thingey as our only recourse. And we all know how far that gets you …

As I said, I’ll miss the worst bits of how this nasty business plays out because I’ll be dead before it happens. I doubt I’ll extend much beyond 2030 — the year in which the signatories of the Paris Accord are supposed to meet their initial targets LOL. They may fail to meet their initial targets, but I won’t fail to meet my final one, you can rest assured on that account.

I dismiss Kolbert’s admonishments about hope. I think it’s necessary to learn to live with despair at this stage of the game. Despair is the only thing that will keep our vision clear enough to see the truth of the situation. Hope will only feed our rationalizations, our complacency. There’s no hand on the steering wheel of collective humanity, as I’ve pointed out elsewhere. We careen this way and that into the future like a rhinoceros blundering through a forest, leaving a trail of devastation in our wake. To hold out hope when the human population of the Planet approaches 7.2 billion and is expected to reach 11.2 billion by 2100 is ludicrous, because population drives the SME. People will continue to have sprogs without any thought for the morrow, just like they do in droves here in the Philippines, and the result will be that many of our companion species will bite the Big One. So, eventually, will we ourselves.

It’s already time to kiss it goodbye. That knowledge makes me appreciate all the more intensely the loveliness and wonder of the biosphere as I know it now. I’m one of the lucky ones, alive at a time when the damage remains largely invisible to the human eye. Having it out of sight although not out of mind is the the kindest fate one can meet at this point. I pity people who live 100 years in the future. Things will start to get ugly even before that point. The depredations of Homo sapiens sapiens (LMAO again at that name) will carried on the fine tradition we started by our descendents — until there aren’t any more descendents.

From the Planetary perspective we can also kiss humanity goodbye. From an evolutionary standpoint that’s exactly as it should be. Dead-end species bite the dust, it’s that simple. I hope the next round of evolution produces something more successful in the way of a dominant species than the likes of us. Fingers crossed on that one, Bridget …