April 2019

I need to be honest with you. When I looked at the topic list for the month’s blog posts I saw I was down to a choice between writing about Hannah Arendt’s insights on totalitarianism and their applicability to the current political landscape — both in Europe and the United States, so great is our misfortune — or doing a piece on the French Baroque. I spent more hours than I care to admit on the post published last month about the prospects for American democracy after the country’s flirtation with authoritarianism currently in progress. The dangers of authoritarianism are fully worthy of address every week, every month, for many months to come, until we’ve managed to clear the minefield we currently traverse and our fingers relax from being crossed in the hope that no big explosions happen. Hannah Arendt is also fully worthy of consideration in the greatest detail possible. Her analysis of totalitarianism is so important it should be kept at one’s fingertips in days like ours. But my hair has been on fire so many times in the past few months I just couldn’t bring myself to tackle yet another stomp through the swamp. Consequently, we’re going to talk about pretty things this time, not nasty things that need to be discussed whether we want to or not. Okey dokey? Right, on we go then …

I need to be honest with you. When I looked at the topic list for the month’s blog posts I saw I was down to a choice between writing about Hannah Arendt’s insights on totalitarianism and their applicability to the current political landscape — both in Europe and the United States, so great is our misfortune — or doing a piece on the French Baroque. I spent more hours than I care to admit on the post published last month about the prospects for American democracy after the country’s flirtation with authoritarianism currently in progress. The dangers of authoritarianism are fully worthy of address every week, every month, for many months to come, until we’ve managed to clear the minefield we currently traverse and our fingers relax from being crossed in the hope that no big explosions happen. Hannah Arendt is also fully worthy of consideration in the greatest detail possible. Her analysis of totalitarianism is so important it should be kept at one’s fingertips in days like ours. But my hair has been on fire so many times in the past few months I just couldn’t bring myself to tackle yet another stomp through the swamp. Consequently, we’re going to talk about pretty things this time, not nasty things that need to be discussed whether we want to or not. Okey dokey? Right, on we go then …

You may wonder what the likes of me is doing going off at the mouth about French Baroque music since I don’t have any supporting initals after my name that might lend credibility to my opinions. Let me explain. Although I have no D.Mus. to put on my calling card, I do know a thing or two about French Baroque music. The reason? I studied it with a private teacher for a few years and have continued that study over my entire adult life as the amateur musician I’ve been. I’ve always had a special affinity for the French Baroque — I understand it in my very bones and have done since my first encounter with it. That understanding has enabled me to enter into its intricacies to a degree that found positive report from a source I consider quite credible: a professional harpsichordist of international repute who teaches at a European university.

I met him socially through a friend and went with my friend to visit him at his house where he had a luscious, and I mean LUSCIOUS two-manual French harpsichord. It made me drool as soon as I saw it. I asked if I might be allowed to play it and he gave me the green light. So while he and my friend sat and chatted I played all the pieces for the tenor range I could remember by composers such as Couperin and Balbastre. French harpsichords have throaty, full bass and tenor ranges and while I played I felt like I was getting the sonic equivalent of a Swedish massage. Fabulous. If the damned things didn’t cost over $25,000 a pop I’d have one myself. Eventually I joined the chat in the living room. As my friend took me back to my place he said, “By the way, he said your playing is really quite good.” That’s confirmation enough for me that I know what I’m doing when it comes to French Baroque music. If you still remain unconvinced then hang on, I’ll blind you with science. 🙂

National Styles in Baroque Music

It’s a curious thing that in the Baroque period it really did matter where music was composed. The differences between national styles are pronounced and French is perhaps the national style most firmly bound to its native soil. When a German attempts to write in the French style it’s never quite convincing, save in the case of those Germans who moved to France and in essence became French. In the area of keyboard music the difference is especially pronounced. Since I specialized in harpsichord I had to absorb the French keyboard tradition in all its complexities and subtleties, which I approached both academically and intuitively.

