August 2018

It escapes my understanding why human beings constantly create dichotomies in life, but there it is, the evidence stands plain before us. What’s a girl to do? Going through some old photos I hadn’t looked at in a long time brought forcefully to mind an issue I usually slap down every time it pops up like a jack-in-the-box from its relegation to the dank recesses of my mental real estate. I’ll go to my grave without having sorted it out, I expect. If I haven’t managed to accomplish that feat by this point in life, it’s unlikely to yield to my efforts before I bite the Big One.

It escapes my understanding why human beings constantly create dichotomies in life, but there it is, the evidence stands plain before us. What’s a girl to do? Going through some old photos I hadn’t looked at in a long time brought forcefully to mind an issue I usually slap down every time it pops up like a jack-in-the-box from its relegation to the dank recesses of my mental real estate. I’ll go to my grave without having sorted it out, I expect. If I haven’t managed to accomplish that feat by this point in life, it’s unlikely to yield to my efforts before I bite the Big One.

The issue is actually a dilemma. Even now as I think about it I can feel the wheels in my brain grinding slowly to a halt. It’s only a matter of time until the red light goes on and the system message DOES NOT COMPUTE flashes across the internal control monitor.

It all stems from the dichotomy between country life and city life. It’s an old trope, it goes all the way back to Aesop, for heaven’s sake, with his tale of the country mouse and the city mouse. Obviously the tension between the two modes of being is nothing new — which I find mildly comforting, although no help in arriving at a resolution. Perhaps there is no resolution. I hadn’t written the issue off as impossible before it popped up again a few days ago, but as I stare at its ugglesome horns ready to gore me yet again, I find I’m ready to chuck it into the bin and be done with it. So consider this post an act of mental housekeeping. Or, if you prefer a feline analogy, I’m finally spitting up that particular hairball and there’s an end of it. Enough is enough.

I began as a Country Bumpkin by definition, raised five miles outside a town of 1,500 inhabitants with the nearest neighbor six-tenths of a mile away — who happened to be my grandmother. I suppose that increases the bumpkin factor exponentially, since there could under more auspicious circumstances have been a retired world explorer down the road with tales of the African jungle to relate, which would have set thoughts of distant places rising in my mind like yeast raising dough. But no, it was Gramma, who I believe at that point had never been outside the State. No mental yeastings likely from that quarter, although cookies showed up fairly regularly in the proceedings, so it could have been worse.

Throughout my childhood going into town — especially in winter when the roads were a mess — was a Big Deal. When I go back to the area now I wonder what all the fuss was about. You can drive through the town in about two minutes flat and if you happen to be in the passenger seat with your eyes closed, you’ll have missed nothing that would make you a better person. If I were to write a post about the town itself, the title would run something like this: “Why Lake Wobegon Is A Load of Old Crap.” My attitude about the burg is one of the few things about me that hasn’t changed over the years. I’d rather perish than live there again, because I nearly perished when I did.

When I went off to college in the Big City the fact that I was a certifiable rube quickly came to the fore. The image to the right sums up the situation perfectly. No effing clue. I had no idea how to negotiate the urban environment, knew nothing about engaging an urban lifestyle, was entirely unpracticed in the ways of the city, all of which looked very grey (waaaay too much concrete in view, jeez, where are the TREES???) and all of which seemed to me rather scary. Yes, there were cool things like concerts and libraries and restaurants with food I’d only read about, but dealing with it all was an immense strain on my poor rural nervous system. After one semester I jumped ship and got the hell out. Thus began my impalement on the horns of The Dilemma.

When I went off to college in the Big City the fact that I was a certifiable rube quickly came to the fore. The image to the right sums up the situation perfectly. No effing clue. I had no idea how to negotiate the urban environment, knew nothing about engaging an urban lifestyle, was entirely unpracticed in the ways of the city, all of which looked very grey (waaaay too much concrete in view, jeez, where are the TREES???) and all of which seemed to me rather scary. Yes, there were cool things like concerts and libraries and restaurants with food I’d only read about, but dealing with it all was an immense strain on my poor rural nervous system. After one semester I jumped ship and got the hell out. Thus began my impalement on the horns of The Dilemma.

