March 2019

The second part of this two-part post on Slavic Baroque composers focuses on the High Baroque. Both Poland and the Czech lands were active centers of musical culture in that period so the list includes some names who are decidedly Big Deals. One such composer, Jan Dismas Zelenka — for long years a personal favorite of mine — has undergone such a revival in the last 20 years that he now rightfully takes his place along other musical luminaries of the period like Telemann and Bach. If you find Russians underrepresented in the list, blame it on the fact that all the big names in Russia were foreigners, largely Italians. I have only one Russian in the list — sorry, I did my best. 🙁

The second part of this two-part post on Slavic Baroque composers focuses on the High Baroque. Both Poland and the Czech lands were active centers of musical culture in that period so the list includes some names who are decidedly Big Deals. One such composer, Jan Dismas Zelenka — for long years a personal favorite of mine — has undergone such a revival in the last 20 years that he now rightfully takes his place along other musical luminaries of the period like Telemann and Bach. If you find Russians underrepresented in the list, blame it on the fact that all the big names in Russia were foreigners, largely Italians. I have only one Russian in the list — sorry, I did my best. 🙁

![]()

Jan Josef Ignác Brentner (Czech, 1689-1742)

Brentner is another example of a buried gem unearthed only in the 20th century through the revival of Baroque composers in the Slavic lands. There’s precious little information on his life. The Wikipedia page on him (here) is about as good as it gets:

Jan Josef Ignác Brentner was born into the family of the mayor of the small town of Dobřany in Western Bohemia. What we know about him comes mostly from time he spent in Prague, from 1717 to about 1720, where he published at least three major volumes of music. Brentner’s opus 1 is a collection of 12 sacred arias for voice, strings, and continuo, Harmonica duodecatometria ecclesiastica seu (1717), popular enough to demand a second printing in the 1720s. In addition, Brentner published a collection of six offertories for chorus, strings, and continuo entitled Offertoria solenniora (1717) as his opus 2 and a collection of six church sonatas, Horae pomeridianae seu Concertus cammerales (1720) as his opus 4. If Brentner published an “opus 3,” it has never been accounted for. Brentner’s patron was Raymond Wilfert, abbot of the Premonstratensian (Norbertine) monastery in Teplá, located in Bohemia but administered out of Austria. Scholars agree that most of Brentner’s music was first performed in Teplá under Wilfert’s direction, excepting his funeral motets, which were written specifically for the Brotherhood of St. Nicholas Church in Prague. Brentner died in his home town of Dobřany.

Although a great many of Brentner’s works are known to be lost, a scattering of manuscript copies survive throughout the Czech lands and a large number of them are located in the Music Archive of the Bendiktinerstift in Göttweig, Austria. Still others have turned up, in modified versions, in Bolivia; no one knows how Brentner’s music managed to travel to South America. Registries of lost collections belonging to provincial churches in Eastern Europe bear witness to Brentner’s works that are no longer extant; however, the library at Teplá cathedral—the second largest historical library in Bohemia—may contain music by Brentner as yet undiscovered, as its store of music manuscripts remain uninvestigated.

Excuse me, BOLIVIA?? Oh man. Talk about weird. The guy stays for his entire life in an ambit of about 60 miles from the place where he was born and his music ends up in BOLIVIA?? That sounds like something for The Twilight Zone or Black Mirror. Mind you, his music deserves to be spread to the four corners of the Earth because it’s excellent, fully the equal of anything produced in Germany or Austria in the period. If you think I’m making up stories there are now excellent recordings to make a completely convincing case for that assertion, so you needn’t limit yourself to taking my word for it.

Given that Brentner lived for 54 years and was musically active for his entire adult life, his list of compositions must be as short as it is due to massive loss of original material or the fact that nobody has yet combed through the music archive of Teplá cathedral. When one considers the often recherché subjects of doctoral dissertations in musicology these days, it seems inevitable that somebody will eventually do us all a favor by discovering what music of Brentner’s lies hidden in those dusty tomes. When you see the size of the Abbey it’s obvious there are plenty of places to look:

Here’s the list of Brentner’s compositions from the Wikipedia page:

- Harmonica duodecatomeria ecclesiastica op. 1 (Prague 1716)

- Offertoria solenniora op. 2 (Prague 1717)

- Hymnodia divina op. 3 (Prague 1718)

- Horae pomeridianae, Concertus cammerales 6, op. 4 (Praha 1720)

- Laudes matutinae (lost)

One of the best recordings is “Concertos & Arias. Music from Eighteenth-Century Prague” by Collegium Marianum directed by the Baroque flautist Jana Semerádová, available on the Supraphon label. Both the music and the performances are stunning. The works from Harmonica duodecatomeria ecclesiastica are sung by the fantastic Czech soprano Hana Blažíková. The orchestral pieces from Horae pomeridianae are enough to make Telemann turn green. The first time I heard them I was gobsmacked and knew I’d found another of those composers who’ll accompany me to the grave. Kudos to Collegium Marianum, as well, for top-notch performances done with all the elegance and style we’ve come to expect from the best European early music groups. The Czech Republic’s coterie of such groups has definitely taken its place squarely on that map.

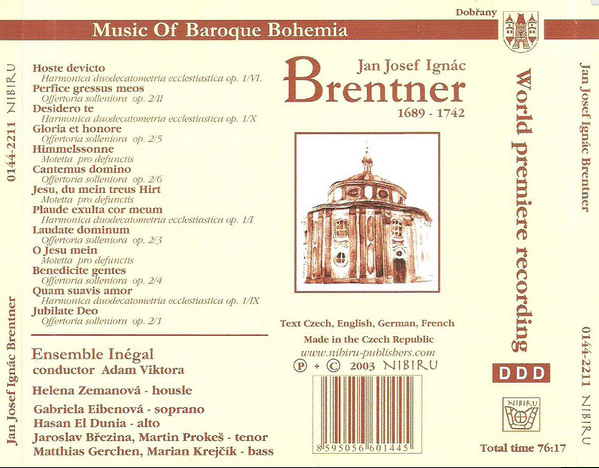

The other major recording of Brentner’s works is by Ensemble Inégal under their director Adam Viktora. It’s on the Nibiru label — here’s an image of the CD verso:

The soprano, Gabriela Eibenová, has made a name for herself with Viktora’s group and she’s very good. She has a more coloratura timbre to her voice than Blažíková but she uses it extremely well and is absolutely bursting with energy. Two thumbs up.

