May 2019

My personal history with organ music goes back almost 50 years. When I was in high school in a rural town of 1,500 in the boondocks of the Pacific Northwest I wrote a letter in German to the organist of the cathedral in Schleswig, Germany (St.-Petri-Dom zu Schleswig) because I was so enthralled with a recording I’d bought of Bach organ works played on the Marcussen organ there. Lo and behold I got an answer from the cathedral organist with a postcard of the organ and a friendly greeting. That happened long before the days of the Internet that allows me today to get full information on the organ from the cathedral’s German Wikipedia page. I was an organ neophyte then and I’d have been hard-pressed to tell a Marcussen from a Flentrop. But even in my rural backwater in the USA in the 1970’s I was on the trail of the German Orgelbewegung, the return to historical construction practices that began in Europe in the 20th century and continues to this day, following the principles used by 17th and 18th century builders to fashion modern instruments as splendid sonically as are the historical organs still in existence throughout Europe. Here’s some information on the Schleswig instrument from the German Wikipedia page (here):

My personal history with organ music goes back almost 50 years. When I was in high school in a rural town of 1,500 in the boondocks of the Pacific Northwest I wrote a letter in German to the organist of the cathedral in Schleswig, Germany (St.-Petri-Dom zu Schleswig) because I was so enthralled with a recording I’d bought of Bach organ works played on the Marcussen organ there. Lo and behold I got an answer from the cathedral organist with a postcard of the organ and a friendly greeting. That happened long before the days of the Internet that allows me today to get full information on the organ from the cathedral’s German Wikipedia page. I was an organ neophyte then and I’d have been hard-pressed to tell a Marcussen from a Flentrop. But even in my rural backwater in the USA in the 1970’s I was on the trail of the German Orgelbewegung, the return to historical construction practices that began in Europe in the 20th century and continues to this day, following the principles used by 17th and 18th century builders to fashion modern instruments as splendid sonically as are the historical organs still in existence throughout Europe. Here’s some information on the Schleswig instrument from the German Wikipedia page (here):

Weitere teure Reparaturen in den 1950er Jahren führten schließlich zu einem notwendigen Neubau 1963 durch die Firma Marcussen (III/P/51). Dabei wurde der heutige Hauptwerk-Prospekt in der Form von 1701 wiederhergestellt, während das Rückpositiv neu entworfen wurde. Das geschaffene Werk war mit seinen vielen Mixturen und farbigen Zungenstimmen in allen Werken eine Neobarockorgel der niederdeutschen Orgellandschaft. Das Werk zeichnete sich durch eine solide Bauweise und qualitätvolle Materialien aus; einige Register sind aus Kupfer gefertigt.

[Additional expensive repairs in the 1950’s finally led to the necessity of a new construction in 1963 by the Marcussen Company (3 manuals, pedal, 51 stops). The original Hauptwerk case from 1701 was reconstructed while the Ruckpositiv was based on a new design. The finished instrument with its many mixtures and colorful reed stops across all divisions represents a neo-Baroque organ of the Low German organ landscape. The instrument excels through its solid construction and high-quality materials; some stops are made of copper.]

Here’s a pic:

Marcussen organs are fantastic and this is a fine example of their work. The list of good European builders is long — Flentrop (one of the venerables like Marcussen), Klais, Schwenkedel, Führer, Schuke, Rieger, Ahrend, Metzler … and then there are the Americans who’ve jumped on the Orgelbewegung bandwagon to excellent effect, for example Taylor & Boody who in 1985 built the exquisite organ in the College of the Holy Cross in Worcester, Massachusetts, surely one of the most significant American instruments of the 20th century.

As for the music played on these lovely instruments, a lot of it comes from the Big Boys, of course — the names we all know so well, foremost among them J.S. You Know Who. Starts with “B,” rhymes with rock. I’ve gone off at the mouth in other music posts about my fraught relationship with You Know Who so I’ll stifle myself here. He was obviously a Big Deal as far as organ literature is concerned, just as Buxtehude was, for whom I harbor the greatest fondness. Both composers wrote all kinds of other stuff, too, but still they dominate the world of organ music. So I’m taking a completely different tack in this post and putting my focus on composers who are not at all as well known but who IMHO should be. My point is to draw attention to their accomplishments and to promote their music to lovers of organ music in the hope that they’ll become favorites as they are for me. I won’t even bother to alphabetize them, I’ll just plop them down in the order I find them in my collection. Let’s get started.

