May 2020

I’ve always loved the viola da gamba and have collected recordings of its literature for donkey’s years. I also owned a bass viol for several years and enjoyed playing it although I never reached a particularly high level of accomplishment. I managed to perform in concert Telemann’s sonata for recorder and viola da gamba from Der Getreue Musikmeister (TWV 42:F3) holding forth on the solo viol part — that was the highest peak I conquered. There were plenty of summits never reached, as well, and I never even tried to grapple with the French literature, which would have been tantamount to musical self-immolation. Knowing as a player the ins and outs of the instrument leaves me all the more respectful of the accomplishments of those in the professional class. My purpose in this post is to strike a balance between the seriously geeky and newbie levels in discussing composers whose works for viola da gamba form what I consider highlights of my own collection, There are the canonical Big Deals — composers like the Frenchies Marin Marais, Ste Colombe, Antoine Forqueray, and Teutons like J.S. You Know Who with his sonatas for viola da gamba and obbligato harpsichord — who justifiably receive a good deal of the attention and have tons of recordings in the marketplace. I’d like to single out some lesser-known composers who should IMHO be Big Deals, as well. I hope by so doing to amplify the range of composers whose works fit into the must-haves of somebody like me who loves the instrument and its literature. So let’s get started, moving in chronological rather than alphabetical order so we can follow the trajectory of the literature across time. There’s a lot of ground to cover and I’m going to have to do a Pippi Longstocking on myself, giving strict orders to keep the list to manageable proportions. It could easily balloon, but I’ll be stern with myself, not to worry. 🙂

I’ve always loved the viola da gamba and have collected recordings of its literature for donkey’s years. I also owned a bass viol for several years and enjoyed playing it although I never reached a particularly high level of accomplishment. I managed to perform in concert Telemann’s sonata for recorder and viola da gamba from Der Getreue Musikmeister (TWV 42:F3) holding forth on the solo viol part — that was the highest peak I conquered. There were plenty of summits never reached, as well, and I never even tried to grapple with the French literature, which would have been tantamount to musical self-immolation. Knowing as a player the ins and outs of the instrument leaves me all the more respectful of the accomplishments of those in the professional class. My purpose in this post is to strike a balance between the seriously geeky and newbie levels in discussing composers whose works for viola da gamba form what I consider highlights of my own collection, There are the canonical Big Deals — composers like the Frenchies Marin Marais, Ste Colombe, Antoine Forqueray, and Teutons like J.S. You Know Who with his sonatas for viola da gamba and obbligato harpsichord — who justifiably receive a good deal of the attention and have tons of recordings in the marketplace. I’d like to single out some lesser-known composers who should IMHO be Big Deals, as well. I hope by so doing to amplify the range of composers whose works fit into the must-haves of somebody like me who loves the instrument and its literature. So let’s get started, moving in chronological rather than alphabetical order so we can follow the trajectory of the literature across time. There’s a lot of ground to cover and I’m going to have to do a Pippi Longstocking on myself, giving strict orders to keep the list to manageable proportions. It could easily balloon, but I’ll be stern with myself, not to worry. 🙂

![]()

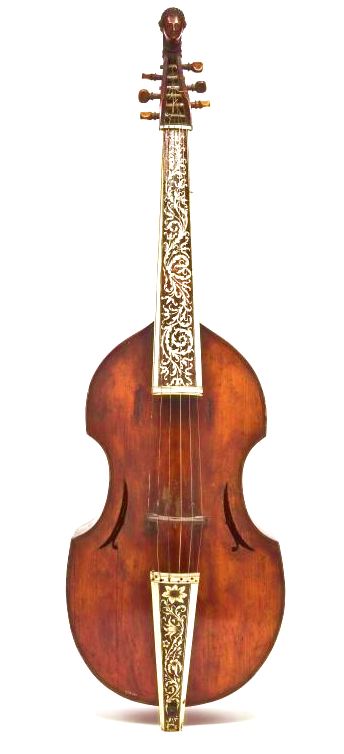

Diego Ortiz (Spanish, 1510?-1576?)

A short and sweet but meaty bio comes from the HOASM website (here):

Spanish composer. Worked from 1555 to 1570 at the vice-regal court of the Duke of Alba in Naples. His publications consist of a volume of sacred music (hymns, Magnificats and motets) and a treatise of outstanding importance on viol playing, the Tratado de glosas sobre cláusulas y otros géneros de puntos en la música de violones of 1553. This is a noteworthy source of Renaissance ornamentation and improvisational practice, containing variations on stock basses, arrangements of madrigals where the viol plays ornamental figures to a keyboard accompaniment, cadential embellishments and so on. His techniques led to the English ‘divisions on a ground’ and the improvisatory, viola bastarda style.