In French writing on music from the period you continually come across the term “le bon goût,” which means “good taste.” It serves as the gold standard for the interpretation of French Baroque music but nobody bothered to define it in very great detail. It’s one of those wink-wink-nod-nod things you’re just supposed to know if you’re in the right crowd — and if you’re not, you’re probably a plebe or an Italian LOL. Italians who tried to horn in on the French music scene consistently took a beating — e.g. Francesco Cavalli and Paolo Lorenzani. Both were invited to France and both left bruised and battered. After Cavalli finally got back to Venice he never left the city for the rest of his life. The music they wrote while in France was glorious, of course, there’s no doubt about that, but it wasn’t French. Therein lay the cause for all the brouhaha and the beatings about the head and shoulders.

The French musical establishment was ruled with an iron fist by Jean-Baptiste Lully, the chief composer to Louis XIV. But get this: Lully was an Italian. Yes, you read right. Born in Florence and went to France as a teenager, so he was as Italian as pizza. (He also happened to be a complete slimebag.) This lends an air of madness to the war waged between the musical camps supporting either the French or the Italian style, at its height between 1752 and 1754 and called La Querelle des Bouffons (info here). Nobody in Paris paid any attention to the German style — why investigate the musical goings-on of a bunch of rubes stuck out in the boondocks munching away on their Würstchen? Spain was just a short trip south but Spanish Baroque music was even farther beyond the pale than Italian for the musicians of Paris. Ah well, their loss — they missed cool guys like Christoph Graupner writing fantastic stuff at the court in Darmstadt. Chauvinism gets you nowhere but the French have never figured that out. Don’t hold your breath.

Le Bon Goût as Rhetorical Stance

So what makes the French style tick? It isn’t the architecture of the music as is the case with the German Baroque. The structural element in German music is paramount, the prime example of which is J.S. You Know Who. One is tempted to say that such music is logically concluded rather than composed because its structural elements are the base from which all else proceeds according to the rules of counterpoint and thematic development.

Nothing could be further from the case in French Baroque music. To get at the bottom of it we need to differentiate between architecture and sensibility. The two elements operate in such a way that at times they seem almost independent. The structural elements of French music (if I may be allowed to mix sociology and economics with musicology for a moment) reflect the rigid social order in which it was composed. Lully was an autocrat and ran a tight ship. The musical forms were trickle-down from the royal court. The result is a much greater architectural uniformity in French music than you find in either German or Italian music of the period. I am the first to admit that the rigid top-down approach was not always salutory in its effects. There’s a good bit of French Baroque music that sounds formulaic precisely because it is formulaic. As a composer I’d have chafed under such conditions of creation. I think of Christoph Graupner writing a concerto for four tympani — that would have gone over like a lead balloon in Paris, but they had great fun with it in Darmstadt and I’m always up for a good party.

A concerto for four tympani is music for extroverts. Such extroversion is not part of le bon goût because it lacks formality and restraint. It’s like peasants crashing through the underbrush chasing a pig who got out of the pen. We can’t be doing with that in the salons of Paris, can we. No, of course not. We must be tasteful at all times, otherwise we offend against the unspoken code of le bon goût and we’ll soon find ourselves kicked to the curb as Mme Such and Such reposes with a book of poetry open on her lap while listening to Monsieur Thus and So play the viol to the harpsichord with the greatest elegance, most probably eliciting faint sighs of sentiment from the ladies when the music turns particularly plangent.

So a big part of le bon goût is compliance with a social code of aesthetics, a willing subservience that reinforces the formulaic nature of the period’s music with regard both to structure and to performance practice. Another key element is refinement. The emotions expressed are put forth like tableaux to be recognized and appreciated by those in the know, who form an aesthetic elite. To those elements we may add the matter of precision. Many works, especially those for harpsichord, have elaborate introductions explaining exactly how to interpret the signs for ornamentation. Couperin is a good case in point. In German music you might find a trill indicated here and there but that’s about it. In French keyboard music the ornamentation is an integral part of the composition and must be given the greatest attention and care — all in good taste, of course, that goes without saying.

