Stonework, Dhi Ayn, Saudi Arabia

I mentioned in the post about the mountains of Saudi Arabia that a special trip from Al Baha down to the Tihama took me and the friend I travelled with to the so-called “Marble Village”, Dhi Ayn, or Dhee Ayn, choose your spelling because nobody has the final answer when it comes to transliterating Arabic. The village was only on the periphery of my friend’s awareness, not squarely in the travel plan with the double underlining and exclamation points it deserves. To be honest, I think his primary interest in the trip was driving the new — and very fancy — highway going down the escarpment from the highland plateau on which Al Baha sits to the coastal plain known as the Tihama. The road is another of those German engineering tours de force that all that lovely oil money allowed Saudis to buy with their pocket change.

Highway from Baha to Dhi Ayn

The engineering is decidedly impressive. When one considers the roads from earlier times for the trip down to the flatlands along the coast, it becomes obvious that everyone who drives on the new highway should sink to their knees in gratitude before beginning the trip down and repeat the gesture when they reach the bottom. The earlier roads are roughly paved goat trails that regularly see catastrophic accidents and loss of life. My blood ran cold at the sight of them. I wouldn’t dream of taking a bicycle down them, let alone the ramshackle Toyota pickups I saw twisting their way down the mountainside.

Deserted Hilltop Village, Al Baha Province

On the way down there was memorable mountain scenery, to be sure, but also a great conundrum. Looking from the highway about halfway down the route — which is to say, at a good distance from any other settled area in the region — one sees an abandoned village on the rounded top of one of the hills. I asked my friend to stop so I could contemplate the sight because the sight of it was arresting. Why in the name of all that is irrigated and agricultural did a group of people decide to perch their stone houses on that hilltop? Was the desire for an impregnable and secure setting so strong that it overrode all consideration of liveability? How did they grow their food? There were obviously no tilled plots possible in that place. How did they get their water? There’s no running water anywhere in the vicinity, on that account you may rest doubly assured. I wracked my brains for an answer to at least one of the questions that rattled around in my mind as I stared at the ruins, but neither logic nor intuition came to my aid. To this day I’m completely at a loss about both why and how such a settlement came to be. The only thing that makes sense to me is that people no longer live there.

Once you finally wind your way down through the slopes to the Tihama, things don’t exactly go flat right away. I’ve never been all the way across the plains to the sea, so things may get progressively more horizontal the closer one gets to the water. In the area of our Marble Village, however, the vertical is still very much in charge.

View of Dhi Ayn, the Marble Village

The approach to the site provides glimpses of the village until you round the last turn and finally it stands there before you as you go down the road leading to the parking area. It’s an astonishing spectacle in full view from a distance. It should have been used in some part of The Lord of the Rings films, but I fear it would have been cast as the site of some dire goings-on near Mordor, given the bareness of the landscape and its desertedness. The fact that it was abandoned should be taken simply as a fact, not a judgment. Even without inhabitants the village still manages to look rather jaunty on its astonishing perch. However jaunty, though, one can see straightaway there was never a Starbuck’s, and it’s obviously no place for an outlet mall. One suspects that life was challenging here even at the best of times. It’s all wonderfully picturesque, but hills must be walked up and down, and if there’s no plumbing some of that walking up and down must involve carrying water, and if there is to be cooking in the houses people must haul wood or something else to burn, and so on we go until we fabricate a full conception of householding in a surrounding environment that offers easy life only to extremophile microbes. I myself walked up and down, down and up that hill as I inspected the village at close range. I can report from the experience that the inhabitants, who no doubt repeated the exercise many times daily, must have had the leg muscles of finalists in the Tour de France.

Houses in Dhi Ayn

The village wears its abandonment lightly, which is curious because it has been a long while since people lived here. Nevertheless, the structures still have something of the air of being lived in, an impression enhanced by the decorations one comes across as one wanders about the site. I was unprepared for the sight of them, having no idea what Arabs from 400 years ago might do to embellish their houses.

Carved Shutter, Dhi Ayn

Only the architectural decorations remain, of course, but they hint at what must also have been inside the houses, since people who take the time and trouble to carve a lintel with geometric patterns and make of their wooden shutters a field on which to plan and execute a decorative design must surely have had similar embellishments on the articles they used in daily life inside their dwellings.

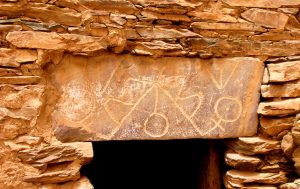

Glyphs at Dhi Ayn

The purely decorative elements were not strange to me because they called to mind other motifs I had seen used in textiles and carvings from the Hijaz region. Over the door of one house, however, appeared a glyph-like decoration I couldn’t interpret at all. I have no idea if the symbols and their arrangement mean something according to some system of symbology used by the villagers, or if what we see is simply the flight of fancy of some inhabitant. Some of the glyph elements look recognizable enough to hazard a possible meaning, but the ice of interpretation is so thin I am bound to go through it on the first attempt. So I’ll leave the curiosity as a curiosity and defer interpretation to someone better qualified than I to deal with historical artefacts from that culture and period. To me it looks like Australian Aboriginal from the pre-historical period, so clearly I’d better leave well enough alone.

Stream at Dhi Ayn

Whatever success the village had over the length of its lifetime depended on a ready source of one thing all human habitations require: water. There’s a year-round stream a short distance from the village that offers a microenvironment as different from that of the hilltop houses as night is from day. The source is somewhere far up in the hills. The stream runs down a channel and spills over a small rock face before continuing its path to the depression at the base of the marble hill, where gardens thrive. Beyond the vicinity of the water course all is grey stone — it’s a mini-Nile, if you will, a band of life and greenness in the middle of a granite desert. There’s a small sitting area where the stream spills over the rocks, in which my friend and I repaired the damages of the morning’s exertions up hill and down dale. It was the only time in five years of living in Saudi Arabia that I felt myself to be in a natural environment where life seemed possible without thinking carefully about how to keep it going.

