November 2018

My first visit to Hofuf came early in my sojourn in Saudi Arabia. I got commandeered to assist with a group tour to the city a few months after my arrival in Dhahran in 2010. The trip itself is hardly worth relating, but it gave me an introduction to the Al Hasa region and to Hofuf, its main city. I recognized even at that early stage of experience in the country that Hofuf is very different from the Arizona-like spread of Dhahran/Khobar/Damman. A sense of being in the real Arabia came over me when I visited Hofuf and I wanted to go back under my own power to explore it in greater detail, without the need to herd a tour group through the souk so they didn’t miss the bus going home.

My subsequent visits to Hofuf were in the company of a Saudi friend who did the driving. I would have been quite happy to help behind the wheel since I had a car and drove regularly in the the Dhahran/Khobar area, but the traffic signs in Hofuf had the atypical and disconcerting characteristic of being entirely in Arabic with no English whatever. In Dhahran/Khobar I could always count on finding English underneath the Arabic on the traffic signs. I’m always up for a challenge, but trying to wend my way through city traffic with undecipherable signage pushed things over the edge even for my practiced sense of adventure. So I let my friend do the driving and just took in the sights.

To give a sense of the difference between Hofuf and the Dammam/Khobar/Dhahran conurbation I should say that the metropolis in which I lived is a very recent phenomenon entirely on the American model. When you drive at night down the main roads in Khobar, it looks like you’re in the States. The most prominent signs are all for American fast food joints. The layout of the streets and the rectilinear outline of the buildings could easily fool you into thinking that you’re in the downtown business district of some place like Albuquerque.

Hofuf, on the other hand, has grown organically over a span of time measured in centuries, having a long history as an area of settlement because of its oasis. The importance of the oasis and the culture that flourished thanks to it can be judged from the fact that in 2018 it became a UNESCO World Heritage Site. From the UNESCO description (website here) comes this bit:

In the eastern Arabian Peninsula, the Al-Ahsa Oasis is a serial property comprising gardens, canals, springs, wells and a drainage lake, as well as historical buildings, urban fabric and archaeological sites. They represent traces of continued human settlement in the Gulf region from the Neolithic to the present, as can be seen from remaining historic fortresses, mosques, wells, canals and other water management systems. With its 2.5 million date palms, it is the largest oasis in the world. Al-Ahsa is also a unique geocultural landscape and an exceptional example of human interaction with the environment.

A testament to the depth of history in the Al-Ahsa region is the Jawatha Mosque, the earliest mosque built in eastern Arabia. From the Wikipedia page (here) comes the story:

It was built in the seventh year of hijra (c. 629 AD) at the hands of the Bani Abd al-Qays tribe which lived there before and early in the Islamic period. This mosque is believed to be the first mosque built in Eastern Province and is where the second Friday congregation prayer in Islam was offered, the first being held in Medina.[3] According to legend, when the Hajr Al Aswad (Black Stone) was stolen from Mecca by the Qarmatians, it was kept in this mosque for nearly 22 years.

There’s nothing else in eastern Saudi Arabia that old. The Dammam/Khobar area grew up as a result of the discovery of oil in the 1930’s and the city as you see it today is entirely new, without any visible history at all, like an American city in the West. Hofuf conveys a very different impression although its history is perhaps not as visible as one might wish. All the same, you can sense it.

The life-giving presence of the oasis makes itself felt through the sight of huge date palm plantations. Hofuf dates are known throughout the country for their high quality. On both trips my friend and I took to the city we went with instructions from his mother to load up on dates before we returned to Khobar. Ramadan was just around the corner when we made the second trip, so we bought a huge box of dates to last through the thirty days of fasting, with all the evening visits requiring Arabic coffee and dates to be passed liberally round to the guests.

I wrote in my post about Bahrain (here) that that in so parched a landscape you can sense the presence of underground water intuitively, as if the body itself were a kind of witching stick. This is what the landscape looks like as you travel between Khobar and Hofuf:

Digging a well in this landscape will clearly get you nowhere, fast. When you reach Hofuf, however, the sight of row upon row of date palms shows that there’s water underground. The body immediately registers the eupeptic sense the water affords and relaxes into the knowledge that life is possible there.