Underpinning all these things is an innate sense of style that operates like conscience. You know when things are right or wrong without needing to parse out exactly why. It’s a lived sense that infuses the performance and you either have it or you don’t. There’s nothing of the sort in the musical style of any other country in the Baroque period. You can mess up your counterpoint in German music and get on the wrong side of history as a result, but you’ll never be given demerits for offending against some unspoken aesthetic code involving your ornamentation.

As a performer French music puts you before a completely different reality than does German or Italian music. With German music your job is to find out how the piece works structurally and make that clear. With French music, however, you have to become a co-creator with the composer because what’s on the page is only part of the story. Your bon goût has to supply what’s not in the notation, which means if you don’t have it you’re in a pickle and Mme Such and Such will not be amused. Instead of sighing languidly at the beauty of your playing she may well call the footman for your coat and hat.

It was surprising to me to find that I have that lived sense. I can’t begin to explain how I came by it. It’s not something I consciously cultivated but I rely on it as my bedrock for the performance of French Baroque music. When I see what’s on the page I know it will only make full sense to me when I hear what it sounds like as my fingers press into the keys. From that sound I will assess what the piece is trying to say and what language it speaks to communicate its message.

And there we have the essentially rhetorical nature of the French Baroque. It’s like a conversation rather than a mathematical proof or a legal declination memo. Just as in a conversation, many different elements contribute to the meaning conveyed — silences, pauses, hesitations, all contribute to the discourse. So you must play as though you are speaking to Mme Such and Such in the refined, witty, intellectual and tempered language of the salon. The emotion you convey is delicate and highly nuanced. A slight glance, a slight hesitation before speaking the next word can carry great meaning.

A good example comes from the treatise Couperin wrote on how to play the harpsichord, L’Art de toucher le clavecin, first published in 1716. At the end he gives a series of preludes to illustrate his points. Here’s the first several bars of the first one:

To judge from what’s on the page you’d be forgiven for thinking that not much is going on. It’s all suspensions at a snail’s pace (although no tempo is indicated, which is typical). Let’s take the first note as a case in point. It has a mordent sign over it so you’re supposed to ornament it. But it takes up fully half the time value of the measure, so if you take your cue from the Germans you’ll be in big trouble. A single quaver of the tone will not cut the mustard. Because this mordent sign is over a half-note you need to make a statement with it. That means you have to invent something to make it rhetorically effective. There are lots of ways to do it, depending on what dialect you want to speak. You can start slow and build speed across the value of the note, letting the low C come down like a hammer to set the rhythm and ground the tonality. Or you can do a bird-like tweety kind of thing and let the low C come in gently, like a pebble dropping into a pond. It’s all up to you, the composer gives you absolutely no clues about his original intent. I have no clue how Couperin would have played it. I only know how the performers play it whose recordings I have. They differ considerably. That’s as it should be, because the performer is co-creator in such music, something that never happens with the music of J.S. You Know Who. With him you do as you’re told and if you have any objections you stifle yourself, thank you very much. Here’s an example:

This is engineered music, like a CAD drawing. As a performer you’re expected to follow the specifications and not get carried away with your own ideas. I feel like a technician when faced with such a composition. It doesn’t really matter how clever I am at understanding the music, my only real job is to hit the right keys at the right time. The interpretive elements — phrasing, articulation, etc. — are just gravy and can contribute to it sounding less like the clatter of machinery, but plenty of people play it in just that way and seem completely happy with the result. I don’t count myself among them.

Such things are worlds away from the doux monde of the French Baroque. Ladies listening to such mathematically-minded music don’t sit in rapt attention with books of poetry open on their laps. They knit and talk in whispers about recipes.

Given the creative challenge that’s an inherent part of performing French Baroque music it’s obvious why I gravitate to it as a musician — it requires great musicality of the performer, which is more than half the fun. The technical demands of the French repertoire are never as great as in the case of some other composers, e.g. Domenico Scarlatti. Only in the late phase of the period did a few French composers become bold enough to throw into the mix things like hand-crossing. Couperin would have been speechless with horror at the sight of such a thing. It’s never about fireworks because that offends against le bon goût. No vulgar displays of virtuosity, please — leave such things to Italians!