It’s thought he was born in Toledo and we lose track of him in Rome, which is where it’s assumed he died. The importance of his Tratado de glosas makes him a good place to start — the first composer to reach renown specifically in association with the viola da gamba. The following text from a recording of pieces from the Tratado by the inimitable Jordi Savall gives a good overview of Ortiz’ compositional baseline:

I have two recordings of pieces from the Tratado, one of them a complete recording by Bettina Hoffman and the other a selection of works by Jordi Savall. The Savall recording is by far the more satisfying, truth be told. The Hoffman recording is certainly competent from a musical standpoint but not what I would call inspired and sonically speaking it’s well below par, the viol sounding pinched and strained in a struggle to hold its own against the accompanying instruments. Savall’s recording is sonically rich and his playing is, of course, superb. It’s an older Astree recording that’s still available on Amazon, I’m happy to report. There’s a wealth of tracks on YouTube, as well, so you’re in luck. Have a listen and see where the enormously important literature for solo viol got a major start. You’ll be glad you did.

![]()

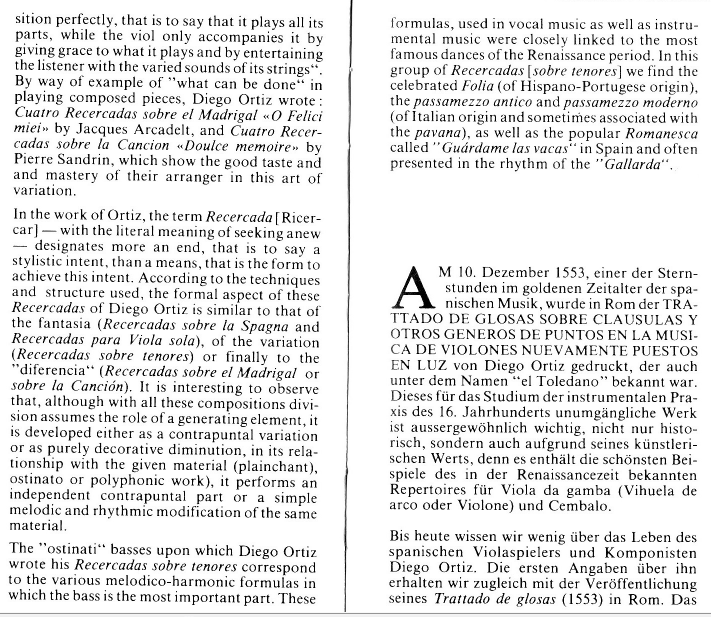

Christopher Simpson (English, c. 1605-1669)

Somebody with a snarky tongue might suggest that he looks like his main man, Charles I, having a bad hair day … The facts that Simpson’s dates are a full century after those of Ortiz and that he still fits squarely into the Renaissance scheme of things tracks the pokey progress of musical taste in England. If Simpson had been Italian he’d have been writing in a completely different idiom — that of the Early Baroque, with contemporaries like Dario Castello and Girolamo Frescobaldi. But there’s nothing of the Baroque about Simpson. This is his bio from the HOASM website (here):

English composer, theorist, and viola da gamba player. He fought on the Royalist side in the English Civil War (1643-44), and later was employed by Sir Robert Bolles. His tutoring of Sir Robert’s son John (b. 1641) occasioned the writing of The Division-Violist (London, 1659; 2nd ed. 1665), praised by Jenkins, Coleman, and Locke; its practical approach to instruction is reflected in the titles of its three sections: “Of the Viol it self, with Instructions how to Play upon it,” “Use of the Concords, or a Compendium of Descant,” and “The Method of ordering Division to a Ground.” About 1663 he bought an estate near Egton. Another of Simpson’s pupils, Sir John St. Barbe, inspired The Principles of Practical Musick (London, 1665), which became the Compendium of Practical Musick (London, 1667). Simpson’s instrumental works are all for viol, with or without other instruments, and vary in difficulty.

If you’re a gambist you inevitably come across Simpson because of his treatise The Division Viol, which is available on the IMSLP website here. Coming across his music is another matter entirely. For that reason I’m all the more grateful for a recording of works by Simpson done by Sophie Watillon with a fine group of musicians that I consider one of the treasures in my collection. Here’s the cover:

It’s enormously fortunate that the entire recording is available on YouTube here because it’s no longer available on Amazon save in the marketplace at absurdly high cost. There’s a facsimile edition of The Seasons available from Minkoff, but I find no edition available of The Monthes. This circumstance suggests that Ms. Watillon and Co. have done some serious digging in archives to cobble together the manuscript parts for the two sets of works, something we amateur gambists find well beyond our means to accomplish. The music is so lovely I’d cry crocodile tears if anybody snatched my copy of this recording. As a harpsichordist I was fascinated to learn that the instrument used for the recording has gut strings, not the usual brass, which creates a lute-like sound that blends wonderfully with the viols. All things considered, then, this recording belongs in the top drawer for consort music of the period quite apart from its value in being unique as a vehicle for purveying to us the music of a composer whose music is very hard to lay hands on. Two thumbs up to Watillon and Co. for their good work, may it continue long into the future.

![]()

August Kühnel (German, 1645-1700)

We’re now in the Early Baroque period, no more dawdling about in the Renaissance. Even amateur gambists may not readily come across Kühnel since he’s not for the faint-hearted (read: technically challenged). Here’s some biographical detail from his Wikipedia page (here):

August Kühnel (3 August 1645 – ca. 1700) was a German composer and accomplished viola da gamba performer. He was born at Delmenhorst.

