April 2018

The iconoclastic wave has swept over me today once again and I can’t keep my mouth shut. So let me say it plain and simple: bugger Bach, let’s listen to something else for a change why don’t we? The unsung heroes of the Baroque period are as numerous as sands on the shore, and if I hear one more time that Bach is the be all and end all of Baroque music, I’ll go screaming into the night.

The iconoclastic wave has swept over me today once again and I can’t keep my mouth shut. So let me say it plain and simple: bugger Bach, let’s listen to something else for a change why don’t we? The unsung heroes of the Baroque period are as numerous as sands on the shore, and if I hear one more time that Bach is the be all and end all of Baroque music, I’ll go screaming into the night.

It’s been bubbling under the surface with me for years, long years. Even as a teenager I had it sorted out: I was a devotee of Heinrich Schütz at the ripe old age of 16, out in the wilds of the Pacific Northwest where the men are men and the deer are rightly nervous. I also built a clavichord from a kit at that age. You won’t believe me, I expect, and I could provide documentary evidence that would hold up in a court of law, but I’m not bothered because we’re among friends. Right? 🙂

I am bothered, however, by the obscurity of so many composers before whom we should bow down in gratitude. This untoward circumstance leads me to inquire about what conditions cause their obscurity and why. On the face of things, obviously, it can’t possibly be a question of questionable quality, or a lack of depth in feeling, or deficiencies in compositional skill, or any of the other criteria we use to define who’s a “good” composer and who’s not. Case in point: I’ve just discovered a trio sonata by Johann Gottlieb Graun — F major, for transverse flute, viola and basso continuo, GraunWV C:XV:83. I came across it on YouTube (available here), as so often happens these days, which makes me nod my head in agreement when somebody expounds about the blessings of technology. I listened to the first movement twice because I could hardly believe how much interest and invention Graun had packed into those 4-odd minutes of music. Then I Googled it and came up with a score in modern notation from IMSLP, another online resource before which I bow down and touch my forehead to the ground in gratitude. After hearing the first movement twice without the score in front of me, I then listened a third time with the notes before my eyes as I followed their progression. My ear is good, but I’m no Mozart capable of transcribing in toto the score of a piece I’ve just heard for the first time. Consequently, while I listened the third time following the score, I saw even more cleverness at work as bits and bobs of melodic material appeared transformed into submotifs in ways that had escaped my ear as the music flowed past them the first two times. At certain points I just sat shaking my head, stumped at how a human being can manage to think up these gossamer webs of sound. Over the course of my lifetime I’ve learned to play from the printed page with a fair amount of panache, but to sit down with a blank piece of staff paper and create something like that? No clue. It seems to me a miracle. Every time I chance upon a piece of music like Graun’s trio sonata, I see the light of creation dawn anew. And this piece is only one of hundreds that Graun wrote, so the wonders go on and on. But ask how many people know about Graun compared to those who’ve heard about Johann Sebastian, and you’ll soon find out there’s darkness afoot.

In my youth I developed quite a grudge against old Johann Sebastian, which is completely unfair, I quite realize now. He’s innocent of all wrongdoing in the matter of his musical canonization and during his lifetime he struggled like most other composers to earn his living and hold his place in the musical establishment. He certainly wasn’t considered an Act of God like he is now. These days I’ve nothing against the man, to be honest. But I do have something against his music: the majority of it bores the bejeezus out of me. There, I’ve said it — flame me if you will, excoriate my taste if you must, but I cannot recant. BOR-ING. And at the end of the day I have the CYA of de gustibus non est disputandem. I didn’t just make that up. Google it if you think I’m trying to pull a fast one. 🙂

Surely I’m not the only one who finds Bach dull. The major difference with me, however, is that I studied Baroque music with the harpsichord as my main instrument. Oops. I needn’t tell you that if you study harpsichord you’re going to end up playing Bach whether you will or no, and so did I. First it was the French Suites, forced to it against my better judgment by my teacher, who seemed to me like somebody pushing a dog’s nose into its own vomit to lessen the chances of it happening again. Then came the Toccatas, somewhat more interesting, actually a few rather rousing tunes now and again, but nothing to fire a huge enthusiasm. The organ works are in a different category altogether, of course, and when I studied organ works by Bach we got along rather well. Oh, there was a minor spat here and there, but we soon kissed and made up. Once I had to play the harpsichord part for somebody doing the violin sonatas (BWV 1001-1006). The one in G Major is actually not too bad, as long as you phrase it the right way. If you follow standard practice and play everything detached — or, God forbid, staccato — you end up with something that sounds like Sonata for Sewing Machine and Obbligato Knitting Needles, and the bass line sounds like it should be played by a Tennessee mountain band on a whiskey jug. Let us not even engage discussion of the slow movements, which give the effect of background music suitable for use in a funeral parlor. Spare me, please.