The example above by Couperin is one of my favorite pieces to play because of the intimacy that arises between the composer and the performer through the process of creating the rhetorical shape of the composition. When I finish playing it I have revealed as much of myself to the audience as I have revealed of Couperin — I hope, at least. This creative collaboration is unique to the French Baroque literature in my experience. If I didn’t have the innate chops to engage that process I’d find it completely mystifying and off-putting. You can’t just play what’s on the page, it won’t work. You have no choice but to speak the music in its own language, which can leave you flummoxed if it’s not native to you. I have no idea how to instill that quality in anybody. But hey, it’s art, not science. If you want science you can always turn your hand to J.S You Know Who. The only thing missing with him is the equations. 🙂

Some Stars in the French Baroque Heaven

I’d like to share thoughts on some of my favorite French Baroque composers. If you’re into early music you already know the big names — Couperin, Lully, and by this point Charpentier as well after 20-some years of a revival that has put him squarely (and deservedly) among the Big Wigs. Reputation in the 21st century is not my guide here. Personal experience of the music as a performer or a devoted listener of recordings in my own collection forms the basis for my assessment.

![]()

Louis-Nicolas Clérambault (1676-1749)

For a long time the only music of Clérambault (info here) easily accessible was his organ music. That’s how I became familiar with his works, through a Kalmus print edition I bought as a teenager. As the Baroque revival progressed through the decades since 1970 the full range of Clérambault’s oeuvre has come into view and I own recordings of his work in several different genres. There are 239 numbers in his opus list, the majority of them vocal music. You still don’t hear much about him but he occupied posts of great importance at major churches and worked for both Louis XIV and Mme de Maintenon, so in his own day he was indeed a Big Deal.

When you dig into the French Baroque it quickly becomes clear that there was an astonishing wealth of talent at work across the spectrum of the musical establishment. As is always the case with musical canons, only certain names become anointed as Big Deals. It’s the music of those composers that dominates the recording industry because companies need to make money and peddling the works of little-known composers is not a good way to get rich. The range and quality of Clérambault’s music makes it perfectly clear, however, that he deserves all the credit that can be steered his way.

Hervé Niquet with his group Le Concert Spirituel has been instrumental in getting a good sampling of Clérambault’s works out for aficionados like me to listen to. I own two of their recordings of works by Clérambault on the Naxos label. One features instrumental music and cantatas, of which Clérambault was a major proponent and an acknowledged master. The other is a performance of the pastoral drama Le Triomphe d’Iris. Both performances are absolutely scrummy. Here’s the cover of the pastoral work:

I’m grateful to Niquet and his group for making available to us examples of all the major genres of Clérambault’s oeuvre. The instrumental music is as good as the vocal music — inventive, intellectual and expressive at the same time, top-drawer stuff. The cantatas make it easy to see why Clérambault was considered a master of that form. They’re like miniature operas, full of dramatic and expressive tonal painting and wonderful tunefulness. Niquet’s group is also top-notch and I heartily recommend anything they do. He has enormous verve so sometimes the tempi seem to me a bit frenetic, but that’s a minor matter and shouldn’t hold anyone back from enjoying the fine performances he and his group always deliver.

I also own a recording of motets performed by Il Seminario Musical directed by Gerard Lesne, the fine French countertenor, issued on the Veritas label. It’s a fab recording filled with wonderful music performed brilliantly and it deserves a listen as much as do the recordings by Niquet. It captures the intellectual sophistication of Clérambault’s music while at the same time dripping with bon goût.

![]()

Marc-Antoine Charpentier (1643-1704)

There are relatively few big names in the French tradition — most of the Baroque superstars we consider as such come from Germany or Italy, to wit: J.S. You Know Who and Vivaldi. As I think about it I can’t say for sure whether someone with a love of Baroque music in general but without special knowledge of the French Baroque would know Charpentier (info here). He has certainly rocketed to top billing in the Baroque revival of the past 20 years for those devoted to French Baroque music. Many fine recordings of his remarkable works have been made by stellar ensembles like Les Arts Florissants under the direction of William Christie. In my estimation he’s in the top five French Baroque composers along with Lully and Couperin. He studied with Giacomo Carissimi in Italy so his musical idiom has Italian influence while remaining thoroughly French in spirit. His expressiveness goes far beyond the formulaic French musical conventions of the time, although he certainly knew how to write in that vein to excellent effect. His sacred music is heartfelt like that of Carissimi, so there must have been an affinity of temperament between teacher and pupil.