![]()

Francisco Correa de Arauxo (Spanish, 1584-1654)

From his dates you’d place him in the early Baroque period but you’d be wrong. He’s as Renaissance as they come, is Correa. In the interest of transparency I should make plain that Correa is one of my favorite composers of all time. Not only have I avidly collected recordings of his music, when I lived in Germany lo these many decades ago I ordered from Spain both volumes of his Facultad Orgánica in the edition by Santiago Kastner. The bookshop in the small town where I lived thought I was a few sandwiches short of a picnic, but never mind. I got my two volumes from Spain in the end and that’s all that mattered. They’ve stayed with me over the past 40 years as one of my prized possessions.

For all his musical gifts Correa appears to have been rather a thorny character, as the Wikipedia page on him (here) reveals:

Correa de Araujo was born in Seville. Like most Spanish organists from this era, details of his life are clouded by obscurity. For some time even the years of his birth and death were disputed.[1] His musical background is unclear; he claimed to have learned theory by studying the works of Francisco de Peraza and Diego del Castillo. In 1599 he received an organ appointment in Seville, but became embroiled in a lawsuit with rival Juan Picafort, which delayed confirmation of this appointment for six years. In 1608, he was ordained as a priest. He maintained the post at Seville until 1636. Several times he applied unsuccessfully for other positions, and once again in 1630, he became embroiled in lawsuits which culminated in a brief period of imprisonment. In 1636, he left Seville and took up a post at Jaén Cathedral. In 1640, he was appointed as a prebendary at Segovia Cathedral, and remained there for the last fourteen years of his life. He died at Segovia in abject poverty.

So, a thoroughly litigious creature, it seems … perhaps the strictness of his counterpoint has something to do with a mind sharpened on the finer points of the law, who can say? There’s a new edition of the Facultad Orgánica edited by Miguel Bernal Ripoll and a description of it (here) supplies the following information:

La Facultad Orgánica es, sin duda, una de las obras para tecla más importantes publicada en España en todos los tiempos, con importantes aportaciones en el campo de la teoría musical, la práctica interpretativa, la didáctica, la teoría compositiva y la estética. Su autor, Francisco Correa de Arauxo (Sevilla, 1584 – Segovia, 1654) recoge la herencia de los grandes organistas del siglo XVI e incluye en su obra los nuevos recursos que ponía a su disposición el instrumento gracias a las innovaciones introducidas por los organeros principalmente flamencos. De este modo, el autor desarrolla nuevas formas de expresión apoyándose en la tradición hispana anterior.

[The Facultad Orgánica is without doubt one of the most important publications of keyboard works from Spain of all time, with significant contributions in the areas of musical theory, interpretative practice, didactics, compositional theory and esthetics. Its author, Francisco Correa de Arauxo (Sevilla, 1584 – Segovia, 1654) gathers together the legacy of the great organists of the 16th century and includes in his works the new resources available to him through developments in Iberian organbuilding introduced primarily by Flemish builders. In this way the composer developed new forms of expression while rooting himself in the Iberian traditions of the past.]

The Iberian organ is so different from those of the rest of Europe that it’s difficult to transfer the music to instruments of other organbuilding traditions. Things like divided stops — separate mechanisms for treble and bass of a single register — and in the later Baroque a mania for horizontal reed stops makes it a lackluster business to play much of Spanish organ literature on a northern European instrument. The tonal quality of flue stops in Spanish instruments is also quite different from that of instruments outside the Iberian Peninsula. The closest similarity is with the sound of Italian organs, but that applies only to flue stops, not to reeds. Consequently, if a recording of Correa’s music is not played on a Spanish instrument I won’t buy it, just as I wouldn’t go into a French restaurant and order pizza. Call me stubborn if you will, but that’s my story and I’m sticking to it.

