March 2018

Mountains have been very much in my mind lately as I plan trips to visit montane areas here on the islands of Panay and Negros in PH. There are fantastic mountain ranges on both islands, and since I’ve been a mountain-dweller from my tenderest years they always draw me more than the beach scene. People I meet always say, “Oh sir, you need to go to Boracay!” Do I indeed? Does it really make good sense to take my chalk-white body to a beach, strip it down and expose it to massive quantities of UV radiation? (To say nothing of the problematic aesthetics of my swanning about in swimtrunks …) My dermatologist tells me the idea is flawed from the get go. I’m inclined to take her word for it.

Pend Oreille Lake, Sandpoint, Idaho

The mountain landscape of my home area in the Pacific Northwest of the United States bears scant resemblance to the mountains here, but when I go to the mountains in PH I always feel I’m in a homey, familiar place, despite the fact that the trees and understorey plants are completely alien and there are things scuttling about on the forest floor here that I’m sure I’d rather not know about. Trees are lovely things no matter what part of the world they inhabit and the tropical forest here is wonderfully diverse in a way the solid stands of conifers in my old stomping ground are not. Each time I go to the mountains here I come away with a sense of having missed some of the best bits. That feeling only strengthens my resolve to return again and again, until I manage at last to take in and absorb the full spectrum of loveliness the tropical montane forest offers. I rather like the idea that the task will take a very long time to accomplish since returning to the forest as often as possible is firmly on my agenda, anyway.

Hillside at Bucari, Iloilo

Curiously enough, the exposed rock face of a roadcut I saw on the way to Bucari, a mountain area near Iloilo, sparked memories of mountains in a very different part of the world: Saudi Arabia. Here’s the story. In 2012, during the years I worked in Saudi Arabia, I undertook with a Saudi friend whose family hails from the Hijaz mountains in the western part of the country a two-and-a-half week road trip to see the sights in that region, so extravagantly different from the eastern desert region I inhabited in Dammam on the Gulf Coast. We went at night across the vast stretch of desert that separates the two coasts, at rather a higher speed than the maximum posted, secure in the assumption that the high fences of wire mesh along the road would keep camels from wandering into our path. Camels are the bane of highway travel at night in Saudi, not bad weather. Come up suddenly on a camel standing like a piece of statuary on the freeway at night while you’re hurtling along at 160km per hour and you’ve got a major problem on your hands. (So does the camel, by the way …)

Finally we arrived in Taif, the gateway to the Hijaz mountains stretching away to the south in a long chain all the way to Yemen. We stayed in Taif three days because it was Eid al Fitr (the celebration after Ramadan) and we knew nothing would be open anywhere until the Eid holidays had passed. So, cooling our heels in Taif, we took to exploring the area. It was my first introduction to the mountain landscapes of western Saudi Arabia and I found them enchanting. Not a tree in sight anywhere, mind you — it is, after all, Saudi Arabia, so let’s not get carried away. Nonetheless, there’s more than enough sculptural interest in the land formations and the peaks themselves to satisfy someone like myself thirsting after the experience of mountains, real mountains.

Once Eid was over we hit the road going south, driving eventually all the way to Khamis Mushait just east of Abha, which was our turnaround point for the trip back north. We travelled at leisure and I asked for stops whenever we came across a dramatic panorama or some interesting thing along the road. For my friend I expect it was all rather ho-hum, he’d seen it many times before on family holidays to the area from his home in Eastern Province. For me, it was the first time I saw a portion of Saudi Arabia not only with real mountains but with tangible history, because the history of the country is visible only in the West, not in the desert East where there was nothing but Bedouin encampments until oil was discovered in the 1930’s. In the West, for example, you find ancient rock walls dividing the landscape into tillable fields, for lo and behold, things grow in this part of the country. The old houses are reminiscent of those in Yemen, with decorative stone work around the cornices. There are old things about, seriously old things, that one never sees in Eastern Province.

Traditional Hijazi Architecture

There are ancient watchtowers on the hilltops and ancient villages tucked into the pockets of mountainsides that cascade down precipitously from the highlands to the Coastal Plain, the Tihama. Along the length and breadth of the mountain range I found sights, both natural and historical, of great interest at every turn. The same is true of the natural environment here in PH in the mountains of Panay and Negros, but the interest is of a completely different character. When I saw that hillside of exposed rock near Bucari, I thought fondly of those bare peaks in Saudi Arabia I had seen, so very different but equally beautiful in their own way.