The first work I discovered of Charpentier’s was his Pastorale sur la Naissance de N.S. Jésus-Christ H.483 in the ravishing performance done by Les Arts Florissants under the direction of William Christie. It’s an astonishing work and I was gobsmacked the first time I heard it. I could hardly believe my ears. It remains to this day one of my favorite works by any composer, French or otherwise. Here’s the cover of the CD:

I also own recordings of Charpentier’s music by Le Concert Spirituel and they’re quite good. My opinion of the Christie recording of the Pastorale as a superlative stems no doubt from the background radiation of the supernova event I experienced on first hearing it lo these many years ago. I’ll bask in my prejudices and leave you to choose for yourself your own favorite. Charpentier is one of those composers who leaves me in wonderment at how any human being can produce such music. It’s beyond good. There are lots of recordings of his music in the marketplace now so you’re in luck. Have a listen.

![]()

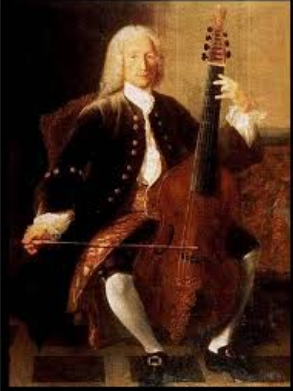

Louis de Caix d’Hervelois (1677-1759)

Here we have a proponent of the great French school of viol (aka viola da gamba) playing — the French were the foremost masters of the instrument throughout the Baroque period, although they had stiff competition from a few composers outside France such as the Dutchman Johannes Schenck and the German August Kühnel. The major names associated with viol music in France are, of course, Marin Marais and Jean-Baptiste Forqueray. De Caix represents a lighter vein of the tradition, a Rococo manifestation of the solid High Baroque article that both Marais and Forqueray represent.

My introduction to de Caix’s music was a recording of viol suites performed by Jordi Savall, who has no equal in the performance of the French Baroque viol literature. The CD is long out of print but you can hear a good bit of it on YouTube here. It’s music of pure delight, that’s the best way I can describe it. An air of cheerfulness, elegance and light-heartedness emanates from it. The first time I heard the recording I stopped dead in my tracks and thought to myself, “This is the very essence of the French Baroque.” My opinion hasn’t changed in 40 years, so have a listen and see what you think. Had I been listening to it in a French salon my attention would most certainly have been rapt and my book of poetry would without doubt have fallen open on my lap. Under no conceivable circumstance could my thoughts have turned to knitting or to whispering about recipes. 🙂

![]()

Michel Pignolet de Montéclair (1667-1737)

If I were in a position to do so I’d be standing on the musical equivalent of Speaker’s Corner in Hyde Park in London to broadcast far and wide the merits of Montéclair. In the hubbub of music history many people who deserve to held in remembrance get lost in the fray — the frequency of such occurrences in the annals of Baroque music is a matter for tears. So let me state here for the record that Montéclair deserves to be considered a Big Deal. I’ve known his music for over 40 years and my fondness for it has never abated, nor has my high estimation of its quality ever seen the slightest shadow of doubt.

He’s an example of someone born in the provinces who came to Paris and made good. This info comes from his Wikipedia page (here):

At some point between 1687 and the early years of the new century, he seems to have been maître de musique to the Prince de Vaudémont and to have followed him to Italy. It was probably from there that he brought the idea to add the double bass to the opera orchestra.

All the time Montéclair must have worked as a music teacher of high regard: among his pupils were the daughters of his colleague François Couperin. Montéclair’s approach to teaching was fresh and almost modern. He published books on teaching music (e.g., in 1709), and around 1730 he published Recueil de brunettes, which contains vocal music adapted for flute. The collection was expressly intended as a pedagogical tool to teach French style, and for this reason the music is underlaid with the text. He opened a music shop in 1721, retired from teaching in 1735, and gave up his position in the opera orchestra shortly before his death. He died in Domont in 1737.

