July 2019

One of the tourist hotspots in the Coffee Triangle is the town of Filandia, situated about 30 km (19 miles) from Pereira and nearly equidistant from Armenia, the capital of Quindío, the department in which Filandia lies. It’s an easy get from either city. If you search the Internet for information on Filandia you’ll get the impression that it’s a traditional coffee town holding on to its traditions and its past as a center of the traditional life associated with coffee growing. You’ll expect to see donkeys and guys looking like Juan Valdez milling about the place. And you’ll perhaps be astonished as I was to discover that Filandia is an arts and crafts center that looks considerably upmarket and has the tourist red carpet thrown out in every direction. On first visit it reminded me of Northwest Portland, with lots of shops selling trendy handmade articles, natural toiletries like soap and hand lotion, and cafes offering specialty coffees on every corner. The only guys milling around who look like Juan Valdez are touts trying to get you into their restaurant or their tourist attraction and I saw not a single donkey loaded with bags of coffee. The young man who took us through the cultural museum of basketry right off the main square was in his early twenties, had blonde highlights bleached into his head of curly black hair, sported an earring in each ear and wore a T-shirt that said “I [Heart] New York.” So much for quintessential traditional coffee culture in the heart of Quindío.

One of the tourist hotspots in the Coffee Triangle is the town of Filandia, situated about 30 km (19 miles) from Pereira and nearly equidistant from Armenia, the capital of Quindío, the department in which Filandia lies. It’s an easy get from either city. If you search the Internet for information on Filandia you’ll get the impression that it’s a traditional coffee town holding on to its traditions and its past as a center of the traditional life associated with coffee growing. You’ll expect to see donkeys and guys looking like Juan Valdez milling about the place. And you’ll perhaps be astonished as I was to discover that Filandia is an arts and crafts center that looks considerably upmarket and has the tourist red carpet thrown out in every direction. On first visit it reminded me of Northwest Portland, with lots of shops selling trendy handmade articles, natural toiletries like soap and hand lotion, and cafes offering specialty coffees on every corner. The only guys milling around who look like Juan Valdez are touts trying to get you into their restaurant or their tourist attraction and I saw not a single donkey loaded with bags of coffee. The young man who took us through the cultural museum of basketry right off the main square was in his early twenties, had blonde highlights bleached into his head of curly black hair, sported an earring in each ear and wore a T-shirt that said “I [Heart] New York.” So much for quintessential traditional coffee culture in the heart of Quindío.