Kühnel was the son of the Mecklenburg chamber musician Samuel Kühnel. Already in 1661 (at age 16), after receiving education in Güstrow and France, he was appointed Violdigambist in the court orchestra of Maurice, Duke of Saxe-Zeitz, a position he held until 1681. After the duke’s death in 1682, Kühnel went to England to study. In 1686, he was appointed director of instrumental music at the Darmstadt court by Countess Elisabeth Dorothea von Sachsen-Coburg where he remained until 1688. After jobs in Weimar and Dresden, he found his last job in 1695 at the court of Charles I, Landgrave of Hesse-Kassel.

Kühnel’s main instrument was the viola da gamba for which he also wrote numerous compositions. In 1698, his first collection of trio sonatas for viola da gamba was published as 14 Sonate ò Partite ad una o due viole da gamba, con il basso continuo and printed in Kassel. This collection includes 6 sonatas for two gambas and 8 sonatas for one gamba. This was the first printing of German trio sonatas in Germany.

I found some interesting information from the website of Harmonia Early Music, a podcast from Indiana Public Media (here):

It was during his tenure in Kassel that Kühnel put out his one and only publication: the Sonate ô partite for one or two viols.

Kühnel’s style in these pieces defies an easy categorical box. The baroque German-Netherlands virtuoso viol school, with which Kuhnel is associated, had roots in the English division style championed by composers like Christopher Simpson. But as the 17th century progressed, German viol players added to the standard English figurations when they started to imitate the latest virtuoso techniques of Austro-German violinists like Schop and Biber.

It’s interesting because of the link to the trajectory of solo violin music in the Early Baroque, when the literature exploded with works such as the Rosary Sonatas by Heinrich von Biber. In Germany, the Netherlands and France the bass viol took up the lower end of the sonic spectrum as the solo instrument of choice rather than the cello. England continued with the tradition of the viol consort well into the Baroque period, with even so thoroughly Baroque a composer as Henry Purcell still writing music for consort rather than music for solo bass viol. On the Continent, however, the era of the solo bass viol had arrived for good.

Kühnel is also important from the standpoint of music history because of his occupation of a slot that the Baroque opened up: the acknowledged virtuoso/composer. It’s a trope that will carry forward through the Classical and Romantic periods without losing a beat. With regard to music for viola da gamba in the 18th century it’s the French who will take things to their pinnacle in the fantastic roster of virtuosos/composers from the reign of Louis XIV. It’s from that period of the High Baroque that the Big Deals of the French literature come, names like Marin Marais and Antoine Forqueray. But it started with people like Kühnel, who also studied in France let us not forget, so the inception of the tradition was an international affair.

The recording of Kühnel’s works in my collection is the performance by The Spirit of Gambo (a name nicked from the title of a piece by Tobias Hume, who appears in my post on Renaissance composer shoutouts). They’re a Dutch group who play wonderfully well. I don’t find their recording on Amazon, more’s the pity, but a great stroke of luck turned it up on YouTube in its entirety, available here. Pay attention to the techniques used in the solo sonatas as you listen, you’ll see that they take their cue from the fireworks that occur in solo violin literature of the time, including double and triple stops and passagework done at breakneck speed, wholly satisfying musically but definitely intended to show off your chops as a virtuoso.

There’s another recording I want to mention although I don’t own it — I’ve heard some tracks from it and it’s great. The inimitable duo Les Voix Humaines (Canadians Susie Napper and Margaret Little, who nicked for their name the title of a piece by Marin Marais) did a recording of duo sonatas from Kühnel’s collection performed very handsomely. There are some tracks from it available on YouTube, e.g. Sonata No. 1 in F Major here. In contrast to the recording by The Spirit of Gambo, it is indeed available on Amazon, which is good news. In my opinion Kühnel too often goes missing among aficionados of early music save for those gamba geeks like me who dig about to find it. His music is lovely and deserves a careful hearing no matter what your favorite instrument happens to be. Give it a try and see for yourself.

![]()

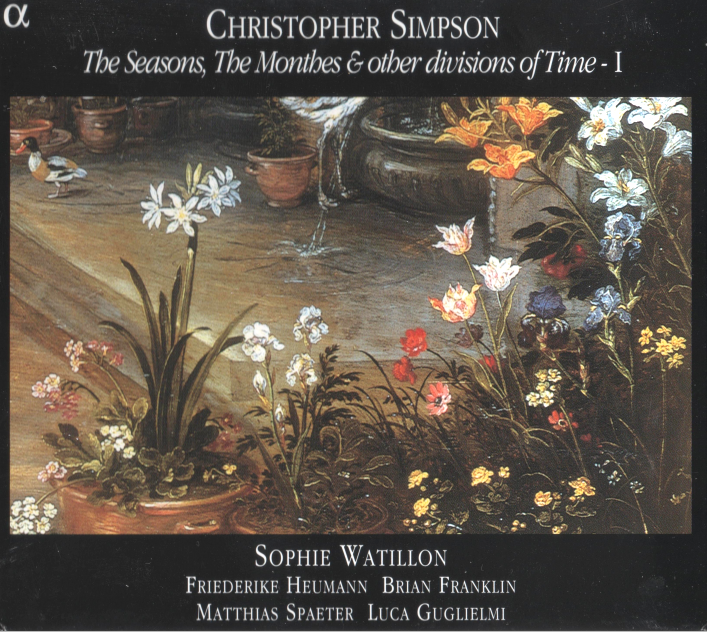

Carolus Hacquart (Flemish, 1640-1701?)