There’s a full listing of recent recordings in the Wikipedia article, including some rather obscure ones that I imagine would be hard to lay hands on unless you have a runner in Eastern Europe. If you do, then keep it to yourself or you’ll just make the rest of us envious. 🙂

![]()

Bohuslav Matěj Černohorský (Czech, 1684-1742)

Biographical information on Černohorský is not easily come by, so back to Wikipedia we go (here):

He was a son of a Nymburk cantor named Samuel Černohorský. From 1700 to 1702 he studied philosophy at the Prague university. In 1704 Černohorský became a member of the Conventual Franciscans; later, in 1708 he was ordained as a priest Nevertheless, in 1710 Černohorský was expelled from Czech lands for ten years, and he left for Assisi, Italy. From 1710 to 1715 he worked as an organist in the Basilica of San Francesco d’Assisi, and probably studied counterpoint with Giuseppe Tartini. He was called “Padre Boemo” in Italy. After the expiration of his punishment, he came back to Prague, where he devoted himself to teaching. Among the important pupils of the “Černohorský school” are Josef Seger, František Tůma and others. In 1731 he came to Italy again, and worked as an organist in Padua. Černohorský died in Graz in 1742.

What? Expelled? Hmmm … a bit of digging turned up this info from allmusic. com by Robert Rawson:

He was born in Nymburk and later studied philosophy at Prague University. Although he received his early education from the Jesuits he took orders with the Franciscans. After leaving university in 1710 he left Prague and went to Italy. This greatly upset his Franciscan guardians who expelled him for 10 years and stripped him of all titles and privileges. Such a reaction seems severe since he had received an invitation directly from the Franciscans in Rome who restored his titles taken by the Czechs and appointed him chief organist at St. Francis in Assisi.

After his 10-year exile expired, he was summoned back to Prague, but opted for Padua instead. He finally made it back to Prague in 1720 where he then produced the ambitious Litaniae Lauretanae to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the Catholic victory at White Mountain. The piece requires large forces (strings, chorus, four trumpets, and tympani) and features well-wrought fugal sections and energetic instrumental writing. This time in Prague saw Cernohorsky reach the height of his achievements, he was given numerous awards and accolades and was a highly sought after teacher of organ and composition.

This glory, however, was short lived. In a dispute with the Franciscans, he denied them his family inheritance and was exiled to Horazdovice in South Bohemia and, yet again, stripped of his titles. It was during this exile where he composed his most famous work, the five-part motet Laudatur Jesus. Disillusioned, he requested permission to return to Padua, where he resumed official duties. He remained there until 1741, when, for unknown reasons, he requested leave to return to Prague. He never made it back to Prague, but stayed the winter in Graz, where he died in February 1742. His inability to make a life for himself in Bohemia was a cause of great sorrow; he wrote: “you see here an open breast without a heart, but have you ever seen one with an open breast and no heart who could continue living?”

Jeez, school of hard knocks or what … sounds like he should have stuck with the Jesuits. Still, ending up in Assisi is not a bad exile — I can think of far worse places to spend 10 years. But apparently the motherland always calls, just as it did for Johann Rosenmüller (1619-1684) who had to hightail it out of Leipzig at the peak of his fame following some funny business with choirboys. He ended up in Venice, stayed for 20 years but eventually accepted a post in Wolfenbüttel — i.e. Nowheresville, despite its being the seat of the Dukes of Braunschweig-

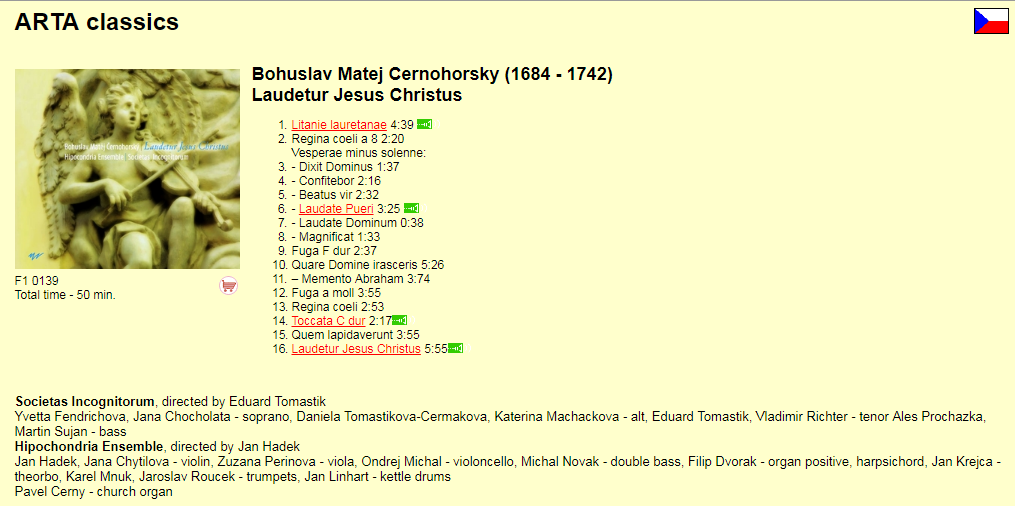

In the interests of transparency I’ll admit outright that I don’t care for Černohorský’s vocal works. They’re monotonous through a lack of both melodic invention and rhythmic variety. The organ music, however, I find much more satisfying. The recording of his music I have includes both vocal and organ works. It’s a collaboration of Hipochondria Ensemble and Societas Incognitorum on the Arta label. Here’s an image of the verso with the tracklist:

It’s not available on Amazon so it would have to be chased down in Europe, I expect. There are some tracks from the recording on YouTube, which is cheating, I know, but hey, you gotta do what you gotta do. My lips are zipped if you download — mum’s the word. 🙂

![]()

Grzegorz Gerwazy Gorczycki (Polish, ca. 1665 to 1667 – 1734)

Gorczycki is another of those lost treasures that only now comes again to attention, but not nearly to the degree his music deserves. From the Wikipedia page on him (here) comes this biographical information:

Born in Rozbark near Bytom in Silesia then Habsburg Monarchy around 1665, little is known of his early life. Similarly little is known about his musical education; however, it is known that he attended the University of Prague, where he graduated from the department of Liberal Arts and Philosophy, and then attended the University of Vienna, where he gained a licentiate in theology. He arrived in Kraków in 1689 or 1690, where he then attended the Catholic Seminary. He was ordained on 22 March 1692.

Following his ordination, he was appointed to the academy for missionary priests in Chełmno in Pomerania, where he lectured in rhetoric and poetry, as well as conducting the local orchestra. After two years, he returned to Kraków, where he was appointed curate of the cathedral, and performed in the cathedral orchestra. He was appointed conductor on 10 January 1698, and remained in this position until his death on 30 April 1734.

The earliest recorded information on any of Gorczycki’s works comes from 1694, but he must have written a substantial amount before 1698 in order to be appointed Kapellmeister. Unfortunately none of his compositions were ever published during his lifetime, so most of them have been lost; 39 works can, however, be attributed to him with surety.

Once again, the “L” word — lost. We come across that four-letter word so often with regard to composers from the Baroque period. It’s enough to make your hair stand on end. Gorczycki is one of the miraculum sui generis composers who spring apparently fully formed from the forehead of the Muses. Vienna was the musical centerpoint of the area since it was the seat of the Habsburg Monarchy, so perhaps during his time there he picked up some lessons with a master composer and tucked the notes into his luggage when he returned to Poland.