There’s a story to tell about the water in Hofuf, so I’ll draw on information from an article published in 2008 (here):

Al Hassa Oasis with its capital Al Hofuf is the largest oasis in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia and one of the largest spring-fed oases in the world. On an area of about 12,000 hectares mostly date palms were cultivated in former times. The enormous size of the farming area was made possible by the immense volume of groundwater discharging from the underlying aquifers under natural artesian pressure.

In Al Hassa Oasis the groundwater came up from about 280 springs (V IDAL 1951). In the middle of the last century the total spring discharge was about 315 MCM/a (10 m 3 /s). There was a big variation in discharge and some of the springs produced more than 1 m 3 /s (e.g. 1.3 m 3 /s Ayn Haql). Figure 1 shows some historical pictures of the springs. While many of the smaller springs were privately owned, most, including the largest, were linked to a communal irrigation system. The traditional irrigation system was smart and efficient: the water was distributed by gravity flow, and was used several times at different height levels of the oasis. Beyond their use as a basis of Hasawi existence, the springs and pools had an important social value as an amenity for relaxation and hygiene. The sulphurous spring at Ayn Najm, to the west of Al Hofuf, used to be a highly regarded resort.

Together with the adjacent oasis of Al Qatif, the oasis on Tarut Island, and the oasis in Bahrain, the region was settled since the Neolithic period, some 7,000 years ago (see Figure 2). The abundance of fresh water from springs and the strategic location on the crossroads of the trading routes between the Indus Valley, Oman, and Mesopotamia were the basis for the development of the Dilmun culture (5,200 until 2,300 a B.P.), one of the earliest civilizations of mankind (B IBBY 1996). Today the springs are no longer flowing. Due to overexploitation of the groundwater resources the groundwater levels have fallen dramatically and the springs are dried up.

So much for human stewardship of natural resources. We’ve heard that story before, haven’t we … But let’s not dwell on that sorry business, as tourists we’re perfectly justified in putting on our happy face and enjoying the sights without thought for the morrow. Off we go. Let’s get started with some pics:

As one might expect, Hofuf has an old central area surrounded by a lot of new construction that has spread the footprint of the city out over the plain as the march of time moved forward. The central portion isn’t exactly what I’d call “historic,” a better word might be “time-worn.” It’s all good, however, no complaints — in modern Saudi Arabia the car reigns supreme, so it’s unreasonable to imagine twisty lanes plied by donkeys pulling carts. On the first trip to the city with my Saudi friend we stopped in one area near the downtown, obviously a residential area, to ask directions. We found three old gents comfortably lounging near a street corner on a full set of upholstered living room furniture (sofa, loveseat and armchair) arranged on the bare earth beside the sidewalk. Although my friend did the talking and the conversation was entirely in Arabic, I could tell that the gentlemen were as helpful and hospitable as could be. They invited us to take tea with them and lounge on their fine living room suite, but we had places to go and things to see so we declined their kind invitation.

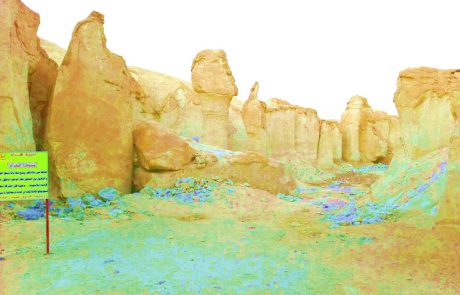

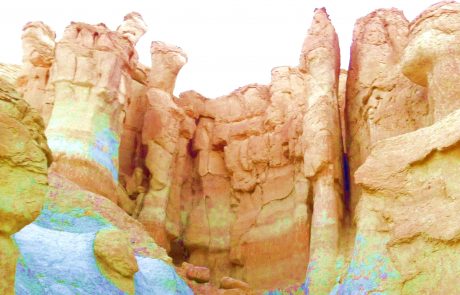

First on the list of sights to see was Jabal Al Qarah (Qarah Mountain, جبل القارة, Wikipedia page here), a sedimentary outcropping weathered into fantastic shapes with several slot canyons. The mountain lies about 10km outside the city and has been set up as a park, albeit the infrastructure is minimalist. It’s a rather lunar landscape, truth be told, and I’m not terribly pitched on spelunking, so a quick tour through the passageways was enough to satisfy my curiosity. There’s a blog post with great photos (better than mine by far) available here. Whenever I took a trip in Saudi I could count on the atmosphere being hazy so that my pictures all look like I had the wrong filter on the camera. Oh well, c’est la vie … That notwithstanding, here are the pics:

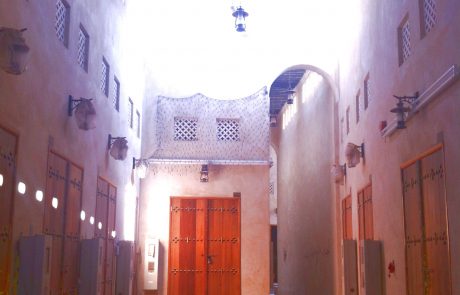

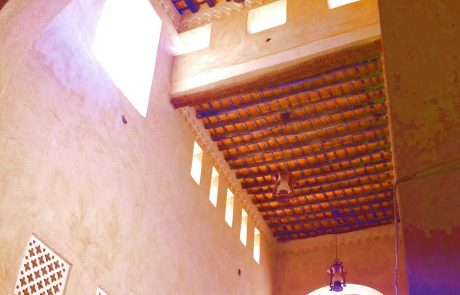

For the history element of the trips the main goal was the Qasr Ibrahim, the Ibrahim Fort, built by the Turks during the dominion of the Ottoman Empire over the area. Hofuf was the administrative center of the Ottomans in the region, so it received a major military building to house the administration. There’s a very good article on it in Saudi Aramco World available here. The original fort dates from the early 16th century, built shortly after the Ottomans took over the area in part to stop the Portuguese from gaining control. They stayed until 1680 when the local Bani Khalid tribe ousted them — without much of a fight, it must be said, and the news probably elicited at the Porte in Istanbul a reaction something like, “Well, whatever.” By that point the Portuguese were long gone and the eastern portion of the Arabian Peninsula probably seemed very small potatoes, indeed. The Fort is the main historical attraction of Hofuf and well worth a look. Here are some pics:

The entrance sign says “palace” but that’s surely giving credit where no credit is due. When one considers the lavish ornamentation of royal buildings in Istanbul in comparison with the starkness of the Qasr Ibrahim, the word “palace” becomes doubly dubious. We’re dealing here with a garrison, a military installation housing a regional administrator and military personnel without any royal pretensions. One imagines the place filled with horses and soldiers doing inelegant, soldierly things, not with courtiers elegantly arrayed and moving at a leisurely place between sites of luxury and repose. It’s a pared-down place for getting business done. There’s nothing unpleasant about the building, but also nothing indigenous. It’s an import, a fabrication on some architectural basis that escapes easy identification but is certainly not Arab in inspiration. So we can enjoy it for what it is, that’s all perfectly fine. For the real Arabia, however, we must go elsewhere: the Souk.

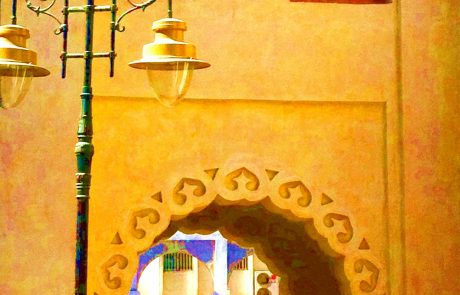

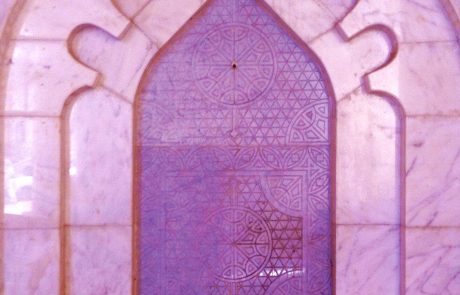

The Qaisariah Souk is within easy walking distance of the Ibrahim Fort. The old building burned down in 2001, unfortunately, so what you see today is a modern reconstruction with some of the decorative elements of the older structure reproduced. As souks go it’s not the huge, chaotic jumble sale one expects of Arab souks — I remember the one in Fez, Morocco, in which I was lost after five minutes and held on for the life of me to the shirt sleeve of the friend I was visiting in order not to get separated from him as we wound our way through the labryinth. The Hofuf souk is all quite manageable in comparison, not very large and laid out with orderly passageways. That’s not to say it lacks charm. The wealth of ornament in the souk and its vicinity charmed me with every visit. Here are the pics:

The geometric inventiveness of Arab artisans never fails to delight my eye. The sampling of motifs you see in the pics above is typical of what Saudi artisans find appealing. The last pic shows my favorite shop — housewares, including the huge cookpots Saudis use for making enormous kabsas (info here), ample enough to feed an entire village. Kabsa is the Saudi national dish of meat and rice, rather like a biryani but not quite so sophisticated as the Mughal taste treat you get in a good Indian restaurant. I loved wandering in the houseware shops looking at all the pots and pans. I never bought anything for my own kitchen since I lived in a townhouse that could have been lifted in toto from some suburb in the American Southwest. My range was American, a 1980’s number with four electric burners, and I’d have been in big trouble had I built a fire on my patio large enough to heat up one of the biggest cookpots on offer at the souk. So I looked and touched, but didn’t buy.

All the examples shown above are of secular ornament. It can be fanciful and free-spirited in a way that religious ornamentation usually is not, especially in Saudi Arabia. When it comes to the matter of religion in Hofuf, we can’t avoid discussing the issue of the Sunni/Shia division in the Kingdom. From the Federal Research Division’s country study on Saudi Arabia (here) comes this information, useful even though the study dates from 1992:

Shia are a minority in Saudi Arabia, probably constituting about 5 percent of the total population, their number being estimated from a low of 200,000 to as many as 400,000. Shia are concentrated primarily in the Eastern Province, where they constituted perhaps 33 percent of the population, being concentrated in the oases of Qatif and Al Ahsa. Saudi Shia belong to the sect of the Twelvers, the same sect to which the Shia of Iran and Bahrain belong. The Twelvers believe that the leadership of the Muslim community rightfully belongs to the descendants of Ali, the son-in-law of the Prophet, through Ali’s son Husayn. There were twelve such rightful rulers, known as Imams, the last of whom, according to the Twelvers, did not die but went into hiding in the ninth century, to return in the fullness of time as the messiah (mahdi) to create the just and perfect Muslim society.

From a theological perspective, relations between the Shia and the Wahhabi Sunnis are inherently strained because the Wahhabis consider the rituals of the Shia to be the epitome of shirk (polytheism; literally “association”), especially the Ashura mourning celebrations, the passion play reenacting Husayn’s death at Karbala, and popular votive rituals carried out at shrines and graves. In the late 1920s, the Ikhwan (Abd al Aziz ibn Abd ar Rahman Al Saud’s fighting force of converted Wahhabi beduin Muslims) were particularly hostile to the Shia and demanded that Abd al Aziz forcibly convert them. In response, Abd al Aziz sent Wahhabi missionaries to the Eastern Province, but he did not carry through with attempts at forced conversion. Government policy has been to allow Shia their own mosques and to exempt Shia from Hanbali inheritance practices. Nevertheless, Shia have been forbidden all but the most modest displays on their principal festivals, which are often occasions of sectarian strife in the gulf region, with its mixed Sunni-Shia populations.

Shia came to occupy the lowest rung of the socioeconomic ladder in the newly formed Saudi state. They were excluded from the upper levels of the civil bureaucracy and rarely recruited by the military or the police; none was recruited by the national guard. The discovery of oil brought them employment, if not much of a share in the contracting and subcontracting wealth that the petroleum industry generated. Shia have formed the bulk of the skilled and semiskilled workers employed by Saudi Aramco. Members of the older generation of Shia were sufficiently content with their lot as Aramco employees not to participate in the labor disturbances of the 1950s and 1960s.

In 1979 Shia opposition to the royal family was encouraged by the example of Ayatollah Sayyid Ruhollah Musavi Khomeini’s revolutionary ideology from Iran and by the Sunni Islamist (sometimes seen as fundamentalist) groups’ attack on the Grand Mosque in Mecca in November. During the months that followed, conservative ulama and Ikhwan groups in the Eastern Province, as well as Shia, began to make their criticisms of government heard. On November 28, 1979, as the Mecca incident continued, the Shia of Qatif and two other towns in the Eastern Province tried to observe Ashura publicly. When the national guard intervened, rioting ensued, resulting in a number of deaths. Two months later, another riot in Al Qatif by Shia was quelled by the national guard, but more deaths occurred. Among the criticisms expressed by Shia were the close ties of the Al Saud with and their dependency on the West, corruption, and deviance from the sharia. The criticisms were similar to those levied by Juhaiman al Utaiba in his pamphlets circulated the year before his seizure of the Grand Mosque. Some Shia were specifically concerned with the economic disparities between Sunnis and Shia, particularly since their population is concentrated in the Eastern Province, which is the source of the oil wealth controlled by the Sunni Al Saud of Najd. During the riots that occurred in the Eastern Province in 1979, demands were raised to halt oil supplies and to redistribute the oil wealth so that the Shia would receive a more equitable share.