Pretty cool shoes, and note the carved rose on that hefty bass viol. How people managed to play the instrument with all that lace flopping about I’ll never know. I’d have got a jump start on the Industrial Revolution by inventing rubber bands to keep the sartorial finery under control. Just saying. 🙂

Hacquart was born in Bruges (modern-day Belgium) but spent the greater part of his adult life in the Netherlands, fetching up in both Amsterdam and The Hague. He published an opera in his youth — the very first one in Dutch (ooh la la, see below under Schenck LOL). He cobbled together a living as a musical gig worker, basically, benefitting from some connections to folk in high places, as his Wikipedia page (here) explains:

Three other publications of his music have survived. His first published work is the Cantiones Sacrae, which consists of religious pieces for vocal soloists, choir and instrumentalists which could be sung by both Catholics and Protestants (1674). His second published work is the Harmonia Parnassia Sonatarum’, which is a collection of 10 sonatas for two or three violins and basso continuo (1686).

His third published work: Chelys (1686). The work Chelys consists of 12 suites that can be performed by one viol, two viols or one viol with a basso continuo accompaniment. Only one copy of the gamba part of Chelys survives. The bass part is lost.

The work of Hacquart belongs to the best music composed in the 17th century Netherlands. In particular the instrumental sonatas from his opus 2, Harmonia Parnassia Sonatarum stand out.

Obviously it’s the collection Chelys that concerns us here. I own a recording of suites from it performed by Guido Balestracci, who plays the music athletically as it demands. Here’s the cover:

There’s a goodly bit of similarity between the suites of Hacquart and Schenck, who figures next in our list, so let me just say here that Hacquart shows the early curve of the trajectory that Schenck would carry to its apex in later decades. Both the handsomeness of Hacquart’s music and the vigor of Balestracci’s playing make this recording a must-have for any gamba geek like me, that goes without saying. I’d suggest it as a worthwhile addition for anyone fond of Baroque instrumental music, simply on the compositional merits of the music alone. Besides, just think what kind of points you can score when you bring up Hacquart’s name at the next cocktail party you attend, mingling his name into the small talk (while maintaining appropriate social distancing, of course). All that and gamba, too. Yeehaw. 🙂

![]()

Johannes Schenck (Dutch, 1660-1712?)

The bio from the HOASM website (here) is (as usual) succinct and information-rich:

Dutch Composer and viol player. It seems that Schenck spent the earlier part of his career in Amsterdam where his compositions included music for a Dutch Singspiel, Bacchus Ceres en Venus, from which songs were published in 1687, as well as works for his own instrument. Enjoying a wide reputation as a performer, in about 1696 he moved to Düsseldorf to the court of the Elector Palatine Johann Wilhelm, known as Jan Wellem, who ruled there from 1679 until his death in 1716, establishing a court that aimed to rival the artistic magnificence of Versailles. Here Schenck served with a group of musicians drawn from various countries. The court opera, which had been seen in Amsterdam, flourished with, among other operas, Kapellmeister Sebastiano Moratelli’s Il fabbro pittore, based on the life of the Netherlands painter Quentin Matsys, which had been staged in the Elector’s art gallery in 1695. His successor Johann von Wilderer’s La monarchia stabilitia was mounted with singular splendour for the visit to Düsseldorf of Carlos III of Spain in 1703. It was to the Elector that Corelli dedicated his concerti grossi and from Düsseldorf that Handel, who visited the court in 1710 and 1711, was able to recruit the famous castrato Baldassari. Other musicians of distinction connected with the Düsseldorf court included briefly the great lutenist Sylvius Weiss, together with his father and brother, while, in 1715, the violinist-composer Veracini performed there.

Schenck is presumed to have continued in the service of the Elector until the latter’s death in 1716. Thereafter the electoral court moved to Mannheim, followed by a number of the Düsseldorf musicians, who formed the nucleus of a musical establishment that was to win its own unchallenged reputation, as the century went on.

Doubts as to the date of Schenck’s death, presumably in Düsseldorf, come from the lack of any mention of his death in Protestant church records in the city. From this it has been supposed that he may well have become a Catholic, following the religion of his employer, and there are no Catholic records for the probable period of his death. He is mentioned in a document by the court cabinet secretary Rapparini in 1709, but by 1717 his name had disappeared from the list of court opera musicians then compiled.