Regardless how he pulled it off, he ended up being a composer with gifts and accomplishments fully equal and similar in nature to those of Francesco Cavalli (1602-1676), whose sacred music is also extremely melodious and inventive. Cavalli was famous primarily for his operas, not for his church music, so when he wrote sacred music he retained the sense of melody and drama native to him as a composer for the theatre. It sounds crazy to compare Gorczycki to Cavalli on the basis of life context, I quite realize, but listen to the music of both composers and I think you’ll find that I’m not just making up tall tales by suggesting a similarity in compositional approach.

I know of only one recording dedicated solely to Gorczycki’s work but some works are included in other recordings of Polish Baroque music by anthology. There are a couple recordings available on Amazon — including another in The Sixteen’s series on the Polish Baroque, which I can’t recommend save for the advantage of having examples of Gorczycki’s music otherwise hard to come by. There are several things available on YouTube, as well, including performances of several lovely concerted motets such as “In virtute tua” (here) and “Laetatus sum” (here) which sound the most Cavalli-esque of all to my ears.

Finally, here’s a work list from the Polish website Completorium (here) that offers excellent material on Polish composers of the Baroque:

- Concerti:

- Completorium

- Completorium (ii), (another entry in the thematical catalogue) mentioned in Kraków inventory

- Conductus funebris

- Crudelis Herodes

- Deus tuorum militum (2 versions; one in 2 parts, with Innocentes pro Christo intontes following)

- Gratuletur ecclesia

- Illuxit sol iustitia

- In virtute tua

- Jesu corona virginum

- Justus ut palma florebit

- Laetatus sum

- Litaniae de providentia divina

- Os iusti meditabitur

- Tristes erant apostolic

- Missae:

- Missa De Conceptione B.V.M. (Propers only)

- Missa paschalis

- Missa ‘Rorate coeli’ (i) (with introit Missa ‘Rorate coeli’ (ii) (Propers only)

- ‘Rorate’; without Credo)

- Motets:

- Alleluja. Ave Maria

- Alleluja. Prophetae Sancti

- Ave Hierarchia

- Ave maris stella

- Ave virgo speciosa

- Dignare me

- Iste confessor Domini

- Jesu redemptor omnium (3 different versions)

- Judica me Deus

- Laetare Jerusalem

- O rex gloriae Domine

- O sola magnarum urbium

- Regina coeli laetare

- Sancte Deus, sancte fortis

- Sepulto Domino

- Sub tuum praesidium

- Te Joseph celebrant

- Tota pulchra es, Maria

- Vidi aquam

- instrumental:

- (doubtful – may not be by Gorczycki) Polonez balowy

- Lost works:

- Ouverture ex D; lost, mentioned in Wielu? inventory

- Litaniae de SS Sacramento, ex A; lost, mentioned in Wielu? inventory

Everything of Gorczycki’s I have heard is fantastic so it’s worthwhile to chase his music down by whatever means you can and have a listen. You’ll be glad you did.

![]()

František Jiránek (Czech, 1698-1778)

Jiránek is a recently unearthed Czech composer who by example reminds us of the treasures still lying hidden in the archives of Europe. I’ve said it before but I’ll say it again: why is it so bloody hard for us human beings to keep track of our stuff, especially our important stuff? Any answers? If Jiránek had been a provincial hack who wrote a couple country dances for fiddle it would perhaps be more understandable how he got deep sixed directly after his death, but that’s hardly the case. He was a fantastic composer and likely studied with Antonio Vivaldi, one of the Big Names in European music of the Baroque period (although I’d rather have a root canal than listen to Vivaldi — but that’s another story). Since he has so recently been yanked out of total obscurity it’s not surprising that we have very little biographical information on him. Here’s what little I find in his Wikipedia page (here):

Jiránek was born on 24 July 1698 in Lomnice nad Popelkou (Northern Bohemia, present-day Czech Republic). His parents were servants of the Counts of Morzin; František also started to work for them as a musician. Count Václav Morzin sent him to Venice in 1724 to improve his musical abilities. His teacher was probably Antonio Vivaldi himself. Count Václav Morzin was a very important supporter of Vivaldi (Vivaldi dedicated to him his famous Four Seasons).

In 1726 Jiránek came back to Prague and worked as a violinist in the Prague ensemble of Václav Morzin.[1] In this ensemble worked also Antonín Reichenauer and Johann Friedrich Fasch. After the death of Václav Morzin in 1737 Jiránek left Prague and was employed by the Prime Minister of Saxony, Heinrich von Brühl in Dresden. In Dresden his work was informed by the coming Classical music. After the death of Heinrich Brühl in 1763 he retired and died in 1778 in Dresden.

Dresden was a center of one of the major musical courts of Europe at the time with the likes of Johann Adolph Hasse as Kapellmeister, earning an astronomical salary although he was hardly ever there. So by going to Dresden Jiránek was hitting the big time. Like his compatriot Jan Dismas Zelenka (see below) he stayed there for the rest of his life, living for 15 years in retirement as an ethnic Czech in a German city. The attractions of Dresden were obviously great enough to keep him there even after the end of his official position in the musical establishment. When you see what it was like there, it’s no wonder:

There’s only one recording of Jiránek’s music and it’s a gem, done by Collegium Marianum under the direction of Jana Semerádová. This blurb from the website of one of the performers, the German oboist Xenia Löffler (here), gives an overview:

The Baroque composer František Jiránek (1698–1778), nicknamed the “Czech Vivaldi”, served as a violinist of Václav Morzin’s court orchestra. Having only discovered his music a few years ago, researchers are now identifying his works, as the authorship of some of them is still unclear, with some sources ascribing them to Jiránek and others to Vivaldi, his teacher in Venice. Jiránek’s music has also enjoyed growing interest on the part of musicians. Besides Jana Semerádová’s Collegium Marianum, its champions include the brilliant Italian bassoonist Sergio Azzolini and the superlative German oboist Xenia Löffler. All the ambiguities as to its origin and a few specific requirements (for instance, employment of the viola d’amour, a scarcely used instrument, in the Triple Concerto in A major) notwithstanding, the CD features vivid, ebullient and virtuoso music, pieces previously unrecorded and performed in a top-notch way.

She’s said it all, I needn’t elaborate. The point about Jiránek being stylistically similar to Vivaldi is not ill-made — more’s the pity for those of us who aren’t wild about Vivaldi’s music. For those Vivaldi aficionados out there, Jiránek will be right up your alley. I’m glad I have the recording for the sake of having examples of Jiránek’s music performed exquisitely by Collegium Marianum, but I find myself reaching much more often for the CD of Brentner if I’m completely honest. De gustibus non est disputandem. 🙂

![]()

Jiří Ignác Línek (Czech, 1725-1791)

Let’s get the biographical information out of the way first. Most of what I found is in Czech, which is not big deal to me since I read Czech, but I don’t think that’s a characteristic most readers are likely to share. So here’s the (measly) info from the Wikipedia page (here):

… a renowned Czech late-Baroque composer and pedagogue, said to have composed over 300 works in his lifetime. He is especially noted for his Christmas pastorals and for his initiation of a literary brotherhood within Bohemia.

