January 2020

Well, we finally made it to 2020. About damn time. I studiously avoided reading the many articles I came across going on about what a crap decade 2010-2019 was. I was there, I don’t need any reminders, thanks kids. My thoughts have been trained instead on how to made the decade just begun better than the last. New Year’s resolutions obviously won’t cut the mustard, what we need is strategy. We need a plan. So I’ve been cobbling together a strategy, a plan to make sure that the upcoming decade becomes among my best. After all, at my age it’s not a dress rehearsal and you only get so many more tries — who knows how many? That increases the pressure to get it right the first time. So here’s what I’ve come up with.

Well, we finally made it to 2020. About damn time. I studiously avoided reading the many articles I came across going on about what a crap decade 2010-2019 was. I was there, I don’t need any reminders, thanks kids. My thoughts have been trained instead on how to made the decade just begun better than the last. New Year’s resolutions obviously won’t cut the mustard, what we need is strategy. We need a plan. So I’ve been cobbling together a strategy, a plan to make sure that the upcoming decade becomes among my best. After all, at my age it’s not a dress rehearsal and you only get so many more tries — who knows how many? That increases the pressure to get it right the first time. So here’s what I’ve come up with.

I’ve decided that the bugbear against which I will mount a full frontal attack is banality. Obviously this applies only to the level of the individual, I stand powerless before the banality that washes over us every day from the collective sphere. As the individual I am I can do nothing strategic against that greater rot other than make sure it doesn’t creep into my own sphere of experience. With my attention whetted to perception of it, I see it all around me. Being at present in an environment where the elderly and people involved in family stuff are thick on the ground I’m perfectly positioned to take notes about what NOT to do. And oh boy have I been taking notes. Yes siree.

But in order not to ruffle any local feathers I’m taking as my anti-baseline a figure from an essay by Virginia Woolf. That sounds innocuous enough, don’t you think? In her collection of essays entitled The Common Reader, Second Series, first published in 1932 by the Hogarth Press, appears the piece “Two Parsons.” I read it with great amusement because Woolf’s tongue is wedged so firmly in her cheek it sticks out like a sore thumb. The essay is one of those witty, elegant bitch slaps Woolf deals out to specimens of humanity who absorb her attention against her will — for I’m certain even without Googling it that this piece is one she wrote in order to bring in some cash, as so often she did with review articles. Why else on God’s green earth should she busy herself with the likes of James Woodforde’s diaries? The only conceivable explanation of that state of affairs is: money. All well and good. We all do things we’d rather not do for the sake of money. Fortunately in this instance there’s gold to be sifted from the dross — or perhaps I might better say that Woolf has worked alchemy with her examination of a thoroughly unremarkable person’s daily scribbles and turned the examination into something of greater value. In any case, I am edified yet again thanks to Ms. Woolf’s interventions.

And who might this James Woodforde of the unremarkable diaries be? I had never heard of the man before and I suspect you haven’t either. Here he is:

He was born in Somerset in 1740 — so may well have pronounced “s” like “z.” He made it eventually to New College, Oxford — ostensibly a feather in his cap, but that depends on your valuation of such events. His diary began in 1759 with the entry “Made Scholar of New College,” so obviously the event was significant enough to Woodforde to launch a habit of journal writing that ended up lasting over 40 years.

Mind you, none of us would ever have heard of Woodforde had John Beresford not felt it necessary to edit and then publish for our delectation The Diary of a Country Parson, which appeared in five volumes between 1924 and 1931. Why Mr. Beresford felt the impulsion to render Woodforde’s diary notebooks into printed volumes remains opaque to my understanding. One strains to imagine any improvement in the state of the world resulting from that publication. It was nevertheless accomplished and forced upon Virginia Woolf’s attention, hence her review essay in The Common Reader II.

The few biographical details about Woodforde mentioned above may sound vaguely exciting — a young man being scholarly (however ineffectual the results) and fluttering about in odd robes through the quads of Oxbridge — but any pretense of excitement soon stopped, in 1776 to be precise, as we learn from Woodforde’s Wikipedia page (here):

Woodforde was ordained and graduated BA in 1763, became MA in 1767 and BD in 1775. He appears to have been a competent but uninspired student, and the portrait he provides of Oxford during his two periods of residence as scholar and fellow (1758–1763 and 1773–1776) only confirm Edward Gibbon’s famously damning opinion that it was a place where the dons’ “dull and deep potations excuse the brisk intemperance of youth” …

On his father’s death in 1771, James failed to succeed to his parishes, and likewise failed to win, or rather retain, the heart of Betsy White – “a mere Jilt”. He returned to Oxford where he became sub-warden of his college and a pro-proctor of the university. He was unsuccessful in his application to become headmaster of Bedford School, but in 1773, he was presented to the living of Weston Longville in Norfolk, one of the best in the gift of the college, being worth £400 a year. He took up residence at Weston in May 1776.