I like to think that Schenck went back to the Netherlands and lived out a long and well-deserved retirement among the windmills and the clogs and the fat rounds of Gouda cheese. Since all trace of him disappears in 1712 when he was only 52 it’s as likely a scenario as any other, is it not?

Among gambists Schenck is considered one of the Ascended Masters but because his shtick was the bass viol he’s never reached canonical status outside the gamba geek community. Since he was a virtuoso the music he wrote is not for the rank amateur. It doesn’t scale the technical heights of say, Forqueray, but it’s not something you sit down and sight-read through at your monthly early music gathering (the highlight of which is dessert) as your collection of the Great Unwashed plods its way through transcriptions of Renaissance madrigals with some of the tricky bits smoothed out, which Gladys on the tenor recorder still can’t play so you have to stop every two measures (just. shoot. me.). No, there’s none of that with Mijnheer Schenck, thank you very much. This is proper solo viol music written with intimate knowledge of the instrument and its sonorities, so it deserves a performer who can do it justice. I did not count myself among that illustrious lot when I was playing bass viol. Would that I could have done, but you either pull it off or you don’t and it’s not rocket science to determine which of those two mutually exclusive states obtains. I’ll hope for better luck in my next lifetime. 🙂

I own five recordings of music by Schenck:

- his opera Bacchus, Ceres en Venus

- Scherzi musicali op. 6

- Le Nymphe di Rheno op. 8 (2 vols.)

- L’Echo du Danube op. 9

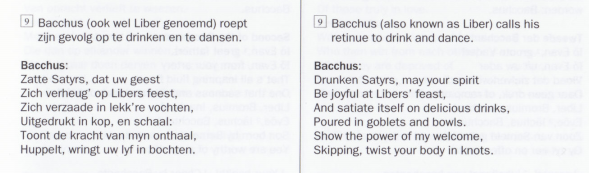

The opera is an early work and quite accomplished. It shows that Schenck could have developed compositionally into a Big Deal on the scale of any other Big Deal of the day but his path lay in other directions. The opera is allegorical, as was the fashion of the time, and what’s even more interesting, the libretto is in Dutch. Before acquiring the recording of Schenck’s Bacchus I had never heard an opera sung in Dutch. I can’t say I find the experience particularly edifying. Having been in Holland and found myself astonished at some of the sounds issuing from people’s mouths, the reason is not far to seek. I’m reminded of a line from the film Amadeus spoken by an Italian court composer who remarks apologetically that German is a language “too brutal for singing.” One shudders to think what he would have said about a libretto in Dutch, which has even more plosives and gutturals in operation. Here’s an example:

Most every “g,” every “h” and every “ch” is a whooshing sound of the sort one might make when poked in the ribs. The cumulative effect is not particularly salutary. Being bladdered as Bacchus suggests wouldn’t necessarily improve the situation, although it may take the edge off the auditory shock if the proceedings are far enough progressed. In any case, once this opera was accomplished Schenck published only music for the viol and it’s exquisite. To judge from his portrait I expect that to hear him play his sonatas would have been elegance itself.

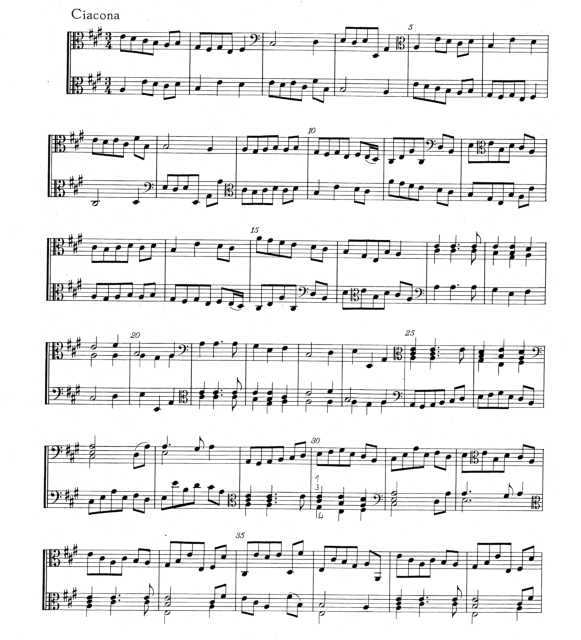

I have a favorite piece by Schenck, the Ciacona from Sonata IV in A Major of Le Nymphe di Rheno, suites for two bass viols without basso continuo. The music is so sweet it will melt your heart like chocolate in the palm of a toddler. Here’s the first page of the score:

The recording I own is by the inimitable duo Les Voix Humaines (Susie Napper and Margaret Little) who are top drawer across the boards. It’s a Naxos recording in two volumes still available on Amazon. I recommend it wholeheartedly. There are lots of tracks of music by Schenck on YouTube, including some from the selfsame recording by Les Voix Humaines, as well as others played by well-known gambists such as Wieland Kuijken, Lorenz Duftschmid, François Joubert-Caillet and lesser-known but wonderful performers like Lixsania Fernández, a young Cuban-born gambist based in Spain who’s making quite a name for herself. If you’re like me you’ll want Schenck recordings in your own collection so you have them locked in. Schenck is not optional in my musical life, he’s in the essential category. Have a listen and I bet you’ll think the same.

