Wat Ched Yod is my favorite temple in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Chiang Mai fairly bristles with stunning temples, as anyone who has visited the city will know. There are so many you’d need months to see them all. Ched Yod is my favorite because it combines so many different environments and avenues of experience. There you can find history, beautiful architecture, lovely gardens, the full experience of Buddhist lay practice, and — perhaps most importantly — peace and quiet, which seems to me an integral component of a temple complex. During my stays in Chiang Mai over the past several years I’ve always gravitated to Ched Yod, to the point that sometimes for a good stretch of time I go to no other temples. It’s easy to spend the entire day there if you’re of a mind and to exercise not only your soul but your senses, as well. Temples like Ched Yod offer large spaces, multiple environments, different things going on in different places, and it’s all beautiful and welcoming enough to harbor your soul and your body for as long as you care to stay. There are other temples in Chiang Mai that offer as much or more architectural bang for your clock hour. Even if hard pressed I couldn’t possibly say which temple is my favorite on the basis of architectural and artistic merit alone — one finds oneself before a quintessential embarras de richesse. Choosing a favorite under those circumstances is not only difficult but foolhardy, into the bargain.

Ched Yod is a little world unto itself in the Chang Phueak area of town. Once you go past the entrance sign seen in the pic above, you can let the outside world go for a while and relax your awareness to rest on whatever you intend to experience within the complex. For it is a complex, not just a temple, with many different buildings, open-air devotional sites, a large garden, and beautifully designed and landscaped grounds. My purpose in this post is to highlight some of the beauties of each type of environment and to show what a stunning ensemble they make all together.

Before we jump in, however, it’s caveat time. My knowledge of Buddhist architecture is anything but encyclopedic, and while I have a handle on the layout of Thai Buddhist temple complexes, I make no claim to exhaustive knowledge, nor even to certain ability to name all the architectural components of such complexes off the tip of my tongue. I’ll do the best I can to be accurate. Even if I succeed in that endeavor, however, there’s still the matter of spelling for transliterated Thai terms. Chet or Ched or Jed? Yot or Yod? Since I don’t speak, read or write Thai, it’s all Greek to me. Curiously enough, information on the temple available online is least likely to use the spelling on the entrance sign. An odd state of affairs, you may think, but in the business of transliteration from non-Latin scripts all bets are off. I’ve opted for Ched Yod, which represents a compromise position between the two extremes — a voiceless alveopalatal affricate to get things rolling, but voiced terminal consonants, not unvoiced, since they’re softer on the ear and remove any risk of spraying your mango juice on passersby if you pronounce too vigorously. So with that out of the way, are we all good? Happy campers? Perfect, down to business, then.