He was born at Bakov nad Jizerou, Bohemia. In the period official register, his name was entered as Linka, but he always signed himself Linek. He studied at the Piarist gymnasium in Kosmonosy; later, he studied composition with Josef Seger. From 1747 to his death, he was a teacher, choirmaster and member of the literary fraternity in Bakov nad Jizerou. He died of tuberculosis; his gravesite is unknown.

There’s a much longer entry for Linek in the Czech equivalent of Grove’s Dictionary, the Český hudební slovník osob a institucí (webpage here). In it we learn that in 1747 Linek was named cantor of the church of St. Bartholomew (Svatý Bartoloměje) on the retirement of his father from the post. He spent the rest of his life in the town where he was born and raised. Bakov nad Jizerou is about 74 km (46 miles) northeast of Prague, so it’s well within the cultural ambit of the capital. Here’s a pic of the church in which he worked for so many years:

I have only one recorded work of Linek’s embedded in an anthology and it’s not even of the type of music for which he was well-known. The recording is “Coronation Mass for Leopold II in Prague, September 1791” performed by the Wiener Akademie under the direction of Martin Haselböck. The CD dates from 1992, which is ancient, so if you want to hear it you can catch it on YouTube here, or just the Linek pieces (brass intradas) here. They’re very fine compositions and I hope Linek gets caught up in the frenzy of Baroque composer rediscoveries going on in Europe so that we have more recordings of his music. I’d be well pleased with myself had I been out in the boondocks for most of my life writing music half as accomplished as Linek managed to compose. We hayseeds have to stick together LOL.

![]()

Antonín Reichenauer (Czech, 1694-1730)

With a name like Reichenauer it’s not difficult to figure out that there was a German or an Austrian somewhere in the woodpile, although Reichenauer was indeed Czech, born in Prague and spent all his life in Bohemia. But there were Germans and Austrians all over the place, since it was part of the Habsburg Empire, so somebody must have done some ethnic bridging. Hey, it happens.

Nothing is known about Antonín Reichenauer’s childhood and upbringing. The first records are of his post as choirmaster in 1721 at the Dominican church of St. Mary Magdalene in Malá Strana in Prague. He was also associated with the chapel of Count Wenzel Morzin, for whom he regularly composed works. According to some sources, he also worked for Count Franz Joseph of the House of Czernin. In 1730, at the end of his life, he became an organist at the parish church in the southern Bohemian town of Jindřichův Hradec. He died there less than a month after taking office, aged 35 or 36.

Many of Reichenauer’s works have survived in archives and libraries in Bohemia, Silesia, Saxony and Hesse. The existence of his works in various collections outside Prague suggests a popularity outside of his homeland. The library of the monastery in Osek lists a total of 40 works of sacred music by Reichenauer from the years 1720-1733.

Reichenauer was known as a prolific composer of church music. His musical output was strongly influenced by the school of Antonio Vivaldi, whom he often mentioned in his works. He was the first Bohemian composer of a pastoral mass (his “Missa Pastoralis” in D major was written in around 1720). A series of concertos for violin, oboe, bassoon and cello, as well as orchestral overtures and trio sonatas are preserved to this day.

Vivaldi again, what’s up with Vivaldi in the Czech lands? Enough with the Vivaldi, oy gevalt! If you asked me whose music Reichenauer’s most reminds me of, Vivaldi is not the name I would utter. Not in a million years. The name that would spill across my lips is: Johann Friedrich Fasch (1688-1758). But I’m not a card-carrying musicologist so I hardly expect you to take my word for it. Have a listen yourself — a couple instrumental concertos of Fasch, then a couple by Reichenauer. I’m not as crazy as I might sound. I couldn’t possibly confuse either of them with Vivaldi — and even if I could I’d downplay it as much as possible since there’s no need to be insulting. No doubt the similarity between the musical idioms of Reichenauer and Vivaldi has been established by musicologists of unimpeachable repute and fierce academic prowess, so I’ll just keep my Great Unwashed mouth shut. You’re on your own, babes. 🙂

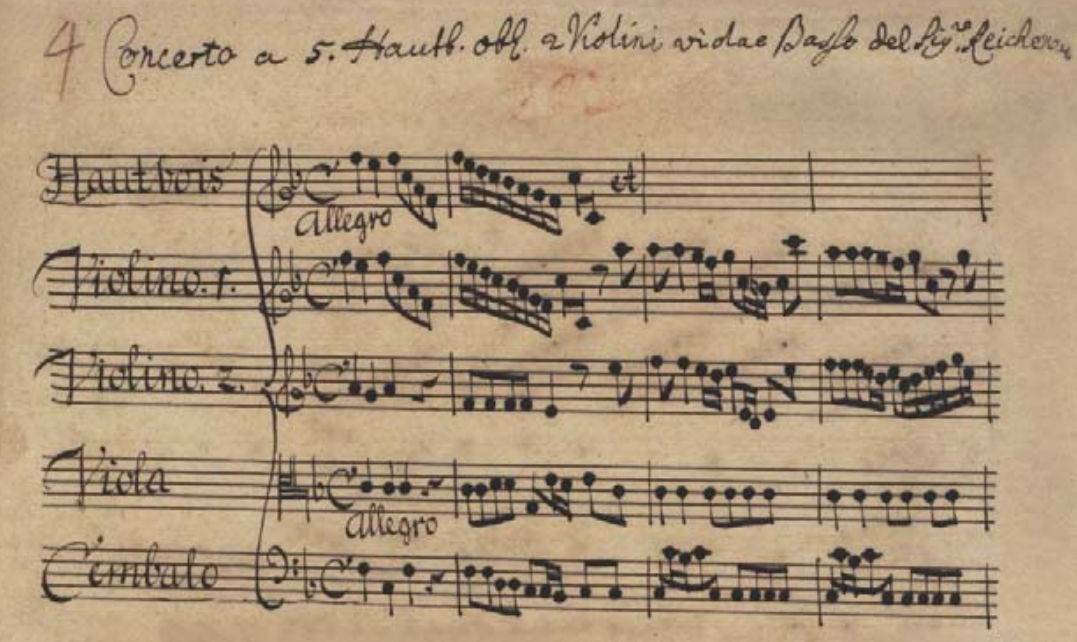

Here’s the title page from one of his manuscripts for an oboe concerto:

Because Reichenauer worked at two major court establishments in Prague a lot of his music has survived in archives. He got on the fast track in the Baroque composer revival as a result, so we have recordings of his works in a degree of amplitude that for someone like Linek will probably be a long time coming. The two recordings I have are volumes one and two of orchestral music and concertos performed by Musica Florea under the direction of Marek Štryncl, who has the remarkable quality of looking about 12 years old when he stands in front of an ensemble despite being now in his 40’s. He must have found the Fountain of Youth. Jealous …

Musica Florea is one of the major early music ensembles of the Czech Republic in the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis tradition (original instruments, historical performance practice, that sort of thing). The recordings are excellent and highly to be recommended. The bad news is that the CDs are “currently unavailable” when last I looked on Amazon. Volume two is available on YouTube here. It’s worth having a listen to acquaint yourself with this fine composer — who btw does NOT sound like Vivaldi. 🙂

![]()

Václav Karel Holan Rovenský (Czech, 1644–1718)

The Český hudební slovník (= Czech Music Dictionary) (webpage here) has no entry for Rovenský, which I find completely inexplicable. I can’t begin to imagine why there’s no information on him since his music has been revived sufficiently to figure in two modern recordings. The Wikipedia page on Rovenský (here) is brief and tells about all there is available on him, so here it is:

He had been organist in Turnov and Rovensko pod Troskami (where he was also cantor) from 1668 and in Dobrovice, near Mladá Boleslav, in 1679–1680. During his tenure at Vyšehrad he may have taken a pilgrimage to Rome and sometime in the early eighteenth century he lived a prayerful and hermit-like existence at Waldstein Castle near Turnov.