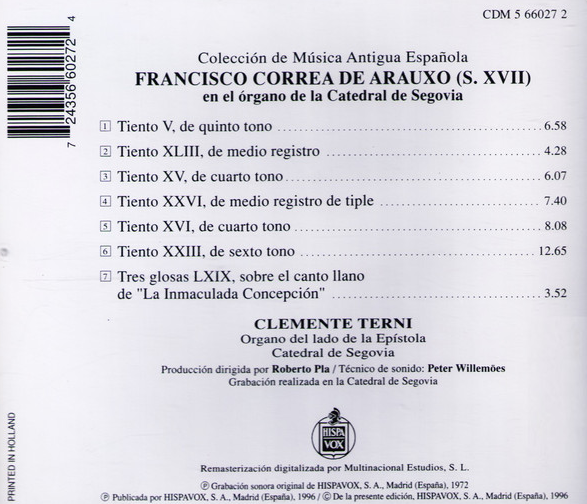

The best recording I have of Correa’s music is by the Italian organist Clemente Terni on the Epistle Organ of the Cathedral of Segovia, where Correa spent the last years of his life. It’s a fantastic organ built in 1702 by Pedro de Liborna Echevarría and offers the perfect instrument for Correa’s music despite a construction date some 50 years after Correa’s death. I’ve never found a recording I like better — or an organ better suited to breathing life into Correa’s compositions. Here’s a pic:

The horizontal reeds typical of Spanish organs of the later Baroque weren’t common in organ construction during Correa’s time so there’s no use of them in Terni’s performance. That’s a good thing, by the way. Horizontal trumpets are absolutely fabulous, don’t get me wrong, but not for Correa’s music. Terni’s recording is from 1971 but was reissued on the Hispavox label in 1996 and is still available. Here’s the verso:

Playing Correa’s music is completely unlike playing Bach or Buxtehude, where you basically just read what’s in front of you on the page and make sure it all hangs together. Performing tientos by Correa requires you to be like an actor taking on a role in a play — you have to get inside the character of the piece and play it from the inside out. Each piece has emotions running through it that shift and change within the space of a few bars, like feelings flitting across the face of an accomplished actor. You also have to speak the musical language of Correa’s time and place. So I take playing his music as serious business — the responsibility the music places on the performer is considerable. Having got inside of his music doubtless has something to do with my sense of attachment to him as an old and treasured friend. He’s been with me for over 40 years and will without doubt see me to the grave.

There are other recordings of Correa’s music to be had, among them the complete works performed by Andrés Cea Galán. He plays with perfect competence, although not IMHO with the deep and probing insight Terni brings to the task. There are some good performances on YouTube, as well, to give you a taste, such as the one by Luis Antonio González played on the fantastic historic organ in Daroca (here). You’ll find some of Cea Galán’s performances on YouTube, as well. His recording of Correa’s complete works on the organ of the Church of Santa Maria, Garrovillas de Alconétar (in the Spanish province of Cáceres) is available on the Brilliant Classics label. You can never have too much Correa in your collection, I think, so give it a listen.

![]()

Girolamo (Hieronimo) Cavazzoni (Italian, c. 1525 – after 1577)

I’d be surprised if you read the name above and didn’t think to yourself, “Who?” He’s not exactly a household name, although apparently he approached that status during his lifetime, about which we know very little, as the Wikipedia page on him (here) explains:

Practically nothing is known about Cavazzoni’s life. The approximate year of his birth can be surmised from his remarks in the preface to Intavolatura libro primo, the first collection of his music to be published. The volume was printed in Venice in 1543, and Cavazzoni informs the reader in the preface that he is “not much more than a boy” (anchor quasi fanciullo), which indicates Cavazzoni was around 17 at the time. Cavazzoni’s reputation must have been considerably high already at that time, since he was able to secure a privilege from the Venetian council to publish this collection. The second collection of Cavazzoni’s music, Intabulatura d’organo, carries no publication date (it appeared somewhere between 1543 and 1549) and contains no biographical details.

By 1552 Cavazzoni may have been working in Urbino, and from 1565 to 1566 he supervised the building of the organ in the court church of S Barbara in Mantua. The composer was apparently on good terms with Guglielmo X Gonzaga, Duke of Mantua, and worked as organist at S Barbara. The last known mention of Cavazzoni is from 1577, naming him as organist of that church.