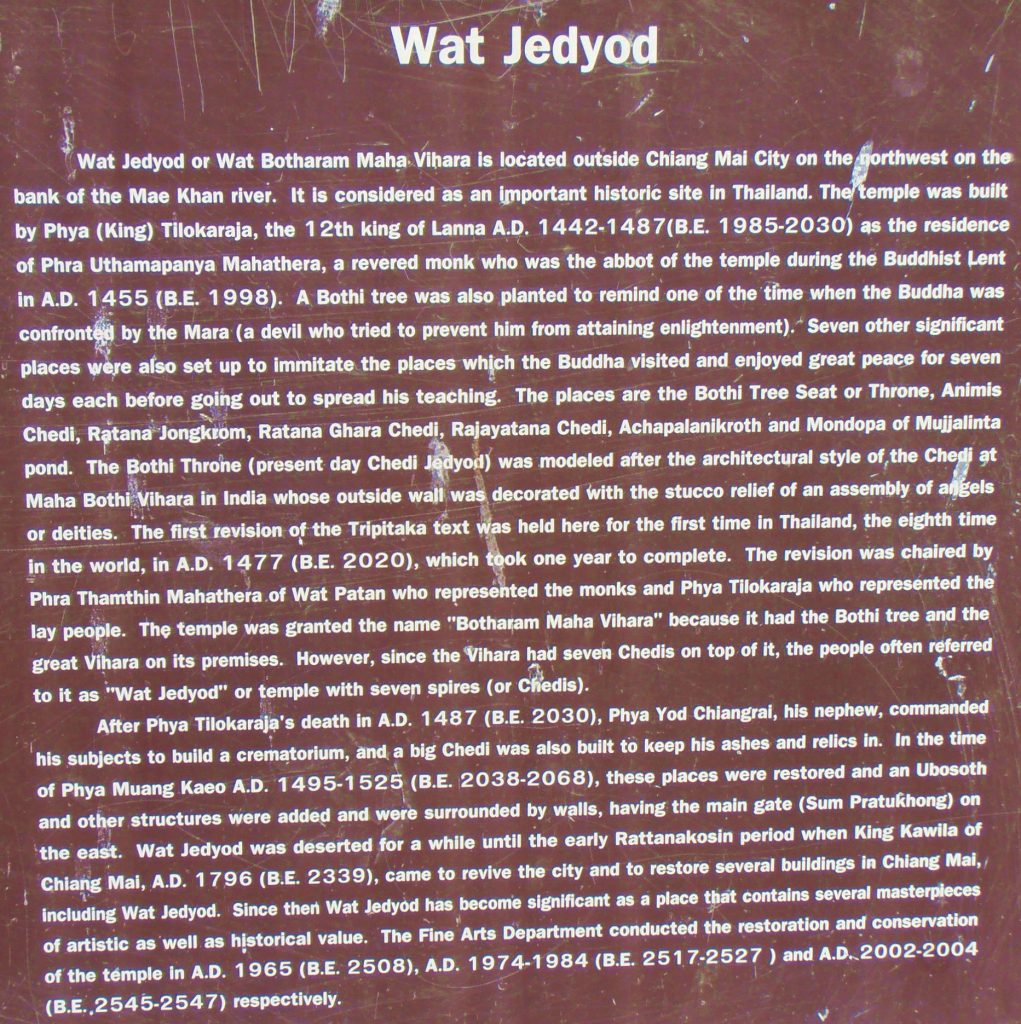

If I’ve made the image above on the right large enough for you to read comfortably (fingers crossed), then I needn’t bore you with the recital of the temple’s history, which you can also easily find online. From an architectural standpoint, however, its history deserves mention because the temple was built to accommodate the Eighth World Buddhist Conference held in 1477. That’s a good while ago. What was the Buddhist world like at that point in history, and how much on the map did Chiang Mai need to be to become the site where such a momentous meeting took place? While I’m gathering my historical data you can busy yourselves looking at some pics germane to the topic:

Thailand is a predominantly Buddhist country — unless you’re from down by the border with Malaysia, then that statement is patently false from a local perspective — but there are twists in the history of that Buddhist presence. In earlier parts of its history the country was largely Mahayana and under direct influence from India. After the decline of Buddhism in India and the ascendance of Sri Lanka as the seat of Buddhist clerical authority, the Sinhalese sent missionaries to the area of Myanmar and Thailand and converted many of the local rulers to their Theravada school of Buddhism. Among the converts was the man in the second picture, King Mengrai the Great, the founder of the Lanna kingdom and also the founder of Chiang Mai in 1294. It was a king in the line of Mengrai’s Lanna Kingdom who founded Wat Ched Yod.