Music can’t get any more French than the music of Montéclair. I say that because he’s the whole package, nothing is missing. Technical finesse, delicacy of expression, marvelous inventiveness within the musical conventions of the time and a great refinement of spirit. He’s known primarily for his cantatas, usually for solo voice with accompaniment of a small instrumental ensemble such as violin and basso continuo. I have a recording of some of his cantatas sung by the superlative French soprano Agnès Mellon who made a reputation for herself during the early decades of the Baroque revival as one of the finest interpreters of vocal music from the French Baroque. It takes very different chops than those needed for music from other Baroque national traditions because even in vocal music ornamentation was integral to the compositional approach. So to sing French Baroque literature you have to be light on your feet and nimble like Tinkerbelle. Ms. Mellon manages to accomplish with her voice what most of us do well to manage with our fingers on a keyboard. Hats off to her.

Recordings are hard to come by so if you want to give a listen head over to YouTube and you’ll find several examples of his works available. There’s even a complete recording of his oratorio Jephté, which is very much worth a listen.

![]()

Nicolas Chédeville (1705-1782) and Michel Corrette (1707-1795)

Due to the nature of French society at the time a cadre of composers arose who served the interests of the haute bourgeoisie and the Parisian nobility, who themselves took a practical approach to music. They played instruments and sang as part of their cultural life. That means they needed music to perform and teachers to give them lessons. Thus a cottage industry grew up that gave gainful employment to a particular set of composers who plied that trade and earned reputations for themselves not at court but in the musical circles of Parisian society. Some of them also built instruments such as flutes and musettes, the small bagpipe that became fashionable for women who fancied themselves shepherdesses à la Marie Antoinette in her Petit Trianon play farm.

Chédeville was one of these enterprising composers. He played oboe in the King’s band and was widely held to be the best musette player in France. From his Wikipedia page (here) comes this information about his professional activity:

Chédeville’s compositions were intended for the amusement and pleasure of wealthy amateur musicians; the French aristocracy of the time found pleasure in playing rustic instruments while living a romantic fantasy of peasant life (before the French revolution presented a rather different perspective).

His first published works were collections of pieces for musette or hurdy-gurdy, entitled Amusements champêtres (pastoral amusements), published in December 1729. He called himself ‘Chedeville le jeune’, and in later compositions referred to himself as ‘Chedeville le cadet’. Another collection of Amusements champêtres followed, which were of a more advanced technical and musical substance. Some variety was found in op. 6, with pieces named after battles and expressing ‘war-like images’; it was inspired by a military campaign he had gone on with the Prince of Conti. He turned briefly to more serious music with Italian influences in op. 7, which is his only collection written specifically for the flute, oboe or violin.

In 1737 he made a secret agreement with Jean-Noël Marchand to publish a collection of his own compositions as Antonio Vivaldi’s op. 13, entitled Il pastor fido. Chédeville supplied the money and received the profits, all of which was attested to in a notarial act by Marchand in 1749.[1] This may have been an attempt to give his instrument, the musette, the endorsement of a great composer which it lacked.

His interest in Italian music led to his receiving, in August 1739, a privilege to publish arrangements for the musette, hurdy-gurdy or flute of concertos and sonatas by ten specific Italian composers, in addition to Johann Joachim Quantz and Antoine Mahaut. Le printems, ou Les saisons amusantes (1739) is a particularly amusing result of this privilege; it is an arrangement of Vivaldi’s The Four Seasons for hurdy-gurdy or musette, violin, and flute (though the French flute could also mean the recorder). He replaced Vivaldi’s original Summer with his op. 8 no. 9 concerto, transferred the middle movement of Winter to Autumn, and replaced Winter op. 8 no. 12. All this was quite freely arranged and combined with some added Vivaldian material by Chédeville.