His magnum opus is Cappella Regia Musicalis (Prague, 1693), containing 772 pieces, which was almost certainly the fruit of his 12-plus years as a provincial cantor. The publication coincides with his appointment as organist at Vyšehrad in Prague, though he may have been in the city for some time before that. Cappella Regia Musicalis is a massive collection of hymns, sacred and festive songs, and all manner of musical settings of almost all central parts of the Roman Catholic liturgy, all printed primarily in the Czech language. It is difficult to tell just how much of the collection was composed by Holan himself (though it is clear that many other composers are represented), and some of the songs and other pieces are clearly much older, such as the anonymous fifteenth century Czech settings of the Passion. Curiously, the collection also contains many earlier Protestant and even Hussite songs, making it something of a survey of Czech sacred song to date. Unlike most other Czech hymnals, many pieces in Holan’s collection also included basso continuo and even obbligato instruments such as violins, viols, and trumpets. Another curious feature of this rather amazing publication is that no two surviving copies are alike, leading to suspicions that they may have been made-to-order. It would seem that Johann Heinrich Schmelzer was familiar with it, since a (greatly expanded) German-language version of one of the pieces circulated under his name. Sections of Cappella Regia Musicalis were continually copied and reprinted throughout the ensuing centuries and, in some quarters, have been the basis for many Czech hymnals.

Turnov and Rovensko pod Troskami are both in the Český ráj (= Bohemian Paradise) in the northeastern area of the Czech Republic. Both are small but handsome provincial towns near one of the country’s areas of great natural beauty (info here). Here are some pics of the squares of both towns (Turnov first, then Rovensko pod Troskami) and a pic of Trosky Castle, the major landmark of the region:

Rovenský went from his provincial cantorship to the Royal Court, which is what Vyšehrad is — the hill on which the royal palace and St. Vitus Cathedral sit perched so prettily. The move put Rovenský at the heart of the Czech musical establishment and opened channels to the Imperial Court in Vienna. That explains the connection with Johann Heinrich Schmelzer (ca. 1620-1680). If Schmelzer knows your stuff then you have arrived, because he was a Big Deal at the Viennese Imperial Court and eventually became Kapellmeister there shortly before his death.

It’s unclear exactly how many of the compositions in his collection are by Rovenský himself. He may unbeknownst to us have been a more ambitious composer in the manner of the High Baroque, writing music in the genres common to the period — concertos, orchestral suites, etc. — but his collection is on the order of folkmusic. The pieces it contains are largely religious songs like the ones Orlando Gibbons wrote for his collection “Hymnes and Songs of the Church” (with such spine-tingling delights as “Come, Kiss Me With Those Lips of Thine”). They’re simple as the day is long but very beautiful in both the singing and the hearing.

From ArkivMusik (webpage here), my go-to site for information on recordings, I find only two recordings with music of Rovenský. Of the two I only own one, “Rorate Coeli: Music From Eighteenth-Century Prague” by Collegium Marianum on the Supraphon label. As luck would have it, the ArkivMusik page on Rovenský has a review by Bertil van Boer from Fanfare that provides a bit more biographical information:

As the fine booklet notes by Václav Kapsa state, the two native composers, Václav Karel Holan Rovenský (c. 1644–1718) and Antonín Reichenauer (c. 1694–1730), are little-known names, even in lexica. The former was from the small Bohemian town of Rovensko pod Troskami (hence the appendage to his last name), and worked in a number of smaller places in and around Prague as an organist before undertaking a pilgrimage to Rome in 1674. There he was influenced to compose and publish a hymnal, Capella Regia Musicalis, which contains some of if not the first popular sacred music in Czech. As a monk he eventually decided upon the acetic life of a hermit, living out his days in solitude at Valdštejn.

I’m especially fond of Rovenský’s songs because they’re in Czech. They represent one of the few authentic Czech-language musical examples from the 18th century, when Czech was considered a language spoken primarily in the boondocks by rubes and hayseeds. Only in the later 19th century after the Czech Revival reclaimed the language as a national asset did Czech once again take its proper place beside German. The songs would be lovely even if sung in a different language, however, so it’s worthwhile to have a listen. If you can’t track down the CD there are several songs available on YouTube (here).

![]()

Luka Ignacije Antunov Sorkočević (Croatian, 1734-1789)

Sorkočević comes at the tail end of the Baroque period and some people might take issue with my placing him on the list because his musical idiom could easily be placed in the early years of the Classical era. In my opinion he has a foot in both worlds and represents a transitional figure, so I feel perfectly justified in claiming him for inclusion here. Besides, I’m not a card-carrying musicologist with an academic reputation to defend so I can say what I want. 🙂 And the Wikipedia on him (here) backs me up:

Luka (Lukša) Sorkočević was born in Dubrovnik and received an extensive education. His music teacher was the Italian composer Giuseppe Valenti, who was maestro di cappella of Dubrovnik Cathedral in the 1750s. He continued his education in Rome where he studied musical composition with Rinaldo di Capua. Later, Sorkočević married a girl from the Luccari (Lukarević) family and held several posts in various branches of Dubrovnik politics and society. During his relatively brief stint in Vienna as the ambassador to the imperial court he met several leading composers of his time, like Gluck and Haydn, and the famous poet Metastasio – a valuable experience for his later life and work. With serious health problems, he committed suicide by throwing himself from the third floor of his palace in Dubrovnik in 1789, at the age of 55.

What a horrible end for so cultured and respected a man. Just FYI, during the whole of the 18th century Dubrovnik with its environs formed a separate state called the Republic of Ragusa, which was a fascinating political entity during its long life from the Middle Ages until 1808 when Napoleon (that creep) invaded and occupied it. Rebecca West gives a long and detailed history of it in her book Black Lamb and Grey Falcon. It had close ties to Venice, hence the Italian training that Sorkočević received. He was a very good composer and his orchestral music is definitely worth a listen.