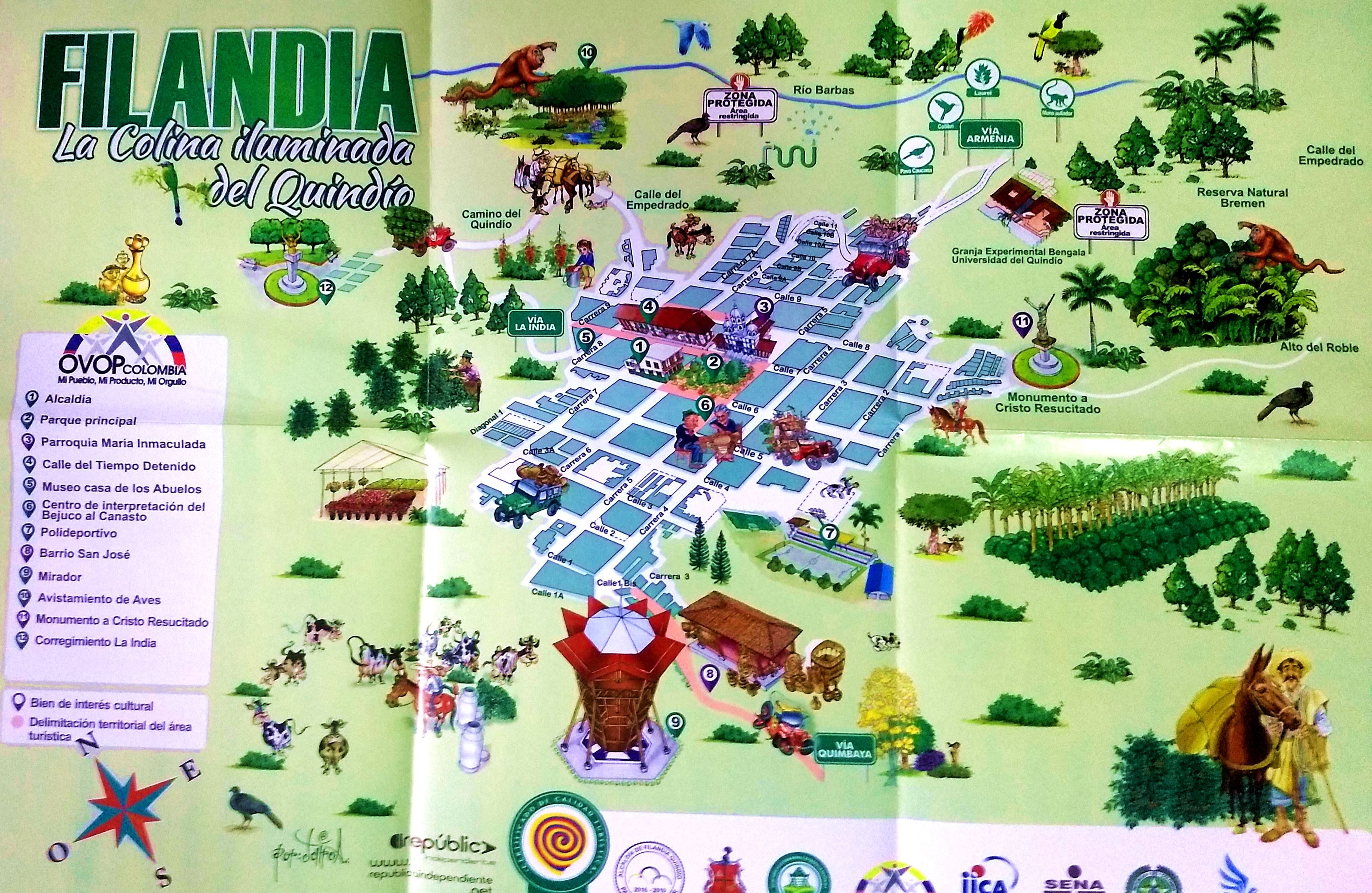

But it’s all very lovely. There’s a standard pattern for towns in the Eje Cafetero like Filandia, so let’s get the infrastructure stuff out of the way right off the bat. Here’s a map I got at La Casa de la Cultura (= The Culture House), on the southeast corner of the town square:

You’ll notice the primary importance of the plaza, the central square of town, with the church on one side and arcaded buildings filling out the other three sides. The Casa has an architectural model of it and a fanciful non-scale model, as well:

It’s half a world away from Italy but there’s a remarkable similarity to the hill towns of Tuscany. I suppose it’s not difficult to figure out that building things on top of a hill rather than at its base makes good sense for all kinds of reasons. You get a good view, you don’t get flooded when heavy rains come and you can use the bottom ground of the valley to grow stuff for the kitchen. Most historical towns of the Coffee Triangle are situated on hills, some of them at considerable altitude, so why shouldn’t they have the same town layout? After all, they were all built by folk who moved down from Antioquia, the department to the north where Medellín lies. The forebears of the people native to the Coffee Triangle were all “paisas,” the word used as a demonym for people from Antioquia and today from the Coffee Triangle, as well. It’s all part of a single cultural landscape. On the second floor of the Casa de la Cultura is an exhibition of old photographs of people from Filandia. They look distinctly European, as this montage shows very clearly:

There’s a lot of talk these days about the indigenous people of the area, the Quimbaya, but there’s absolutely no evidence of them anywhere. Colombia’s few remaining native peoples are tucked away in small enclaves well out of sight. During my visit to Filandia I saw only one native woman sitting on a doorstep making bead necklaces of immensely intricate and lovely design. She never looked up from her work as the tourists streamed past her. I stopped and said to her (in Spanish), “What beautiful designs!” She flashed a brief smile at me but said nothing. So the emphasis I heard from the shopkeepers selling the trendy handmade crafts about the link to Quimbaya culture in the area rang entirely false to my ears. There’s no physical evidence of the Quimbaya in the town save for a small cabinet in the Casa de la Cultura holding some pottery pieces of Quimbaya origin, all of them without date or provenance. I wasn’t buying it when one shopkeeper told me about Quimbaya influence on modern arts and crafts of the town. The Quimbaya were decimated by the European colonists and they’ve all but disappeared. The current spin on the blending of Quimbaya and colonial Spanish culture is a nice idea but remains just that: an idea. It was never a reality. A look at the historical photos of Filandia make that quite clear. There’s not an indigenous face among them.