The third picture brings us to the 1470’s. As we established, Ched Yod was founded to serve as the site of the Eighth Buddhist World Conference in 1477. Given the historical tenor of things, I suspect we’re talking about Theravada sanghas when the word “world” is used, and we should assume that Sinhalese Buddhists from Sri Lanka figured among the attendees. No record exists of what topics were discussed at the Conference, nor what decisions were ultimately made with regard to scriptural canon or doctrinal matters. The buildings created for that meeting are struggling to hold their own against the force of history. The third photo shows that the struggle remains valiant and still relatively successful: those are the towers of the Maha Chedi, as it’s called, which was modeled after the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, India, near the spot where it’s believed Buddha attained enlightenment. The Mahabodhi Temple is a product of the Gupta Empire and dates from the 6th century CE. It’s not difficult to see that the shape and arrangement of the spires of the Maha Chedi mirror the general arrangement and relative proportions of the Mahabodhi towers. But to be perfectly honest, it seems to me really no more than a doff of the hat in deference, because the Maha Chedi at Ched Yod is a very modest affair, if the plain truth be told. It makes its impact through the perfect proportions of its petite self and through the exquisite detail of its decoration. So rather than give you panoramic shots of the thing, I’ve zoomed in for two bits of detail that show why it’s such a delight to be near so the eye can take in things at close range. That intimacy would be impossible at Mahabodhi, which is colossal. For the historian, the conoisseur of historical architecture, the aficionado of stucco work in all its fineness and skill, the Maha Chedi is the better place to spend the day ambling about and getting up close to things.

The Maha Chedi was built during the apogee of the Lanna Kingdom. The Lanna legacy is visible to a much greater degree in the modern buildings of the complex like that in the last photo in the row. There will be more pics of architectural detail from the modern buildings, which are exquisite. Lanna style is known for its multiple (most often three) roofs nested like stack tables, each with its crown ornament of a garuda, the mythical creature used only on temples and royal buildings. The vibrant invention expressed in the ornamentation of Lanna-style temple buildings and the quality of craftsmanship that brings that invention to expression both leave one slackjawed. I’ve never seen such intricate architectural detail elsewhere with such coherence of symbology packed into so small an area. It accomplishes this dovetailing without ever becoming overwrought, in my opinion. The architectural detail of many European buildings (UNESCO forgive me but the capitals of St. Michael’s in Hildesheim come to mind 🙁 ) looks by comparison like chainsaw sculpture. You know about chainsaw sculpture, right? No? Well, if your aesthetic sensibilities are so frightfully refined and have been formed in so rarified an atmosphere, Google it, babes, and see how us little people live 🙂

You’re free to wander about as you like around the complex, there are no guards or watchkeepers milling about telling you to stay on the paths or not to touch this or that — I always have a sense of complete ease there, knowing that nobody will get up in my grill about infractions of some sort or other. Since it lies somewhat outside the central district of the city, the number of people on the grounds is usually low and they’re all locals, as far I can tell. Despite my being decidedly non-local (and noticeably pinkish) nobody turns with surprise to look as I come round a corner or sit in one of the shady places as people pass by. It’s a very peaceful place, offering the opportunity to set aside the chaos of the city and enter into its haven. And that’s exactly what we’re going to do. We have different tour streams available — artsy fartsy going on about architecture and art, a gardener’s delight tour, and one for the tourist who just wants a place to hang out for a while and let the world go by. So off we go.

ARCHITECTURE

There are seven historical stupas (chedis) in the complex in addition to the new buildings that form the working public spaces typical of all Thai temple complexes (an overview of Thai temple architecture is available here). We’re concerned here with the “Phuttawat,” the part of the complex devoted to Buddha, which contains the main buildings used for religious purposes. Let’s start with the historical structures and afterward have a look at the modern ones.