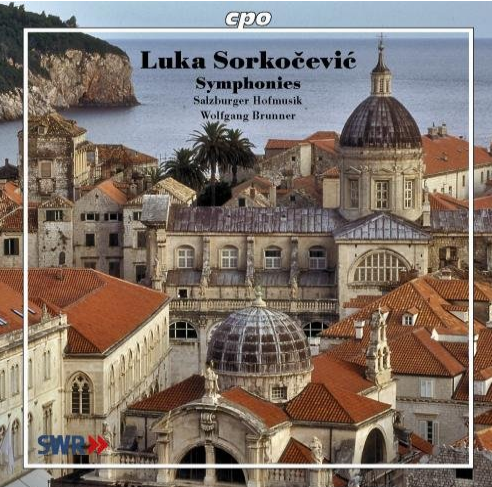

There’s only one good (IMHO) recording of Sorkočević’s music, symphonies performed by Salzburger Hofmusik directed by Wolfgang Brunner on the CPO label. It’s a great ensemble and they really bring the music alive. The CD is available on Amazon — here’s a pic of the cover:

![]()

Vasily Polikarpovich Titov (Russian, ca. 1650-ca. 1715)

This is called “scraping the bottom of the barrel,” not because Titov is undeserving of attention as a composer but rather because finding anyone Russian associated with Baroque music in Russia is a bit of a dig. Given that fact it shouldn’t surprise us that biographical information on Titov is hard to come by. The Wikipedia page (here) is about all we have to hand:

The scant biographical materials indicate that Titov was born in the 1650s. He joined Tsar Fedor’s choir, the Gosudarevy Pevchie Diaki (Государевы Певчие Дьяки, The Tsar’s Singers) when he was in his twenties; his salary is recorded in 1678. He quickly rose to prominence as both singer and composer. In the 1680s he collaborated with Simeon Polotsky (a famed churchman, man of letters and tutor to the children of Tsar Aleksey Mikhailovich), composing musical settings of Polotsky’s psalter and an almanac of sacred poetry. In the 1680s Titov also joined Tsar Ivan’s choir.

When Tsar Fedor died in 1682, Titov retained his position in Tsar Ivan’s choir. Tsar Ivan died in 1696 and the choir was disbanded in 1698. It is not known precisely what happened next to Titov. He may have taken up a position as choir master in a church of the Moscow Kremlin and/or head of a music school in Moscow. Nothing is known of his last years, except that he wrote some compositions associated with the Battle of Poltava in 1709 and died soon after that.

Do you feel well-informed? If you don’t, join the crowd. Since the Church was essentially marginalized into invisibility during the Soviet era, no scholarship has brought out the hidden treasures that doubtless exist in Russian ecclesiastical music of the Baroque period. Since Titov wrote over 200 works there’s obviously a lot of work to do in that department. Let’s hope somebody does it before the archives are lost entirely to posterity. Something tells me Putin doesn’t pay too much attention to the preservation of old manuscripts in the archives of monasteries.

You’ll search in vain for recordings of Titov’s works. To hear one of them I suggest you go to the YouTube video (here) of the choral piece “Glory, Only-Begotten Son” performed by the Estonian Philharmonic Chamber Choir. It’s a cappella, a very lovely work to be sure and a hint at what other delights await discovery in the composer’s oeuvre.

The music scene in Baroque Russia was entirely overrun by Italians — and not by musical nobodies who couldn’t find a job in Italy. Quite the opposite. Here’s a list of some of the composers active in St. Petersburg during the High Baroque period from a list entitled “Great Italians in St. Petersburg” on the website saint-petersburg.com (here):

Giovanni Paisiello (1741-1816)A Neapolitan composer of opera who influenced Rossini and Mozart, Giovanni Paisiello worked in St. Petersburg at the court of Catherine the Great for eight years as kappelmeister, and wrote some of his most famous operas there.Baldassarre Galuppi (Composer, 1706-1785)The Venetian Baldassarre Galuppi was one of the greatest opera composers of the 18th century. He served as kappelmeister to the court of Catherine the Great in St. Petersburg from 1765 to 1768, writing operas and sacred music.Tomasso Traetta (Composer, 1727-1779)Kapellmeister at the court of Catherine the Great from 1768 to 1775, Tomasso Traetta was an Italian opera composer of the Neapolitan school whose works were influenced by French composers, especially Jean-Philippe Rameau.

![]()

František Ignác Antonín Tůma (Czech, 1704-1774)

Tůma is one of the few Czech composers in this list who made a career largely in Vienna, the imperial capital of the Habsburg Empire that ruled over the Czech Lands. He attained to important positions in the Viennese musical establishment, as the biographical information from his Wikipedia page attests:

Tůma received his early musical training from his father, parish organist at Kostelec, and probably studied at the Clementinum, an important Jesuit seminary in Prague. He likely sang as a tenor chorister under B.M. Černohorský (an important composer and organist) at the Minorite church of St. James, and he is believed to have received musical instruction from him. Tůma then went to Vienna, where he was active as a church musician; according to Marpurg he became a vice-Kapellmeister at Vienna in 1722. Tůma’s name first appears in Viennese records in April 1729, when the birth of a son was recorded.

In 1731 he became Compositor und Capellen-Meister to Count Franz Ferdinand Kinsky, who was the High Chancellor of Bohemia. Kinsky’s patronage made it possible for him to study counterpoint with J.J. Fux in Vienna. He participated in the premiere of Fux’s opera Constanza e Fortezza along with Jiri Antonin Benda and Sylvius Leopold Weiss. In 1734, Kinsky recommended Tůma for the post of the Kapellmeister to Prague Cathedral, but his recommendation arrived too late and Tůma may have remained in Kinsky’s service until the latter’s death in 1741. In that year he was appointed Kapellmeister to the dowager empress, the widow of Emperor Karl VI. On her death in 1750, Tůma received a pension.

For the next 18 years he remained in Vienna and was active as a composer and as a player on the bass viol and the theorbo; he was esteemed by the court and the nobility, and at least one work may have been commissioned from him by the Empress Maria Theresa. After the death of his wife in about 1768, Tůma lived at the Premonstratensian monastery of Geras (Lower Austria), but in his last illness he returned to Vienna and died in the convent of the Merciful Brethren at Leopoldstadt.

There aren’t any cherry trees or axes nearby but even so I cannot tell a lie: I’m not fond of Tůma’s music. J. J. Fux (info here) was one of the most important teachers of the period and everybody who wanted to be somebody studied counterpoint with him, it seems. For some composers like Zelenka counterpoint studies with Fux led to a blossoming of creativity we see in the composer’s major works. I can’t say I find that to have happened with Tůma. Ditto for Johann Joachim Quantz, who also studied with Fux. But oh well, you win a few you lose a few, and far be it from me to sully the musical reputation of Tůma without providing detailed musicological underpinning for my arguments — which I’ll give a miss lest I bore you to tears. You can make your own determination from one of the recordings of Tůma’s music currently available.

I own two recordings, one of instrumental works and another of vocal works. The instrumental works consist of chamber sonatas and orchestral sinfonias performed by Concerto Italiano under the direction of Rinaldo Alessandrini. The group is among the Big Deals of early music performance and the rendition of Tuma’s music brings the ensemble’s full resources to bear. I can’t say I think the music lives up to the playing. Bad me.

