November 2018

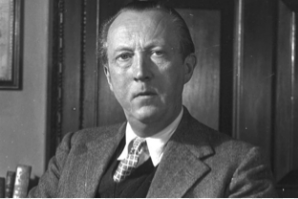

My introduction to the writing of Sacheverell Sitwell came through one of his least typical works, to wit: Southern Baroque Art: Painting, Architecture and Music in Italy and Spain in the 17th & 18th Centuries. It’s an astonishing production for a young man under the age of 25, written between 1921 and 1922 and published in 1924. Happily a Kindle version is available so I snapped it up and worked my way through it in the manner of picking one’s way through a yew hedge maze at some English stately pile.

My introduction to the writing of Sacheverell Sitwell came through one of his least typical works, to wit: Southern Baroque Art: Painting, Architecture and Music in Italy and Spain in the 17th & 18th Centuries. It’s an astonishing production for a young man under the age of 25, written between 1921 and 1922 and published in 1924. Happily a Kindle version is available so I snapped it up and worked my way through it in the manner of picking one’s way through a yew hedge maze at some English stately pile.

At the same time I bought a biography of the Sitwell trio: Facades: Edith, Osbert and Sacheverell Sitwell by John Pearson, published by Bloomsbury Reader. I was vaguely familiar with Edith’s poetry but had no clue about the lives or doings of Osbert or Sacheverell. Well, I do now. I can’t say the knowledge has made me a better person.

In point of fact, Pearson’s biography worked something of an upheaval in my understanding of the Edwardian aristocracy, about which I’d read little over the course of my delvings into things English. I knew only the broad outlines of the landed aristocracy’s history, its rapid decline after World War I and subsequent eclipse over the rest of the 20th century, culminating in the dismissal of hereditary peers from the House of Lords in 1999. The Sitwell biography puts you thick in the middle of that trajectory at the personal level while it was in full progress. I must confess I found it a bit like being at the autopsy of somebody who suffered from debilitating birth defects and wasted away in a manner that leaves one anxious to avert one’s gaze. It’s not a pretty picture.

Pearson’s book also gave me a felt sense of the English word “toff.” The Sitwells were toffs to an extreme, as can happen among aristocrats who aren’t wealthy enough to pursue their eccentricities unconcerned about social position or reputation. The Sitwells had to work hard at their upper-crustness, and work they did, with unflagging vigor worthy of a captain of industry, Edith and Osbert especially. Sacheverell took a different route by retreating early into the life of an aesthete — he was a prolific writer, to be sure, but the business of being an aesthete always came first.

Sarah Bradford wrote a biography of Sacheverell entitled Sacheverell Sitwell: Splendours and Miseries. I haven’t read it and nothing I found in Pearson’s biography of the Sitwell siblings sparks in me the desire to do so. Reading a few reviews of Bradford’s biography put me off the idea even more. Here’s what D. J. Taylor said in a review (full text here) published in The Independent in 1993 shortly after Bradford’s book came out:

IT WOULD be impossible ever to take the late Sacheverell Sitwell quite as seriously as he took himself. There are stage narcissists and there are genuine narcissists: the egotism on display in Sarah Bradford’s long and engrossing biography is of the hard sort, and ominously consistent. ‘I am, though I say it myself, about the cleverest young man of my age in the country,’ its subject wrote in his twenties to the girl who was to become his wife, adding with delicate condescension, ‘and I know you would like my companionship.’ Interviewed shortly before his death in 1988 at the age of 91, he was asked to name his most treasured possession. ‘Er, well . . . I was going to say myself.’

We have heard this note before, as it happens, heard it in Beaton’s diaries, in the letters of Brian Howard and Stephen Tennant, and in half a dozen other Twenties falderals – the shrill, high note of the aesthetes determined to masquerade as geniuses whatever the evidence to the contrary. At least it can be said in Sacheverell Sitwell’s defence that numbers of other people, principally members of his family, were keen to abet this delusion. As a poet, his sister Edith thought he was ‘one of the greatest that our race has produced in the last 150 years’. The correspondence exchanged with his brother Osbert was, until they quarrelled about money, an object lesson in mutual flattery.