After order was restored, there was a massive influx of government assistance to the region. Included were many large projects to upgrade the region’s infrastructure. In the late 1970s, the Al Jubayl project, slated to become one of the region’s largest employers, was headed by a Shia. In 1992, however, there were reports of repression of Shia political activity in the kingdom. An Amnesty International report published in 1990 stated that more than 700 political prisoners had been detained without charge or trial since 1983, and that most of the prisoners were Shia.

I knew people from Qatif and got their side of the story about what it’s like being Shia in KSA. While the people of my acquaintance were for the most part professional and not suffering too badly, it was clear to me that they lived very separately from the Sunni majority and that Qatif and the villages around it were not places a Sunni would think to go unless there was a very good reason to do so. I received invitations to visit people there, but the United States had already placed the area under full travel ban, so that if an American citizen went there and got into trouble the US government would do nothing to help. Consequently, I didn’t go, not wanting to tempt fate. My white face would have stuck out like a sore thumb and the last thing I needed was to be kidnapped by some group needing a useful hostage.

Hofuf is much less tense a place in that regard. To be honest, when I visited I was completely unaware of any noticeable divide between Shia and Sunni communities. Shortly before I left Saudi Arabia, however, there were bombings (laid at the feet of ISIS) at some Shia mosques in Hofuf. The tensions doubtless exist, it’s inconceivable that it should be otherwise given the nature of the beast, but during my visits the issue was not impressed on my attention through things I couldn’t avoid noticing.

In actuality, the Shias have the best bits of Eastern Province — the oases. Qatif is also an oasis region and has farms with vegetables and fruits, something you’ll look long and hard to find anywhere else in the area. The culture of the Shias is different and feels noticeably different to an outsider like me. Shias in Eastern Province are Saudi Arabs, true, but their links are to Shia culture outside the country, predominantly in Iran where the seat of Shia devotion lies. Many of them have Shia relatives in Bahrain, as well, where the Shia population forms the majority although the rulers are Sunni. The links of Shias in Eastern Province with the Shias in Iran and Bahrain are among the main reasons Saudi Shias are treated badly by the majority Sunnis, for whom Iran is anathema and in whose opinion the troubles in Bahrain — occasioned by an uprising of the Shia majority against the Sunni rulers — seem the height of treachery. The conflict between the two groups has gone on for centuries and will doubtless continue well into the future. I educated myself about it but kept well away comment on the political situation. As I’ve mentioned in other posts on Saudi Arabia, the expat’s Golden Rule there is Keep Thy Big Mouth Shut.

If you consider the matter strictly from the viewpoint of aesthetics, however — which of course I do — Shia culture has a vast wealth of architecture, ornament and art worthy of the greatest admiration on its own merits. Think of the Meidan Emam in Isfahan, for example, a UNESCO World Heritage Site (info here), or the Imam Reza Mosque in Mashhad. The link of Saudi Shia culture to the artistic traditions of Iran constitutes for me an enrichment, not a pollution, but I’d certainly not voice that opinion openly in Saudi Arabia except in close company in Qatif or Hofuf.