The recording of vocal works includes a Stabat Mater and a Miserere together with some psalm settings. The performances are by the ensemble Currende under the direction of Erik van Nevel, on the Accent label. The playing and singing is faultless as you’d expect from Currende, which has a reputation for excellence. The music itself, however, reminds me of the studied turgidity one sees in statues of martyred saints in Mexican churches. If it’s pathos Tůma is after, you can bet your bottom dollar you’re in for some heavy-duty chromaticism, just like you’re likely to find large, bright red drops of blood issuing from the martyr’s wounds on a Mexican statue. The counterpoint is unsophisticated and sounds like something from Tůma’s exercise books during his study with Fux. We are not amused. But by all means, form your own opinion, somebody must think it’s the cat’s meow or there wouldn’t be two recordings available, right? Right. So go for it.

![]()

Pavel Josef Vejvanovský (Czech, c. 1633 or 1639–1693)

Vejvanovský is one of my heros not only because he was a fine composer but because he’s Czech to the core. He was born in Moravia and spent all his life in the Czech Lands, becoming in 1650 the Kapellmeister of the musical establishment of the Prince-Bishop of Olomouc at his fancy palace in Kroměříž — one of the major musical courts in Bohemia and now a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The Wikipedia page on Vejvanovský (here) gives us this information:

As a composer his output is uneven, but in his later works he was able to master most typical idioms of the day. He seems to have struggled with imitative counterpoint and his most compelling pieces are characterised by charming folk idioms and virtuosic brass writing. He composed in a wide variety of genres ranging from large-scale Mass settings and music for special feast days to more intimate sonatas and suites. In addition to his musical responsibilities, he also maintained the Bishop’s music library and was the primary copyist of the collection, with his hand appearing in hundreds of manuscripts. His own compositions circulated throughout central Europe, appearing in other Czech collections as well as in Germany and Austria. He seems to have made at least one visit to Austria with the purpose of copying and collecting music and it is largely thanks to Vejvanovsky that so much central-European music from the time is preserved in what is widely regarded as one of the most important collections of late seventeenth century music on the Continent.

Vejvanovsky must have been one of the greatest trumpet virtuosos of the age and his numerous compositions attest to his virtuosity. One of his more remarkable talents was the ability to play certain chromatic passages on the trumpet, which is not normally possible on the largely diatonic natural trumpet. Under Vejvanovsky’s direction the Bishop’s ensemble saw its heyday. Other musicians at court included Philipp Jakob Rittler, Heinrich Biber, and Gottfried Finger, the latter two employing certain characteristics of Vejvanovsky’s trumpet writing in their own compositions.

The Kroměříž palace musical establishment produced one superstar of the Baroque: Heinrich Ignaz Franz von Biber. Gottfried Finger has recently come into his own as well through resuscitation by the gambist Petr Wagner and his Ensemble Tourbillon, who’ve done fantastic recordings of Finger’s works that I’m delighted to own. So the Kroměříž musical establishment was a Big Deal and being its director meant that Vejvanovský hit the Big Time, although history has brutally robbed him of that honor. Hopefully his music will find broader revival in the future as Finger’s has done.

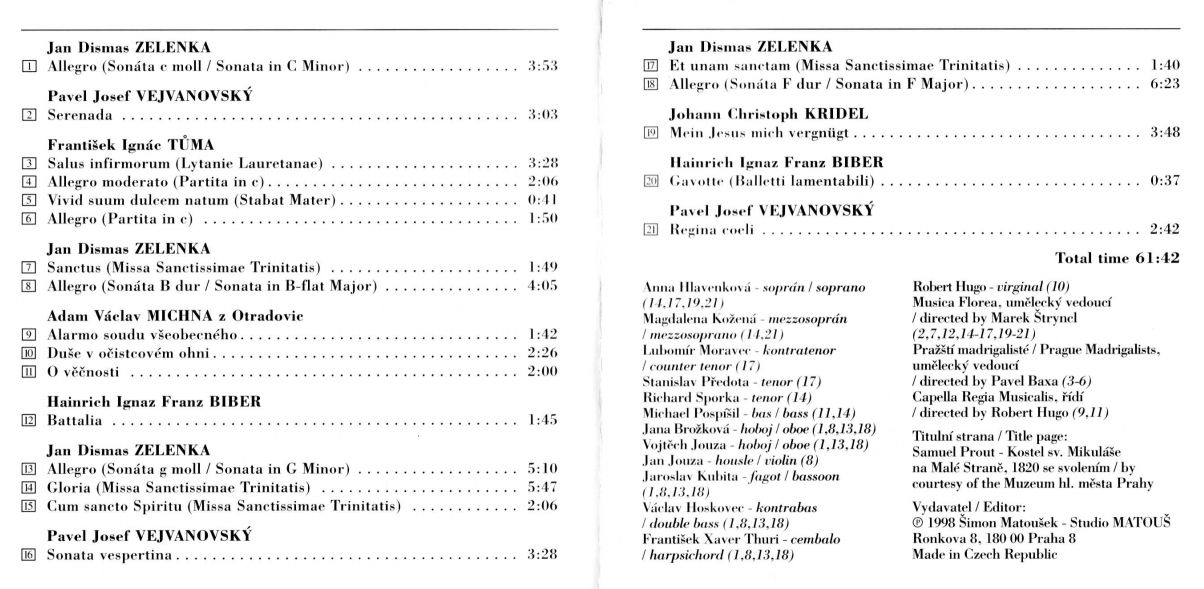

I’ve only found recordings of Vejvanovský’s music in anthology. The recording I own is”Czech Baroque Music” by Musica Florea under the direction of Marek Štryncl on the Matous label and it’s a real treat. Here’s the verso with the tracklist:

A look at the list of performers shows Magdalena Kožená before she became a Big Deal as a soloist, got all glammy and started singing all that Bach. There are plenty of trumpets in Vejvanovský’s works performed on this CD and it’s true what Wikipedia says — he must have been a virtuoso. Don’t let Wikipedia’s dissing of his competence with imitative counterpoint disturb you — you’ll never notice it because Vejvanovský knows how to write a great tune. His music is as fun to listen to as Biber’s, and if you know Biber you know that’s a lot of fun, indeed.