Despite the wrench of leaving family and friends, he quickly settled down to a comfortable bachelor existence. He thought Norwich “the fairest City in England by far”and always enjoyed a trip to the “sweet beach” at Yarmouth. He was soon joined by his niece Anna Maria (Nancy) as housekeeper and companion, who stayed with him until he died. She also was a diarist and correspondent.

Oh dear. This bodes ill. Just what exactly is “a comfortable bachelor existence,” one asks oneself? And what about the poor niece who for almost 30 years lived as an appendage to her uncle’s “comfortable bachelor existence”? Did Nancy settle into what one must necessarily call a “comfortable spinster existence” to achieve equity with her uncle’s masculine version of the article? On reading no more than the bare facts of that existence I discern already a sinking feeling in the pit of my stomach. Ms. Woolf turns that feeling into the despair of certainty.

The story of Woodforde’s wooing of Betsy White is indicative of what is to follow over the next 30-odd years. Woolf nails it down for us:

The Parson’s love affair, however, was nothing very tremendous. Once when he was a young man in Somerset he liked to walk over to Shepton and to visit a certain “sweet tempered” Betsy White who lived there. He had a great mind “to make a bold stroke” and ask her to marry him. He went so far, indeed, as to propose marriage “when opportunity served”, and Betsy was willing. But he delayed, time passed, four years passed indeed, and Betsy went to Devonshire, met a Mr. Webster, who had five hundred pounds a year, and married him. When James Woodforde met them in the turnpike road he could say little, “being shy”, but to his diary he remarked — and this no doubt was his private version of the affair ever after — “she has proved herself to me a mere jilt.”

But he was a young man then, and as time went on we cannot help suspecting that he was glad to consider the question of marriage shelved once and for all so that he might settle down with his niece Nancy at Weston Longueville, and give himself simply and solely, every day and all day, to the great business of living. Again, what else to call it we do not know.

Oh dear. This is even worse. Not only is he maddeningly dilatory, he’s ill-fitted to perceive the consequences of his own actions. Even more incontrovertible on the evidence presented is that he’s a crashing bore. What else to call it we do not know. Ms. Woolf continues to flesh out this picture of unmitigated blandness:

For James Woodforde was nothing in particular. Life had it all her way with him. He had no special gift; he had no oddity or infirmity. It is idle to pretend that he was a zealous priest. God in Heaven was much the same to him as King George on the throne — a kindly Monarch, that is to say, whose festivals one kept by preaching a sermon on Sunday much as one kept the Royal birthday by firing a blunderbuss and drinking a toast at dinner. … But there was no fanaticism, no enthusiasms, no lyric impulse about James Woodforde. … When we think of the Woodfordes, uncle and niece, we think of them as waiting with some impatience for their dinner. Gravely they watch the joint as it is set upon the table; swiftly they get their knives to work upon the succulent leg or loin; without much comment, unless a word is passed about the gravy or the stuffing, they go on eating. So they munch, day after day, year in, year out, until between them they must have devoured herds of sheep and oxen, flocks of poultry, an odd dozen or so of swans and cygnets, bushels of apples and plums, while the pastries and the jellies crumble and squash beneath their spoons in mountains, in pyramids, in pagodas … all cooked, often by the mistress herself, in the plainest English way, save when the dinner was at Weston Hall and Mrs. Custance surprised them with a London dainty — a pyramid of jelly, that is to say, with a “landscape appearing through it”. After dinner sometimes, Mrs. Custance, for whom James Woodforde had a chivalrous devotion, would play the “Sticcardo Pastorale”, and make “very soft music indeed”, or would get out her work-box and show them how neatly contrived it was, unless indeed she were giving birth to another child upstairs. These infants the Parson would baptize and very frequently he would bury them. They died almost as frequently as they were born.

And with that the picture is complete. Nothing else of any importance will happen for the next 30 years. Just. Shoot. Me.

So there we have a circumstantial definition of banality. It’s like a grey winter sky against which all the landscape appears muted, subdued, robbed of its native summer color. It goes on and forever on and whatever happens in the course of the days is called “life” because what else to call it we do not know. But is that really life as it should be? As it can be? Should one’s expectations for the course of the days never breach the boundaries of such an existence?

Even in the 18th century voices of opposition arose. The voice of niece Nancy herself enters brusquely into her uncle’s diary through rough comments made about the humdrum nature of her life. To the uncle such comments were doubtless an eddy on the placid flow of days that went on until his death. They were far more than eddies for niece Nancy, as Woolf points out:

… One day she complained to her uncle that life was very dull: she complained “of the dismal situation of my house, nothing to be seen, and little or no visiting or being visited, &c.”, and made him very uneasy. We could read Nancy a little lecture upon the folly of wanting that ‘et cetera’. Look what your ‘et cetera’ has brought to pass, we might say; half the countries of Europe are bankrupt; there is a red line of villas on every green hill-side; your Norfolk roads are black as tar; there is no end to ‘visiting or being visited’. But Nancy has an answer to make us, to the effect that our past is her present. You, she says, think it a great privilege to be born in the eighteenth century, because one called cowslips pagles and rode in a curricle instead of driving a car. But you are utterly wrong, you fanatical lovers of memoirs, she goes on. I can assure you, my life was often intolerably dull. I did not laugh at the things that make you laugh. It did not amuse me when my uncle dreamt of a hat or saw bubbles in the beer, and said that meant a death in the family; I thought so too. Betsy Davy mourned young Walker with all her heart in spite of dressing in sprigged paduasoy. There is a great deal of humbug talked of the eighteenth century. Your delight in old times and old diaries is half impure. You make up something that never had any existence. Our sober reality is only a dream to you — so Nancy grieves and complains, living through the eighteenth century day by day, hour by hour.

It’s remarkable how little the fabric of daily existence has changed since the 18th century, despite the material differences Woolf points out. When one is living a life one’s horizon of sight shrinks to fit one’s circumstances. In point of fact it continues to shrink of its own accord and to narrow that horizon of sight unless countermeasures are undertaken to maintain the amplitude of its ambit. All around me I see people who have the circumstantial equivalent of tunnel vision. James Woodforde serves as a very useful index for the phenomenon. Reduce him to his motivational kernel, replace the curricle with a minivan or a crew cab pickup, change the dinners at Weston Hall for away games in some godforsaken purlieu of rurality and the historical shift makes little difference in matters of any substance.

I know exactly whereof niece Nancy speaks. Aye, and there’s the rub.

For Nancy and I are birds of a feather. I take my cue from her rather than from Uncle James, that old fuddy-duddy. As I comb through my memories for evidence of the dangers on my doorstep it springs readily to awareness. I see my paternal grandparents mouldering away in their mobile home, the most exciting thing of the week a trip to the supermarket to purchase items on sale. I see the long years of death by cubicle I endured in order finally to reach the state of retired freedom I currently enjoy. Each one of those years fairly screams at me, “Do something!” I see people of my parents’ generation succumbing to inertia and ill health, “life” — since what else to call it they do not know — being reduced to a round of unsatisfying social interactions and trips to the doctor, the focus still firmly on family although family members hardly ever show up because they’re far too caught up in their own narrow ambits of circumstance and in spending an inordinate number of hours behind the wheel of the minivan or the crew cab pickup. And I observe myself observing all these things with furrowed brow as doubtless niece Nancy was wont to do in the Norfolk fens.

I must say, the human world has not made it easy to use the freedom I’ve had for the past four years since reaching retirement at long last. I’ve found myself circumscribed and thwarted at every turn in my attempts to alchemize the raw matter of my freedom into lived experience. Whether that state of affairs is particular to my own times or not I can’t say. The evidence points, however, to such pressure toward limitation being part and parcel of the way humans organize “life” — what else to call it they do not know. For my part I think such a course of days hardly deserves being called “life.” It is no more than brute existence. It passes unmemorably and ends with a death that is far more a relief than it is a fulfillment of potential realized. How dreary. How very dreary. One might ask oneself whether it was worth the bother of having lived at all.

All this reading and rumination has only strengthened my resolve to point my big guns straight at the main enemy: banality. I see that what is required of me is a revolution not only of perception but of behavior. I must be vigilant against not only the outside world but against myself, since apparently the rot lies within us whether we will or no. It seems that the habits native to the human brain and the diminishing capacity of aging flesh push one toward a horizon that grows ever nearer.

So, I now know my enemy. What battle strategy have I developed? Full frontal attack. Throwing all resources into the assault, including the kitchen sink. It’s the only way to deal with such an adversary. Niece Nancy would understand that necessity without need for any explanation. I dare say she might have found the prospect of engaging such a battle exciting, as I myself do.

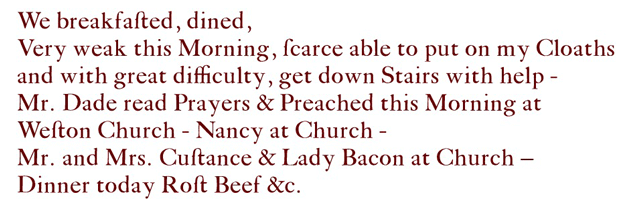

I regard my bellicose agenda as a rescue operation. I’m rescuing myself from that pallid, spindly thing called “life” because what else to call it we do not know. I want to establish sovereignty over the course of my days so that when at last I bite the Big One I will know in my bones that what has happened between now and that point of finality has come from my own agency, not from some cultural or biological default. My brain may trundle along in its mammalian habits and my flesh may indeed become weak, but my intent and the vigiliance that springs from it will remain strong, on that point I’m quite clear. I will do whatever it takes in order not to write as my last diary entry anything even remotely resembling that of James Woodforde:

In other words, I’ll be damned if I let the rot of banality take me and reduce my days to something only called “life” because what else to call it we do not know. Achievement of that goal may be difficult as the years mount up, but trust me, I’ll die trying.