What Filandia is today resembles the theme towns you find in the States. A good example is Leavenworth in my own neck of the woods in Washington State. Here’s the story from the Wikipedia page (here):

In 1962, the Project LIFE (Leavenworth Improvement For Everyone) Committee was formed in partnership with the University of Washington to investigate strategies to revitalize the struggling logging town. The theme town idea was created by two Seattle businessmen, Ted Price and Bob Rodgers, who had bought a failing cafe on Highway 2 in 1960. Price was chair of the Project LIFE tourism subcommittee, and in 1965 the pair led a trip to a Danish-themed town, Solvang, California, to build support for the idea. The first building to be remodeled in the Bavarian style was the Chikamin Hotel, which owner Jamie Peterson renamed the Edelweiss after the state flower of Bavaria.

Leavenworth is home to the Leavenworth Nutcracker Museum, which opened in 1995 and contains more than 5,000 nutcrackers dating from prehistoric to modern.[7] Leavenworth hosts an annual Oktoberfest celebration.[8]Leavenworth’s transformation into a theme town was inspired, and assisted, by Solvang, California. Later, the Washington town of Winthrop followed Leavenworth’s example and adopted a Western town theme.[9]

In November 2007, Good Morning America went to Leavenworth for Holiday Gifts for the Globe where GMA helped light up the town for the Christmas Holiday. Leavenworth was also named the Ultimate Holiday Town USA by A&E.

Filandia differs in that its historical underpinnings are real. But they belong decidedly to the past. Only a few old people remain who can make the basketry associated with coffee cultivation. The town has become a museum piece. It’s all very well for us tourists who spend a day there and then go back to the city, but I can’t imagine what it must be like to live there. I’d feel I was stuck in a period re-enactment from which there was no escape.

But as I said, it’s all very lovely. So let’s ditch the history and sociology and get to the pics, shall we?

I’m not sure who the chap on the plinth in the center of the square is. After catching sight of that ravishing purple shrub all thoughts of tribute to human accomplishment evaporated. I have no idea what the botanical name of that shrub is, but I’ll do my best to find out. It’s a new love of my life. I go weak in the knees when I’m around it. Equally jaunty and heartening is the lemon-yellow hibiscus that’s so popular here as an ornamental. I see it everywhere, always the same bright lemony color, unlike the hibiscus we have in the States that come in different colors. Lemon yellow is the choice in the Coffee Triangle and a good choice it is, that can’t be gainsaid. From the intense color you expect the blossoms to give off a citrusy fragrance — but of course they don’t. They’re true to their species, after all.

The church is adequately imposing to fulfill its function in the architecture of the square. It looks nice from the outside, although the metal sheeting covering the domes has the look of the galvanized aluminum used in the States for roof gutters, which (unfortunately) lends the church a rather Home Depot kind of air that by right it shouldn’t have. I’m as ardent a devotee of ecclesiastical architecture as you may hope to find but I put that part of me on hold when I came to Colombia. You don’t head into the colonies expecting to see the same things you see in the mother countries, that would be massively unfair. I don’t expect the church in Filandia to wow me architecturally as I am wowed by the cathedrals of Toledo or Burgos, for example. That said, nothing prepared me for the interior of Filandia’s church. It has everything in the way of atmosphere a church should have — candles flickering at the votive altars, statues of saints in holy repose or enacting something of mystical significance. But when I walked in, sat down in a pew and looked around, I thought to myself, “OMG it looks a public bathhouse in Budapest.” My momma did raise me right, but the eye will not be deceived:

Before my big mouth gets me any deeper into hot water let’s move on to the town itself, which is thoroughly charming. The hallmark of Coffee Triangle towns is their gaily colored houses sporting handsome balconies. The more whimsical the color scheme the better, much like some towns in Brazil that look like a paint truck overturned in the middle of the main street and splashed everything into a technicolor wonderment. For tourists with an insufficiently vivacious eye for detail the charms will fail to register. The detail requires attention, which people walking by looking at their cell phones supply in regrettably small quantity. If you really want to appreciate the domestic architecture of such towns you need to LOOK at it carefully. So let’s do our tourist duty and have a good gander at some of the houses. They’re really lovely:

If my friend and I had come into town on the back road rather than from the main highway, we would have seen this sign and all would have been revealed:

It means “Route of the Master Artisans.” Filandia is the eastern endpoint of the route, so that may well explain why the sign is on the west side of town, but everybody comes in from the main highway a few kilometers to the east, so somebody needs to start thinking outside the box and move the sign so all the tourist traffic coming into town from the main road passes it. Had I seen it when coming into town I’d have known much better what to expect; craft boutiques. I went through a ton of them and learned all sorts of things.