The organ of which Cavazzoni supervised the construction is not just any old organ, which Wikipedia astonishingly fails to note. It’s a major work by Graziadio Antegnati, the Italian equivalent of Arp Schnitger in Germany, which is to say: Big Deal. There aren’t that many Antegnati organs in original condition left on the Planet, so having the one in Mantua makes of Sta Barbara an organological pilgrimage site. Here’s a pic:

I own two recordings of Cavazzoni’s music, volumes one and two of a performance by Sergio Vartolo of the complete Intavolatura cioe recercari, canzoni, himni, magnificat published between 1543 and 1549. They’re on the Tactus label and still available. In the recording of volume one Vartolo plays the historic Antegnati organ in San Giuseppe in Brescia. For volume two he uses the organ built between 1471 and 1475 by Lorenzo da Prato in San Petronio in Bologna — a building so huge that it has what seems to be 10 seconds of reverberation. Absolutely cavernous.

I also own a recording of the complete works by Cavazzoni’s father, Marco Antonio, performed by that Netherlandish conundrum Liuwe Tamminga, who’s been a titular organist at San Petronio in Bologna for donkey’s years. He, too, plays the Lorenzo da Prato organ in San Petronio for the elder Cavazzoni’s works, to excellent effect I might add. The elder Cavazzoni’s music is quite athletic compared to his son’s more straight-laced style and receives a fitting rendition by Tamminga, who has a special affinity for Italian music of the Renaissance and a great talent for bringing it alive rhetorically. The recording was done in 2004 and is still available. Here are the recto and verso:

If I were you I’d keep it in the family and get both dad and sonny boy in the the same fell swoop. You won’t be sorry you did if you’re a fan of Italian organ sounds — the instruments are glorious.

![]()

Pablo Bruna (Spanish, 1611-1679)

When you consider Bruna’s dates and see how conservative his musical style is, you get an idea of just how slow things were to change on the Iberian Peninsula with regard to the development of the Baroque style. It wasn’t until the late Baroque that things really jumped on the Baroque bandwagon in the works of such composers as Juan Francés de Iribarren and José de Nebra, although when things finally got started they took off like rockets. With Bruna we’re still in the highly structured world of the Renaissance tiento, a strict contrapuntal form sometimes with an episodic structure. I include Bruna in the list because of his remarkable quality as a person and because of the sweetness of his music. He’s the Piero della Francesca of the organ, to pull an analogy from the world of painting.

Precious little is known of his life, as usual, and the Wikipedia page on him (here) is brief in the extreme:

[Bruna] was a Spanish composer and organist notable for his blindness (suffered after a childhood bout of smallpox), which resulted in his being known as “El ciego de Daroca” (“the blind man of Daroca”). It is not known how Bruna received his musical training, but in 1631 he was appointed organist of the collegiate church of St. María in his hometown of Daroca, later rising to choirmaster in 1674. He remained there until his death in 1679.

Thirty-two of Bruna’s organ works have survived, mostly in the tiento form. Many, known as tientos de medio registro, are for divided keyboard, a typical feature of Spanish organs. Bruna was known as a capable teacher and his nephew Diego Xaraba, whom he taught, also became a prominent musician.

I’m also fond of Bruna because he was active in Daroca. The organ in the town’s Collegiate Church is a jewel in the crown of Spanish organbuilding and as a teenager I bought a recording of Spanish music played on it by Francis Chapelet, a French organist who’s spent much of his adult life involved with Spanish organs and organ music. The sounds that came from the Daroca organ were unlike anything I’d ever heard before and I was instantly a devotee — have been all my life since. Here’s a pic of it:

Recordings of Bruna’s music are always anthologized with works by other composers — an oeuvre of 32 works is surely enough to have a few complete works CDs, but nobody’s gone there, more’s the pity. There are some CDs available with works by Bruna, but just to hear his music you can turn to YouTube. One of my favorites is the performance of Bruna’s Tiento de Segundo Tono por Ge sol re ut, sobre la Letanía de la Vírgen performed by the Spanish organist Santiago Banda on the historic organ of the Iglesia de los Padres Dominicos in Pamplona. Such a lovely piece of music. Wherever you can find Bruna’s music, grab it, you’ll find your ears thanking you profusely.

