June 2019

When we think of German composers the first thought that comes to mind is rarely about pleasure for the sake of pleasure itself. We expect them to scale some sort of heights, be it those of contrapuntal rigor (as in J.S. You Know Who), sprawling mythos (we’re lookin’ at you, Herr Wagner) or archetypical heroism (e.g., Beethoven on the barricades shaking his fist and yelling about something or other). German musical history does have its songbirds, however. They get little attention for some reason that mystifies me — the quality and quantity of their music should by right command a place front and center in our awareness of German musical heritage. But canon formation works many disfigurations on historical reality in both music and literature. This post is my attempt to provide pushback against that structural neglect of wonderful composers who’ve given me enormous delight over the course of my lifetime. They form an important link between German musical practice and European cultural development in the 18th century. We should sing their praises as artfully as they spun their melodies. And what melodies! That’s the prize on which we set our eyes: melodies galore. Let’s have a closer look.

When we think of German composers the first thought that comes to mind is rarely about pleasure for the sake of pleasure itself. We expect them to scale some sort of heights, be it those of contrapuntal rigor (as in J.S. You Know Who), sprawling mythos (we’re lookin’ at you, Herr Wagner) or archetypical heroism (e.g., Beethoven on the barricades shaking his fist and yelling about something or other). German musical history does have its songbirds, however. They get little attention for some reason that mystifies me — the quality and quantity of their music should by right command a place front and center in our awareness of German musical heritage. But canon formation works many disfigurations on historical reality in both music and literature. This post is my attempt to provide pushback against that structural neglect of wonderful composers who’ve given me enormous delight over the course of my lifetime. They form an important link between German musical practice and European cultural development in the 18th century. We should sing their praises as artfully as they spun their melodies. And what melodies! That’s the prize on which we set our eyes: melodies galore. Let’s have a closer look.

The canon excludes by imposing silence on those who haven’t been placed within its ranks. Neglect and forgetfulness are its chief strategic weapons against the astonishing breadth and depth of musical life as it actually played out in the historical record. The historical period and the composers I’m talking about here don’t have anywhere near the same amount of scholarly material written about them you’ll find for one of the canonical composers. Given that fact, I’ll present my own snapshot based on what I’ve gleaned from the musicological literature. When I talk about the composers individually, however, the opinions are purely personal. These guys are good friends of mine. I want to sing their praises, not prove an academic point. My motivation is the hope that more listeners will find their delight where I find mine as I listen to this wonderful body of music.

Technical Terms: “Emfindsamkeit” and “Galanter Stil”

Let’s get the history stuff straight to start with. We’re talking about a stylistic shift from the High Baroque of Bach and Handel and Telemann to the Classical style of Mozart and Haydn and Beethoven. History is never as clear-cut as we like to make it in our history books, but no matter. We only need to understand the broad outlines of the stylistic changes that occurred in the music of the second half of the 18th century. Let’s use opera as our example since it provides a clear example for our understanding.

If you watch an opera from the High Baroque staged with an eye to period authenticity, it will immediately strike you that people behave very differently on stage than they do in the Romantic opera from the 19th century we know best. We’re used to seeing people carry on like it’s a Mexican soap opera. Things go over the edge emotionally all the time. The characters are continually screaming, sobbing, shrieking or emoting in some other fashion you’d expect to see in a group of people getting seriously worked up about something.

In a Baroque opera people behave quite differently. Instead of overwrought individuals running about the stage you find rhetorical representations or embodiments of a particular nature or quality moving in measured patterns and declaiming their arias. In the libretti you find among the dramatis personae names like “Beauty,” or “Wisdom” or “Time.” Even if a character has a particular name — nine times out of ten drawn from classical mythology — that character is fundamentally allegorical, not the representation of a specific human individual full of feelings and quirks and perhaps an occasional tendency to personal expression of too vigorous a nature.

This allegorical stance has its structural elements in the music, as well. The musical forms of the High Baroque are shot through with a symbolic approach to reality. That stance finds expression in abstractions that take the form of things like counterpoint. Baroque composers thought it reflective of the music of the spheres, no doubt — something like Aristotle set to music, if you will. For all of us who love Baroque music it’s easy to name reams of favorite compositions from this tradition. All the big names were part of it. Certainly there’s emotion expressed in their music but it’s stylized, not the raw, over-the-top kind we find in works from 19th century operatic literature. In the opera of the High Baroque you might find goddesses getting riled up about one thing or another, but you’ll never see hookers kick the bucket while singing about how sorry they are they messed everything up. Perish the thought!