Images come to mind as I write … I see myself as a teenager sitting in my room after a day fixing fence in the back meadow, listening to Scarlatti sonatas from the electrifying recording done by Luciano Sgrizzi, played on a harpsichord the construction of which, of course, most closely resembles an armored car. That was long before the days of historical performance practice. In that rube environment Scarlatti was the odd man out. In the college environment fixing fence was the odd man out, it’s something only rubes do, for goodness sake. I see myself next in my college dorm room, fortunately not shared (not sure how I wangled that), reading Kafka for my Philosophy 101 class and feeling like Scotty had mistakenly beamed me to some dodgy academy in the Romulan Empire.

Fast forward a few years and I’m in graduate school, being smart as a whip on my full scholarship ooh la la, more than happy to spend hours talking about the ideological underpinnings of literary canon formation, but on the weekends going out sometimes for the entire day walking in the beautiful Virginia countryside. My thoughts then were on the hills and trees and wildflowers and on nothing else. For me it was the one point of sanity in the week when my body and mind felt put back together again after having been disjunct in parallel universes for days on end. I felt the sunshine on my face, the wind in my hair, smelled the earth and the plants and that fragrance particular to the South, musky and rich and complex. Lo and behold, it turned out that having a body was actually useful for something rather than just being an inconvenience in the pursuit of the life of the mind. The Country Bumpkin came into his own on those long walks. The budding intellectual was along for the ride but always remained under strict orders to keep his big mouth shut. During my years in Virginia I came to love that countryside dearly. It remains crystal clear in my memory. The particulars of the graduate program remain submerged and surface only on recall, which happens very rarely. That’s the best equivalent of protective amnesia I can manage. We all have our shortcomings …

I was always alone on those lengthy walks because all my co-conspirators in the graduate program were city kids. The idea of walking eight miles in a day on country roads would never have crossed their minds, not in a million years. One of my pals in the program came from New York City. Her mother had lived in Paris and was chums with Modigliani. (!) Another member of the team hailed from Lucerne and was wont to fly off at the weekend because the family was having an impromptu do in St Tropez. 🙁 Once during a gathering of my company-in-misery I recounted a few tales from my bumpkin past, things like fixing fence, splitting four cords of firewood to last through the winter, that sort of thing. All in a day’s work if you’re a rube. My friends burst out laughing and refused to believe a word of it. They knew me only as the person who speaks fluent French and German, knows a great deal about ornamentation in 18th century French keyboard music and makes rather a fine Viennese Windtorte. It was inconceivable to them that I came from a rube background. DOES NOT COMPUTE.

I was always alone on those lengthy walks because all my co-conspirators in the graduate program were city kids. The idea of walking eight miles in a day on country roads would never have crossed their minds, not in a million years. One of my pals in the program came from New York City. Her mother had lived in Paris and was chums with Modigliani. (!) Another member of the team hailed from Lucerne and was wont to fly off at the weekend because the family was having an impromptu do in St Tropez. 🙁 Once during a gathering of my company-in-misery I recounted a few tales from my bumpkin past, things like fixing fence, splitting four cords of firewood to last through the winter, that sort of thing. All in a day’s work if you’re a rube. My friends burst out laughing and refused to believe a word of it. They knew me only as the person who speaks fluent French and German, knows a great deal about ornamentation in 18th century French keyboard music and makes rather a fine Viennese Windtorte. It was inconceivable to them that I came from a rube background. DOES NOT COMPUTE.

When I went back home to the ranch to visit, an analog but inverse experience took place. I was once again The Rube. My family had no idea what I was studying and couldn’t be bothered to find out, such things have no place in the boondocks. The person my friends in the graduate program knew disappeared and back into the picture snapped the person that fit the backwater. I found myself montoring what I said, being careful not to use big words. I related next to nothing of my experience at university because it would have fallen on ears that had no means to hear. I began to feel as ghostly in that environment as I did at times in the intellectual hothouse of the university. It was clear beyond any shadow of doubt that both selves were real and perfectly valid on their own terms, but for some reason that I could never quite sort out they appeared to be mutually exclusive. That was the fly in the ointment.

When I went back home to the ranch to visit, an analog but inverse experience took place. I was once again The Rube. My family had no idea what I was studying and couldn’t be bothered to find out, such things have no place in the boondocks. The person my friends in the graduate program knew disappeared and back into the picture snapped the person that fit the backwater. I found myself montoring what I said, being careful not to use big words. I related next to nothing of my experience at university because it would have fallen on ears that had no means to hear. I began to feel as ghostly in that environment as I did at times in the intellectual hothouse of the university. It was clear beyond any shadow of doubt that both selves were real and perfectly valid on their own terms, but for some reason that I could never quite sort out they appeared to be mutually exclusive. That was the fly in the ointment.