![]()

Abraham van den Kerckhoven (Flemish, c. 1618 – c. 1701)

Flemish organists were Big Deals in their day but unfortunately they’ve fallen off the table these days to a large degree. Kerckhoven should be much better known given the quality and quantity of his music. During my organ studies at university I worked on one of his Fantasias (D major) which uses the imitative structure so popular at the time, involving changes of manual to create a statement-response echo dynamic in the musical development of the piece. If you’re an organist you’re in luck because his complete works are available online from IMSLP (here) in the edition published by Monumenta Musicae Belgicae in 1933. For free, even. So go crazy.

The Wikipedia page on Kerckhoven (here) gives a brief description of his musical style:

Most of his works were found in 1905 in a hand-written volume of organ pieces dated 1741 and compiled by Jacobus Ignatius Josephus Cocquiel, organist and priest of Sint-Vincentiuskerk in Soignies. This manuscript is sometimes referred to as the Cocquiel manuscript and is currently in possession of the Bibliothèque Royale Albert I in Brussels, catalogue number Ms II 3326. Kerckhoven’s works were published for the first time in 1933 by J. Watelet as the second volume of the Monumenta musicae Belgicae series; in 1982 a facsimile of the Cocquiel manuscript was published with an introduction by Godelieve Spiessens, and this edition is commonly used now.

Kerckhoven’s surviving oeuvre consists mostly of organ pieces: fantasies, fugues, preludes, mass settings and other works. His music is influenced by Italian and French styles; fugues and fantasias are reminiscent of Johann Jakob Froberger and quite a few pieces contain typical French registration indications: pieces for plein-jeu, fantasies pour cornet, for cromorne or dessus de tierce. Sectional preludes with alternating free and imitative counterpoint, harmonically rich and expansive, are reminiscent of the northern German organ tradition.

If you download the score of his works from IMSLP you’ll find a lengthy biographical introduction and a detailed discussion of his musical style in both Dutch and French — no English, sorry. But hey, that’s why God made Google Translate, right?

Kerckhoven’s reputation has climbed enough in recent years to occasion a recording of his works by François Houtart in 2013 on the Pavane label. I’ve heard it but I don’t own it. The tracks of Kerckhoven’s I’m most fond of are ones I ripped from LPs on the Nonesuch label I bought when I was just a young thing. The vinyls are all long gone, I fear, so you’ll have to turn to M. Houbart’s performance to sample Kerckhoven’s music. You’ll discover a style unlike the organ music of other European traditions, one that has hints of Spanish and German and a bit of Italian, but ends up still being its own beast that makes a very different impression on both the ear and the emotions.

You can hear the Fantasia in d minor played by Joseph Ripka on YouTube here. It obviously owes a debt of gratitude to the Spanish tiento de medio registro — a solo tiento for treble or bass voice. That similarity should perhaps not surprise us since the Low Countries were ruled by the Spanish Crown from 1556 until 1714, which includes the entirely of Kerckhoven’s lifetime. There must have been considerable to-ing and fro-ing of musical things with Spain during those 158 years. A few tientos must surely have made their way northward and landed in the ears of a few Flemish organists. In any case, Kerckhoven’s music is fab and I’m a huge fan — especially because he helped me get an A in that organ performance class. 😉

![]()

Tarquinio Merula (Italian, 1595–1665)

Back to Italy we go, this time for Merula, whose organ music is like fireworks. We’re in luck with regard to recordings, too, because Francesco Cera has performed Merula’s complete works on the organ of San Michele in Bosca in Bologna. The CD is available on Amazon and you can even stream it if you have the Amazon app and your subscription is paid up. The Amazon page for it is here. As luck would have it you can get the entire keyboard output of Merula online at IMSLP (here) so you can play it yourself or follow along from the score while listening to the recording.

The biographical information on Merula (here) is not of a happy life, albeit a very productive one:

He was born in Busseto. He probably received early musical training in Cremona, where he was first employed as an organist. In 1616 he took a position as organist at the church of S Maria Incoronata in Lodi, where he remained until 1621, at which time he went to Warsaw, Poland to work as an organist at the court of Sigismund III Vasa.

In 1626 he returned to Cremona, and in 1627 became maestro di cappella at the cathedral there, but he only remained for four years, moving to Bergamo to accept a similar position in 1631. Alessandro Grandi, his predecessor, had died in the Italian plague of 1629–31 (which affected many cities in northern Italy, including Venice), and he faced the formidable task of rebuilding the musical institution there after many of its members had died.