While the High Baroque was in its middle to late phases another tradition sprang up and began to steal the show, to the point that composers like Bach felt even during their lifetimes the effects of changing fashions. The new tradition got its start in Italy — like so much else in the musical firmament — and came to Germany through composers who adopted the new style and spread it about in their own neck of the woods. One of the most famous of these trendsetters was Johann Adolph Hasse (1699-1783, info here). Born in Hamburg into a line of church organists, Hasse went to Naples early in his career and ended up making a big splash there. After several years in Italy he won the appointment as Kapellmeister to the court in Dresden where he received a huge salary and was absent much of the time attending to his ongoing activities in Italy. In his day he was considered one of the top opera composers in all of Europe. We don’t hear much about him these days and general opinion of his music is certainly well below the pinnacles on which we perch J.S. You Know Who. How ironic that Bach toward the end of his life was considered an old fuddy-duddy compared to Hasse. At the time of his death Bach’s style of writing was already considered long in the tooth. Hasse was the musical Mazzerati of the day. Bach was the Chevy station wagon parked in the suburban garage in Leipzig.

A few variants of this new style emerged in Germany. One was centered in Berlin and included one of Bach’s sons, C.P.E. Bach. He represents what’s called Empfindsamkeit (= Sensitivity), a musical aesthetic characterized by what can best be called shock value. C.P.E. Bach’s style is highly idiomatic and constantly fakes you out. Think you can guess what’s coming next like you do with High Baroque music? Think again, there’s a curve ball coming from old C.P.E., for whom the expected is anathema. Some of the pieces he wrote might lead one to suspect that he went off his meds when he should have stayed on them. The stylistic agenda of his music is consonant with the galant style, however, because it favors emotional expressivity over slavery to the musical conventions that dominated the High Baroque. He’s by far the quirkiest of the composers in the new style. Others took a very different and smoother approach.

If you’ve ever listened to German folksongs you’ll not need me to tell you that some of them have very beautiful melodies that stick in your mind. They reveal the native German gift for melody. Precisely that gift is engaged in a second strain of the galant style that happens to be my favorite. It’s full of lovely melodies that cling to your memory and keep you humming under your breath. The compositional techniques involved in this strain move radically toward monody and away from contrapuntal structure, with a trajectory heading straight for the aesthetics of the Classical period as it shows itself in the Mannheim School with such composers as Stamitz. The fact that the melodic strain of the galant style was going on during the same years that Bach was doing his High Baroque thing in Leipzig just shows how jumbled together all these phenomena were in historical fact. They can’t realistically be plotted out in linear fashion on a timeline as our music history text are wont to do.

But no matter, we’re not historians of music, we’re just folks who like a good tune and want some nice stuff to listen to. We have in that agenda great good fortune with the composers of the period under consideration. It’s not about following retrograde canons at the fifth or straining our grey matter to take in all at once the contrapuntal weavings of four or five independent voices. We’re handed a pretty melody on a plate and told, “Enjoy!” What’s not to like about that?

The Guys With the Goods

It’s time now to have a look at some of the individual composers of this aesthetic thread. As usual I’m drawing on composers whose works I have in my own collection of recordings, not just names pulled out of an encyclopedia. I won’t worry about holding to a strict chronology, either — the example of the historical record itself is enough to grant me that liberty. As is my wont I’ll just plop the names down as I come across them in my list of recordings and let the gods of alphabetization take the hindmost.

![]()

Johann Philipp Kirnberger (1721-1783)

First of all, let me state for the record that Kirnberger was a student of J.S. You Know Who. I say that in the interest of transparency — it shows that despite Kirnberger’s associations I recognize his merits on their own account and accord him the highest respect despite any unease about his history. Let it never be said that I am a person of narrow mind in such matters. As a Baroque flautist I’ve also engaged him up close and personal because he wrote flute sonatas I find really lovely and have played in concert.

Another reason I like Kirnberger is that he was Slav-friendly. He had substantive musical connections with Poland and collected Polish dance tunes, as we find out in his Wikipedia page (here). He landed a job as violinist at the court of Frederick the Great and eventually became director of music for Anna Amalia, the king’s sister who lived in Berlin and devoted much of her time to music.

Kirnberger isn’t very well known these days despite having been a very good composer. Your ears will tell you that, but you can also rely on the opinion of Kirnberger’s contemporaries, who accorded him plenty of kudos during his lifetime. He was also a theorist of note and for those of us into organ stuff the name is familiar because of his writing on temperaments (tunings) that have to do with the move toward equal temperament during his historical period. You might remember that his teacher, J.S. You Know Who, wrote The Well-Tempered Klavier in every key under the sun to support that same idea.

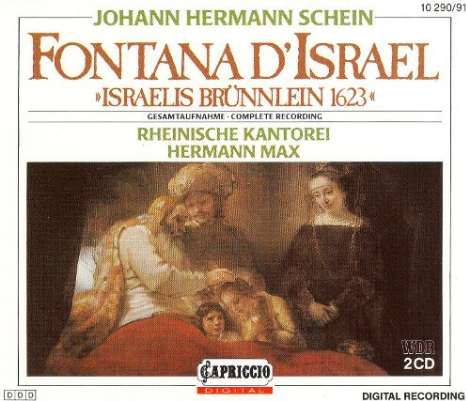

As for recordings, they’re thin on the ground. I came to Kirnberger as a performer rather than a listener so it distresses me that so few of his works have been recorded. The clearest evidence in support of my inclusion of him in this list is a duet from his cantata “Erbarm dich, unser Gott” which figures as an outlier on Disc 2 of a recording of Hermann Schein’s “Fontana d’Israel” directed by Hermann Max. It appears together with two works by C.P.E. Bach and works by Johann Adam Hiller and Johann Friderich Dolles, both of whom fully deserve to be on this list but have so little music available it degenerates quickly into an exercise in futility. Here’s the recto of the CD in question:

About halfway through Kirnberger’s cantata things go from dark, brooding chromaticism of a decidedly Empfindsamkeit character to pure sunshine. A Mozartean melody suddenly pierces the dark clouds and two sopranos warble sweetly about humans being born weak and sinful (‘Schwach und sündig ist der Mensch geboren”). I agree that it hardly seems a thought particularly well suited to lighten the mood, but the melody is all sweetness and light, trust me. That melody alone is enough to land Kirnberger in this list with two thumbs up.

The most available recording is of some of Kirnberger’s sonatas for flute and basso continuo. The recording I own, done by the inimitable Baroque flautist Frank Theuns, is long in the tooth and no longer available on Amazon, but you’re in luck: it’s available in its entirety on YouTube here. Enjoy!

![]()

Johann Ludwig Krebs (1713-1780)

Guess what — we have on our hands here another student of J.S. You Know Who. Even Krebs’s dad studied with J.S.B., so it ran in the family. Here’s the skinny from the Wikipedia page on Krebs (here):

Krebs studied with Johann Sebastian Bach on the organ. Bach (who had also instructed Krebs’s father) held Krebs in high standing. From a technical standpoint, Krebs was unrivaled next to Bach in his organ proficiency. However, Krebs found it difficult to obtain a patron or a cathedral post. His Baroque style was being supplanted by the newer galant music style and the classical music era.

Krebs took a small post in Zwickau, and in 1755 (five years after the death of Bach, which is normally referred to as the end of the Baroque period) he was appointed court organist of Saxe-Gotha-Altenburg under Prince Friedrich. Krebs had seven children and struggled to feed his family. Despite never holding a court composer post, and never being commissioned for a work, Krebs was able to compose a significant collection of works, though few were published until the 1900s.

It appears Krebs picked up the notion of excessive reproduction along with the organ lessons, but at least he stopped well short of the double digits Old Bach reached before old age put a stop to him … Anyhoo, Krebs wrote a lot of music and in the Baroque revival he has fared fairly well. As a result, we have many recordings of his works in the marketplace. I own the complete organ works performed by Beatrice-Maria Weinberger on various historic German organs from abbeys in the south of the country (e.g. Neresheim, Ochsenhausen, and Weißenau) purveyed to eager listeners over the considerable span of seven CDs. There are many delights waiting to be discovered in that body of work. Believe it or not, there’s even more than one recording of the complete organ works on the market now, so you can choose the one you want.

The pieces that qualify Krebs squarely for inclusion in this list, however, are chamber works for flute and harpsichord, pieces some of which I’ve also played in concert. They’re delighful and as tuneful as the day is long. There are a couple recordings available on Amazon and you’ll also find some examples on YouTube. This is Krebs throwing himself headlong into the galant style and leaving behind the contrapuntal tradition he learned from his teacher. His Polonaises in the flute sonatas are especially jaunty. Have a listen — you’ll soon find yourself humming along.

![]()

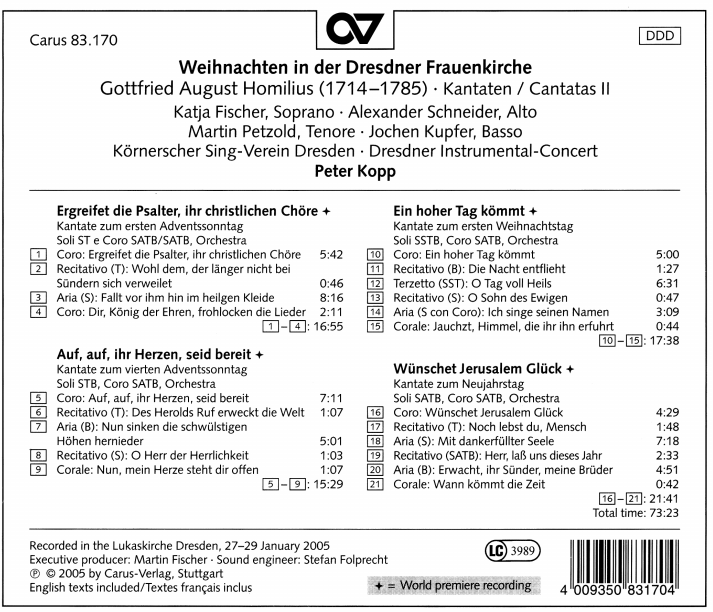

Gottfried August Homilius (1714-1785)

Guess what … need I continue the sentence? Yep, you guessed it: another student of J.S. B. … Oh well, never mind. It was a small world in Saxony in the 18th century so we can’t very well cavil at people being in each other’s pockets, can we. I assure you that when you hear Homilius’ music the last thing you’ll think of is J.S. You Know Who, because Homilius is one of the true songbirds of the period. He writes ravishing melodies with the ease of a Mozart — just put a pen in his hand and out they flow unbidden, so it seems.