The impression I gained from reading Pearson’s collective biography — which focuses much more on Edith and Osbert than on Sacheverell — seconds Taylor’s assessment of Sitwellian self-involvement. All three of the trio exhibited throughout their lives the Edwardian aristocrat’s self-referential perspective about life in general. It seems everything was a personal cause to espouse or oppose, or a call to battle for recognition to be won, but the goal was always self-promotion in the final accounting. The Sitwell agenda was ostensibly art for art’s sake. In reality the agenda was consistently art for the Sitwells’ sake. F. J. Leavis in his book New Bearings in English Poetry (1932) infamously said, ‘The Sitwells belong to the history of publicity rather than of poetry.” Sometimes it’s impossible to prettify the truth.

The youthful political involvements of both Osbert and Sacheverell make one’s eyes roll back in one’s head. Osbert was a great fan of Gabriele D’Annunzio, the Italian Futurist author and proto-fascist, an ugglesome creature if ever there was one. Osbert considered D’Annunzio a triumph of the heroic literary man over the philistine (and contemptible) mass of humanity, no doubt finding in D’Annunzio an example of the societal role he fancied for himself. We all know how that business ended: badly, very badly.

Both Sitwell boys subsequently jumped on the bandwagon of Sir Oswald Mosley’s British fascist movement until it threatened to become something more than just a fashionably outré political stance to trumpet, at which point they retreated back into their roles as aesthetes and resumed their opinion of politics as something beneath their exalted consideration. It apparently left no stain on their reputations and caused no pauses for personal reflection since toffs never really take anything seriously anyway — except social status and money, of course. That goes without saying, especially if you’re a Sitwell.

Both brothers were considered consummately charming and welcome guests at the homes of the wealthy aristocrats with whom they hobnobbed — and off whom they continually sponged. At the end of the day, charm was the only currency they had for the purchase of the upper-crust patronage and support they wanted and indeed needed. It goes without saying that they had truck primarily with others from their own class after leaving behind the more freewheeling associations of youth, so their allegiances were class-defined throughout most of their long lives.

Such was the life of a 20th century toff who clung resolutely to the patterns of the old Edwardian aristocracy. Those days are long gone and products of the old aristocracy like the Sitwells are also a thing of the past. I can’t say I think that’s a bad thing. After reading Pearson’s joint biography of the Sitwells, I’m glad my life bears no resemblance to theirs. Their lives were poisoned almost throughout their entirety by vicious squabbles about money, either about its release from the parents who controlled it or about who among the siblings had what share of it and of the family’s real estate. It makes for grim reading. I’m much better off being a plebe in the Great Unwashed.

Given that state of affairs it may provoke puzzlement that I’m writing a post about Sacheverell. The reason is quite simple: linguistically speaking his book on southern Baroque art is remarkable. It is, to be sure, an anomaly in his oeuvre. I’ve read some of his poems and have two of his travelogues, one on the Netherlands and another on Romania, which he wrote largely for income, it must be said. To make plain the vast difference between the earlier work on art and the later travelogues, compare these two paragraphs. The first citation is from the initial chapter of the art book published in 1924, the second is from the chapter on Friesland in the travelogue on the Netherlands published in 1948:

Six o’clock in the morning, and already the heat of Naples was such that it required confidence to believe in any hours of darkness. Most of the houses were still latticing the light with their barred shutters. They were skimming a soft music off the stillness, and as, one by one, the windows were thrown back, so that the shutters threw their shadow on the wall, the very strings of this fluttering music were visible, lying there as plain as anything for skilled fingers. Opposite the Church of San Domenico, in the middle of the square, there sprang forth a foaming, bubbling geyser, blowing out its lava-like fine glass. With marble and tufa it suggested equally and simultaneously a fountain playing with molten malleable stone, and a very quivering temporary trestle. The one was leaping desperately against the sky, which had lowered a cloud as cymbal for the fountain to beat upon, and the other was manifestly a hasty affair, a platform to preach from, or a pulpit high above the surging crowd. Nearer view strengthened the truth of these two guesses, as the fountain threw higher at every step you approached, and now, from close by, the saint could be seen standing, bold and balanced on his perch. The rapid alternation of these two ideas, thrown swiftly from one shuttle of the mind to the other, melted smoothly into what seemed a sure explanation. With a satisfying shock I remembered, in Marco Polo, the fountain that played with force enough to balance a metal ball three feet above its brim. So here was St. Dominic standing like a lodestar between the hot heavens and the noisy populace, his only support the thin shaking of petals of water.