Unfortunately Merula got into trouble with some of his students, and was charged with indecency; he chose to return to Cremona, where he remained until 1635. During this period in his life he seems to have had numerous troubles with his employers, possibly of his own making; after fighting with the administrators at Cremona over a variety of issues, he returned to Bergamo, serving this time at a different church, but was disallowed from using any musicians from his former place of employment. In 1646 he went back to Cremona for the final time, serving as maestro di cappella at the Laudi della Madonna until his death in 1665.

Let’s leave aside his troubled life story and just concentrate on the music. There’s a reason he’s considered a Big Deal by those in the know — by which I mean those with a speciality in early Baroque Italian music. I’ve included Merula because of his importance in the history of organ music although most of the music he wrote was in other forms — madrigals, sacred vocal music a la Monteverdi, instrumental canzonas, you name it, he was all over the place. Merula adopted for his organ music stylistic elements infiltrating instrumental music from the stile moderno or seconda prattica, which of course got its start in Venice. His music is wonderfully innovative and imaginative, nothing stick-in-the-mud Renaissance about it at all. That’s why he strikes me as so important a composer for the organ.

Cera’s performance of Merula’s music is scintillating and the organ of San Michele in Bosco in Bologna he uses for the recording is a delight. It was built in 1526 by Giovanni Battista Facchetti and has a wonderful range of both principal and flute stops. Really good flute stops are atypical for an Italian organ of that period so the organ of San Michele is a special treat. Its wide palette of tonal resources allows Cera to bring out the surprise in Merula’s music, enabling the registrations to sculpt off the page Merula’s sprightly and innovative music. Big thumbs up. If you get only one CD of early Italian organ music, let this be the one.

![]()

Jean-Nicolas Geoffroy (French, 1633–1694)

When we listen to organ music on a CD it’s dissociated from the environment for which the music was intended because organ music in most cases (especially French cases) has a liturgical function. Organ music intended purely for concert performance didn’t really start until the 19th century. French organ music, structured and conditioned at every turn by the Catholic liturgy as it is, is especially dependent on alternatim practice, with relatively short organ pieces coming before or after a plainchant or choral verse and dependent in good part for their effect on the contrast with the unaccompanied vocal element.

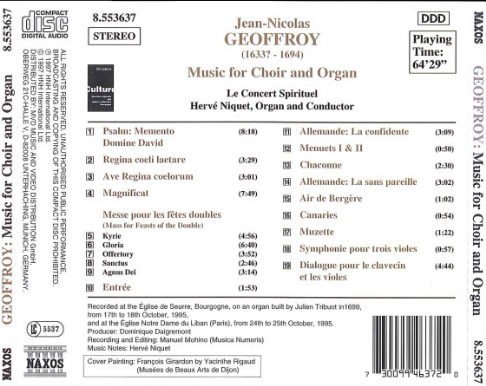

Paul McCreesh has become famous for his re-enactments of liturgical contexts for musical performances of Baroque music from Germany and Italy. Hervé Niquet, the director of the superlative group Le Concert Spirituel, does the same thing for French organ repertoire in this recording of music by Jean-Nicolas Geoffroy. The fine singing of Le Concert Spirituel combines with Niquet’s playing on the organ of the Eglise Saint Martin de Seurre, Bourgogne, on an organ built by Julien Tribout in 1699. It’s a gorgeous thing with a gorgeous sound. Here’s a pic:

Who was Geoffroy? He’s certainly not among the household names of French organ music like Louis Marchand, Nicolas de Grigny or Couperin. There’s next to no information on his life beyond some of his activity in Paris and his move to Perpignan, down near the Spanish border, toward the end of his life where he held his last post at the Cathedral, as the Wikipedia page on him (here) explains:

His life before 1690 is unknown; he was probably a pupil of Nicolas Lebègue and served as titular organist of the Saint-Nicolas-du-Chardonnet church in Paris. He was considered an expert in organ building and at some point in life settled in Perpignan where he played the organ of Perpignan Cathedral (Cathédrale Saint-Jean-Baptiste)