Throughout his professional life Homilius held key appointments in Dresden, including posts at the Frauenkirche and the Kreuzkirche. So he was a Big Deal in his day, no question about that. He’s done very well by the Baroque revival of the past 20 years and has found a couple champions who’ve given us wonderful performances of his church music. There’s even an Amazon page for Homilius here. You’ll find plenty to listen to on YouTube, as well. I own seven recordings of works by Homilius, all of them music I’d be very sad indeed to lose or never to have known. He’s that good.

One of the pieces that left me gobsmacked when I first heard it is the Terzetto from the cantata “Ein hoher Tag kömmt” from the two-volume recording of cantatas for Christmas done by Peter Kopp. Here’s the verso — it’s still available on Amazon btw:

Structurally speaking the piece is in da capo aria form, with the terzetto being the A section and the B sections given over to each member of the vocal trio (two sopranos and a tenor) as soloist. Such a clever guy, it works a treat. The melodies are so fluid and pleasing and the orchestral accompaniment flows so smoothly around the voices that it’s immedately clear you’re in the presence of somebody who’s absolutely top-drawer. All his music is like that, I’ve never heard anything he wrote that made me think, “Hmm, must have been an off day …” Fabulous stuff, chase it down and have a listen, you’ll be a better person for it. And a happier one, trust me. 🙂

![]()

Johann Gottlieb Graun (1703-1771)

Finally! Somebody who didn’t study in Leipzig with You Know Who! Yaay!! Graun studied with somebody named Johann Georg Pisendel who’s a Baroque powerhouse in the shadows, much like Graun himself. After study with Pisendel Graun went to Italy and studied with Giuseppe Tartini (of Devil’s Trill fame), which is definitely an ooh la la thing to do if you want to be a hotshot composer. The only problem with that plan was that Graun had a brother, Carl Heinrich, who became a famous opera composer in Berlin and overshadowed his instrumentalist brother something fierce. I don’t know if it ever came to words between them because of it, but Carl Heinrich certainly came out on top of the fame and riches heap. It’s a pity really, since Johann Gottlieb was one of the best instrumental composers of his day, bar none. Here’s the skinny from his Wikipedia page (here):

Graun’s compositions were highly respected, and continued to be performed after his death: “The concert-master, John Gottlib Graun, brother to the opera-composer, his admirers say, ‘was one of the greatest performers on the violin of his time, and most assuredly, a composer of the first rank’,” wrote Charles Burney. He was primarily known for his instrumental works, though he also wrote vocal music and operas. He wrote a large number of violin concertos, trio sonatas, and solo sonatas for violin with cembalo, as well as two string quartets —- among the earliest attempts in this genre. He also wrote many concertos for viola da gamba, which were very virtuosic, and were played by Ludwig Christian Hesse, considered the leading gambist of the time.

Despite the popularity of his works, Graun was not free from criticism. Burney noted that some critics complained that, “In his concertos and church music … the length of each movement is more immoderate than Christian patience can endure.”

To Burney’s comment about length I reply, “Where’s the frigging fire? Get out your phone and do Angry Birds if you must, just keep quiet and let us listen to the music!” Goodness sake. Or maybe the problem is that I’m not a Christian so I have more patience than I should. In any case, if you follow the thematic development in Graun’s music you’ll be amazed, amazed I say, at his inventiveness. He’s got the melodies, yes indeed, but how he spins them out of one another and weaves them together will leave you feeling like you’re watching one of those light shows they put on under Niagara Falls.

There aren’t many recordings of Graun’s music available — the ones I own and love are not in the marketplace anymore. But if you head over to YouTube you’l find plenty to get you set up for a good listen. I’d suggest two things in particular: (1) the trio sonata for flute, viola and basso continue in F major performed by The Four Nations Ensemble (here), and (2) the trio sonata in A major for pardessus de viole, violin and basso continuo (here) performed by Chrisophe Coin (on pardessus), which is on one of the recordings I own. Fantastic stuff, you’ll find that he manages to be highly intelligent and elegant at the same time. Just like conversation used to aim for in the good old days before tweets took over the world and trolls learned how to type (but not necessarily how to spell). 🙂

![]()

Johann Gottlieb Janitsch (1708-1763)

The name Janitsch has a decidedly Slavic ring to it and the biography of the composer soon gives fodder for suspicion that we have a Sorb on our hands. The Sorbs (info here) are a Slavic minority population in what is today eastern Germany. One of the Sorbian population centers, Silesia, was reabsorbed into Poland at the end of World War II (and the resident Germans were summarily tossed out, much to their abiding consternation). Whenever you see “tsch” at the end of a German name from the eastern part of the country it’s safe to say you have an assimilated Slav on your hands, in this case an assimilated Sorb or a person of Sorbian heritage. In Sorbian the name would be written Janič, which just goes to show how much bother a simple haček sign over a “c” can save you.