Another and different country, with its own language, lies within Holland. Not a Wales or a Brittany, nothing rough, nor mountainous. Indeed, Friesland could not be more different from Brittany or Wales. It is a land of peasants and rich farmers, but we shall look in vain for the Breton calvaires and their multitude of stone carvings, or for the bragou bas, baggy breeches dating from the reign of Henri IV, wooden sabots stuffed with straw, and long hair falling on the shoulder. Indeed, we can think of no better way to begin our account of Friesland than to contrast it with a Celtic land. For Friesland is the country, particularly, of costumes, of peasants or farmers, and religious sects, something of a pastoral kingdom or land apart, another country, we would call it, in the kingdom of Cockaigne, and such in our imagination we would conceive Brittany to have been. Let us think, then, of Brittany for a few moments while we drive over the endless polders toward the dyke that takes the road from North Holland into Friesland. There is nothing much else to think of while we wait for Friesland and wonder what we shall see there.

These two excerpts are to my mind as different as chalk and cheese. In the interest of contrast I’d like to set against them an excerpt from Virginia Woolf’s A Room of One’s Own, found in the first chapter where she effuses about a garden at “Fernham” (in reality, Girton College, Cambridge):

As I have said already that it was an October day, I dare not forfeit your respect and imperil the fair name of fiction by changing the season and describing lilacs hanging over garden walls, crocuses, tulips and other flowers of spring. Fiction must stick to facts, and the truer the facts the better the fiction — so we are told. Therefore it was still autumn and the leaves were still yellow and falling, if anything, a little faster than before, because it was now evening (seven twenty-three to be precise) and a breeze (from the south-west to be exact) had risen. But for all that there was something odd at work … perhaps the words of Christina Rossetti were partly responsible for the folly of the fancy — it was nothing of course but a fancy — that the lilac was shaking its flowers over the garden walls, and the brimstone butterflies were scudding hither and thither, and the dust of the pollen was in the air. A wind blew, from what quarter I know not, but it lifted the half-grown leaves so that there was a flash of silver grey in the air. It was the time between the lights when colours undergo their intensification and purples and golds burn in window-panes like the beat of an excitable heart; when for some reason the beauty of the world revealed and yet soon to perish (here I pushed into the garden, for, unwisely, the door was left open and no beadles seemed about), the beauty of the world which is so soon to perish, has two edges, one of laughter, one of anguish, cutting the heart asunder. The gardens of Fernham lay before me in the spring twilight, wild and open, and in the long grass, sprinkled and carelessly flung, were daffodils and bluebells, not orderly perhaps at the best of times, and now wind-blown and waving as they tugged at their roots. …

That passage never fails to delight me, no matter how many times I read it. There are reasons for that delight, of course, which I’ve scarcely enumerated for myself, but the time has come to consider them and to use them as a basis for comparison with Sitwell’s astonishing string of words in his book of 1924.

There we have our stage set. Let me first critique the text from Sitwell’s book on Holland, after which you’ll find me setting his travel writing permanently aside. I bought the book in the hope it would offer an an experience of travel similar to the experience of art Sitwell provides in the book of 1924. Nothing could be further from the case. My assessment of the travel works is not charitable. Sitwell wasn’t a scholar and it shows. He’s a tourist, a toff tourist of a persuasion that can only be called alarmingly anachronistic. He loads his text with references that other posho tourists who spent some time gallavanting around Europe will easily recognize. Some of his statements leave one’s eyebrows raised in astonishment. Friesland a “kingdom of Cockaigne?” The book in which the cited text occurs was published in 1948, three years after the end of World War II, and our aristo tourist author is telling us that Friesland is like a land of fairy tales? Something doesn’t jive.

Holland had been through untold horrors during the war. There was no kingdom of Cockaigne anywhere on the ground in Europe in 1948. So I’m in a quandary about just what Friesland Sitwell is talking about. Is he describing an impression from some trip he took in the 1920’s when he was footlose and fancy-free and charging about Europe with his brother Osbert? Is he trying to conjure for our delectation a land that never really existed on the ground at all and in fact only exists in his own imagination? Is he just slapping down on the page anything that occurs to him in order to get a book ready for the publisher because he needs the money? Is he thinking of Gauguin’s paintings of 19th century Breton peasants and getting carried away into untoward similes with Friesland in the late 1940’s? Who knows. Of course one doesn’t find the cultural accoutrements of Brittany in Friesland. No sensible person would expect to find in Protestant Friesland the things one comes across in Catholic Brittany. And why, pray tell, are we on about Brittany in the first place instead of taking note of what’s in Holland on the way to Friesland? The “endless polders” are studded with architecture and have a long history. Surely there’s something to see there worth mention?