All the while that folderol was going on I was playing loads of other stuff. GREAT stuff. French stuff. Take, for example, the harpsichord pieces of Jean Henri d’Anglebert, whose unmeasured preludes are like a roller coaster ride at the Fun Fair. And then consider some of the pieces of François Couperin all in the tenor range: lovely, rich, sonorous, senuous stuff that made the harpsichord sound like a throaty crooner and gave me the feeling I should wear a trilby hat cocked at a saucy angle and dangle a cigarette out the side of my mouth as I tickled the keys. I got tingles up my spine every time I played them. Ooh la la. But during my studies it was inevitably back to Bach, clackety clackety thump, clackety clackety thump. When my teacher brought up the subject of Das Wohltemperierte Klavier — the Well-Tempered Clavier to us lowlifes — I dug in my heels. No way, I thought to myself, am I gonna play that crap. And that was the end of that. The pull of Fate drew me away from music into other means of earning a living (thank goodness, or I wouldn’t be sitting in the comfort I now enjoy as a retiree), and as soon as I could ditch Bach for good, I did. A bit of organ music now and again, the occasional cantata sinfonia (maybe), but no arias, thanks so much. How long has it been since I listened to a French Suite? Hmmmm … let me count the YEARS … but on second thought, who cares? I’m not going there again, ever. Check the face. Do I look bothered?

Over the many years I was active as a performer of Baroque chamber music, and as the academic information professional I was, I took on as a special task the work of unearthing as much music by obscure Baroque composers as I could find. With the research resources of a nationwide university network at my disposal, the search proved massively fruitful. I amassed so much music I had to build a database to keep everything straight. The music I discovered was a revelation of the first order. I realized that the standard texts on music history are useless for gaining a clear picture of the actual musical life of the period. We know now well enough that “history” as presented in those texts we were required to ingest during our youth is simply somebody’s perspective, never the whole story. If you take Grout as God, your idea of the Baroque period will be thin, anemic, pale and wan. In Darwin’s terms, it will be an evolutionary dead end because you’ll be stuck with Johann Sebastian at the apex of the pyramid and end up going nowhere fast. A good deal more went on outside Leipzig that nobody told us about. Let’s take one small but pregnant example over in Darmstadt: Johann Christoph Graupner.

Graupner’s musical output is even more ample than Bach’s: some 2,000 works in manuscript are held in the Graupner archive. From an organological perspective he was at the outer side of the cutting edge, using the chalumeau liberally in several of his works. Try finding a part for chalumeau in the works of You Know Who. There’s also a sinfonia, GWV 566, for six tympani. Try finding another example of that scoring in the Baroque period. Ain’t gonna happen. Graupner wrote over 1,400 church cantatas in addition to masses of orchestral music, chamber music, keyboard music, all of it stunning. Every new recording of Graupner’s music I acquire gives me new favorites to add to the ones I already had.