Being a student of Lebègue would explain why he was such a good composer, since Lebègue was one of the most famous organists of Paris. His pupils included Nicolas de Grigny and Pierre d’Agincourt, both big names in French organ music of the period. Given the inventiveness and quality of Geoffroy’s music I can see why Niquet selected him for the liturgical re-enactment of a service. The effect is fabulous. Here’s the verso of the CD, on the Naxos label and still available on Amazon:

![]()

Andreas Kneller (1649-1724)

Kneller’s biography has several layers we need to peel off from each other like the rings of an onion. Here’s the info from his Wikipedia page (here):

Born in Lübeck, he was the younger brother of portrait painter Sir Godfrey Kneller. Nothing certain is known about his musical education, though he may have learnt from Franz Tunder (1614-1667), organist of St. Mary’s Church, Lübeck, or his own uncle Matthias Weckmann (ca. 1616-1674), organist of St. Jacob’s Church, Hamburg. In 1667, he became organist of the Marktkirche in Hanover, succeeding Melchior Schildt (1592-1667). In 1685, he moved to Hamburg, where he became organist of the Petrikirche. It was there that he made the acquaintance of Johann Adam Reincken; he went on to marry his daughter Margaretha Maria in 1686. Kneller’s son-in-law Johann Jacob Hencke became his assistant in 1717, and succeeded in him in 1723. Kneller was well respected as a musician, and often acted as an examiner of organs and organists. He was part of the group that examined the candidates for organist at the Jacobikirche, Hamburg, in 1720, which included J.S. Bach (though he did not appear for an audition, he was still chosen for the post but had to decline).

Goodness sake, talk about name-dropping … Big brother was, as Wikipedia styles it, “the leading portrait painter in England during the late 17th and early 18th centuries, and was court painter to English and British monarchs from Charles II to George I.” He was also elevated to the aristocracy in 1715, becoming Sir Godfrey Kneller, 1st Baronet. Not too shabby for a kid from Lübeck, although he got the title from George I, who was as German as Weißwurst and didn’t even speak English, so there you have it — birds of a feather etc. etc. And while we have for centuries heard very little indeed about his little brother Andreas it obviously isn’t because of the company he kept. His uncle was Matthias Weckmann, one of the major figures of North German organ music of the period. Studies with Franz Tunder? Another of the biggies in the North German music scene. And after getting chummy with Johann Adam Reincken he proposed to the latter’s daughter, which was usually standard practice only if you got the dad’s job, so obviously there was some clout at work there, too. The Jakobikirche in Hamburg happens to house one of the most famous organs by Arp Schnitger, the rockstar of 18th century North German organbuilding. Here’s a pic of it:

By the way, those big pipes in the side towers are 32 feet long, oh yes they are. So it’s no wonder the Jakobikirche Schnitger is a Big Deal. If you were packing something 32 feet long in each holster it would probably go to your head, too, right? Just nod yes, I won’t believe anything else from you.

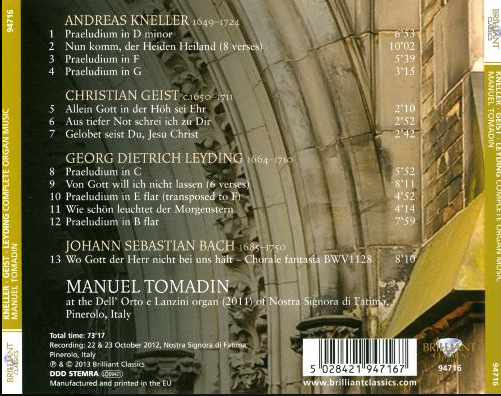

So in his own time and context it’s clear that Kneller was a Big Deal. Does his music show it? I think it does, and we can judge these days because there’s more than one recording of his complete works. The one I own is by Manuel Tomadin, an Italian organist who appears to be everywhere and to play absolutely everything, much like Simone Stella, another Italian organist who I think may be the Energizer Bunny in disguise to judge from his concert and recording schedule. Tomadin’s recording includes the complete works of three little-known German composers. Here’s the CD verso:

When I see somebody recording North German music on an Italian organ I immediately break out in a cold sweat because an Italian organ of the Renaissance or Baroque period has nothing — and I mean NOTHING — to do with a North German instrument. But fear not, the Orto e Lanzini organ at the Basilica of our Lady of Fatima in Pinerolo is a Schnitger knock-off, so it’s all good. Detailed information on the organ is available (in Italian) on the builder’s website (here). Here’s a pic:

Compare that to the pic of the Schnitger in the Jakobikirche and you’ll see that somebody’s been pilfering ideas from somewhere north of the Alps … But it’s all good and the organ sounds great on Tomadin’s recording. It’s on the Brilliant Classics label, which is the go-to label for classical music that’s both good in quality and easy on the wallet. I own tons of Brilliant Classics titles and love them to death. They’d still be cheap at twice the price.