I started my working life in big cities because that’s where the jobs were. If only I loved shopping, it would all have been so much easier … If only I loved crowds and noise and traffic, things could have been so much more memorable … The best I ever managed was an uneasy detente in which the bumpkin bided his time until I managed to get him out into the countryside. Internal relations between the Country Bumpkin and the City Slicker remained fraught largely because the City Slicker was an artificial superstructure on a bumpkin base. I wasn’t to that manor born after all, however much I appeared to have come from one of the posher suburbs of a major metropolitan area. I always had to watch myself in order to maintain the shtick. If I didn’t the bumpkin could come out with something untoward — a “howdy” perhaps, or a comment using vocabulary that would leave Her Majesty decidedly not amused, such as the pithy and expressive phrase “useless as tits on a boar hog.” Rube talk, that is …

About midway through my working life I’d had enough of the traffic and the concrete and the people, to be honest. City folk are only interesting in their own habitat, if the truth be told. They usually know very little about the wide world outside their urban bubble, and when they travel it’s usually to experience other urban bubbles. They’ve never experienced the feeling of a chinook wind in January (info here for the uninitiated, and on the European equivalent, the Föhn, here), an event that for me is highly charged with emotion. When you’ve been freezing your ass off for three months and all of a sudden a warm wind blows on your face from out of nowhere, it borders on a religious experience. Try explaining that to a City Slicker — eyes will glaze over in no time flat. There are no ears to hear it. I pulled off the City Slicker shtick to quite good effect, obviously — my colleagues in the graduate program would otherwise not have guffawed and disbelieved when I bared the truth of my rubeness. But maintaining the shtick was an effort and I gladly shed that persona when I was alone. Eventually the desire to shed it in daily life took hold and I began to search out jobs in smaller places. I moved to a city of about 100,000, then a few years later to a town of 35,000 and bought a house out in the countryside. BLISS! Going home to my acre of trees and plants was a delight of the first order. I swore never again to encase myself in the concrete jungle. I did spend the last five years of my working life back in the Big City, but outside the USA, so the circumstances were mitigated by the fact that the soil on which the concrete stood was very foreign, indeed.

Over the course of my adult lifetime I’ve tried to puzzle out this dichotomy but to no good effect. From the practical standpoint you have no choice but to take what you find on the ground. Human beings aggregate in a way that seems inevitably — for what reason I know not — to make their proximity disagreeable in proportion to their density. It needn’t be so, of course — nothing in Nature constrains us to that outcome. It’s the result of one thing: a complete lack of imagination. And of course we add into the mix the constraint of money, since that figures into absolutely everything humans do — yet another human creation masquerading as a Law of Nature. What a load of old crap.