Sitwell gives the impression of being a thoroughly unreliable narrator in his role of tour guide. All the references he drops onto the page in an attempt to make himself come off as well-travelled and erudite simply show that he’s cobbling things together from whatever loose pieces he has ready to hand in his personal repertoire. We’re neither convinced about the depth of his insights nor, more’s the pity, are we particularly amused by his prowess as a raconteur. Even the language disappoints. His sentence structure is so full of hiccups that he sounds like a stuffy Anglican bishop writing a letter to the Times.

By contrast Woolf’s focus is fixed and at ease, her language is as smooth as silk and wonderfully evocative. The scene she describes leaps off the page to form living images in the mind. I don’t doubt for a moment that her text is so vivid because she herself experienced the things she describes and loved them. She renders Nature through the lens of her own perception and emotion. Sitwell seems to be writing only because that’s what he decided to do for some utilitarian reason or other. There’s no stamp of engagement with what he describes. For that reason his words lie lifeless on the page and engender no active life in the reader’s imagination.

Now let’s go back to the citation from Sitwell’s book on the southern Baroque. It’s difficult to believe it comes from the pen of the same person who wrote the travelogue on Holland. But it comes from the pen of someone who’s still young and has been leading a rather exciting life in London under the general command of sister Edith, trying to bust into the literary elite — a small group at that time, all jockeying for ascendance in the artistic firmament. His previous book was a collection of poems, The Hundred and One Harlequins, available in its entirety at archive.org here. Nick Imlah in a review (here) of Bradford’s biography of Sitwell passes along the following analysis of the poetry:

… Sachie’s infatuations – half of them with ballerinas – are characterised by his wife’s observation: ‘He cannot understand people at all . . . He sees them like pictures he has painted himself with no resemblance to reality except in outline and sometimes without even that.’ Hence he could figure his three great loves as ‘dancers at a masqued ball after fashion plates by Gavarni’, and could write to Moira Shearer: ‘I adore my bird of paradise though always surprised that you can talk.’

The ordinary stuff of humanity was likewise absent from his writing. Anthony Powell described the matter of his poems as ‘the minutiae of aesthetic sensation, rather than the poet’s relation to other people’. And the author of the prose works saw himself as ‘the Mercury or Harlequin of these pages, designed . . . to run into the world with the messages of my own feelings’. He felt prolifically enough to fill 75 volumes. The best of them, such as the early Southern Baroque Art and some of the travel books, are purposeful applications of his acute sensitivity to beauty; the worst are incoherent, monotonous, dully fantastic and forbiddingly solipsistic. ‘I write to please myself,’ he explains, ‘and I am my own best audience.’ It is the fault of too many of his works that they imagine, and so deserve, and now achieve, no other.

All the more reason to appreciate the accomplishment that Sitwell achieved in Southern Baroque Art. I preface my comments with this background information from Pearson’s biography:

… the most extraordinary and certainly the most original Sitwell book of all was Sacheverell’s — his Southern Baroque Art which was published by Grant Richards in 1924. Despite its considerable succès d’estime it was never a best-seller. (The Sitwells’ essential audience would remain a resolute minority until the publication of Osbert’s autobiography and Edith’s poems in the 1940s.) But Southern Baroque Art was a remarkably influential book from the moment it appeared. Along with Edith’s poems, which in a strange way it complemented, it soon became a sort of Bible for the Sitwellians, and put the seal upon the trio as fashion-setters in the arts. As Kenneth Clark puts it, “the Sitwells were using the Baroque to express something of their own slightly frivolous, un-English attitude to life.”