I can think of no better way to recount the experience than to take you with me down memory lane as I look at some of my photos from the trip. Seeing them brings it all back to me as if it were last week that I’d travelled there rather than six years ago. Let’s begin with Taif, where the sightseeing first got seriously underway.

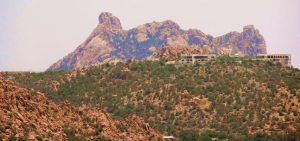

Taif Peak, Saudi Arabia

I should by right say the area around Taif, because Taif itself is …. ummm … problematic. It has a dodgy reputation even in Saudi, where it’s thought to be something like a Wild West town in the cowboy days, but the cowboys are rough and ready Bedouins from the desert tribes to the East. The cowboy simile is not without foundation, to be honest. We came across groups of men when we were out and about who looked like old photos from the 1940’s of Bedouins straight in from the desert, their leathery faces poking out from beneath their wrapped head coverings, looking as if they’d just finished a raid brandishing sawed off shotguns. And the way people drove in Taif was worthy of a full-on rodeo. Yeehaw!! Ride ’em cowboy!! It’s the only time in my life a vehicle as innocuous as a Toyota subcompact has induced abject terror in me. But it’s all good for the memoirs and I live to tell the tale. I did find shocking the trash everywhere on the loose in the city, blowing in huge great waves in the downtown as the wind lifted it and whipped it along the streets tossing it into the trees dotted here and there in the cityscape … it was everywhere. I’d never seen that degree of civic negligence in Saudi before, where it’s easy and cheap enough to have a squad of Bangladeshis tidy up your streets for you if you can’t be bothered to do it yourself (and what Saudi could possibly be bothered?).

Litter in Taif

The phenomenon remains for me inexplicable. I’m happy to report that only in Taif did I encounter it. Everywhere else we visited over the course of the journey showed careful attention to keeping the town in good order.

To the North of Taif is the edge of a great escarpment with a road engineered by some clever Swiss or German chaps (Alpen folk, in any case, I can’t remember from which country) with divided double lanes all the way down the tortuous face of the mountainside. One would expect nothing less from men who had pushed freeways through the Alps, I suppose. We went down it to the bottom, but from that point you either go on to Jeddah, which I had no desire to do, or to Mecca, which my status as an unbeliever prohibits me from doing. Only Muslims may go to Mecca, not heathens like Yours Truly.

Taif Escarpment Highway

There’s a checkpoint on the road to Mecca at which your religious credentials decide whether you go forward to the Holy City or turn back lest the heathen detritus that you are should sully the place. Well, I look about as Muslim as Candace Bergen and had “Christian” on my residency permit card (pure fiction, if the truth be told), so I wasn’t the least bit interested in pushing my luck on the Mecca road. Consequently, back we went to Taif and headed south as soon as the Eid holidays came to an end.

It takes very little time driving south from Taif to hit fantastical mountain landscapes. The stretch between Taif and Al Baha provides a dramatic introduction to what lies ahead through isolated peaks that suddenly loom out when you come round a turn in the road. It reminds one of Arizona, in a way, but I must say that Arizona was the last thing in my mind when I saw these peaks because the feeling of the territory is so wholly different. The American West has no sense of a past vastly different from the present and still immediate in the physical remains of an earlier civilization — the stone walls, the old houses on the hillsides, the ancient watchtowers still standing on the tops of some of the hills despite being unused for centuries now.

Peak near Taif

So the impression the landscape makes as a totality is unique, like nothing I had seen before. In my experience each region of the Earth has its own character, which imparts a particular character to the human life that goes on there. I call this character “feeling tone” because it seems to me closest to music, something one can’t possibly capture in words, just as the emotion or feeling conveyed by a piece of music can only clumsily be rendered into a verbal description but never captured completely. It has no exact verbal equivalent, there’s a complete incommensurability of discourse between that musical reality and the universe of meaning words are equipped to convey. So it is with a landscape. It has a reality one senses easily enough through experience, but it’s impossible to sum it up in words. It’s a felt thing, like music, and lingers in the mind and feeling like music.