Janitsch was a thoroughly local boy, no trips to Italy or Vienna for study, always near the home turf. He came to music by the back door, as this information from his Wikipedia page (here) explains:

In 1733 Janitsch moved to Berlin for three years as secretary to the Prussian state and war minister Franz Wilhelm von Happe. In 1736, the then Crown Prince, Frederick offered him a position as a “Contraviolinist” in his ensemble in Ruppin and a year later, in Rheinsberg, where Janitsch’s home was destroyed in the great fire in 1740. During his time in Rheinsberg, with the permission of the Crown Prince, he founded the circle “Freitagsakademien” (Friday academies), in which music was performed by professional and amateur musicians alike.

From 1740, when Frederick ascended to the Prussian throne, Janitsch’s position as Contraviolinist was transferred to the newly founded Berlin Court Orchestra, where he was awarded a salary of 350 thalers. The Friday academies continued in Berlin in his home in the form of weekly concerts open to the public. This musical association was the first in a long line of similar organisations which arose in Berlin after 1750. From 1743, Janitsch was required to compose and organise “Redutenmusik” for the annual court balls held at carnival time by Frederick. The music was performed by 24 oboists, specially selected from various regiments of the Prussian army.

Outwardly his life was relatively tranquil. He wrote a lot of music and explored forms that were not common in the period, however, so underneath that tranquil surface churned the fires of invention. The works that draw the most attention in our day are the quadro sonatas, of which Janitsch wrote over 30. All of the recordings currently available of Janitsch’s music are of quadro sonatas, so he’s been somewhat pigeonholed in that box, which I’m sure does a disservice to the rest of his oeuvre. He wrote plenty of trio sonatas, orchestral music and large-scale vocal works, but the only aural evidence we have of him are the quadro sonatas, which seems a pity. The quadros are themselves a delight, however, so we’re lucky to have them, at least.

To be perfectly honest — and we keep no secrets between us — I find Janitsch’s music quite charming but not particularly compelling. It’s in the galant style reminiscent of a Boucher painting — it sets a mood and gives a pleasant picture but plumbs no depths of human experience in the manner of J.G. Graun, who takes you there and back again. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course. We need not all be Beethovens. Compared to the intellectual brilliance and emotional depth of Graun’s music, however, Janitsch’s sonatas strike me as competent and pleasant but of flesh at times a bit too thin to cover the bones. That said, I’d be very sorry indeed if somebody stole my recording of quadro sonatas performed by the Ensemble Notturna (available on Amazon). So there’s me for you, sitting on a fence yet again. Head over to YouTube, have a listen and decide for yourself.

![]()

Johann Heinrich Rolle (1716-1785)

With Rolle we come to another major songbird of the period. Like Homilius he has that Mozartean quality of effortless melodiousness. Lovely tunes seem fairly to drip from his pen. Lucky for us he’s been swept up in the Baroque revival in Europe and so we have several recordings of his works available — I own three of them and they’re fab, absolutely fab.

His life story is delivered in a single paragraph in his Wikipedia page (here):

Rolle was born in Quedlinburg. His father was a musician in Magdeburg, and in his early years Rolle served there as an organist while studying law. In 1741 he became a chamber musician in the court of the Prussian King Frederick II, before returning to Magdeburg in 1746 to take up the position of organist at St John’s Church. Rolle’s father died in 1751, and Rolle succeeded him as music director at the Altstädtisches Gymnasium, a secondary school. He died in Magdeburg, aged 69.

Rolle is remembered mainly for his oratorios.

He wrote in other genres, too, of course — keyboard music, chamber music — but to judge from the recordings available you’d think he was OratoriosRUs. Nothing wrong with that, a good oratorio is just like a good opera without all the carrying on and running about. I’m all for it.

I own three of the beasts: “Oratorium auf Weihnachten” (= Christmas Oratorio), “Der leidende Jesus” (= The Sufferings of Jesus) and “Der Tod Abels” (= The Death of Abel). The Christmas Oratorio is directed by Ludger Remy and appears on the CPO label. The other two works are directed by Hermann Max, your go-to boy for German Baroque period authenticity. The Christmas Oratorio is still available on Amazon but the other two are out of print, unfortunately. There are several things to listen to on YouTube so that’s my best recommendation at this juncture.

My all-time favorite piece by Rolle is a duet for soprano and alto, no. 5 in the Christmas Oratorio on the text “Ach, sei uns willkommen, du göttlicher Segen” (= We Welcome You, Divine Blessing). To be perfectly honest you could pass this off to me as Homilius and I’d probably fall for it. The lilting melody is there, the elegance, the compositional craft that weaves everything together into a tight and shimmering fabric — yes indeed, you could fool me into thinking it’s Homilius instead of Rolle. And if you did, where would be the harm in that? We’re all in this together, right? And good is good, no matter by what hand.