An aside: I apologize for the lackluster photos. The day I took them was uniformly overcast, so what’s a girl to do? I do have the perfect excuse, however: TOURIST. You pays your money and you takes your chances. The next day was off to the next place on the (overly large) to-do-list. They perform the job asked of them in this post well enough, however, so I won’t beat myself up. I’d only do that if I were discoursing on medieval Flagellants associated with European cathedrals 🙂

The first two photos in the top row are of the Maha Chedi, the stupa built in the 1470’s for the Buddhist conference. Since it takes its aesthetic impetus from Indian architecture and symbology, it’s unlike any other stupa I’ve seen in temples in Chiang Mai. The name of the temple comes from the seven spires of the Maha Chedi, since Jed Yod means “seven spires.” The Maha Chedi is precious particularly for its sculptural details, of which the first two pics give examples. There are 70 stucco relief figures like the one in the second pic, representing divas (thewada) of Indian Buddhist origin, but the story runs that the faces of the figures were modeled on relatives of the founding King, Tilokarat. Only their hairdresser knows for sure these days whether there’s any truth to the tale. The ashes of King Tilokarat repose in the largest of the historical stupas, so he chose to go into history within the temple complex he brought to realization. And a lovely place it is to spend eternity, so well done, King T.

The third pic in the top row is a Lanna-style historical stupa. It uses brick for the major structural portion of the building and stone for the architectural details. The Buddha figure in the narrow vaulted space struck me as dwarfed by the pile of masonry around and atop it. Nothing in such buildings is done just for fun, however, everything — I mean everything — means something, so the disproportion between statue and stupa was somebody’s intent to express something meaningful to Buddhists of the day. I can offer no insight into that meaning, however, and my search to find something has left my hands woefully empty. May someone wiser and more erudite than I fill them and cover the shame of their nakedness.

The last pic in the top row is quite familiar to anyone who has wandered at length around Chiang Mai, because one comes across such stupas wrapped in orange cloth fairly frequently, and in places one would least expect to find such a thing. The very first time I visited Chiang Mai there stood across the street from the entrance to my hotel a small brick stupa of the same type, or rather the remains of one, since only about 3 feet of crumbling brickwork remained above street level. It, too, was wrapped in orange cloth and had on its undulating ledges offerings of food and flowers. Religious life in the Buddhist lands escapes the boundaries of a single day or a single hour as is the wont in the Protestant Lands with their Sunday services. Buddhist religious life spreads out across the day and the week just as life itself does. Rather a sensible approach to things, I find.

The first pic of the bottom row is a study in contrasts. In the foreground are two of the historical stupas in Lanna style, which frame the Maha Chedi with its spires of Indian inspiration. The difference between the two architectural traditions is thus put to a point. Both traditions are lovely in their own way, of course, it’s not a question of making comparisons and taking sides. Everything counts, it’s all brilliant. Just as Nature doesn’t make all leaves to the same pattern, so should we vary the shape and form of our buildings. It’s the natural thing to do.

The next pic was done with a photographic purpose in mind, I will confess. It’s a study in old and new, a juxaposition of Haven and Chaos (apologies to modern Chiang Mai). It’s the South Gate of the temple complex, obviously in Lanna style from the period of original construction. Look beyond it and there you see modern Chiang Mai glaring at you, powerlines cutting your line of sight at every turn, multistorey buildings squashed up against each other for kilometers on end, the highway separating them from you as you lurk behind the security of the gate like some kid hiding behind his mom’s apron. As I said, the temple complex offers haven from the city. It’s peaceful, has beautiful architecture, beautiful gardens. You’ll find none of that within easy reach on the other side of the gate, so for heaven’s sake let’s turn around and head back in the other direction.

I’m a rank amateur photographer so don’t ask me how I managed to get the stupa in the next pic at an angle to ground level. I’ll take the easy way out and blame the camera — bloody stupid thing, so glad I got rid of it … This stupa is in classic Lanna style: bell-shaped, fitted with a needle spire, as classically Lanna as you please. If you look at the stonework around the lower drum you’ll notice that it features next to no decoration on its surface. When you consider the riot of ornament that covers Lanna-style temple buildings, it becomes clear that Lanna Thais were not very keen on carving in stone. That fact makes the Maha Chedi all the more remarkable and justifies its unique place in the temple repertoire of the city.