![]()

Gottfried Finger (Moravian German, 1655-1730)

Finger came from what is today the Czech Republic, but back in his day it was Moravia (Mähren), a province of the Holy Roman Empire under the Habsburg Emperor in Vienna. Because of Habsburg (and hence German-speaking) dominance in the Czech lands there were a lot of Teutons floating about. Many of them ended up leaving for Germany or Austria in order to make their way as musicians, which is exactly what Finger did, except he kept going until finally he reached London where he became a member of the expat musical community. Here’s the biographical skinny from information available on the Arkivmusic website (here):

Finger was born in Olomouc in Moravia and worked there in the famous ensemble of the Prince-Bishop Karl Liechtenstein-Kastelcorno, in whose archive at Kromeriz Finger’s earliest compositions are preserved. Finger was probably in Munich in 1682 and may have arrived London as early as 1685. Against stiff competition he received a post in James II’s new Catholic chapel in 1687. In 1688 he published his Op. 1, dedicated to James II, and intended for use in the Catholic chapel.

When James II went into exile in 1688, Finger remained in London and started a successful freelance career and became a central figure in London’s musical life. He published several popular collections aimed at the growing amateur music market, including the first set of sonatas for solo instrument and continuo ever to be published in England (1690). He was especially successful as composer for the theater, a part of his career that seems have begun in 1684, though his career in England came to an abrupt end when he entered the competition in 1701 to set Congreve’s masque The Judgment of Paris and came only fourth, beaten by John Weldon, John Eccles, and Daniel Purcell. According to Roger North, “having lost the cause, Finger declared he was mistaken in his musick, for he thought he was to be judged by men, and not by boys, and thereupon left England and has not bin seen since.” Finger then returned to the Continent and held posts at several important cities, including Breslau (Wroclaw), Berlin, Heidelberg, Dusseldorf, and Mannhiem; at the latter he laid the foundations for the Mannheim orchestra later made famous by Stamitz.

There’s a name in the first paragraph that should make us snap to attention: Kromeriz. Properly: Kroměříž. The town is nowadays a UNESCO World Heritage Site. From the Wikipedia page (here) on the stylus fantasticus — a florid, virtuosic style of instrumental music imported from Italy to Germany and the Habsburg lands — comes this important information:

In Austria the style was practised by the famous formidable virtuoso Heinrich Ignaz Biber and the older Johann Heinrich Schmelzer.

In summer the Prince Bishop of Olomouc [i.e. said Karl Liechtenstein-Kastelcorno] and his court retired to Kroměříž Castle, where there were lavish musical entertainments. Ballets such as The Fencing School and descriptive pieces such as [Biber’s] Battalia or The Peasants go to Church. Kroměříž Castle then was newly built by the Prince Bishop, the original medieval structure having been destroyed by the Swedes towards the end of the Thirty Years’ War. Jacob Handl had worked at the old castle between 1579 and 1585. The discontinuity in musical life and musical training due to the Thirty Years’ War explains the originality and the folksiness of the stylus fantasticus at Kroměříž. Though Bishop Karl was fanatically interested in music, and is principally known in England as a patron of Biber and Schmelzer, he was the driving force behind the restoration of the economy of Moravia after the destruction of the Thirty Years’ War.

In other words, Kroměříž was one of those nests of genius from which composers radiated who later became famous in other parts of Europe, like Heinrich von Biber who rocketed to fame in Salzburg. In such an environment, with such composers in his ambit, Finger developed as a virtuoso and composer. His viol music shows clear traces of the stylus fantasticus with its virtuosic elements, particularly in the free-form fantasias that begin the suites for viola da gamba.

It leaves one perplexed why that auspicious beginning didn’t carry over into Finger’s later legacy. People who have truck with amateur early music circles may well come across Finger’s name as a composer of recorder sonatas. He wrote a good many of them in addition to violin sonatas and a large number of trio sonatas, probably a by-product of his freelance career in London when he had to make a living teaching and writing music accessible to people like his students. Few of his works have been recorded — he occupies at present the position that Telemann occupied in the past, a composer considered suitable for sheet music editions destined for amateurs but not for serious recording projects.

Two recent recordings are working to change that mistaken and sorry state of affairs. The excellent group L’Echo du Danube (who nicked their group name from a title by Schenck) has recorded Finger’s opus 1, Sonatae pro diversis instrumentis, the collection published in 1688 and dedicated to James II, in what is IMHO an electrifying performance. Equally electrifying is Petr Wagner’s performance in his recording of the complete works for solo viol by Finger. Here’s the cover:

Happily the recording is still available on Amazon. You can watch a fantastic performance by Wagner of the Sonata No. 2 in D Major on YouTube here. It gives you a good sample of the kind of playing you’ll find on the recording. I can’t recommend it highly enough. As with the music of Hacquart and Schenck, it’s a fine addition to the collection of anybody who loves instrumental music of the Early Baroque whether or not you’re a gamba geek. As an aside, you can hear L’Echo du Danube’s recording of Finger’s opus 1 sonatas on YouTube here. The music has to my ear a strong northern German element to it and reminds me of the ensemble sonatas of Buxtehude and Bruhns. Definitely worth a listen, give it a try and you’ll be glad you did.