At one artisanal shop a young man was selling regional coffees — none from Filandia, by the way, they were all from elsewhere nearby in Quindío or Valle del Cauca departments. He was a wealth of information and I took advantage of the opportunity to pick his brains about the coffee business as it currently operates. It’s going full-bore boutiquey, no doubt about it. Some coffee farms in Quindío are now marketing their beans as a specialized local type, much the same as wine in France from certain areas is under appellation d’origine contrôlée, meaning it has to come from within the boundaries of a specific geographical area in order to be labelled with a name specific to that region. It even goes so far these days that some farms market their coffee as an exclusive product, just like the venerable Chateau Margaux in Burgundy does with its wine. You don’t shell out for Chateau Margaux — a cool $680 a bottle for a 2015 vintage years away from its peak — unless you’re sure it’s from that exact vineyard. I certainly hope to pass the rest of my natural lifetime without seeing boutique coffee reach $680 per lb.

The prices for the fancy boutique coffees didn’t strike me as exorbitant since I’m used to paying handsomely for Colombian Supremo in the States. But it’s way beyond the means of most Colombians. I made so bold as to mention that fact to the young man in the shop with the comment that Colombians mostly drink “tinto,” coffee made with poor-quality beans and sugar water. It’s the real thing but about as exciting as Nescafe. He quickly agreed that Colombians have only recently begun to enjoy the fruits of their own labors rather than exporting the best and drinking the rest. I hope that trend continues. The people of Colombia deserve to enjoy what their own land provides to the rest of the world so abundantly.

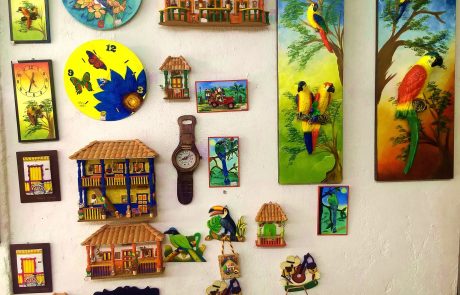

After the coffee talk (we were talking amongst ourselves without Linda Richman, she was too verklempt LOL) my friend and I started serious boutique cruising. In one shop, out the other, around and around we went, looking at a plethora of handmade articles from jewelry to natural cosmetics to straw hats banded gaily with bright colors and tons of other stuff. Pictures are better than words, so here you go:

I’ve been called a lot of things in my time but never a shopaholic, so I was very proud of myself for lasting a full two hours before I caved and headed for the nearest cafe to restore my fading powers. I had two especially interesting conversations with shopkeepers. One was a jeweller who used natural stones in her work. Quindío apparently has some emerald mines, a fact of which I was grossly ignorant, so the jeweller showed me a piece of matrix from one of the working mines with a small emerald embedded in it. They’re tiny things, not like the stones from Brazil that sometimes reach the size of eggs. Very clear, very beautiful stones that seemed to me difficult to set to good advantage because of their small size. The other stones in the jeweller’s work come from other Latin American countries — Brazil primarily, of course, because it has precious and semi-precious stones coming out the wazoo. I liked both the jewller and her work — there were some lovely pieces among what I saw.

The second chat was with a young woman who was the spit and image of the kind of person I’d seen in the many craft shops of Cannon Beach, Oregon barely a month earlier. Baggy sleeveless Indian gauze dress, Birckenstocks, tattoos on both arms, a braid down her back, sweet as the day is long and anxious to explain in great detail the mystical significance of Quimbaya ceremonial practices and iconography. I learned a lot from her and bought one of her talismans that’s supposed to put your luck in tip-top shape when you rub it between the palms of your hands. We could all use a bit of help in the luck department now and again, right? So for a tidy $3 I got fixed up with exactly the right tool to keep my luck at the top of its game.

If you’ve read more than one of my travel posts you’ll know without my telling you that any special plant friend that turns up in the proceedings is going to get a pic and some gushing. In the course of my boutique wanderings I came across a delicious Mexican Trumpet Vine in vibrant yellow. I got all tingly up and down the spine, which was the only appropriate response before such a handsome specimen. It happened to be positioned in front a striking mural so art receives its due as well as botany. There’s the magic of synergy for you . 🙂

In addition to the Casa de la Cultura there’s a museum in town, just off the southwest end of the main plaza, dedicated to the art of basketry. In the old days coffee cultivation required the use of several different kinds of baskets – some for harvest, some for processing, some for transport. The fine art of making these baskets in their many sizes is all but extinct, so the museum is a look into the past, not a reflection of the present. It’s a beautifully done museum, to the point that its creation must have been contracted out to somebody in the national Department of Tourism responsible for museum development. Everything looked top-drawer professional and state-of-the-art with regard to exhibition structure and presentation. Such a display in the little town of Filandia leads me to suspect that somebody in the mayor’s office is very deft at writing grants. Good on ya, boys (or gals, as the case may be). The result is excellent.