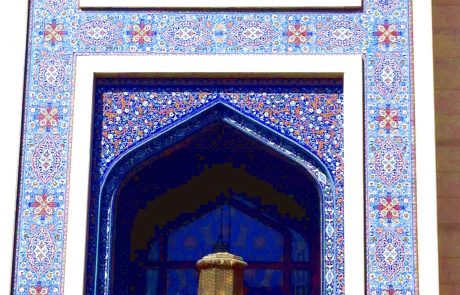

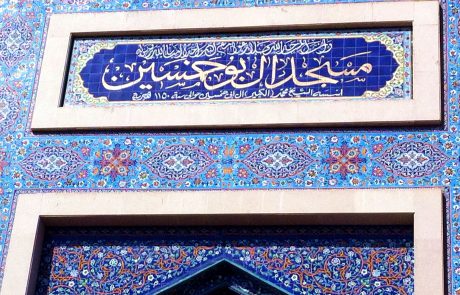

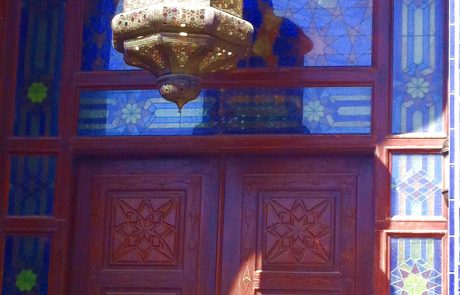

I only photographed one mosque in Hofuf, a lovely building near the Souk. I’m not sure whether it’s Sunni or Shia, to be honest. It doesn’t really matter to me, the aesthetics of the place are the important thing and there’s plenty to like about it whether it’s Wahhabi Sunni or a “Husseynia” as Shia mosques are sometimes called. To the pics:

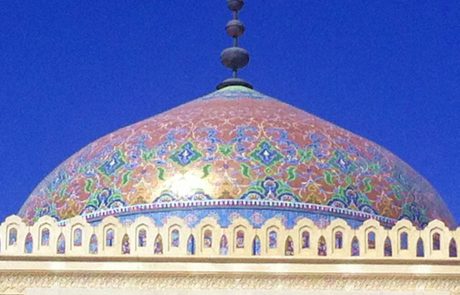

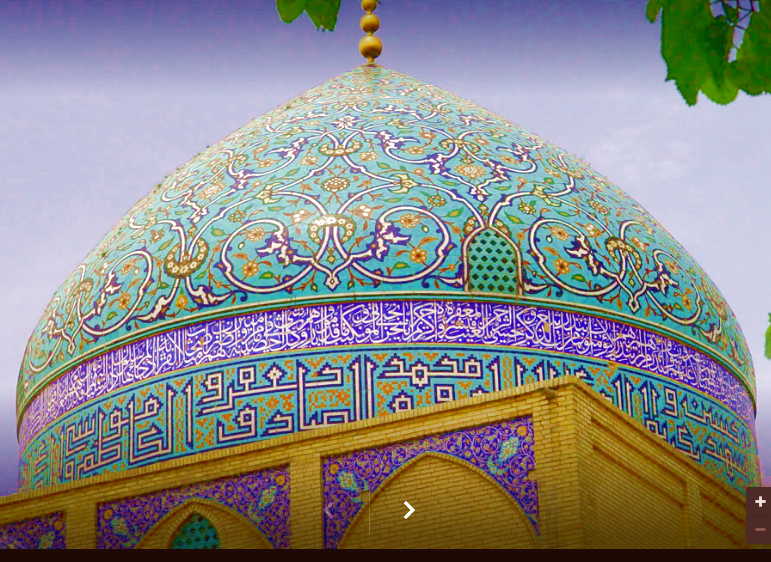

If asked to guess whether this mosque is Sunni or Shia, I would say Shia. Why? Because of the decoration. In my five years in Saudi Arabia I never set foot inside a mosque, being a non-believer (and thus forbidden access to Mecca and Medina), but I saw an enormous number of mosques in my travels throughout the country. The mosque in Hofuf reminds me of nothing I saw elsewhere in Saudi Arabia, it hearkens back to mosques in Iran. Here, for example, is the dome of the Lonban Mosque in Isfahan:

Compare that to the pic of the dome on the Hofuf mosque and the similarity is immediately apparent. One sees similar architectural ornamentation elsewhere in the Muslim world, of course — the fantastic mosque fronts in Samarkand spring immediately to mind. Modern Saudi Sunni mosques, however, are usually pointedly modern in design and plain in their ornamental schemes. They don’t carry on the traditions of Arab religious ornament developed in the broader Muslim world because the Wahhabi Sunnis don’t want to be associated with the history attached to those traditions. Wahhabis feel themselves to be purists set apart from other traditions, a stance reflected in their preference for modern and relatively plain architecture for their mosques. Thank goodness other traditions adopt the stance that ornament should be rich in order to reflect the glory of the Creator. I give that policy a huge thumbs up.

I only learned recently that the Al Ahsa region had become a UNESCO World Heritage Site. I think it’s wonderful the area has received that honor in recognition of its long history among the inhabited regions of the world. My hope is that Hofuf benefits from the designation and finds itself inspired to preserve even more of its traditional ways, which offer as much delight to the visitor as they afford pleasure to those who call the place home.