So I’d call the stretch between Taif and Al Baha symphonic. It’s cast in broad strokes and contains a variety of themes welded into a unity, as the themes and counterthemes of a symphony are joined together. The contrasts are acute, moving between flat land and soaring peaks jutting up out of nothingness, between the naked granite of the mountainsides and the earthy color of the soil that promises the nurture of some kind of life, a life that on the mountainsides is impossible. Nothing can survive on those bare slopes of granite. So the horizontal and the vertical, the grey and the brown are played off each other but at the same time woven together into a texture that wouldn’t bear the pattern of contrast it shows were either element absent. It’s easy to see why the people who live there love both those elements, for home is made of both together, not of one or the other separately.

With arrival in Al Baha one is back quite squarely in modern Saudi civilization. There are fast food restaurants and teenagers driving around in old Chevrolet sedans, leaning out the windows at the sight of a white tourist to yell, “Hello, welcome to our city!” When we stopped for lunch at a KFC on the main highway, a group of teenage boys charged up to me and each shook my hand in turn while offering the warmest greetings and asking my nationality.

View of Al Baha

It was all quite charming and I did my best to convey with equal warmth my pleasure at the hearty welcome. Nothing of the sort had ever happened to me in Damman, Riyadh or Jeddah. White people are not a common occurrence in Al Baha, nor at any point we reached further south. Similarly, there’s something of the old way of Arab culture in these mountain areas, something softer and more amenable to approach than the institutionalized and regulated life one finds in the major cities, Riyadh in particular. I saw far fewer women’s faces fully covered in Al Baha than in Dammam. A much greater sense of ease spread from the life going on around us. Everything seemed organic, native to the soil of the place, in a way I’d never experienced in the big cities. It may have been due in part to my being a tourist, but I had by this time three years of experience living in Saudi Arabia and I don’t believe I was just easily taken in by the whitewash of tourist experience in an unfamiliar area.

Wildflower, Al Baha

I knew what to look for, mindful of all those subtle things that add up to convey a clear sense of a particular place. The picture that came into focus from the elements I observed in Al Baha was like an Impressionist image compared to a work of Modern Realism. There were soft edges, pastels, bright splashes of color here and there in surprising places, and everywhere I found an abiding sense of people being at their ease, which is never the case in the big cities, quite apart from the urban bustle that goes on there. This was an agrarian society, used to living close to the land and softened rather than hardened by that contact. All around towered the granite mountains, but in the valleys where life took place things were relaxed and unhurried, not tense with the anticipation of hardship or concern about the infraction of a rigid social code. If that awareness of ampleness and ease were the only memory I had taken away from the entire journey, I’d count it full recompense for the time spent traversing the terrain. There was, however, much more to come.

A special trip from Al Baha took us down from the highlands to the coastal plains of the Tihama and to Dhi Ayn (or Dhee Ayn, depending on how you choose to transliterate Arabic), called the “Marble Village” because it sits on an outcropping of white quartz. The experience of going through that amazing abandoned village is worth a separate post, so stay tuned, it’s in the works.

The town of Beljurushi lies a short distance south of Al Baha and is the family seat of the friend with whom I travelled. In Saudi you’re defined by where your family comes from, because family names are tribal and associated with a particular area of the country where that tribe holds forth. So if you are, for example, an Al Dossary, you come from Eastern Province. An Al Quraishi comes from the Mecca area as rule. My friend was born and raised in Dammam in Eastern Province, but if you ask him where he comes from he will answer “Baha” because that’s where his tribe has its seat. His family name is a dead giveaway, of course — a Saudi hears it and immediately thinks, “Baha.” When he visits his relatives in Beljurushi they give him a hard time about sounding like a foreigner, because he speaks Arabic with the inflections of Dammam, not of the Hijaz region. All the same, he’ll insist implacably that he’s from Baha, not Dammam, to the complete surprise of a Westerner like me. I’d never in a million years tell people I come from Ontario because my grandparents hailed from there. In Saudi Arabia it’s the only answer that would be judged accurate.