The last pic is of the spires of the Maha Chedi — from fairly close range, mind you. As I said earlier, it’s but a doff of the hat to the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, which is ENORMOUS. I was fully aware when I visited Ched Yod of its history, but I found the relationship to Mahabodhi informational, nothing more. The charm of the Maha Chedi works its own magic, there’s no need to compare it to anything else. Even had it been proven by subsequent scholarship that the design derived from a visit to Chiang Mai in the 1470’s by extraterrestrials from the Pleiadian constellation, I’d emit an “ah, really …” and just keep looking. The proportions are lovely, the shapes pleasing on their own account without any reference to anything else, and it’s beautifully quiet in the vicinity. Who needs anything more? And look at those trees! All that beautiful stonework and handsome trees to frame it … my knees are getting weak, let’s move on to the modern architecture, shall we?

Top row, first pic: the Vihara, or “wiharn” if you prefer the Thai word. This is the main space where monks and lay people meet for religious activities. There’s that luscious ornament covering the facade and pillars and the Lanna-style roof with its stacked elements as we saw above. The acacia trees are a big plus, in my opinion, and deserve equal billing. They’re old and their canopies spread out across the sky very handsomely. On some of my visits I was quite content to spend a long while in the shade where I took this photo just to admire the vihara in its setting of acacia finery. The European building that comes to my mind by way of simile is the Amalienburg in Munich, which is, of course, as secular as the day is long. I love that building to bits, but when sitting with my gaze on the vihara of Wat Ched Yod I become acutely aware of the depth of meaning Thai temple architecture communicates, even at a distance. The Amalienburg is a feast for the eyes, true, but the vihara at Wat Ched Yod and all its companion buildings engage the eyes in order to reach the soul. Therein lies the difference, in my experience. I feel lifted up by sitting with the vihara, which carries me to a point of spiritual attention through its very presence. How lovely.

The next pic is the Ubosot (more information here), small enough to warrant only two stacked roofs rather than three, and bounded by its stones as is the wont for an Ubosot. Here the contrast between the blank white space of the walls and the complex, intricate ornament of the windows brings the beauty of the latter to full effect. Garudas festoon each roof corner to show that serious business is transacted within, since the Ubosot is the holiest among the temple buildings, where monks are ordinated.

The contrast between the historical and modern buildings of Wat Ched Yod is one of its special appeals, I think. The third pic in the top row is another attempt by Yours Truly to capture that juxtaposition and its aesthetic impact. The view in the pic includes the Maha Chedi and the Vihara, which latter uses the contrast between blank white wall space and elaborate carved window frames. The alien (I mean Indian, not Pleiadian) aesthetic of the Maha Chedi stands out even more clearly by contrast with its neighbor, but again, the difference elicits inclusion, not mutual exclusion. Acacias extend the spread of their canopies over all like the cloak of the Virgin in Piero della Francesca’s “Misericordia” polyptych in Sansepolcro. Nature is always a feature of what one sees throughout the Wat. As I said: everything means something within the temple complex, including the acacias. And everything counts. Trees are people, too, you know.

The last pic of the top row is another Ubosot, this one with a double set of demarcating stones and carved gables that have put its name on the map, which should come as no surprise given their great beauty. The carved panels set into the open bays of the porch are equally stunning. This kind of building can easily eat up an entire morning or afternoon, perhaps even a whole day if you really give yourself over to appreciating all its wonders. You can zoom in, zoom out, focus on detail or on the harmonious balance of architectural elements, it matters not, the building will hold your attention and surprise you at every turn. I’m always mindful when I see such things that people did them, they didn’t just appear out of nowhere. But we know nothing about those people, those expert craftsmen who achieved this wonder of ornament and artistic excellence. I would pay homage to them individually if I could, they deserve every bit of credit that can be steered their way. So in their historical anonymity let me just say: Good on ya, boys, top drawer job of it, give yourselves a raise.