On reading Southern Baroque Art one soon sees that in southern Italy and Spain Sacheverell had suddenly discovered a fantastic and forgotten land which he could appropriate through his poet’s eye and fervent imagination. It was a land to which his father introduced him first, but during his travels with his brother he had enlarged its frontiers so that it formed a zone of magic inhabited by creatures of bright fable and elegant excess — Farinelli, the legendary castrato, the Bourbon King Ferdinand who built the last great palace of Caserta with slave labour, and even the lands of far-off Mexico, which he had never visited except in his endless reading and imagination. …

To believe in the baroque was to believe in a world before the Fall — the Fall in the Sitwells’ case being the multitudinous disasters of the nineteenth century — industrialization, the Reform Acts, total war and the decay of taste and manners in the arts … It was an elastic concept which could enfold their poetry, their taste in architecture and their love of southern Italy, while for their followers and friends a feeling for the baroque became the touchstone for a certain attitude to life, a certain species of intelligence, distinguishing the elect from the puritanical, the commonsensical, the insular, the old.

The key element, then, was authentic engagement on a large enough scale to cause the upwelling of this urgency to recount and elaborate. Sitwell’s language is the basin into which his enthusiam spills over and subsequently explodes onto the page. But just what sort of bomb goes off here?

In the title I use the simile of a confetti bomb for Sitwell’s language. I’m not just being cutesy, there’s a reason behind it. If you go back and read through the citation from the book, I think it’s easy to see that his linguistic strategy is indeed rather like a confetti bomb. When I first read the passage I was impressed by the bravura of the presentation but had no real idea what Sitwell was on about. I only realized that I was before an astonishing linguistic performance and that the medium was likely the greater part of the message. The text reads in fact like a prose poem rather than like the discursive — indeed dully discursive — text of the later work on Holland. Clearly the authorial intent is not to comply with the conventions of travel literature, however intelligent, accomplished or evocative it may on occasion be. Sitwell is doing something quite different here: writing a travel book like a prose poem. He uses language to scatter images and concepts across one’s field of awareness rather than to focus on particular objects in linear fashion as one would in a traditional travel account. In other words, he explodes a confetti bomb and starts a word party. What a great idea.

I was unprepared for that linguistic approach when I first started reading the book. After going through a couple pages I stopped because I could barely follow the meaning, although the ride was thrilling before I hit the brakes. The only other author who has produced a similar experience for me is Theodor Adorno, obviously for very different reasons. Adorno’s prose is like matter from a neutron star, you start a page and find that his authorial gravity has suddenly sucked all the space out of your atoms and collapsed your electrons into your protons, leaving you to plow through a density that ordinary mortals are ill-equipped to handle. Adorno’s prose has to be excavated for the reserve of meaning underneath it, but the reserve is there if you drill deep enough. He always delivers.

Sitwell’s prose in Southern Baroque Art is by contrast entirely literary in its effect and that effect is indeed the major message as my initial impression suggested. It’s language that sports about like puppies enjoying a good romp. The poetical phrases make that agenda quite clear: “latticing the light,” “skimming a soft music off the stillness,” “lowered a cloud as a cymbal for the fountain to beat upon.” Those phrases and their like throughout the book could easily come from one of Sitwell’s poems when he was consciously a Harlequin doing what comes naturally to such a stylized creature. When his prose is compared to Woolf’s in her essay, one sees immediately that Sitwell’s production is a performance to achieve a calculated effect. Woolf’s text is a communication. In that difference lies the great gap between the sense we receive of Sitwell and of Woolf as authorial voices. Sitwell is an actor on a stage. Woolf sits beside us on the sofa and talks of an experience she wants us to share with her, perhaps she moves to the edge of her seat as emotion flushes through her. Either approach has its own literary legitimacy, but of the two Woolf’s approach makes her a companion of one’s days over long years. Sitwell’s approach engages the attention for while, enjoyably so, but one doesn’t live in the theater. One watches for a while then goes home. Sitwell is nowhere to be found at home. Sitwell performs and demands our admiration but he doesn’t communicate. We’re of no importance to him save as an audience for his performance. An invitation to tea from the likes of us would doubtless be considered impertinence since, after all, we’re not toffs and offer no interest at all as objects off which to sponge financially. We are to applaud and then disappear.

The section of the first chapter on Caserta, the Brobdingnagian Baroque palace built by the Bourbons, gives occasion for an orgy of mythologizing. The past overlays any present from the 20th century so completely that one is transported into a fantasy. The text reads like a narrative giving life to a Watteau painting, so much so that the images springing to mind are difficult to dissociate from Watteau after one makes that mental connection. Does it bring to the reader a clearer sense of Caserta as a piece of architecture, of its history, of the context in which it came to be? Nothing of the sort. It’s a canvas on which Sitwell paints vignettes of the time before the Fall. It makes for pleasant and lively reading, but it has little to do with reality. If what you’re writing is a prose poem, however, reality needn’t figure too greatly in the end result. Poetic license, etc. etc.