![]()

Louis de Caix d’Hervelois (French, 1670-1759)

I was spared the agony of choosing among the Big Deals of the French viol school — the Major League of viol playing in the High Baroque period — by simply choosing my favorite composer among them, Louis de Caix d’Hervelois. Done and dusted. I loved de Caix’s music the first time I heard it and that hasn’t changed over the past 30 years. It never will until I’m not listening to music anymore due to having attained the same state as de Caix. 🙂

Rather than parade biographical information before you I’d like to provide this encapsulation of de Caix’s style in a review by Barry Brenesal from Fanfare magazine, available on the Arkivmusic website (here):

Although he wrote more than 300 pieces for the bass viol, d’Hervelois is not mentioned in any surviving literature by his contemporaries. That noted, his work does turn up in several manuscripts of the period devoted to collections of viol music, alongside such worthies as Forqueray and Marais, who were among the most celebrated viol players of their time. His music must have sold well, too, as he published quite a bit of it, with the financial aid of his sponsors. Even a Maecenas of a patron such as d’Orléans wouldn’t have financed an inferior musician. As for the four suites that comprise the composer’s Third Book, they display the French suite at a stage in its evolution where the original series of dances (frequently a prelude, allemande, courante, and sarabande, but with other combinations possible) was being gradually abandoned in favor of collections of character pieces. Each of d’Hervelois’ suites begins with a prelude, more songful than profound; two change midway into much faster music, as though each were a prelude within itself. Beyond that, the mix of dance movements is completely individual. The First Suite includes a sarabande, rondeau, and two rigaudons, while the Third Suite supplies an allemande, two menuets, a gigue, and a musette.

All of the selections are relatively short and uncomplicated, with one- to three-part contrapuntal textures dominating. They strive for neither the grandeur of Marais nor the fiery brilliance of Forqueray, but possess a direct charm entirely their own. Rhythms are infectious, and the thematic content pleasant, if unmemorable. “Le Baron,” set as an elegant, graceful dance, refers to a famous actor of the period; “La Michel,” whoever he might have been, is as sanguinary and garrulous as the finale to Nielsen’s Symphony No. 2. Did “Les Vendengeuses de Montguichet,” the Monguichet vineyards, provide an especially dry, lively vintage to match d’Hervelois’ drily witty, lively music? Then there are the folk pieces, such as the rigaudon of the Second Suite that imitates the hurdy-gurdy perfectly, while the Third Suite’s musette does as much for the French bagpipes. Few of these selections last longer than two minutes; that referring to the vineyards above lasts less than one. The portraits and dances aren’t vivid in the way that those by Rameau or Couperin le Grand are, but they share one virtue with those by these masters: They never outstay their welcome.

For me de Caix is the quintessence of the French Baroque. Always elegant, always carefully but effortlessly within the bounds of le bon goût, that hazy concept composed of good taste, good spirits and everything else that went to make the culture of the French Baroque the Be All and End All of European civilization in the 18th century, de Caix’s music is formulaic but never trite, never stilted and always as transparent as diamond in its heartfeltness. It’s easy music to love with its tunefulness and its sunny disposition.

The first recording I ever heard and for many years the only one I owned was the one made donkey’s years ago by the inimitable Jordi Savall. It first came out on vinyl — do you young thangs even know what I’m talking about? LOL — but I bought the CD so was at the time a thoroughly modern Millie. The recording is available by track on Amazon (Astree Digital Edition) and can be heard on YouTube here. The neglect visited upon de Caix’s music passeth understanding since it’s fully the equal of Marais’ IMHO. But there’s the operation of the canon for you, obscuring the truth from view rather than helping one find one’s way toward it. A pox on it …

![]()

Thus endeth our survey. The end came much more quickly than I would like, there’s tons more to share from the treasures in my collection. To close let me mention some of the other names worthy of investigation if you’re after good recordings of literature for the viola da gamba. And if you’re ever interested in looking at instruments for sale, Charlie Ogle’s workshop has a full range available at violadagamba.com — one-stop viol shopping, what could be better? 🙂

- Matthew Locke (English, 1621-1677) Great consort music in the English tradition.

- Joseph Boudin de Boismortier (1689-1755) He wrote fantastic duos for two bass viols in addition to sonatas and other music with viola da gamba solo parts.

- Dietrich Buxtehude (German, 1637-1707) Primarily known as a composer of organ music and cantatas, his chamber music has wonderful parts for the bass viol that make for exciting listening.

- Michel Corrette (French, 1707-1795) Corrette wrote a set of sonatas for bass viol called Les délices de la solitude (op. 20) which has been recorded by Philippe Foulon on the viole d’Orphee, a bass viol strung with metal rather than gut strings. The recording is fantastic and one of my favorites. You can hear it on YouTube here.