The bottom row of pics gives you samples of architectural detail, which you can survey as intensely as you please. I suggest that you keep an eye out for invention in design as well as for stories intended to remind you of something important or to teach you something you should remember. My problem in that regard is having sufficient background in Buddhist scripture and iconography to know what it is I’m supposed to pay attention to. I never fail to appreciate the design bits, but I fear some of the stories go over my head 🙁 But a girl can only do what a girl can do, so I’ll just soldier on.

A word about Nagas, the two figures in front of the second Ubosot with the fantastic gables. They’re protective deities used throughout the Buddhist lands as part of architectural design, but the ones in Thailand are elaborate and exhibit so much personality that I can only assume there must lurk some special affection on the part of Thais for these creatures. They deserve their own set of pics:

The images in the top row come from other temples in the area. The first one is from one of the major temples in the Old City (I forget which one, bad me). The second is from an astonishing wat out in the countryside between Chiang Mai and Doi Saket, which just goes to show that the city doesn’t have the monopoly on stunning architecture. The last two are from the main temple in Doi Saket, a town about 20km northeast of Chiang Mai. If I had to dub any temple in the area Naga Central, it would be that one. The number of multiple-headed nagas there exceeds anything I’ve seen anywhere else in the vicinity. The naga is actually the hooded cobra, rather a nasty piece of work if you’re on the ground stomping about in the jungle, as we all know. Abstracted into a protective deity, however, the nasty bit disappears and the artistic element takes over. The transformations that occur in that process can result in nagas like the ones at Wat Ched Yod, who are thoroughly domesticated. If you take away from them all their fancy ornament you end up with a creature who could pass with tolerable ease as a turtle at the pond in The Wind and the Willows. My impulse is to tickle them under the chin, not to coil back in horror. I quite realize they mean to be fierce, but we needn’t take everything so seriously, really, don’t you find? So for me they are avuncular turtles in fancy dress, no need to take a fright, it’s all just pretend and nobody’s going to get chomped. Just relax and enjoy the show.

The number of buildings in the temple complex far exceeds what I’ve shown here, so expect to be surprised at every turn as you go about the place. One is as lovely as the other into the bargain, so don’t rush, you’ll miss something wonderful if you do.

GARDENS AND LANDSCAPING

On we go, then, to the gardens and the landscaping. The gardener and the horticulturalist supplant the aficionado of history and architecture now, so do whatever you need to do in this game of musical chairs to position yourself appropriately, the tour bus is departing … Let’s start things off with some pics:

For all but the last photo in this group I really need say nothing by way of explanation. The gardens and the landscaping are superb, but that fact does nothing to set them apart from any number of other public venues in Chiang Mai. The Thais are apparently blessed by the Deity with an infallible sense, probably active from birth, that allows them to create noticeably accomplished landscape and ornamental plantings with the apparent ease of drawing breath. I’ve never seen the like of it anywhere else and when I go to Thailand I know I’ll spend long hours visually wallowing in the results, which are available at every turn of the head. Thailand gives itself out as the Land of Smiles. All very well and good, smiles are lovely and the more the better. But to my mind this natural penchant for coming up with perfectly structured, balanced and harmonized arrangements of plants is the truer hallmark of the country. The Land of the Magic Touch, that’s what I’d call it if I were put in charge of marketing.