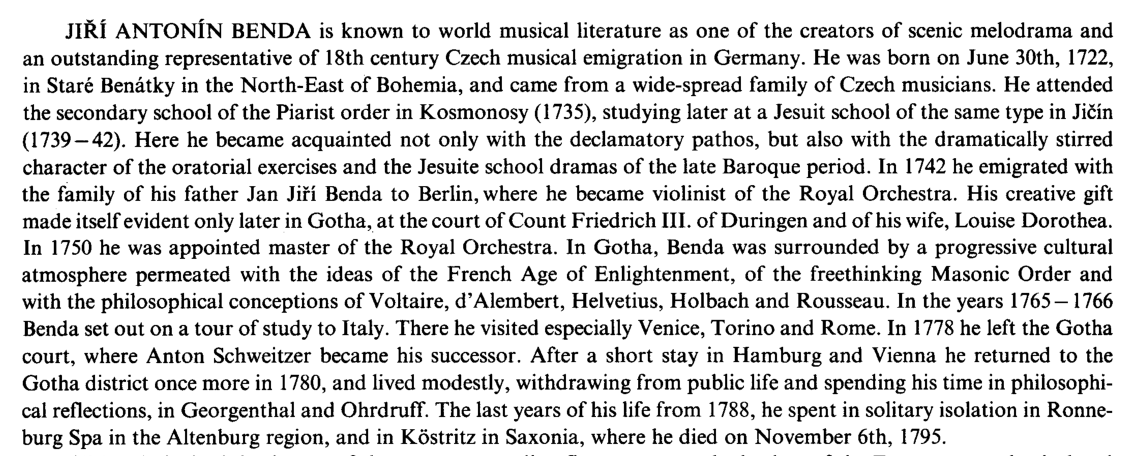

It’s time to call on the past to give us some pointers. I have in mind Jiří Antonín Benda (1722-1795, info here), a composer of Czech origin who went at the age of 19 as a violinist to the court of Frederick the Great. He did quite well for himself, becoming Kapellmeister at the court of Gotha, but during the last 17 years of his life he withdrew from the world of court affairs and ended his days in Bad Köstritz, which happens to be the birthplace of no less than Heinrich Schütz — which is surely one of the best arguments going for the notion that good things come from small packages. Here is interesting biographical information on Benda from the introduction by Jan Racek to a collection of 16 of Benda’s keyboard sonatas published by Supraphon in 1978 (Musica Antiqua Bohemica, 24):

Benda was not cutting and running, he left his position in his prime and at the pinnacle of his success. He was making a choice about how best to live his life. Did he go to Berlin to be in the middle of the musical life there, which was legendary? No, he did not. He ended up in the boondocks, interested in spending his time engaged in “philosophical reflections.” Curious. One wonders what kind of reflections on what kind of philosophy led him to sequester himself away in Bad Köstritz, which even today counts less than 4,000 inhabitants.

When I first read this information many years ago I was struck forcefully by Benda’s choice. It represents, I thought at the time, something resembling a secular version of setting the “normal” world aside to follow an inner calling or vocation. Of course, it could be the case that Benda was simply sick to death of court life with all its formal complexities and power politics. We have no journals or any other detailed biographical information about Benda that sheds light on the motivations for his choice. The fact that he made that choice and carried it through into execution for the rest of his lifetime was what struck me so forcefully. He was born in Benátky nad Jizerou in what is now the Czech Republic, a town that currently counts 7,000 inhabitants. Perhaps he, too, was at heart a country bumpkin and decided to turn his back on the city slickers at court to follow his own thoughts and live once again in companionship with the countryside as he must have done in his youth.

I know that impulse very well. I’ve acted on it twice in my adult lifetime, perhaps for a reason similar to Benda’s, who can say? My reason in each instance was the world weariness of the Country Bumpkin left to atrophy in the concrete nightmare for year after long year while the City Slicker carried on with the business of making a living as best he could. Benda’s defection from “civilized” life came to my attention some time after I myself had decided to defect, under circumstances that involved no ducal stipend or inherited wealth. That period of stepping aside lasted three years until fiscal pressure forced me back into the harness of the workplace for yet another round of Death By Cubicle.

The second defection happened some 12 years later and the awareness motivating that decision is sharp and clear in my memory. I was sick to death of dealing with people in the workplace, of people in general. The pettiness, the formulaic and predictable interactions, the meanness of spirit, the irrational attitudes and assumptions that came from God knows where, all came together to form a pill so bitter I could no longer swallow it. So I left my job, which was due to be on the chopping block because of institutional budget cuts anyway, and went back to the land on which I had grown up to sort out the gnarly business of living.

I’ve described some of the experience I had in the second of those defections in another post (here). The first was less intentional, less planned and a good deal more scary because my bank balance was not as robust as it was the second time round. The second experience also found me much nearer to running on an empty tank mentally, since I was approaching 50 and had been at the grind longer. It was with great relief that I became once again a Country Bumpkin, but this time a new breed of the animal, a hybrid if you will. Over the course of 20-odd years I had had ample opportunity to attempt to balance the City Slicker and the Country Bumpkin on the terms native to the city dweller. The best it ever got was excursions out into the countryside to appease the wailing of the bumpkin within. All I had done in the first defection was remove the City Slicker from his work environment without removing him from the city. The results were not particularly salutary, if the truth be told. The circumstances were fraught to begin with and the discombobulation of only part of the life context was a mistake. I should have undone the entire sorry business. The second time round I determined to do things with no holds barred. And that’s exactly what I did: I uprooted myself lock stock and barrel and headed quite literally for the hills.

The second experience lasted four years. It involved being off the grid and hence cut off from many things the City Slicker was used to having readily to hand, like Internet access. But being the dinosaur I am, I had grown up without a mobile phone in my hand or my attention glued to Instagram or Twitter all the day long, so doing without online access was not a dealbreaker by any means. One adapts, unless one knows nothing else (like a millennial) and would start foaming at the mouth if suddenly unable to check status updates from one’s cohort. There was a good public library two towns away — a stroke of luck — so as I had done when a young pup I read voraciously and studied things I wanted to learn such as botany, geology, history, quantum physics and whatever else took my fancy. Having the time and freedom to allow my mind to wander whither it willed was a delight of the first order.