- François Couperin (French, 1668-1733) Couperin is of course considered one of the canonical greats of harpsichord music but he also wrote very lovely music for the bass viol with continuo. Pierre Pierlot has done a great recording of it with the Ricercar Consort, available for listening on YouTube here.

- Defense de la basse de viole. This recording (available on YouTube here) by Philippe Pierlot and the Ricercar Consort is devoted to the music of French composers for the viol whose music is otherwise impossible or difficult to find, including Jacques Morel (1700-1749, a pupil of Marin Marais), Jean-Baptiste Cappus (1689-1751), Roland Marais (1685-1750, the son of Marin) and de Caix. A treasure for anyone fond of viol music.

- Le Sieur de Machy (French, fl. 1655-1700) One of the first generation of virtuoso/composers for the viol in France, along with his teacher Nicolas Hotman. Jordi Savall has done a great recording of pieces by de Machy available on YouTube here.

- Charles Dollé (French, fl. 1735-1755) A fine but little-known composer of viol music in the great French tradition. The Czech gambist Petr Wagner has done a recording of his music which is superb.

- Antoine Forqueray (French, 1672-1745) With Marais one of the two Biggest Deals in the French viol literature. He’s the Parnassus which modern gambists climb to reach the pinnacle of their career and you’ll find a wealth of performances on YouTube. Go crazy. As a harpsichordist I’d also like to point out the arrangements for keyboard Forqueray’s son Jean-Baptiste did of works by his father, who was as quarrelsome a creature as may be and had his son first imprisoned in 1719 and then exiled in 1725. There’s quite a miniseries there for the asking, sounds like to me. It would make Dallas look like having tea with the archbishop. 🙂

- Johann Gottlieb Graun (German, 1703-1771) Together with his brother Carl Heinrich, an opera composer, Graun was active in Berlin during the reign of Frederick the Great. He wrote wonderful concerti for viola da gamba and superb chamber music in which the viol figures as one of the solo instruments. A recording I own and treasure is Konzertante Musik mit Gamba done by Christophe Coin and the Ensemble Baroque de Limoges which features music by Graun, two concertos and two trio sonatas one of which has two bass viols and the other violin and pardessus de viole, the treble member of the viol family popular in the latter part of the 18th century. The recording is available for listening on YouTube here. I’ve written about Graun in other music posts, he was one of the best composers of instrumental music of the entire High Baroque in my opinion. Fantastic stuff.

- Franz Xaver Hammer (German, 1741-1817) Hammer worked as a gambist/cellist with Haydn at the Esterhazy Palace in Hungary. His compositions include music for both viol and cello. The recording I own is called Franz Xaver Hammer: the Last Gambist and includes five sonatas performed by Simone Eckert. The entire recording is available for listening on YouTube here. To be perfectly honest, the music is nothing particularly noteworthy, but it’s interesting to hear the viol used in music that’s already sliding toward the Classical period in the last decades of its use before it fell into oblivion.

- Le Sieur de Sainte-Colombe (French, 1640-1700) He was Marin Marais’ teacher and a famous performer in Paris in his own right. His claim to fame is the collection of works for two bass viols entitled Concerts à deux violes esgales, essentially duos for two bass viols without continuo. They are great music and another Parnassus for the big names among professional gambists, including Jordi Savall and Wieland Kuijken and the duo Les Voix Humaines (Susie Napper and Margaret Little), the performers on the recordings I own. The Savall/Kuijken recording is available on YouTube here. The recording by Les Voix Humaines is also available in two files on YouTube, the first of which is available here. It’s reported in contemporary accounts that Sainte-Colombe often performed with his two daughters so I expect he’d give Napper and Little a big thumbs up. I certainly do.

- Marin Marais (French, 1656-1728). Marais is to French viol literature what Colonel Sanders is to fried chicken. He’s the Biggest Deal of the lot and there was even a movie made about him and his teacher Sainte-Colombe, Tous les matins du monde (All the Mornings of the World), based on the novel by Pascal Quignard. Jordi Savall did the performances used in the soundtrack. I saw the film and somehow I suspect that Marais was far less adept at jumping in and out of bed with various winsome examples of the prototypical French wench and far more concentrated on getting his triple stops nailed down to perfection. In any case, Marais’ music is lovely and recordings of it are a dime a dozen. I own the early ones done by Jordi Savall in the late 70’s and issued on CD by the Astree label. I haven’t updated my collection to include performances by later gamba stars.

- Carl Friedrich Abel (German, 1723-1787) Abel was from Saxony, the son of a gambist and conductor and studied with J.S. Bach at the Thomasschule in Leipzig. Like Bach’s son Johann Christian, Abel ended up in London where he was a chamber musician to Queen Charlotte, that woman reputedly of such scant charm. The connection between the two German musicians led to the famous Bach-Abel concerts, the first subscription concerts offered in England. His music is in the style galant, of course, just like J.C. Bach’s. Nima ben David gives an excellent performance of Abel’s most famous piece for viol, Arpeggio in D minor, available for viewing on YouTube here.