The last pic of the bottom row shows that magic touch particularly well, I think. It’s a container planting on one of the walkways from the front of the complex toward the Maha Chedi, and there it sits, for no good reason other than the beautification of space and the pleasure of the eye, with what looks to be a dancing girl (rather than an iconic sacred figure) in a posture one cannot possibly imagine the Virgin Mary adopting in a church without scandalizing the Ladies Bible Study Group. But it’s all good, dancing girls with their bits wrapped in orange cloth (OMG is that a nipple I see poking out on the left mammary??) have their rightful place in the temple complex, as well, revealing that even the female figure and the dance can be included in what we call sacred. And just look at the plants, for heaven’s sake. LUSCIOUS. We have flowers, a lovely variety of foliage shapes and colors, all looking as if they just happened naturally to be where they are. But it didn’t just happen, somebody put that composition together. Some magic hand has given its touch to this group and the eye lingers on the beauty of it. This happens all over in Thailand — hotels, public parks, the outside seating areas of restaurants, absolutely everywhere. Including the grounds of temples. To my mind, it figures chief among those characteristics that make Thailand Thai. I never get enough of it when I’m there, the eye cannot sate itself on such loveliness even during a long stay. There’s always some new handsomeness around the next corner.

BUDDHA FIGURES

Since we’re at a temple complex, it’s not surprising that the figure of Buddha figures largely in the scheme of things. Duuh. But the quantity and variety of images over the grounds of the complex is a distinct and special feature, so let’s have a look at some of them.

These images represent only a portion of the Buddha figures in the complex, mind you. Each of them had a special impact on me, which is why I chose the photo for inclusion. The first is a Buddha seated in front of a Dharma wheel at the base of a bodhi tree (Ficus religiosa), the type of tree under which Buddha sat when he gained enlightenment. I have no idea who his chums are sitting around the edge down below. Neither can I tell you the meaning of the white sticks piled up round about the place. I should have a consulting Buddhist on hand for these moments, I quite realize, but I’m surrounded by Catholics at the moment so we’ll just have to manage. The group in the next pic is quite elaborate, to the point that one hardly knows where to introduce oneself first. I’d go for the Buddha using the double abhayamudra, the one with both hands raised, palms facing outward, since that posture and the stories associated with it have always seemed to me especially evocative and it’s one of the least common mudras in Buddha figures, for what reason I know not. Outside Chiang Mai at Huay Tung Tao, a reservoir lake with wonderful recreational facilities and lakeside huts where you can have your lunch, there’s a colossal Buddha with the double abhayamudra that comes immediately to my mind when I think of the posture and what it means — the repulsion of fear and protection from the rages of Nature. The protective nature of the mudra seems especially appropriate to the figure’s position in this group since it stands watch over the reclining Buddha, in his last moments on Earth before entering parinirvana.

The next pic struck me because of the placement of the Buddha figure in relation to the surrounding buildings. When I came across it for the first time I had the same reaction I would have to a fellow visitor whose path I had crossed. In that spirit, I said in my mind as I moved past it, “Lovely day for a walk, isn’t it, enjoy the sights.” I took as my response the Buddha smile on the figure’s lips, which seems so apt a response to so many things in life.

The walking Buddha is a free-standing figure in the grounds with lovely landscaping all round. The figure is shown walking because he is busy going about the countryside sharing his knowledge after reaching enlightenment. His right hand is in the abhayamudra, the mudra of repelling fear or of the state of fearlessness, a protective gesture. At the base of the statue were many offerings of flowers and fruit in addition to notes scribbled with petitions to the Buddha and pasted onto the surface of the base. Seeing such things makes it all seem so much more immediate, since evidence is present that the daily lives of people are intimately involved with this teaching.

Rather than recline in anticipation of parinirvana, however, we’re going to enter the last tour of our multiple agenda, designed for those who just want a lovely place to hang out. There’s an enormous number of places to do just that in the complex. Since the visitor number always appears to be low, save on those major feast days of the year when the crowds will gather, I expect, you can wander freely and choose your own perch for quiet contemplation, lingering observation or whatever else you choose as an occupation for the mind and senses. Here are some of the spots I found most congenial:

There are many more pics of other places where I enjoyed spending time on the temple grounds, and I’m sure your list would look different but be equally handsome as a set of spots to park yourself as you soak up the atmosphere and drink in the sights.

To close, I leave you with this image, mentioning no referent in comparison and with a slight Buddha-like smile on my lips despite my unenlightened state 🙂