The City Slicker was as sick of the workplace and the co-workers as was the Country Bumpkin scrunched up in the back seat all those years, so the adaptation was fairly easy. Mr. City Slicker did, however, raise objections on theoretical or — perhaps better said — hypothetical grounds. Isn’t that just what you’d expect from a city type, always griping about what is not rather than contenting himself with what is? But he had a point. After reading Thomas More’s Utopia once again (it had been years since the first time) he began to elaborate for himself an Ideal Village that would give the Country Bumpkin his due in addition to providing food for thought to the City Slicker sufficient in quantity and quality to stave off mental malnutrition. Why should that not be possible? Why in this day and age should that be at all difficult? Were not the means for the accomplishment of that end already to hand? So he thought and he thought and built up a picture of what a place that accommodates both the bumpkin and the slicker would look like.

The picture that emerged was decidedly futuristic, but by no means unfeasible given the state of modern technology. The City Slicker began daydreaming about it some 15 years ago, so the march of technology (notice that I eschew use of the word “progress” 🙂 ) has made even more things possible than were feasible at that point. The City Slicker wants access to the cultural and intellectual riches of the world from his country perch, you see. You can’t bring the Metropolitan Museum to the boondocks, that goes without saying, but in this day and age there’s no reason you couldn’t have a Cultural Center in a village with a beefy internet connection so that high-definition images of artworks could be had with the click of a mouse. The cafe in the Center could have Kindles to use while you sip your macchiato, crammed for next to no cost with the complete works of hundreds of authors. Public funding for the library component could include extra services for acquiring materials from other facilities. Lecture series could be organized using videoconferencing. In short, with the aid of technology it would be possible to create something that the City Slicker would feel made a passable equivalent of the kind of resource base available in a city. True, if you want to get up close and personal with a painting by Monet, you’re screwed, but do you really want to live in Chicago or New York City or Washington, D.C. to do that? If you attempted such lunacy you’d soon find the heels of the Country Bumpkin dug in so deep you couldn’t pull him loose with a Caterpillar D8. Just try it if you think I’m making up stories.

The picture that emerged was decidedly futuristic, but by no means unfeasible given the state of modern technology. The City Slicker began daydreaming about it some 15 years ago, so the march of technology (notice that I eschew use of the word “progress” 🙂 ) has made even more things possible than were feasible at that point. The City Slicker wants access to the cultural and intellectual riches of the world from his country perch, you see. You can’t bring the Metropolitan Museum to the boondocks, that goes without saying, but in this day and age there’s no reason you couldn’t have a Cultural Center in a village with a beefy internet connection so that high-definition images of artworks could be had with the click of a mouse. The cafe in the Center could have Kindles to use while you sip your macchiato, crammed for next to no cost with the complete works of hundreds of authors. Public funding for the library component could include extra services for acquiring materials from other facilities. Lecture series could be organized using videoconferencing. In short, with the aid of technology it would be possible to create something that the City Slicker would feel made a passable equivalent of the kind of resource base available in a city. True, if you want to get up close and personal with a painting by Monet, you’re screwed, but do you really want to live in Chicago or New York City or Washington, D.C. to do that? If you attempted such lunacy you’d soon find the heels of the Country Bumpkin dug in so deep you couldn’t pull him loose with a Caterpillar D8. Just try it if you think I’m making up stories.

So, with a bit of thinking outside the box and some organizational creativity it’s perfectly feasible to create something that would bring the cultural and intellectual resources usually associated with the city to the countryside, without any damage inflicted on the landscape. The Country Bumpkin would continue to have at close range those things that secure his well-being — Nature, activities out of doors, aesthetic engagement with the countryside and a sense of companionship with the part of the Planet that gives a home to his body as well as to his mind and soul.