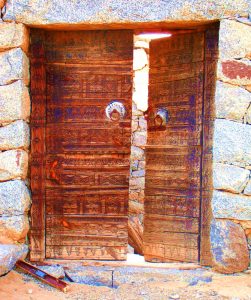

Traditional Carved Door, Beljurushi

It wasn’t our goal to visit the many aunts and uncles and cousins who live in a particular area of Beljurushi that forms its own village. We just drove through on the sly, my friend pointing out which uncle or aunt lives in which house. Then we came to his grandmother’s house, no longer inhabited since her death many years ago but by far the most interesting house of all since it’s in traditional style with a wonderful carved door at the front. I asked my friend to share some of the memories he had of being in the house as a child. What I heard confirmed to me that an older and gentler style of life was dominant in the country before the modern era, a way of life I would have found very agreeable. Even though I received my impression of it only through stories related to me by my friend, whenever I think of that area I think also of that older, traditional way life, not how it is now, with most of the young people off in Riyadh or Jeddah making money as businessmen and returning only a few weeks a year to village houses they’ve built as vacation homes. The climate has changed and the agricultural life that sustained the village has ended because the water is gone. My friend related memories of vegetable gardens and melon fields that used to grow in the vicinity. All that is now a memory, nothing more.

Arid field, Beljurushi

The landscape in its present manifestation speaks only of desert anxious to happen. Whatever life the land sustains is given only a miserly portion of water with which to eek out its existence. Our last stop in the village was the house of an elderly uncle who once had pomegranate trees in an adjacent field. Since the water has gone, they can no longer survive there. In this case the phrase “the good old days” has no irony about it, only the sting of truth.

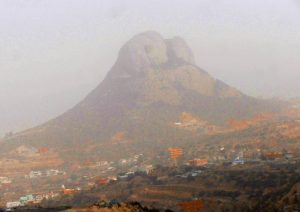

Heading south from Beljurushi one enters a wild area of mountains with very few villages along the way. The contours of the landscape careen this way and that, rise sheer and plunge precipitously, and every turn on the road brings into view a different vista with a different point of perspective. My friend categorically refused to let me share the driving along this stretch of road. I smirked in the passenger seat, thinking to myself that I, bumbling Westerner that I may be, had nevertheless managed to traverse the Rocky Mountains in the dead of winter, so perhaps I’m not quite as hapless as I look. All to the good, though — I was content to let him do the driving so I could devote my attention to the landscape. As misfortune would have it, just as we left Taif a dust cloud from the African plains drifted across the Red Sea to settle over southwestern Saudi Arabia, making the air hazy so that things at distance looked like photographs taken with a fuzz filter. Nonetheless, the sights were fantastic and even the blur did nothing to dim my interest. Occasionally round a bend there came into sight a place of relative flatness where people in the past had thought fit to build a village.

Deserted Village, Hijaz Mountains

More recent generations had obviously thought better of the idea and abandoned the place utterly, leaving the stone houses to stand as a testament to the life that had once happened there and happened no more. The climate works very little damage on the old stone houses so their abandonment looks surprising, as if the inhabitants had suddenly decided to decamp en masse and charged out in a rush leaving everything as it stood. In fact, such villages have been empty for a long time because of the change in climate and rain patterns over the past 100 years. It must have made perfect sense to settle in such a place when the village was founded. Seeing it today in its isolation and aridity, the wisdom of those who exited stage left was equally apparent.

Al Namas … that name still makes me wistful, because it’s my favorite place in Saudi Arabia. After seeing it and staying there for a few days to take in the sightsa, I knew beyond doubt that if someone put to me the question, “Where in Saudi Arabia would you most like to live?” the answer would trip without hesitation off my tongue: Al Namas.

Public Park in Al Namas

The town is not large and lies on each side of the highway much like a small American town in the West does. After just a short westward jaunt from the downtown, however, major drama overtakes the landscape. On what looks like a road that will peter out into bare countryside, all of a sudden there appears a park hugging the edge of the upland plateau. The plateau spills abruptly over the edge into the chasms of the Hijaz as they fall away to the Tihama, the coastal plain. I sat for a very long time just looking at the spectacle before me. Since the mountains are bare of all vegetation, every sculptural feature they have is exposed to full view. If we were to reach for another musical analogy, the term would be fugue. Hundreds of textural elements knit themselves together into a complex and fantastical landscape, the like of which I had never before seen.

Switchback Road to Tihama, Al Namas

I saw two-lane roads twisting down the sides of steep slopes that promised a case of vertigo Dramamine couldn’t hope to handle. My friend threatened to drive down one of those serpentine rides from Hell as we left the park, so I spoke as I found: “Fine, I’ll jump from the car at speed if I have to, suit yourself.” Better a few scrapes than a plummet down the mountainside, right?