One final word on Rolle as a person. If you get hired at the court of Frederick the Great as a chamber musician, you’re no slouch. Let’s be clear on that point. Frederick was himself a musician and took his music very seriously, indeed, so he had no slouches on his music staff. Rolle’s appointment to the court musical establishment is itself proof enough of his rank in the order of the day. For someone with a court appointment then to abandon the court and return to a church organist position in Magdeburg speaks volumes. Obviously the pull of family and the old stomping ground was stronger than the bling of Sans Souci or the aesthetic stimulation of hobnobbing with the likes of C.P.E. Bach. That Rolle turned his back on the royal court and the life he had there fascinates me. He’s one of those composers I’d like to have to tea for a long chat. But have a listen to his music, you’ll think he’s from Vienna, not Magdeburg. 🙂

![]()

Christoph Schaffrath (1709-1763)

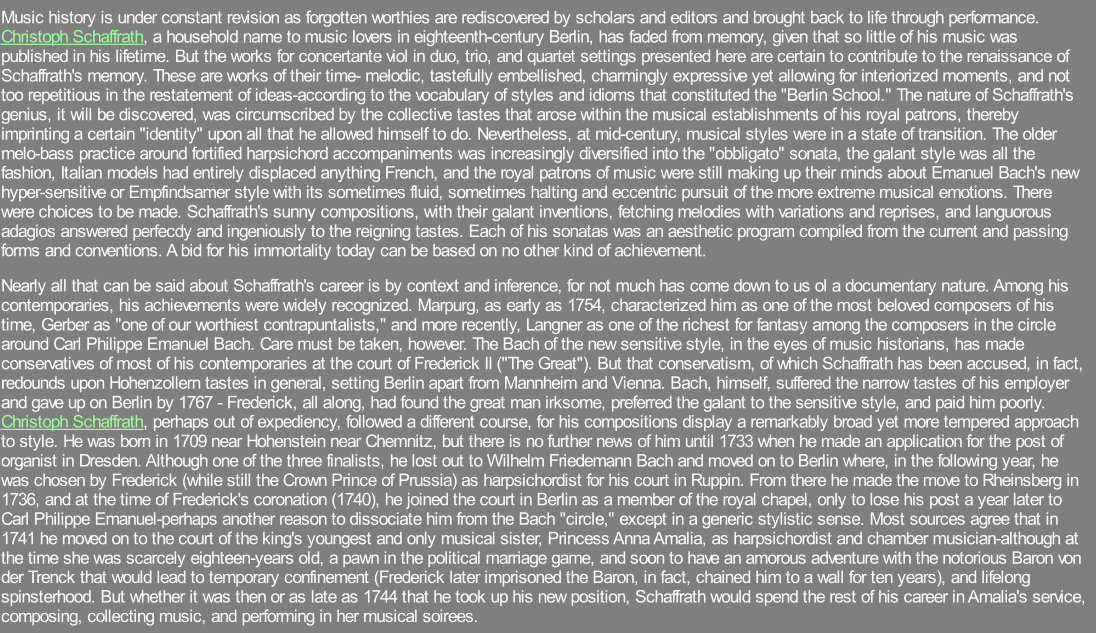

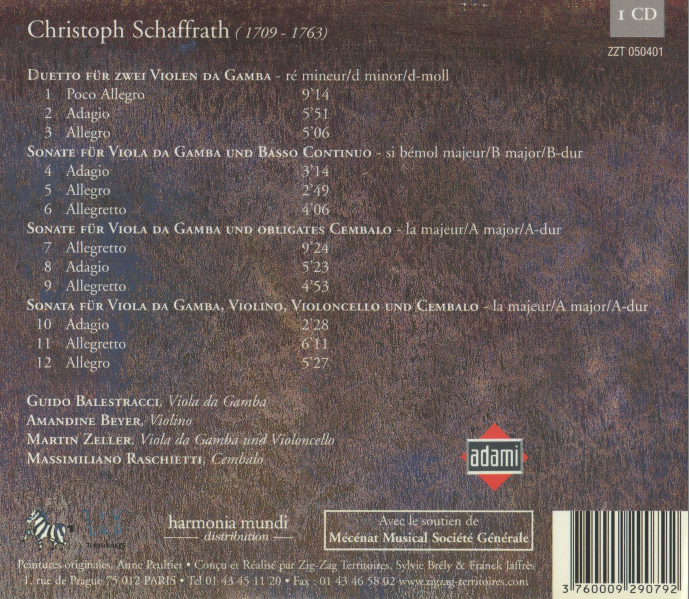

I’m not sure how such things happen but we’re up against a serious gap in knowledge when it comes to poor Schaffrath. It can’t be because of his music, since the music is next to Graun in its competence and intelligence. Who knows what undertows and whirlpools of history intervened to leave us in the dark. As is often the case, the best information comes from the liner notes of a recording of Schffrath’s music, a wonderful CD I own of music for viola da gamba performed by Guido Balestracci. Here’s the skinny:

The first sentence is spot on. On the basis of his compositional output alone Schaffrath deserves better than the near-oblivion he met with in the annals of music history. I know Schaffrath both as a listener and as a performer since I’ve played one of his sonatas for flute and obbligato harpsichord in concert. I was amazed when I first came across his music — exactly as the author of the note above opines so thought I. A very good composer, why have we not heard more about him? How good that his music is finally becoming better known. Here’s the verso of the CD by Balestracci:

You can hear the last piece, a very lovely quadro sonata, on YouTube here. It’s far more than competent, it’s really good stuff, extremely melodic and really interesting in the liveliness of the part-writing in the Allegretto movement. As a performer I can state for the record that his music is as much fun to play as to hear. Give it a listen and you’ll see what I mean.