The City Slicker deserves high praise for his efforts, no doubt about it, but he failed to take into account one primary factor: Lake Wobegon. It’s all very well to think hypothetically, but we live in a material world and people as a rule don’t strive continually for the ideal, do they. Of course they don’t, you don’t have to be genius to figure that out. Earlier I associated Lake Wobegon (in a regrettable lapse of ladylike behavior) with a load of old crap, and the reason for that association comes from people, not from the landscape. Do let’s be clear on that point. Crystal clear. The years I spent in what is supposed to be the idyll of an American small town are the very cause of the fact that I’d rather have a root canal following clumsily administered anesthetic than listen to “The Prairie Home Companion.” My experience of Small Town America doesn’t recall to mind Powdermilk Biscuits or Olaf and Sven yukking it up in the barber shop, it opens a floodgate of memories involving minds so small they threaten to collapse into singularities, a rigid but unspoken demand that everyone be exactly the same (Conformity From Hell is another way to put it), and a virulent, culturally reductive attitude that was mapped to a T in 1963 by Richard Hofstadter in Anti-Intellectualism in American Life (info here) and continues to this day very much alive and well particularly in the country’s Lake Wobegons. Been there, done that, got the T-shirt. I prefer my landscapes to be of the Oriental persuasion — open space, trees, flowers, a hermit-like scholar or two if you absolutely must have human figures, but not a bloody villager in sight. I make my own biscuits, thank you very much, and I don’t have a cat so I don’t need LuAnne Magendanz’s Kitty Boutique. Perish the thought.

That one oversight aside, however, our City Slicker deserves high praise for his imaginings, which in a different world with different people could be quite doable and bring excitement even to the Country Bumpkin, who over the years (talking just between us gals) developed a taste for early Baroque music and has been known to linger of an evening over a bit of Brie and a glass of wine. He certainly isn’t about to broadcast that information, knowing as he does what happens if you do such a thing in Lake Wobegon. He keeps his big mouth shut, oh yes he does. The City Slicker in his country setting has also learned to keep a lid on it, fortunately. No no, we really can’t be doing with this Lake Wobegon nonsense, we must go back to Benda for our cues.

Let’s imagine Benda in his country abode and see what he’s up to. In the 1770’s there’s no question of beefy internet connections, so we must imagine him surrounded by books. Perhaps there’s a library in his country house as one would find in a well-to-do townhouse in the city. There may be windows looking out over the garden, where certainly one is likely to find flowers. Beyond the garden wall one may glimpse another house in the village, or perhaps he’s contrived to position himself on the edge of town so he has a view out over the countryside with its lovely wooded hills and dales. We can imagine him getting up from his desk where he’s been writing, getting his hat and his walking staff and heading out the door to amble along the country lanes as he ponders what he read earlier that morning. It could well be that he’s been thinking about relations in the court at Gotha where he spent some thirty years, which led him to set for himself the task — and the pleasure — of re-reading Rousseau’s Du Contrat Social. He isn’t German but has lived so long in Germany that he now thinks in German. His own people, the Czechs, are under the political and cultural yoke of the Habsburgs and figure as no more than peasants in the scheme of the Imperial State. They have no literature of their own and their language — his native language — is the speech of the unlettered and oppressed. For that reason he chose to spend his years of withdrawal in Germany, not in the Czech lands. He walks in the sunshine enjoying the undulations of the hills and the intense green of the trees. He ponders as he walks, perhaps thinking about his experiences of the past, but perhaps as his time away from the bustle of the world has grown longer he lets the past be the past and stays with the present. He’s comfortable in his country setting and his life is filled with the things he engages with his mind. From being one of the region’s celebrated composers he has become simply a human being, content with the life he makes for himself and with the things that form the touchpoints in the daily progress of his days.

Were he in England he could be the perfect picture of the country gentleman. Were he wealthier he could easily be a member of the landed aristocracy. Were he living in the 21st century, he would simply be someone who took early retirement and is comfortable on his pension in an inexpensive place to live, quite happy doing his own thing.

Benda, too, is in Lake Wobegon, but in his case it’s called Bad Köstritz. He is solitary. He gets along well with his neighbors, one suspects, but hardly gives them a rundown of the reading he’s done for the week. Nor does he expect to find in Bad Köstritz anything resembling the literary circles and salons he knew during his years at the Gotha court, where ideas ran through the corridors with a speed almost equal to that of the gossip. Bad Köstritz is no ideal village, just as Lake Wobegon is anything but ideal.

I take my cue from Benda because I think he achieved an optimum given the circumstances we find on the ground. I aspire to be like him, carrying on with my own agenda and allowing the world to take its own course. It’s a pity I haven’t landed in Bad Köstritz, the pictures of the place are delightful. I’ll just do the best I can where I am, tending to both the Country Bumpkin and the City Slicker and leaving the devil to take the hindmost.