April 2020

Winston-Salem is a very pleasant place. It’s very leafy and green and gives the impression of being fairly well-heeled. It does well to remember that North Carolina was one of the 13 original colonies with all the historical baggage that entails. There are standards to live up to when you’re one of the original 13, after all. You have to know your way around Federalist architecture, you have to be able to handle red brick aesthetically and you have to have a penchant for painting your shutters the right color. Black is preferable, it looks better against red brick.

Winston-Salem is a very pleasant place. It’s very leafy and green and gives the impression of being fairly well-heeled. It does well to remember that North Carolina was one of the 13 original colonies with all the historical baggage that entails. There are standards to live up to when you’re one of the original 13, after all. You have to know your way around Federalist architecture, you have to be able to handle red brick aesthetically and you have to have a penchant for painting your shutters the right color. Black is preferable, it looks better against red brick.

Winston-Salem has got all that down pat. There’s neo-Federalist architecture in any direction you care to point, the brick is as red as you please and the lawns are impeccable. The locals have the Moravians in their history in addition to a major captain of industry in the person of R.J. Reynolds of tobacco fame (or infamy, depending on your point of view). Old Salem is the Moravian ne plus ultra in the United States but it came after the establishment of Bethabara on the outskirts of Winston-Salem, where the first Moravian settlers from Pennsylvania set up shop. This post is about that first settlement, viewable in Historic Bethabara Park. To get things rolling here’s a schematic:

It’s a small area, in point of fact and the ensemble of buildings is quite modest in size — the Gemeinhaus, the Log House, the Barn and the Distillery, to tick off the main ones. The info supplied by the site’s Wikipedia page (here) makes the reason for this paucity perfectly clear:

Bethabara (from the Hebrew, meaning “House of Passage” and pronounced beth-ab-bra, the name of the traditional site of the Baptism of Jesus Christ) was a village located in what is now Forsyth County, North Carolina. It was the site where twelve men from the Moravian Church first settled in 1753 in an abandoned cabin in the 100,000-acre (400 km2) tract of land the church had purchased from Lord Granville and dubbed Wachovia.

Its early settlers were noted for advanced agricultural practices, especially their medicine Garden, which produced over fifty kinds of herbs.

Bethabara was never meant to be a permanent settlement. It was intended to house the Moravians until a more suitable location for a central village could be found. Just six months after arriving in Wachovia, the Seven Years War (known as the French and Indian War in America) began in western Pennsylvania. The violence quickly spread to southwestern Virginia and western North Carolina. Bethabara hosted a large number of refugees until 1761. The establishment of a central town was delayed for thirteen years because of the growing Moravian population and hundreds of refugees.

Once it was felt safe to do so in 1766, the central town, Salem was begun. Many of the buildings in Bethabara were dismantled, and used for the new structures in Salem. As the houses were taken down, the small rootcellars were pushed in and filled.

With Salem completed in 1771, the official seat of government was transferred from Bethabara to Salem. Only a few residents remained behind. Bethabara became a farming community which supplied food to the other Moravians towns in Wachovia.

Anyone who’s visited Old Salem will recognize immediately the provisional feel of Bethabara. It feels like an outpost rather than a town because that’s exactly what it was. Being familiar with Old Salem as I am, I can easily trace the developmental trajectory from Bethabara to Salem and appreciate both places for what each represents of Moravian history, which is admirable in both its manifestations. The Moravians were as like Quakers as any religious group in America was and their settlements have an air of peace and orderliness about them. So despite the small size I find Bethabara a lovely place and I’m glad I had a visit. I haven’t yet revisited Old Salem after long decades away from the area, so I’m looking forward to seeing it again with the sights of Bethabara in mind this go-round.

Let’s start at the Distillery and work our way over to the gardens. Here’s the blurb on the building:

Without wishing to cast any aspersions I must confess that it’s rather unprepossessing as houses go — there are much posher ones in the neighborhood just down the street. But it’s situated well and has lovely grounds, as the pics show:

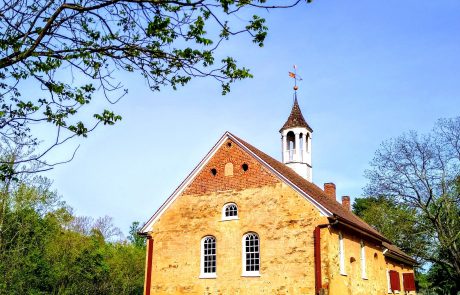

The jewel in the crown of Bethabara is, of course, the Gemeinhaus — in English, “Common House.” It’s the church and parsonage rolled into one and certainly formed the beating heart of the community. The construction date for the present structure is 1788, which is post-Salem (1771) but who’s counting? Here’s the blurb:

It reminds me of some of the buildings in Old Salem and has that lovely simplicity and solidity of Moravian things. There’s always some ornament added and a fine sense of proportion in the architectural design. Here are the pics:

Right next to the Gemeinhaus is the Palisade. Given that most of the buildings of the settlement are gone and only some stone foundations remain as remembrances, I suppose it was a good idea to reconstruct the Palisade, and it’s a cheap date because it’s basically just a big wooden fence. It brings the issue of warfare to the forefront, unfortunately, which misfortune thankfully never visited the settlement, but conflict between the invaders (us white folks) and the natives went on a good while. I can’t imagine the Moravians wanted anything to do with it. They doubtless spent a lot of time praying that people would lay aside the work of Satan and sow peace rather than hatred. It sounds like the sort of the thing they’d do, just as they’d done among themselves only a few decades earlier (info here):

In 1722, a small group of Bohemian Brethren (the “Hidden Seed”) who had been living in northern Moravia as an illegal underground remnant surviving in Catholic setting of the Habsburg Empire for nearly 100 years, arrived at the Berthelsdorf estate of Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf, a nobleman who had been brought up in the traditions of LutheranPietism. Out of a personal commitment to helping the poor and needy, he agreed to a request from their leader (Christian David, an itinerant carpenter) that they be allowed to settle on his lands in Upper Lusatia, which is in present-day Saxony in the eastern part of modern-day Germany. The Margraviates of Upper and Lower Lusatia were governed in personal union by the Saxon rulers and enjoyed great autonomy, especially in religious questions.

The refugees established a new village called Herrnhut, about 2 miles (3 km) from Berthelsdorf. The town initially grew steadily, but major religious disagreements emerged and by 1727 the community was divided into factions. Count Zinzendorf worked to bring about unity in the town and the Brotherly Agreement was adopted by the community on 12 May 1727. This is considered the beginning of the renewal. Then, on 13 August 1727 the community underwent a dramatic transformation when the inhabitants of Herrnhut “learned to love one another”, following an experience that they attributed to a visitation of the Holy Spirit, similar to that recorded in the Bible on the day of Pentecost.

Herrnhut grew rapidly following this transforming revival and became the centre of a major movement for Christian renewal and mission during the 18th century. The episcopalordination of the Ancient Unitas Fratrum was transferred in 1735 to the Renewed Unitas Fratrum by the Unity’s two surviving bishops, Daniel Ernst Jablonski and Christian Sitkovius. The carpenter David Nitschmann and, later, Count von Zinzendorf, were the first two bishops of the Renewed Unity.

Such sensible people, no wonder being around their things leaves you feeling relaxed and edified. So we should interpret the Palisade as a piece of protective foresight, nothing more. There are no slits for gun barrels or perches for pots of boiling oil. I imagine the posts used to make it eventually found their way into the woodshop or into the stove. That’s my guess based on the general tenor of the proceedings. Anyhoo, here are the pics:

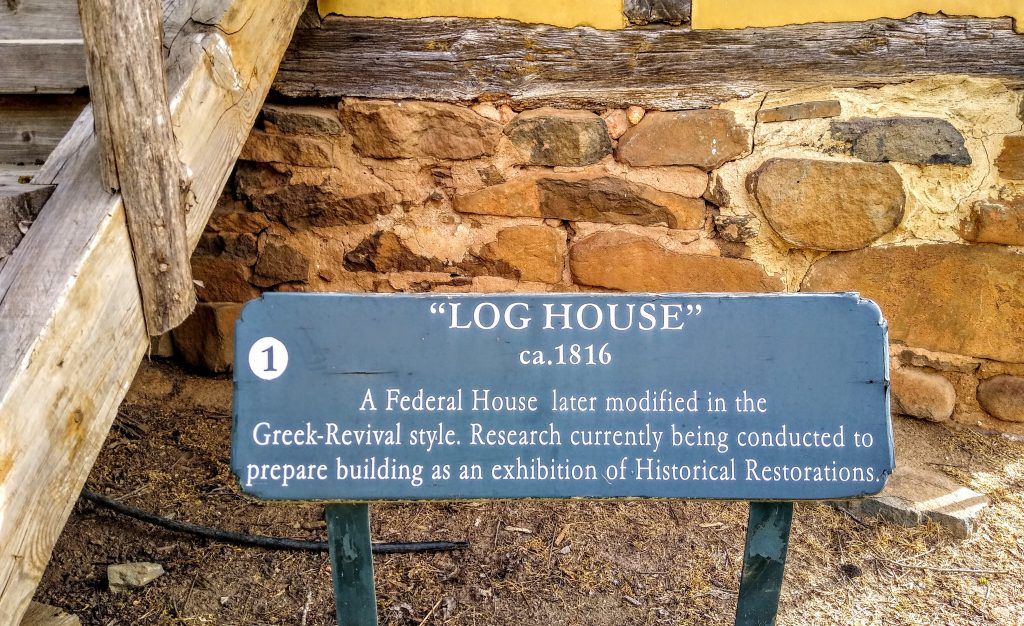

Just across the street from the Palisade is the Log House. The name is perfectly descriptive, don’t you find? No need for elaboration of the basic item. We all know what a log house is. That fact leaves me at great pains to explain the text of the blurb:

What? WHAT?? Are you SERIOUS??? All y’all need to read up on your styles, baby doll, ’cause this place ain’t the one or ‘tother. Federalist architecture is a variant of the Georgian architecture all the rage in the England of the period — think of Bath, which is about as Georgian as you can get. Greek Revival was all the rage among the builders of Southern mansions on plantations, so for that bit think of Scarlett O’Hara’s digs in Gone With the Wind. Just to set a baseline, here are examples of Federalist and Greek Revival architecture in town halls from Massachusetts and Connecticut, two other colonies of the original 13:

If I’ve said it once I’ve said it a million times: don’t go off your meds. You can see what happens when you do and it’s not a pleasant sight.

With that small stylistic detail handled, let’s proceed to the pics. Again, I have no idea what the interior of the building looks like, but I can easily forego that knowledge and content myself with the exterior. It has a certain rustic charm, that much must be granted it, but you’ll not see its like in Old Salem. Things had progressed well beyond that point by the time Salem went up. Here are the pics:

The last bit to occupy our attention is the gardens. One can only suspect based on the evidence that presents itself that they have been parkified and thus rendered more ornamental than they were originally. Moravians were excellent agriculturalists and I’m sure they had things geared for production, not for display. Personally I’d be delighted to see things as they were when the place was a going concern, I love a proper kitchen garden. As things stand there are some herbs and a few flowers, and a quaint gazebo as an ornament to the space. The wooden fences are pleasing to the eye — they seem to be the go-to for both historic gardens and for Civil War battlefields, although the relationship between those two things remains opaque to my understanding. That’s probably just as well, so let’s get on with the pics:

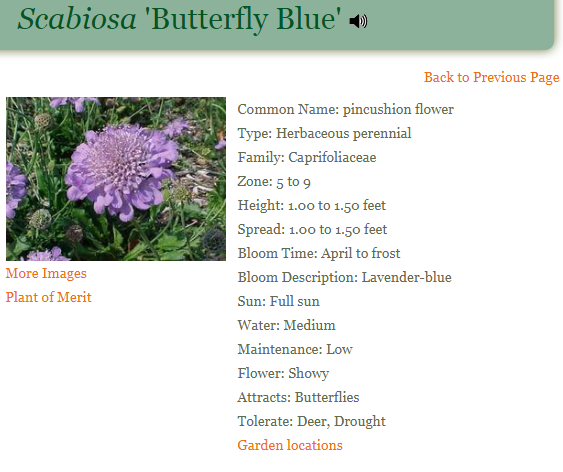

The honeysuckle climbing up the trellis is a jaunty red thing, a color that I’m not used to seeing in honeysuckle. Wild honeysuckle (always white, never red) is common in North Carolina. In some places it grows so thick the air is perfumed with it for a few weeks of the early summer. I have a memory of driving down a highway near Yanceyville, NC with the windows open and the delicious fragrance of honeysuckle flooding through the car. Fabulous! The Scabiosa (dreadful name, “pincushion plant” is a much friendlier vernacular) in the last pic holds forth in a small butterfly garden and is eminently well placed, as this info on the variety from the Missouri Botanical Garden makes clear:

It blends beauty and utility in a way I think would have appealed greatly to the Moravians. Thumbs up to it on both counts.

I think I missed one of the buildings in my perambulations — the Potter’s House. I excuse myself on the basis of the structure being so humdrum that it didn’t stand out to my eye as I wandered. I was actually far more interested in appreciating some wild roses of the Southern variety — so different from the wild roses in my neck of the woods. In the South they are petite things, and white, not pink, with no discernible scent. The species name is, I believe, Rosa blanda, which seems a bit judgemental IMHO. The vernacular, “prairie rose,” is equally unsatisfying since I’ve seen it grow in all sorts of terrain but never on a prairie. So I’m sticking with “Southern wild rose” despite its being a neologism. In my neck of the woods it’s Rosa nutkana that rules the wild rose roost and the scent of it is heady enough to induce a swoon if you get a strong drift of it. But the demure nature of the Southern wild rose is lovely and I was delighted to find some blooming near the Distillery. What a perfect finish for my tour of Historic Bethabara, a place I’d recommend wholeheartedly to anybody visiting Winston-Salem. Don’t let Old Salem get all the attention, Bethabara was there first and deserves a good look.