![]()

Johann Schobert (1720?-1767)

While I’d never disparage the reputation of any other composer in this list by saying that we saved the best for last, we certainly have one of the most fascinating characters on our hands in the person of Johann Schobert. Let’s unpack the story, which is worthy of a spread in The National Enquirer.

Nobody knows his date of birth, which is estimated to be anywhere between 1720 and 1740 — a large enough span to include members of two different generations. Given that he died in 1767 I’m rooting for a birthdate around 1720 since it would have given him a decent lifespan, not a Mozartean brief stint before going out in a blaze of glory. Nobody knows exactly where he was born, either. Silesia appears to be the best guess, which would make him a compatriot of Janitsch. Someone of his caliber must have had a decent musical education but we’re completely in the dark on that account. Nothing is really known about him until he showed up in Paris about 1760 and started making a name for himself as a musician in the employ of Prince Conti. Apart from Schobert’s music itself his claim to fame is influence on a young W.A. Mozart. Here’s the skinny from his Wikipedia page (here):

In Paris, Schobert came into contact with Leopold Mozart during the family’s grand tour. Reportedly, Schobert was offended by Mozart’s comments that his children played Schobert’s works with ease. Nevertheless, Schobert was a significant influence on the young Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, who arranged a number of movements from Schobert’s sonatas for use in his own piano concertos.

Mozart biographer Dyneley Hussey writes that it was Schobert’s music that opened up Mozart to the possibility of adopting a poetic stance in his music. Citing Téodor de Wyzewa and Georges de Saint-Foix’s work on Mozart, Hussey points out that the four piano concertos, “which are deliberate studies from Schobert”, have a “typically Mozartian” stylized nature which is actually present in the Schobert works that he was emulating. Hussey concludes, “So we may regard Schobert, to whom Wolfgang owes so much of the ‘romantic’ element which appears in his work alongside of its ‘classic’ grace and vigour, as being the first of his real masters.”

In 1767, Schobert went mushroom picking with his family in Le Pré-Saint-Gervais near Paris. He tried to have a local chef prepare them, but was told they were poisonous. After trying again at a restaurant at Bois de Boulogne, and being incorrectly told by a doctor acquaintance of his that the mushrooms were edible, he decided to use them to make a soup at home. Schobert, his wife, all but one of their children, and his doctor friend died.

There in that last bit about the mushrooms you can see why I said his biography had something in it worthy of The National Enquirer. It pays to know your ‘shrooms, let that fact never escape our careful attention. I hope he had what can’t have been a very pleasant passing in his 40’s, not in his 20’s, which would put too keen an edge of pathos on things. In the short time he was in Paris he wrote and published an enormous amount of music. Here’s the opus list:

- op. 1 – 2 Sonatas for Harpsichord, Violine ad libitum

- op. 2 – 2 Sonatas for Harpsichord, with violin obbligato

- op. 3 – 2 Sonatas for Harpsichord, Violin ad libitum

- op. 4 – 2 Sonatas for Harpsichord

- op. 5 – 2 Sonatas for Harpsichord, Violin ad libitum

- op. 6 – 3 Triosonatas for Harpsichord, Violin and Violoncello ad libitum

- op. 7 – 3 Sonatas en quatuor, Harpsichord, 2 Violins and Violoncello ad libitum

- op. 8 – 2 Sonatas for Harpsichord with Violin obbligato

- op. 9 – 3 Sinfonies for Harpsichord, Violine and 2 Horns ad libitum

- op. 10 – 3 Sinfonies for Harpsichord, Violin and 2 Horns ad libitum

- op. 11 – Concerto I for Harpsichord, 2 Violins, Viola, Violoncello, 2 Horns ad libitum

- op. 12 – Concerto II for Harpsichord, 2 Violins, Viola, Violoncello, 2 Oboes, 2 Horns ad libitum

- op. 13 – Concerto III pastorale for Harpsichord, 2 Violins, 2 Horns ad libitum, Viola, Violoncello

- op. 14 – 6 Sonatas for Harpsichord, Violine ad libitum (Nr. 1 with Violin and Viola ad libitum)

- op. 15 – Concerto IV for Harpsichord, Violine and 2 Horns ad libitum

- op. 16 – 4 Sonatas for Harpsichord, Violin and Violoncello

- op. 17 – 4 Sonatas for Harpsichord, Violin

- op. 18 – Concerto V for Harpsichord and 2 Violins

- op. 19 – 2 Sonatas for Harpsichord or Pianoforte, Violin (posthumous)