… By the time it was dark and the Royal family were formally to enter the garden, this immense affair was so crowded and so moving with colour as to give the air of being bedded out, for the occasion, with numberless and varied flowers. Enough lights glittered for a galaxy of stars. Theatre art had been called in, and some very satisfactory platforms and gangways were in temporary existence. Till the moon rose it was very dark, but the cries of fruit and drink sellers acted like so many signboards giving the name of each bed of flowers and showing the gardener his duties. Occasionally a murmur that their automaton had left his booth blew among the crowd, passing from lip to lip like a wind among dry leaves. …

A flight of rockets which shot up into the air and then dangled below a trellis of cloud, like clusters of grapes, was an abrupt signal to all the onlookers that the ceremony had begun. The King’s state descent of the staircase was arranged and coaxed with a loving care. Both sides of the stair were lined with halberdiers, and the retinue in front and behind made it all but impossible for him to leave the track. But the precautions imparted an air of danger to the proceeding, and at the same time magnified the condescension of his act. …

From thence we head into a scene of Rococo merrymaking which, based on its description, seems for all the world to be the Embarcation for Cythera. Oh the good old days, where have they gone …

The interstices in the book between art and history are so large that it’s a good thing Sitwell fills them in amusingly with what can only be called historical fiction. Trenchant insight into the works described in the book is not forthcoming. It does well to remember that in the fullest sense of the word Sitwell was an amateur. Consequently, he brings forth his parade of vignettes and impressions simply as a tourist with an exceptionally vivid imagination. That the book is justifiable as something publishable under its title has everything to do with the language and very little to do with the actual content, truth be told. Without the confetti bomb of the language into the bargain, we’d have on our hands an art book that delivers not a bang, but a whimper.

Does Sitwell manage to keep up the performance straight through the work to the very end? Well, not exactly. The elaborate fictive framework remains in place but the language trails off from its apex in the first chapter to a considerably more travelogue-like tone. We’re treated, however, not to travelogue but to more historical fiction. At the end of the book we come to the story of Farinelli, the famous Italian castrato, during his years in Spain in service to the King:

He began with that same song he had conquered with in Vienna. The crescendo, like a terrifying hurricane, made the King tremble. But Farinelli sank his voice back to a whisper, as if to show that every mood was in his control and that he could attract affection as well as command obedience. The King sat spellbound in front of his glass, unable to believe that his singing came from an invisible source, for there were no sign of its origin that he coud see collected in his glass from the widespreading area of the garden. Then some peculiar quality in the way the sound reached his ears, suggested that the voice was somewhere near, perhaps hidden directly underneath the window, and too steeply down to be reflected. So he got up and walked cautiously to the pane.

It reads as though the book were an historical novel rather than a study of Baroque art. One may cavil at the inability of the author to hold a focus, but it’s apparent to me that he’s doing exactly what he really set out to do: he’s being aesthetic. He’s flaunting his membership in the club of (upper-class) aesthetes who know how to appreciate such fine things and have the money to dash about looking at them, unlike the philistine mass who do tiresome, disagreeable things like mine coal, raise crops, cook meals, wash laundry, etc. etc. — all of which, it goes without saying, is beneath the consideration of a toff. That’s perfectly self-evident if you’re a Sitwell. As Dame Edith said on more than one occasion, “I am a Plantagenet!” Fat lot of good royal lineage did her when it came time to pay the backtaxes she’d neglected to settle over the years, but yes, she was in some measure a Plantagenet …

It’s not my intention to give a general valuation of Sitwell’s oeuvre, if for no other reason than the dread I feel at the idea of having to read it all LOL. I’m content to give Sacheverell two thumbs up for a job well done on this one book. It’s fascinating, pleasantly surprising and at this point in history gives off the faint and agreeable fragrance of a vanished past, as would a handkerchief doused with scent that was left in some Edwardian dame’s trousseau and found by her descendants.

Given the degree to which our language has lost its dimensionality in these late days and how it now struggles to convey anything aesthetic, linguistic feats such as the one Sitwell performs in Southern Baroque Art are worth their weight in gold. On that basis alone I think his book deserves to remain current among us. We need all the help we can get.