Since we’ve mentioned Kneller’s father-in-law Johann Adam Reincken, I want to put in a plug for his organ music, too, because it’s fantastic. Reincken was actually Dutch, born in Deventer, and went to Hamburg in 1654 to study with Heinrich Scheidemann, one of the bigwigs of the organ scene at the time and an important composer. When Scheidemann died Reincken took over his position at the Catharinenkirche in Hamburg and married one of Scheidemann’s daughters — which was part of the gig, believe it or not. Buxtehude had to do the same thing when he got his job at the Marienkirche in Lübeck. Speaking personally, that convention would’ve sucked the idea of going into church music out of my head like a 1 HP shop vac, but we all have different threshold levels, don’t we. In any case, Reincken wrote among other things one of the most astonishing chorale fantasias I’ve ever heard, on the hymn “An Wasserflüssen Babylon” (= By the Waters of Babylon). There’s a story about that piece involving You Know Who, so let’s get the skinny from Reincken’s Wikipedia page (here):

Reincken died wealthy. In his lifetime he was heralded as one of the best organists in Germany; he knew Dieterich Buxtehude closely and influenced Vincent Lübeck and Johann Sebastian Bach. The latter may have met him; a well-known apocryphal anecdote describes how Reincken and Bach met, and how, after Bach improvised a lengthy fantasia on the Lutheran chorale “An Wasserflüssen Babylon” (paying homage to Reincken’s massive fantasia on the same chorale), Reincken remarked: “I thought that this art was dead, but I see that it lives in you.” Christoph Wolff adds as a further detail of this visit by Bach to Hamburg in 1720, that on that occasion he performed the organ fugue BWV 542, the theme of which is based on a Dutch popular tune (called ‘Ik ben gegroet van…’), presumably as an homage to Reincken’s Dutch origin. At any rate, Bach was evidently deeply impressed by Reincken’s music, arranging several of the works from Hortus musicus (as BWV 954, 965 and 966). In 2006, the earliest known Bach autograph was discovered in Weimar: a copy of Reincken’s An Wasserflüssen Babylon, which Bach made for his then teacher Georg Böhm in Lüneburg in 1700.

So for all you guys who think You Know Who is the be all and end all of organ music, there’s me throwing you a bone in a post that has declined to include him in the list. Feel better? Good, glad to hear it. Far be it from me to provoke an outbreak of grumpiness through depriving somebody of their fix of You Know Who.

You can choose among several performances of Reincken’s fantasia on YouTube. My favorite is a performance on the selfsame Schnitger in the Jakobikirche in Hamburg we just examined, with someone singing the hymn to instrumental accompaniment before the fantasia begins. It’s one of the loveliest hymntunes I know. The YouTube link is here.

Another by the way: you find Vincent Lübeck mentioned in the citation above and he should actually have his own entry in this list, but I’ve gone on long enough already. One of my favorite organ pieces is his prelude and fugue in E major. There’s a fantastic performance of it by Maria-Magdalena Kaczor on YouTube (part 1 here). She plays the Muhleisen organ (1983) of the Eglise des Billettes, a Lutheran (!) church in Paris. Here’s a pic:

The video shows her playing at the console so you can see her fingers and feet flying while she rips through the piece. She’s the Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez of the current organ scene. Don’t hate her ’cause you ain’t her. 🙂 And trust me, while you watch her and hear her rendition of that wonderfully athletic work the last thing on your mind will be #WheresMitch.

![]()

So, there we have it. I could go on for at least twice the length of this post — composers keep popping into mind. But I’ll cease and desist and come back for a second installment if the urge overcomes me to shove more names your way. In the meantime, enjoy!