![]()

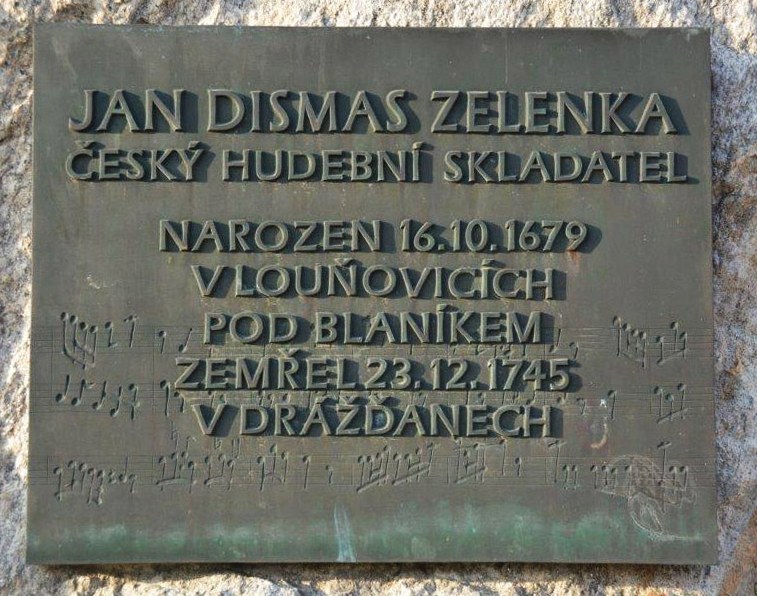

Jan Dismas Zelenka (Czech, 1679–1745)

We’ve hit a very Big Deal here. I’ll have to take a cue from Pippi Longstocking and give myself strict orders in the sternest possible voice to keep it short, otherwise this post will go on for pages and pages. I own 25 recordings of Zelenka’s music. If there were 25 more to buy, I’d get out the credit card and order them in a heartbeat. I’m a devotee of Zelenka’s music, not merely a fan. So forget about objective assessment of his oeuvre, if I didn’t love it I wouldn’t own 25 recordings and be hungry for more.

If Zelenka saw his fame today he would be gobsmacked because he was given short shrift over and over again during his lifetime. It makes for grim reading, to be honest, and I’m grateful that his works have been transmitted to us in such numbers. It would have been all too easy for them to be thrown into some corner to rot as happened to the works of so many other composers from the period. Thank goodness the archival practices of the Dresden court saved most of his manuscripts from that fate.

There are lots of resources on Zelenka available online. A good place to start is the website jdzelenka.net, which has all kinds of information on the composer including a full listing of his known works in the Zelenka Werkverzeichnis (ZWV). That page is available here. Janice B. Stockigt has written a book-length study of the composer and his works entitled Jan Dismas Zelenka: A Bohemian Musician at the Court of Dresden, available on Amazon and in part on Google Books (here). I own it and it’s excellent. If you’re into the musicological side of things it’s definitely to be recommended. The entry on Zelenka in the Český hudební slovník (= Czech Musical Dictionary) has a long list of articles on Zelenka’s work, as well, some of them in English (webpage here). If you don’t know Zelenka’s music and get the fever for it like I did you’ll easily find all the information you can handle. He’s finally hit the Big Time — a couple hundred years too late for him, poor dear, but better late than never for us.

All I’ll do here is discuss a work that has always been special to me since I first heard it over 20 years ago. It’s the sixth of the pieces in Lamentationes Jeremiae Prophetae (= The Lamentations of Jeremiah) ZWV53. A recent recording on the Supraphon label by Collegium Marianum has this information on the label’s webpage (here):

The emotive Old Testament Book of Lamentations, ascribed to the Prophet Jeremiah, has been the subject of a number of settings since the Middle Ages, with that of Jan Dismas Zelenka occupying a significant position among them. One of his first mature works composed during his time at the Dresden court, the Lamentations, alongside the Sepolcri, written for Prague (Supraphon SU 4068-2), and Responsories, are intended for Holy Week. In his Lamentations, performed as part of the liturgy of Tenebrae, the Service of Shadows, Zelenka succeeded in combining the contemplative aspect with a powerful dramatic charge. His penchant for unusual instrumentation is evident in, for instance, the final Lamentation (solo violin, bassoon and chalumeau, an instrument akin to today’s clarinet). Zelenka only set to music two lessons of the first Nocturn for each day; on the present recording, every third reading takes the form of Gregorian chant, as was most likely heard at the Dresden court. The renowned Collegium Marianum ensemble has materialised the very first complete recording of Zelenka’s Lamentations in the second millennium, one characterised by rigorous instrumentation, profound performance and remarkably conceived by three stellar soloists (Damien Guillon, Daniel Johannsen and Tomáš Král).

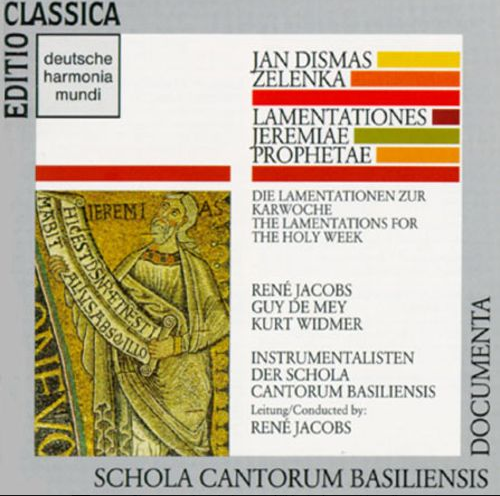

This recording of the Lamentations is fantastic but the one I heard for the first time twenty years ago was by René Jacobs with the Schola Cantorum Basiliensis on the Deutsche Harmonia Mundi label. I think it’s out of print now so probably only to be found in the resale market. I remain as attached to it now as I was 20 years ago when I bought it, despite the fact that I’ve always disliked René Jacobs’ voice, even in the performance of my all-time favorite work by Zelenka. The countertenor in the recording by Collegium Marianum, Damien Guillon, is much better. Still, I cling to the performance I first heard for the sake of its instrumental playing, which is exquisite and uses a chalumeau, an early form of clarinet. Here’s the CD cover:

As I mentioned, the piece that left me gobsmacked is No. 6 of this work — although No. 5 is a close second. The genius of No. 6 is the combination of masterful trio sonata writing with the addition of a vocal line to create a textural fabric I’ve never heard the like of in the music of any other composer. Zelenka wrote a set of six trio sonatas for two oboes, bassoon and continuo (ZWV181) that are arguably among the most astonishing instrumental compositions of the 18th century. He created a masterpiece in the Lamentationes by combining fantastic instrumental trio writing joined by a vocal line intertwining with the instruments as an equal participant. No wonder I was entranced the first time I heard it. I’m still entranced when I listen to now, more than 20 years on. If I suddenly found myself capable of writing such music I’d know immediately that I’d died and landed upstairs, not downstairs. No further proof would be needed. That’s how good this music is.

But all of Zelenka’s music is good, otherwise I wouldn’t own 25 recordings of it. With any luck the number will climb a good bit higher before I kick the bucket. My advice: RUN, don’t walk, to the nearest recording of Zelenka’s music you can find. He’s one of the best friends you’ll ever make.

![]()

So, that’s it for Slavic composers of the Baroque. What clever guys they were, these composers of such varied and wonderful music. My purpose in writing this two-part post is to broadcast their merits to the wide world in the hope that aficionados of Baroque music will include them in their collections and find enrichment from their works as I’ve done. Kudos as well to the many fine ensembles and vocalists who have recorded their music and make it possible for us to have it in our lives after centuries of neglect. For that gift we owe them an enormous debt of gratitude.