But not a mile from this spectacle of sheer dropoffs and immense vistas lost in haze I was astonished to find fruit trees sporting pears. Yes, you read correctly. PEARS. IN SAUDI ARABIA.

Fruit trees in Al Namas

Right there in front of God and everybody, clearly nearing ripeness into the bargain, and — unfortunately — within relatively easy reach over a low stone wall. Is it any wonder I said to my friend, “Don’t stop the car or I’ll do something that will get us into BIG trouble. Just keep driving.” And on we drove. Lead me not into temptation …

Al Meger Museum, Al Namas

Al Namas held one more major surprise in store for me: the Al Meger Tourist Village. The story behind this astonishing institution hinges on the life of one man, named of course Al Meger, who after retiring from a high-level government job bought an empty palace built earlier in the 20th century and began filling it with an incredible array of Saudi heritage items. The collection is displayed with proper museum panache in glass cases and includes the largest and most diverse historical heritage collection I ever saw in the country. Mr. Al Meger received no support from the Tourism Ministry despite repeated appeals and there was no publicity campaign to generate broader awareness of the collection’s riches. In addition to a very impressive museum installed over the multiple floors of the palace, Mr. Al Meger had built adjacent to the museum a full-on hotel complex. It was amazing to see all this development done through the will and application of one retiree.

Interior, Al Meger Museum, Al Namas

I trumpeted the news in every possible direction when I returned to Eastern Province, did my best to have the potential of the place recognized and tapped some cultural officers on the shoulder in the organization where I worked to get them to do something. It was all to no avail. The officers wanted bling, not heritage artefacts — the Mona Lisa on loan, perhaps, not some old plough from a Hijazi village, OMG bore me to death why don’t you. I feel fortunate that I saw the collection when I did, because I doubt it will long survive the death of Mr. Al Meger. The Saudis apparently have no interest in artefacts from their own history. What an enormous pity …

I had no desire to leave Al Namas. I would gladly have spent the rest of the vacation there taking in the beauties of the area and exploring all the nooks and crannies it offers. We had an agenda, however, and that agenda was a road trip, so after a few days in Al Namas we took to the road once again. I was compensated in part — but only in part — by the sight of the region that came next as we headed south: Tenomah.

Valley near Tenomah

Jagged peaks, Tenomah

The approach to Tenomah brings a closer encounter with the kind of landscape one meets just south of Taif. The fact that the encounter is closer makes all the difference, because the walls of bare granite loom over you like crushing weights about to fall rather than being picturesque and sculptural from great distance. If you wanted music to accompany these peaks, I would suggest “Night on Bald Mountain” by Mussorgsky. There’s something mildly alarming in the granite masses when close up or grinning behind a building like the jagged teeth of a jack-o-lantern. At first sight they seemed overwhelming. But as we spent the day going around the mountainous area off the main highway, I began to understand how if one lived with these peaks they could become comforting, like some kindly, giant uncle who looks out for the kids. They’re a bulwark of solidity and extremely slow to change, being of a very hard granite indeed. Up in the foothills of these peaks, in an area so arid only a bit of scrub could survive in a crevice here or there that collected some bit of moisture, I came across a wonder: a garden!

Garden, Tenomah

Down a windy little road leading through the boulders and the scrub we went, expecting to find a dead end with, we hoped, some kind of turnaround. Instead what we found was someone’s house tucked away in a mild declivity with absolutely no visible source of water nearby. An old woman sat on a veranda, her head uncovered, and our approach in the car caused her not a moment’s concern. She was shelling beans, so it seemed, and continued with her task unperturbed. We did indeed find a turnaround near the house, but beside the turnaround was a vision of greenness and fertility I’d never have predicted in that landscape in a million years. There was an apple tree, with apples on it, working their way slowly to ripeness in the warm sunshine. And there were vegetables, some kind of squash growing with plump, fleshy leaves in the middle of a landscape that showed the hardness and bleakness of naked granite at every turn. It was a vision as close to the Muslim idea of paradise as could be: water, greenness, life, ease, coolness, the sustenance of life with the fruits of the Earth. I’ve never forgotten the sight and never will. It remains a keystone in my understanding of my own relationship to the Planet.