The presence of the water brought with it a variety of plants both large and small. Right beside the water grew small delicate ferns clinging to the rock face. In the ravine that carried the water to the depression at the base of the hill there were proper trees, put there by no one but Creation and obviously doing quite well, thank you very much. Nothing in that environment beside the stream was artificial. That’s why the spot reminded me of the United States, not of somewhere else in Saudi Arabia. Everything — and I do mean EVERYTHING — in my suburban environment in Dhahran was artificial, down to the trumped up topsoil in which the grass surrounding my building was planted. The lawn survived only through the frequent application of treated grey water used for irrigation. By frequent I mean twice daily. Had the water supply failed for a week, the lawn would have become as dry as a saltine cracker. Moreover, the water that came into our development at the beginning of the use cycle was the product of an enormous desalinization plant down on the Gulf coast in Al Khobar, just 20 minutes away. Water for domestic use throughout central and eastern Saudi Arabia comes primarily from such colossal desalinization plants, not from fossil ground water sources, which were exhausted many years ago.

Stream, Dhi Ayn, Baha Province

The feeling I had sitting beside the stream at Dhi Ayn surprised me because it had been a good while since last I’d felt it: relaxation. Deep ease, taking a deep breath and letting the tension go. We’re all going to heaven and Vandyck is of the company. I said nothing about this feeling to my friend because I knew it was alien to his experience. He’s from Eastern Province, he’s never known what it means to live in active engagement with the natural elements that make life possible. When he turns on the tap at home, water comes out — period, end of story. Where the water comes from is someone else’s concern. Having grown up in the countryside of the American Pacific Northwest on a ranch with its own well, my past reminded me what it is to turn on the tap and know exactly where the water comes from. In our case on the ranch it came from the snowpack on the mountains surrounding the lower meadow, and if the snow was not abundant in any given winter, there could be trouble watering the garden in August.

Sitting beside the stream at Dhi Ayn the country-dweller I was throughout my youth saw the lay of the land, assessed the hydrological situation and relaxed gladly into a feeling of well-being. I realized in that moment that I never felt that sense of relaxation in my artificial environment in Dhahran. I knew instinctively that all the props used to create the illusion of well-watered suburbia were flimflams. The water still tasted mildly of salt when it came from the tap. A few strategic bombings of the Gulf coast would wipe out the water supply for the majority of the population in one fell swoop. That awareness created in me a tension I carried with me every day just beneath the surface of consciousness. It was hardly something one brought up at cocktail parties. “Hahaha, just think if the Iranians bombed the coast, we’d soon be paying more for a bottle of the old H2O than we do for the Jack Daniels from that chap at the Embassy LOL.” No, no, nothing of the sort. Life proceeded as if our water source were an act of God, unassailable and unstoppable. Just turn on the tap and don’t worry that pretty little head of yours. But it was all a lie, of course, and some part of me knew that only too well.

Garden, Dhi Ayn

Beside the falling sweet water at Dhi Ayn I felt for the first time since I had left the United States three years earlier fully connected to Nature. There, in that place, the Earth made the continued existence of a creature like me natively possible, with relatively little to-do involved into the bargain. The water flowed all year long, fed by the rains that come from Africa. From that single fact flowed all the life that had happened there — the gardens, the fodder for the goats and sheep, the soup cooking over the wood fire, in short all the things that constituted the life of this village over the centuries of its existence. The water still flowed. The garden in the depression at the base of the hill was still green. Because there was water here, there was also life.

This kind of oasis environment is of course close to the Arab vision of Paradise. It occurs over and over again, in the Quran, in classical Arabic poetry, as well as in the fountains you find in the courtyards of upscale Arab hotels: water is the Arab’s sine qua non of Paradise.

Mountains near Dhi Ayn

It wasn’t a difficult proposition to accept sitting beside the stream at Dhi Ayn. A cursory glance toward the bare granite hills encircling the village sufficed to point out what occupied the opposite end of the spectrum. I sat by the water for a long time, indeed I had to be pried away by my friend, because I knew that once I left the ambit of that small stream I’d be back in the middle of the Saudi Big Lie, where water is a trickster and leaves a faint trace of salt when it dries on your dishes or on your toothbrush. Dhi Ayn was the Real Deal: fresh water that had come from the skies and gave life with no conditions attached. Paradisical, some might say …

Eventually, before the afternoon wore on too long, it was time to head back up the highway to Al Baha. The sights were different going up the highway, since the eye was not teased out into the long vistas the descent provided. The ascent brought one face to face with the formidable mountains and enhanced even more my respect for the engineers who masterminded the new road. Just the sort of chaps you’d want sorting out your affairs if you’re a Saudi transportation official with pots of money to spend. Nothing but the finest, good sirs, spare no expense, we want the finest highway in the Middle East. Something to rival those things we see on television in Switzerland, that’s what we’re after. And — several hundred million riyals later — poof, there you go, done and dusted.

So ends the tale of my visit to Dhi Ayn. I will never see the place again in my lifetime, I’m sure. The trip through the Hijaz mountains I took is unrepeatable, and knowledge of that fact brought an edge of intensity to the experience. The impressions I recall of my day at Dhi Ayn are indelible. All I need do is close my eyes and think of the stream tumbling over the rock at Dhi Ayn and it all comes back with crystal clarity. I’ll content myself with that image, knowing it comes from the essence of the place, a small piece of paradise in the Arab lands.

Dhi Ayn with Mountains