I mentioned our guide earlier — he of the blonde highlights, the two earrings and the I Heart New York T-shirt. He talked a mile a minute but I got it all. To be perfectly honest, the rapid-fire explanation of the different sizes of basket and their uses was a bit much of a muchness. We all know what a basket is and that it can be used for a variety of things. What fascinated me most was learning what plants were used as raw material. One of them is the selfsame philodendron we grow so happily as a houseplant in the States. Another one is in the grass family (Poaceae). The one that made my eyebrows shoot up is a woody shrub in the nettle family (Urticaceae), of all things. Whoda thunk that the botanical family that produces something to be avoided in my neck of the woods (stinging nettles) would provide a basic material for an entire handicraft tradition in another part of the world? Let it remind us of the wondrous variety in Nature. It’s always got a punch line up its sleeve, as I discovered wandering among the baskets in Filandia. Here are a few pics:

If you held me at gunpoint and demanded the REAL reason I went to Filandia I would stammer out some story about wanting to be out in the countryside and see the landscape. So there’s the naked truth of the matter. I was more than content doing the tourist thing, but what I wanted most from Filandia was an experience of its surroundings. And I got my druthers, indeed I did. At one point while I stood at a viewpoint on the edge of town looking out over the scenery I thought to myself, “Goodness sake, I could be fooled into thinking I’m in Gloucestershire.” It’s a remarkably tamed landscape, many of the fields obviously given over to pasture for animals rather than cultivation. All the same, it’s landscape and very beautiful in its green relaxation. Better to show the pics that run on about it:

The colored tree in the first pic of the second row deserves special mention. I first saw it in La Florida. When I wrote the post about La Florida I didn’t know anything about the tree that dotted the hillsides with spots of light color. Now I’m in the know, so here’s the skinny. The species is Cecropia peltata, known locally here in the Coffee Triangle as “yarumo blanco.” The Wikipedia page on the species is here. While doing research I came across it in a listing of invasive species — “oh no, Mr. Bill, please not an invasive species …” I thought to myself. Further investigation showed that classification to be alarmist so I discarded it without a moment’s hesitation. I consider the species a thoroughly respectable neotropical tree just like the USDA does in its fact sheet. Why should I argue with the pros? I was astonished to learn that it’s in the nettle family (Urticaceae), just like the plant I mentioned earlier used for basketry. I had no idea that nettles could be up to so many things useful to us humans. My entire conception of the botanical family has had to undergo radical change to clear it of prejudice born of my experience in the Bitter North. The word “nettle” is not warm and fuzzy where I come from.

An interesting side note about the genus Cecropia: it’s the favorite comfort food of South American sloths. Go figure. So the next time you’re out stomping in the woods in the Pacific Northwest as I’m wont to do and you come across a patch of stinging nettles, remember that somewhere in the world some slow-motion, furry creature is munching with utmost delight on the leaves of a relative of what’s ready to bring out red welts on your skin if you touch it. It just goes to show that we must never underestimate Mother Nature. She’s got more stuff figured out than we’ll ever manage to do in a million years.

The pics of the landscape come from the end of my visit to Filandia, when we left the town on the motorbike and headed out to view the countryside. As we passed through town to wend our way home I was reminded of a striking painting I saw in the Casa de la Cultura. Here it is:

What is Don Quixote doing in an open, hilly landscape with a lone Cecropia peltata facing him? I think what we have on our hands is a case of self-irony. Does the artist consider the people from Antioquia who moved down south, colonized the Coffee Triangle area and turned it into what it is today to be Quixotes? — without the windmills, one should add, since there’s not a windmill in sight anywhere in the region. It was certainly a challenging proposition they engaged, as all colonization is. Were they tilting at windmills? Did they believe their experiment a folly of the kind we know Don Quixote’s battles to be? From my perspective the human figure in the picture should be the cafetero, the coffee farmer. He and his tribe were the ones who changed the Coffee Triangle into its current state of agricultural submission à l‘anglaise. The change factor was backbreaking work, not tilting at windmills.

But humans are always dependent on the natural environment no matter how much they alter it. That’s as basic a fact of human existence as you can find. So let’s change our focus and take as the central figure of the painting the tree, our dear Cecropia peltata. Its bicolored leaves tell a better story — what was once one thing has become another. That’s the story Filandia still tells even as we speak.