OMG Dream Whip!! Abha

And so, finally, almost tearfully, it was on the road again to Abha and Khamis Mushait. Abha is a big city with a big city feel, although Saudis consider it a sort of summer playground because of the cooler climate due to its locations in the mountains. It’s not an amusement park, however, it’s a full-on city with city traffic and malls and … OMG wait for it … We went into a supermarket to get some snacks for the road and as I walked down one isle toward the fruit section, lo and behold, there it was. Dream Whip. Yes, Bridget, DREAM WHIP. I stopped dead in my tracks while trying to take in the sight and stood there so long my friend came back to find me. He looked at me and said, “What on earth is wrong?” It took me a moment to reply. I just pointed at the shelf and said nothing until I found my tongue again. Then I said, “We’re in the boondocks of Saudi Arabia and I’m staring at an American product my grandmother used regularly to make her appalling church basement desserts. That’s what’s wrong.” Cognitive dissonance doesn’t begin to describe it. Shall we find another musical analogy? How about: the final act of Wozzeck by Alban Berg. Something that sounds like the world is busy tearing itself apart. That’s the ticket. The trauma has remained with me to this day and erupts afresh whenever I see the picture I took. In my own mind I kept repeating as I stood there, “Das gibt’s doch nicht.” English: that just can’t be. And yet there it was, as incontrovertible as weather. Draw your own conclusions. Does all seem quite well with the world when Dream Whip hits the wilds of Saudi Arabia? One can only wring one’s hands in wonder …

Abha and Khamis Mushait returned me to the modern urban environment I knew only too well from Eastern Province, since it was cut from exactly the same recent cloth. All very nice, isn’t it, to have malls with Levis and Hush Puppies, bad Chinese restaurants that cover everything in thick brown sauce, and L’Oreal products gracing the personal care section. In fact, one might as well be in Dubuque, Iowa, not to put too fine a point on it. So a few days going about Abha and Khamis Mushait sufficed to bring my romantic wanderings through the Hijaz Mountains to an abrupt end. On the way back I looked at things with a different eye, knowing that I was returning to vast tracts of flat, shifting sand and would have mountains before only my inner eye for months to come. We did one more short stay in Al Namas, because I couldn’t bear the thought of not doing it, and my memories from those few days are among the best I have of my time in Saudi Arabia. Namas is the only place in Saudi that felt to me like home. As I said, it’s the only place in Saudi Arabia that I’d choose to live in, were it a question of choosing one place of residence over another in the Kingdom.

Hamadryas baboons, Al Baha

Back to Al Baha it was then, next in the order of travel, this time with a sidetrip to a mountain area where Hamadryas baboons have largely taken over the park area. I teased my friend unmercifully about them being cousins of his, since his family is from the area — how could I resist? But not to worry, he did payback with compound interest later 🙂

We were to bring pomegranates from Al Baha to my friend’s mother, so we shopped in the public market for a fine box of them to take home. Ah, Arabia — the scent of burning oud rising from a censer in the corner of the majlis (the formal sitting room) and delicious treats made bright red inside with the seeds of pomegranates. There’s so much to appreciate in Arabic culture and cuisine, I feel fortunate to have had the experience of it as intensely and as intimately as I did during my five years in Saudi Arabia.

And thus we ended our travels and once again sped across the wide expanse of desert separating the Hijaz from Dammam, which sits squarely in its desert on the shore of the Gulf, a body of water I’ve never seen resemble anything other than a very large puddle left after a heavy rain. Ocean it is not, not under any conceivable stretch of the imagination. It barely laps the shore and can only be stirred to energetic motion if a strong wind pushes things to that state. It returns to its aquatic catatonia as soon as the wind dies down. I’m tempted to lift from Rebecca West a quip she once made about the Adriatic’s appearance one winter’s day as she approached it by train from Zagreb, when it resembled nothing so much as “one of the bleaker Scottish lochs.” Ditto for the Gulf. No matter the season.

As soon as we were home in Dammam it was back to the routine of work every day, navigating one’s way through the corporate miasma of a large company, running a household and finding ways to amuse oneself to repair some of the damages of the days’ living.

The mountains of the Hijaz stayed with me, however. Despite the fact that I never returned before my final departure from Saudi Arabia, they are still with me. And so shall they be evermore.

Al Meger Tourist Village, Al Namas