- op. 20 – 3 Sonatas for Harpsichord and Violin (probably by T. Giordani)

It’s an astonishingly large body of work when one considers that all those opus numbers were published in the space of about seven years. I’d have been tickled pink to get just one opus number out a year let alone three or four. It must be nice to be talented …

Schobert’s music has its antecedents in the Germany of Graun, C.P.E. Bach and Schaffrath. In a way you could consider him to be C.P.E. Bach version 2.0, since he enjoys pulling the same tricks on his listeners, faking them out and jerking their expectations out of joint with great rambunctiousness. All that makes for exciting music for both performer and listener — and I have over 20 years of experience in both roles so my opinions are far from baseless, trust me.

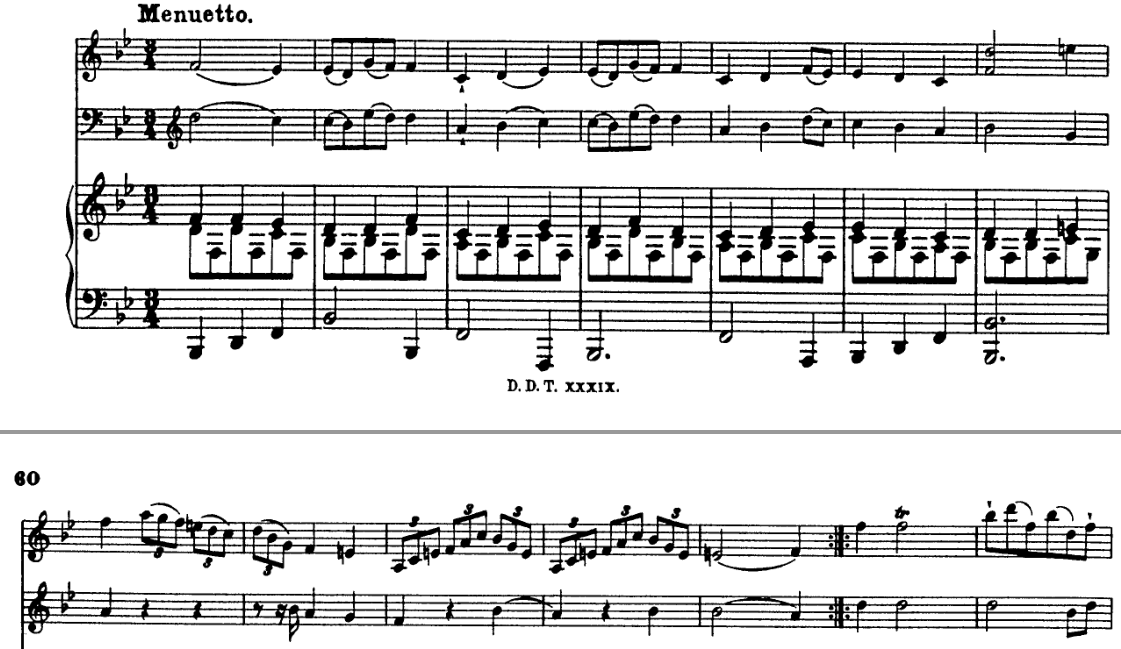

Along with all the daring-do and excitement there’s a great melodic gift at work, so Schobert acts also as a representative of the lyric strain of the German galant style as he plunges headlong into Beethovenesque pre-classicism. His lyricism surprises like that of Beethoven, coming when one least expects it. I’m thinking particularly of the sonata for keyboard, violin and violoncello (op. 16, no. 3) where the Minuetto movement is as songbirdy as you can get:

I’ve been listening to this particular piece for over 20 years and I still find it perfection, on the order of some of Mozart’s best melodies. Fantastic stuff.

The recording that introduced me to the magic of Schobert’s music is a performance (unparalleled IMHO) by violinist Chiara Banchini of Ensemble 415 fame and harpsichordist Luciano Sgrizzi. It’s long since out of print but you can listen to it on YouTube here. It remains entirely opaque to my understanding why Schobert’s music hasn’t taken off like a rocket in the Baroque revival craze of the past 30-odd years. Several recordings have been done but quickly went out of print, so if you go to find some you end up with very little in hand. Thank goodness things are available on YouTube so at least you can hear what we’ve been missing for the past couple centuries. Shouldn’t we pay more attention to somebody who took the fancy of W.A. Mozart? Of course we should. How silly of us not to realize that earlier.

![]()

I could keep going, of course, but in the interests of brevity I’ll stop here. Just because I didn’t mention the Big Names doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be devouring their music, too, of course — that goes without saying. I’m thinking particularly of C.P.E. Bach, W.F. Bach (his cantatas are too good for words), Carl Heinrich Graun (Johann Gottlieb’s opera-composing brother) and Johann Joachim Quantz, flautist to Frederick the Great. There’s so much lovely stuff to discover it fairly makes you tingly up and down the spine. Happy listening!