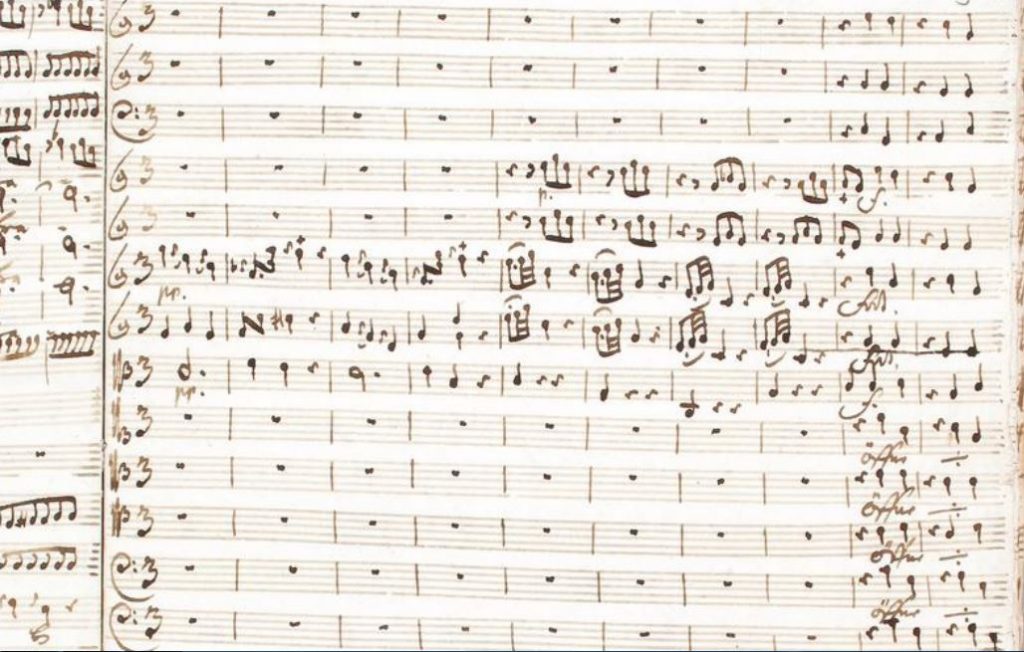

I’m an old fart myself now (no need to rub it in) so my experience long years ago as a student happened before the great explosion of musicological research that has rescued some of the geniuses of the Baroque from their earlier obscurity. Graupner is among the rescued, thank heavens. The Ensemble des Idées Heureuses, directed by Geneviève Soly, has made Graupner’s music a special focus of their performance and recording work, and I bow down before them in gratitude. Florian Heyerick has also jumped on the bandwagon and produced very fine recordings of church cantatas by Graupner. Listening to one of his recordings brought me face to face — or better said, ear to ear — with a choral movement from the cantata “Gott sei uns gnädig und segne uns” (Be Merciful, O Lord, And Bless Us) GWV1109:41 on the text “Jesu öffne deine Hände” (Jesus, Open Thou Thy Hands). My experience on first hearing was exactly the same as the one today with Graun’s trio sonata: I was reduced to shaking my head in wonder at how someone can come up with such fantastic stuff. I’ve listened to a very great deal of Baroque music over the last 40 years but I can’t point to the like of this chorus in anybody else’s oeuvre. Have a look (full score here):

Graupner, Jesu offne deine Hande incipit

What fresh magic is this? Three sound blocks: strings, a pair of oboes, and the full chorus. And most unusually in Baroque music, indications for dynamics — “pp” at the beginning, which is very soft. So in come the strings on tippy toes with the oboes doing a quiet point of punctuation in a figure that recalls an Alpine horn call sounding at a great distance. Then wham up side your head the choir comes in, all four voices SATB at once, KABOOM, and off the first beat, not on it. Anybody who knows their stuff about Baroque music knows that the first beat of the measure is a big deal for a Baroque composer, so clearly Graupner is tossing convention to the winds to catch us off guard. The strings and oboes flit about delicately for eight measures firmly attached to the first beat, then the choir crashes the party on the second beat of the ninth measure. Good on you, Graupner. Fake us out why don’t you LMAO. And almost immediately comes another surprise:

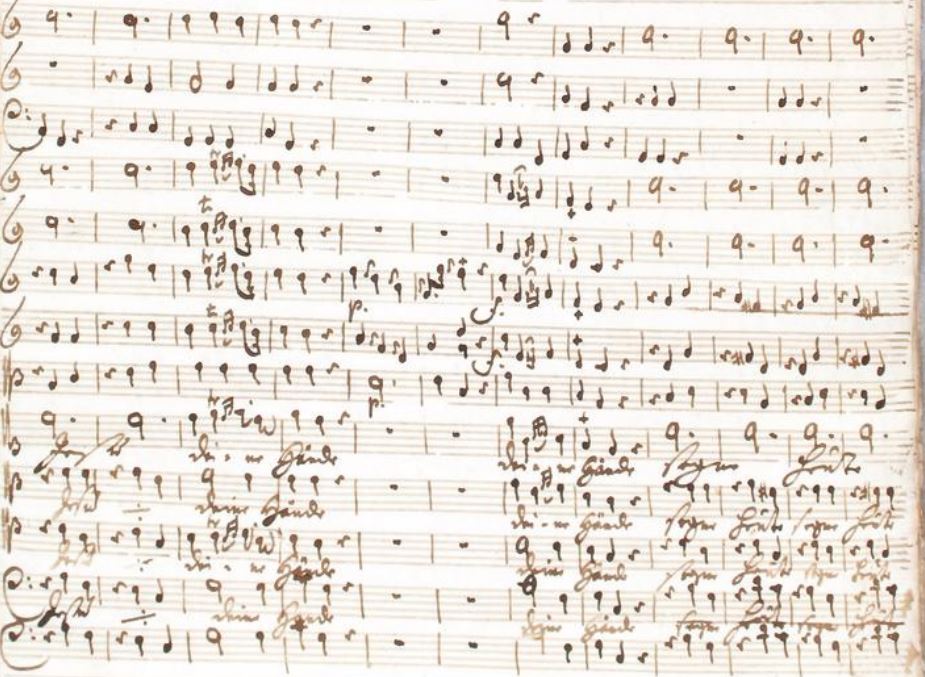

Graupner, Jesu offne deine Hande, choral figure

Graupner tosses the rhythmic and melodic differentiation between the sound blocks into the bin and has the soprano and tenor lines do a trill — a long trill — in unison with the strings. For we are all one in our Lord Jesus Christ, right? That’s the word on the street, anyway. The choir goes suddenly from gallumphing to having a goodly number of adult voices doing an extended trill together, which in choral writing of any period is worth an eyebrow raised in surprise. But it’s also a stroke of genius. It binds together the disparate sound blocks so that the ear drops its penchant for patterns and opens to the surprise. No, Bridget, the strings will not always go pp-ing around doing filigrees, and the choir will not always sound like Godzilla stomping across New York City. But who will do what when? Seeing what happens next is the FUN bit. FUN. Let’s not forget that word in association with Baroque music I’ve heard that chorus many times by now and I know the score very well, but a sensation of surprise still overtakes me when I listen to it. It’s the inventiveness of Graupner that occasions the feeling, of course. The man was a genius. I am surprised continually, delightfully by seeing the mechanics of his genius at work.

So my next question is: WHY DID WE NOT HEAR ABOUT HIM SOONER? Well, to answer that question we move from music to sociology, and I think we’d be well served to call in our dear friends Adorno and Horkheimer for a bit of critical theory. I did graduate study in German and it’s the same damned thing there, too. Goethe, Goethe, Goethe, oy gevalt kindele enough with the Goethe already! How about a romp through the madcap world of Grimmelshausen? Woohoo! Much has now been written about the institutionalization of literary canons and how they’ve propagated themselves insidiously into the curricula of higher education — and yes, I speak as a survivor, I got the flipping T-shirt. But I kicked up a fuss, too. Bad me. I wrote one paper detailing how if you follow Goethe’s tendencies to their logical outcome you end up with: the Biedermeyer. OMG shut up, he said what?? Well, I did, and my argument was so convincing that I got an A on the paper although the professor told me I had no business writing such things as an M.A. student. Too bad, so sad. Facts is facts, babes. Deal with it. The process of canon establishment in music history is the same bloody thing. Things got hijacked by some old farts, that’s the entire story in a nutshell.

Now that I’m an old fart myself there’s no way I can carry on in this fashion without throwing stones in glass houses. More’s the pity. I’ll have rather large bills for replacement glass, no doubt, because I’m not about to change my ways. It’s the old farts we have to blame for all this nonsense about “best” composers of a period, old farts from the 19th and early 20th centuries who made the lists and decided who was a sheep and who a goat. The major problem with those old farts is their abysmal ignorance of the musical richness of the period, which in the second half of the 20th century finally came fully into view at long last. I’d be happy to sit down with Grout and the score of Graupner’s cantata and have it out with him, point by point, until one old fart or the other, the music historian or Yours Truly, lies bloodied and vanquished on the floor.

But there’s no need for such extreme measures. The problem is removed with the adoption of one simple principle: everything counts. How simple is that? Everything counts, I don’t care who the composer is, everything that has been composed counts as something worthy of attention along with everything else. You like it or you don’t like it, period end of story. You think it’s good or it’s crap, point final. I don’t care if you’re a Distingushed Professor of Old Fartness, your opinion is just an opinion. True, you may know a bit more about 17th century counterpoint than I do, but who cares? In the grand scheme of things, you’ll be dead sooner rather than later and somebody else will come along who knows even more than you do, because history is largely hidden and acquires a larger and broader basis with every succeeding generation. So the old farts who wrote music histories in the early to mid-20th century belong on the slag heap. They drone on and on about the likes of Johann Sebastian and forget everybody else. Any music history of the Baroque period that doesn’t go into serious detail about Graupner is garbage, in my opinion. His oeuvre is a treasure trove. It hardly takes a PhD in musicology to perceive that fact. So let’s undo that tacky bit of ideology we call canon formation and replace it with: everything counts.

Perfect. Done and dusted. There’s tons of stuff on the menu now, kids, and you can have it ALL.

So bugger Bach and give me some Graupner for a change. After all, harpsichordists just wanna have FUN 🙂