Busy guy. The music he wrote doesn’t scale any heights because that wasn’t the agenda. All the same, it’s lovely and tuneful and some of the pieces are great fun to play. I own a recording of his op. 9, Les Deffis, ou L’étude amusante, which contains some really charming character pieces. The performance is by Capella Savaria, a Hungarian original instrument group directed by Pal Nemeth. It’s great fun and oh so French.

Michel Corrette comes from the same circle and like Chédeville also came from Normandy, where his father, the composer Gaspard Corrette, was a celebrated organist in Rouen. He wrote an enormous amount of music and achieved great reknown as a pedagogue, publishing over 20 instructional treatises on various instruments. This info comes from his Wikipedia page (here):

Aside from playing the organ and composing music, Corrette organized concerts and taught music. He wrote nearly twenty music method books for various instruments—the violin, cello, bass, flute, recorder, bassoon, harpsichord, harp, mandolin, voice and more—with titles such as l’Art de se perfectionner sur le violon (The Art of Playing the Violin Perfectly), le Parfait Maître à chanter (The Perfect Mastersinger) and L′école d′Orphée (The School of Orpheus), a violin treatise describing the French and Italian styles. These pedagogical works by Corrette are valuable because they “give lucid insight into contemporary playing techniques.”

As a composer he was more wide-ranging than Chédeville and considerably more ambitious. My favorite for some time has been the collection of sonatas in op. 20 with the fanciful title Les délices de la solitude. The recording I own is played by Philippe Foulon on an instrument called a viole d’Orphée, described by Corrette in a treatise from 1781 as a viol strung with metal strings. It’s a unique sonic experience, that I will admit. Definitely worth a listen. There are several recordings of Corrette’s music available, among them the amusing pieces of the Concertos comiques. He also wrote large-scale works for the stage, chamber music and sacred works. The works I’ve heard show a sure hand and admirable skill with a definite Italian accent to the French goings-on, sometimes to the point of wholesale quotations from Italian composers like Vivaldi. The man could write a tune, that’s for sure, so check it out.

![]()

Elizabeth Jacquet de la Guerre (1665-1729)

Here she is in all her glory:

I’ve written about Jacquet de la Guerre in the post on women composers so I’ll keep it brief here. She was everything she appears to be in her portrait — cultured, intelligent, very successful as a composer and teacher and held in the highest esteem by the musical critics of her time, who were not an easy bunch to please, believe me.

Jacquet de la Guerre deserves extra credit for her accomplishments given the strictures the social order of her times imposed because of her gender. She couldn’t operate on the same professional level as her male peers although her abilities were on a perfect par. It didn’t stop her from composing, to be sure, but it severely limited her range of professional activity. Even so, she garnered the highest praise from the musical establishment of the time. When I listen to her music it’s quite clear to me that had she been a man she would have been one of the important composers of the French court.

I have a recording of her major opera, Céphale et Procris written in 1684 when she was 29 years old. It’s a work of great accomplishment and beauty. She mastered the strict conventions of the operatic form developed by Lully and wrote with enormous melodic inventiveness. The impression the work conveys is much more dramatic and immediate than any opera by Lully, whose stage works are formalistic in the extreme and subject all elements of the work to the social function they fulfilled as music of the royal court. The emotional accessibility of Jacquet de la Guerre’s opera is never overshadowed by the structural conventions to which she adheres. That makes her not only a better composer but also infinitely preferable from a human standpoint, since she wasn’t a complete creep like Lully. She was held in the highest esteem as a person. So she wins hands down on both counts in my book. Have a listen, you’ll be glad you did.

![]()

OK, that’s it for this go-round. As I go through my recordings of French Baroque music I’m tempted to add several more composers but I’ll stifle myself in the interests of brevity. I don’t know many people who share my passion for the music of the French Baroque. Too often one’s awareness of it is limited to the composers of the royal court. There are great delights to discover outside that august circle and I’ve had a wonderful time exploring them over the course of my adult life. My appreciation for the French national sytle has grown deeper with time. How fortunate we are in the 21st century to have the riches of that period opened to us in their fullness by the Baroque revival movemement. I’ll keep listening while I count my blessings.